King Edward I of England Steals the Title “Prince of Wales”, 1301

“Thou great Creator of the world,

Why are not thy red lightnings hurled?

Will not the sea at thy command

Swallow up this guilty land?

Why are we left to mourn in vain

The guardian of our country slain?

No place, no refuge, for us left,

Of homes, of liberty, bereft;

Where shall we flee? to whom complain…”

“The Dirge of Llywelyn”

—By Gruffudd ap yr Ynad Coch (Meaning: Gruffudd Son of the Red Judge, Welsh Bard, late 1200s)

King Edward I of England

Steals the Title “Prince of Wales”,

February 7, 1301

![]() he reign of King Edward I of England was made notable and is recalled for many things. His nicknames—those of “Longshanks” and “Hammer of the Scots”—suggest what an imposing figure he was personally while the chronicles of his time tell us of legendary exploits in the Crusades, his conflicts with the French, and his eventual last days spent at enmity with the Scottish hero William Wallace. Considered by many historians to be one of England’s greatest kings—a bold statement regarding a country that produced so many—Edward I was impressive in a ruthless way: wise but also bold, and undeterred by the impossible. He left his mark on the nation he ruled but also on the nations he crushed, often enshrined in history and song as a tyrant.

he reign of King Edward I of England was made notable and is recalled for many things. His nicknames—those of “Longshanks” and “Hammer of the Scots”—suggest what an imposing figure he was personally while the chronicles of his time tell us of legendary exploits in the Crusades, his conflicts with the French, and his eventual last days spent at enmity with the Scottish hero William Wallace. Considered by many historians to be one of England’s greatest kings—a bold statement regarding a country that produced so many—Edward I was impressive in a ruthless way: wise but also bold, and undeterred by the impossible. He left his mark on the nation he ruled but also on the nations he crushed, often enshrined in history and song as a tyrant.

Edward I (1272-1307)

Talley and the Beacons, Wales

For Wales—one of his more forgotten conquests—the legacy of their subjugation lives on to this day with the stolen title of “Prince of Wales” being passed to incumbent sons in line for the English throne. King Edward I was responsible for this.

Before Edward’s time, the country of Wales—that westward outcrop of Great Britain—was a wild place with a formidable history. It was ruled by various native kings and princes and made up of many separate tribes. Comprised of Briton and Celtic peoples, many of whom had been driven westward by the invasion of the Angles and the Saxons, they had close ties with Ireland and Scotland. They shared attributes with these countries more than with England and predominantly retained their Celtic form of Christianity when the rest of Briton fell back into paganism after the withdrawal of Roman governance in the fifth century.

Celtic village Din Lligwy (pre-Roman) in present-day Anglesey, Wales

When Christianity retook the island of Great Britain, the Welsh could often be found aiding such heroes of the faith as Alfred the Great against the Vikings in the 800s. But this aid was an exception made for fellow Christians to help defeat a barbaric invasion; it did not suggest amiability towards being incorporated into King Alfred’s dream of a unified England.

By the time of the Norman invasion of 1066, Wales had gotten quite comfortable in ruling itself. Divided into four main kingdoms, peace between them was wobbly, yet the Welsh remained self sufficient, formidable and most importantly, distinctly non-English. The Welsh considered their new Norman invaders as “gratuitously cruel” and under the leadership of Irish-born ruler Gruffudd ap Cynan—an erstwhile invader himself—they liberated themselves and were granted autonomy by the Anglo-Norman King Henry II, at the price of paid homage. The following years were filled with infighting and various betrayals. Incursions were made by both Scots and Normans at the invitation of various Welsh princes, and power grabs were common amongst the divided kingdoms. However, any attempt at complete subjugation failed.

Gruffudd ap Cynan (c. 1055 –1137)

Llywelyn ab Iorwerth “The Great” (c. 1173-1240)

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (1223-1282)

The Northern kingdom of Gwynedd was the largest and most powerful in Wales, and a few of their Princes began to use the title “Prince of Wales” starting in the late 12th century, less as an act of defiance against England than a means to assert their supremacy over other Welsh rulers. It was in 1194 that the Welsh became truly united under Prince Llewelyn the Great, who drove the English out and kept them out for the entirety of his reign.

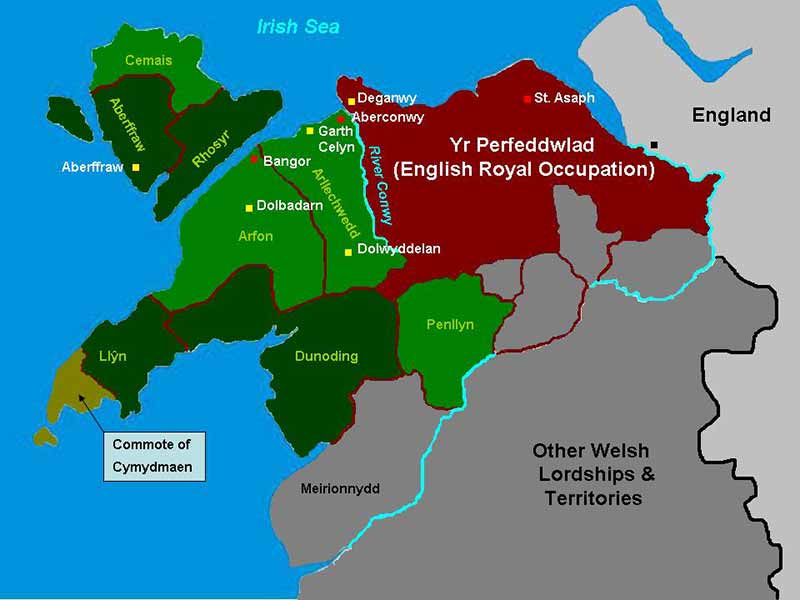

Gwynedd following the division of 1247 at the kingdom’s maximum extent

His grandson, Llewelyn II ap Gruffydd, worked to expand his family’s authority in Wales. He forcefully bound together the southern and western kingdoms, uniting them with his northern one, making the unified principality of Wales a political reality and himself their first acknowledged overlord. His reign was further legitimized when the English King Henry III formally recognized his title and authority as Prince of Wales in the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267.

Map of Wales after the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267

The death of King Henry sounded the death knell for this age of Welsh independence and respectful interrelations. In 1272, Henry’s warrior son, Edward I, ascended to the throne of England and soon made clear he had no intention to honor his father’s treaties.

The Welsh prince and his family had become too powerful, accumulating allies and land in England, not always diplomatically. Following Prince Llewelyn’s inflammatory marriage to a lady of the rebellious Monfort family, King Edward demanded Prince Llewelyn’s homage at court in Chester, offering an exchange of ruling Wales for a position as an English lord. Prince Llewelyn and his brother both refused to give up their birthright. Thus, King Edward instigated his crushing invasion of Wales.

Caernafon Castle, Gwynedd, Wales, where Edward II was born and titled “Prince of Wales”

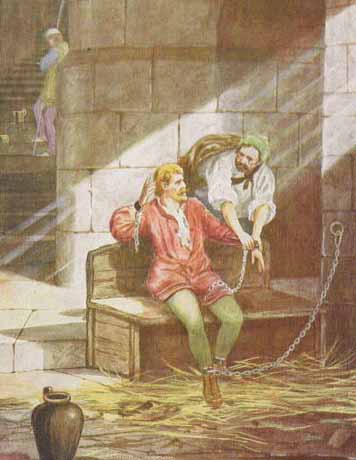

It began in 1277: his armies overwhelmed the poorly equipped Welsh and erected an impregnable line of castles to enforce their occupation. King Edward slew Prince Llewelyn ap Gruffydd and his brother Prince Dafydd, and after their deaths Welsh resistance crumbled. Like any conqueror worth his salt, Edward I had a taste for the theatrical and was keenly aware of the symbolic importance of titles, heraldry and culture to the populace he had subjugated. Just as he took Scotland’s Stone of Destiny back to Westminster as a trophy, Edward’s last crowning touch to his conquest of the Welsh occurred on this day in 1301 when he bestowed the title “Prince of Wales” upon his effeminate son, later King Edward II. Edward II’s own crushing defeat at the hand of Scotland’s King Robert the Bruce thirteen years later at the battle of Bannockburn, and his subsequent overthrow by his own wife, came too late to cheer or liberate the Welsh. Despite various revolts and political movements since, it remains an integral part of the United Kingdom.

Edward I bestowing the title of “Prince of Wales” upon his son, Edward II

England’s Coronation Throne—with a space below for Scotland’s Stone of Scone to be mounted—was commissioned by Edward the I for his coronation as a meaningful statement of Scotland’s subjugation

The title of “Prince of Wales” is now synonymous with British royalty. The position is currently held by Prince William, next in line to the throne. In 1969, King Charles—who himself was Prince of Wales at the time—had his investiture televised with great pomp and symbolic pageantry at the pleasure of the late Queen Elizabeth. He was the 21st heir to the British throne to hold the title. It took place at Caernarfon Castle (birthplace of Edward II, for whom the title was originally stolen) and to the pleasant surprise of his new subjects, Prince Charles addressed the staunchly nationalist crowds in their native Welsh tongue.

A 2019 march for Welsh Independence in Cardiff, Wales

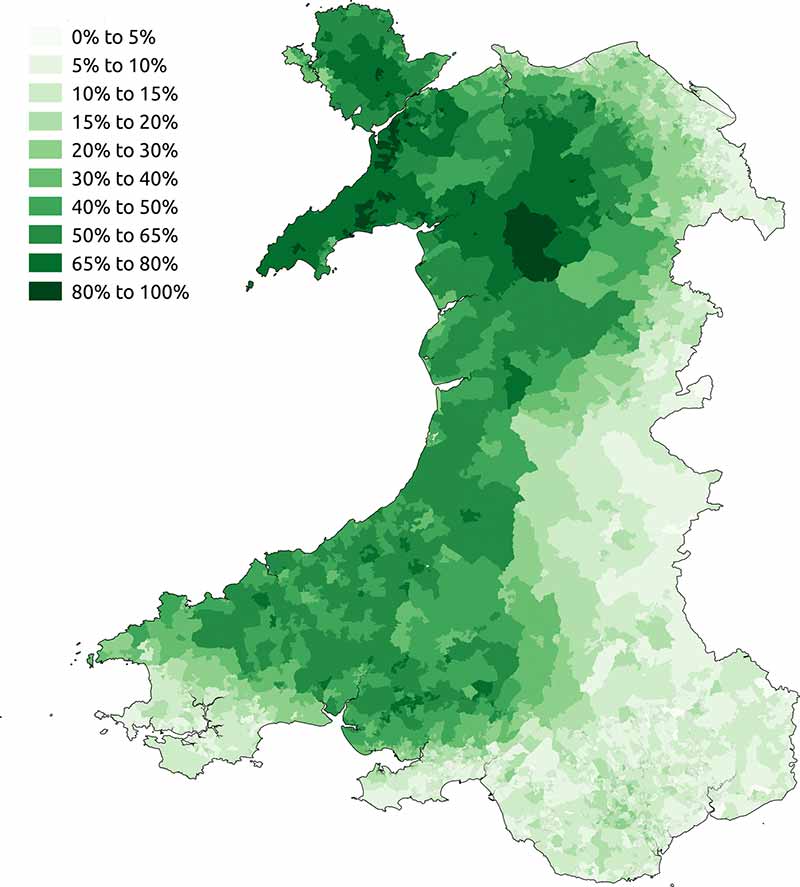

Today the Welsh Nationalist movement is far from dead and has seen many iterations over the generations. The street movement is stronger than ever: September of 2023 saw 10,000 people rallying in support of Welsh independence in the city of Bangor. Like with Ireland’s and Scotland’s own independence movements, however, much of Wales is both influenced and diluted by EU politics. As for the culture, like with Ireland, there has been a resurgence of pride and interest by many in the younger generation—a relief, as even the national language was predicted to be extinguished by the 21st century. According to official statistics, some 880,000 people now speak Welsh in Wales, and the country is well on track to hitting the target of a million speakers by 2030. Younger generations have never known a Wales without Welsh at the forefront, and have a confidence and pride in a language almost unheard a century before.

Population of Wales who speak Welsh, according to the 2011 census

Image Credits: 1 Edward I (wikipedia.org) 2 Talley and the Beacons (wikipedia.org) 3 Celtic Village (wikipedia.org) 4 Gruffydd ap Cynan (wikipedia.org) 5 Kingdom of Gwynedd (wikipedia.org) 6 Treaty of Montgomery (wikipedia.org) 7 Llywelyn The Great (wikipedia.org) 8 Death of Llywelyn (wikipedia.org) 9 Caernafon Castle (wikipedia.org) 10 Edward I & II (wikipedia.org) 11 Coronation Chair (wikipedia.org) 12 Welsh Independence March (wikipedia.org) 13 Percentage of Welsh Speakers (wikipedia.org)

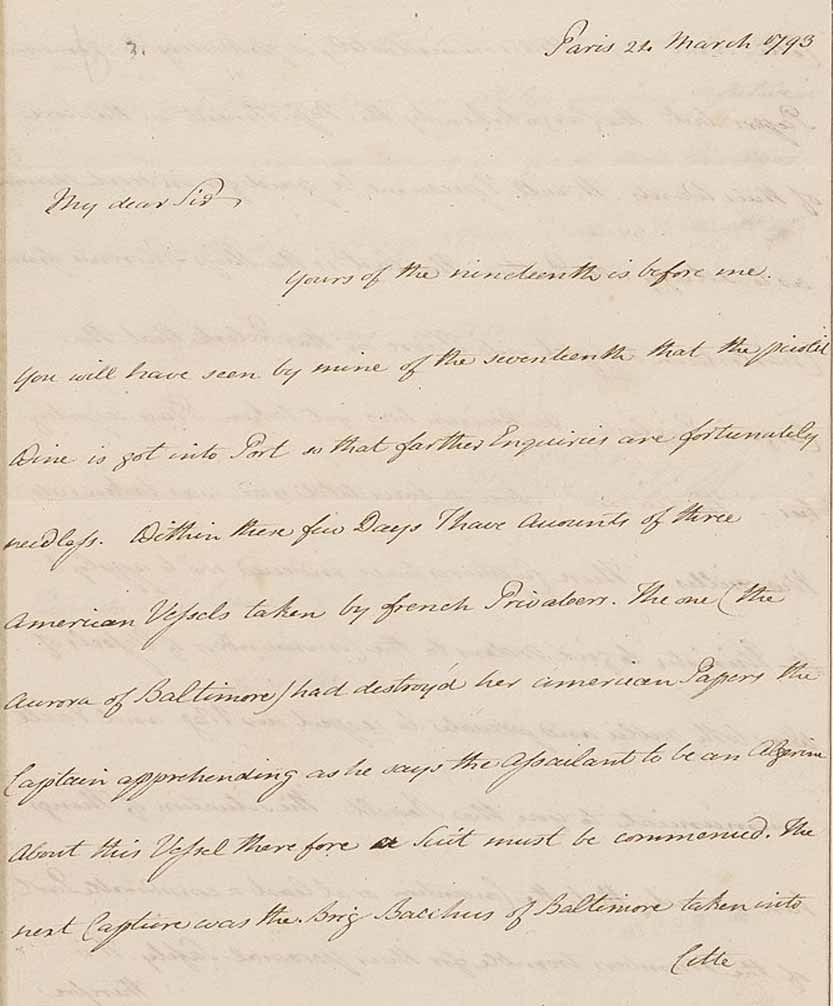

riter of the preamble to our constitution, leading patriot of our revolution, esteemed member of the Continental Congress, wartime minister of the Treasury and American Ambassador—to name only a few of his notable stations—Gouverneur Morris is one of our forgotten founding fathers.

riter of the preamble to our constitution, leading patriot of our revolution, esteemed member of the Continental Congress, wartime minister of the Treasury and American Ambassador—to name only a few of his notable stations—Gouverneur Morris is one of our forgotten founding fathers.

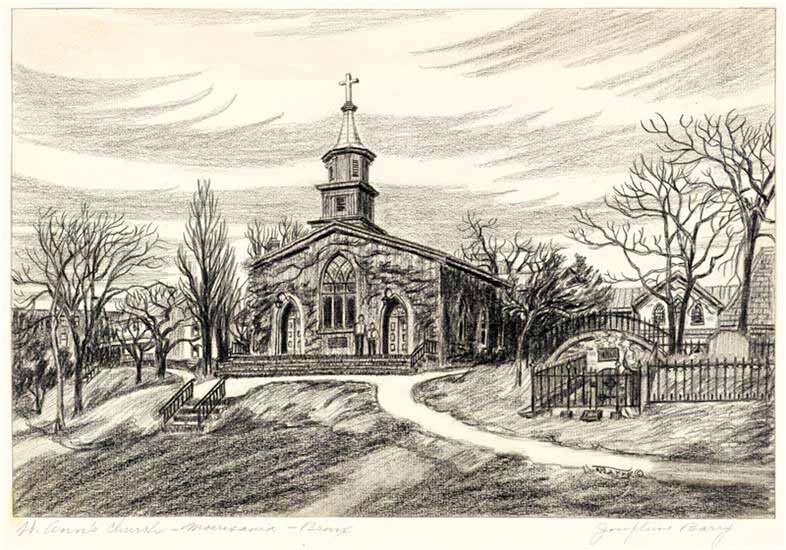

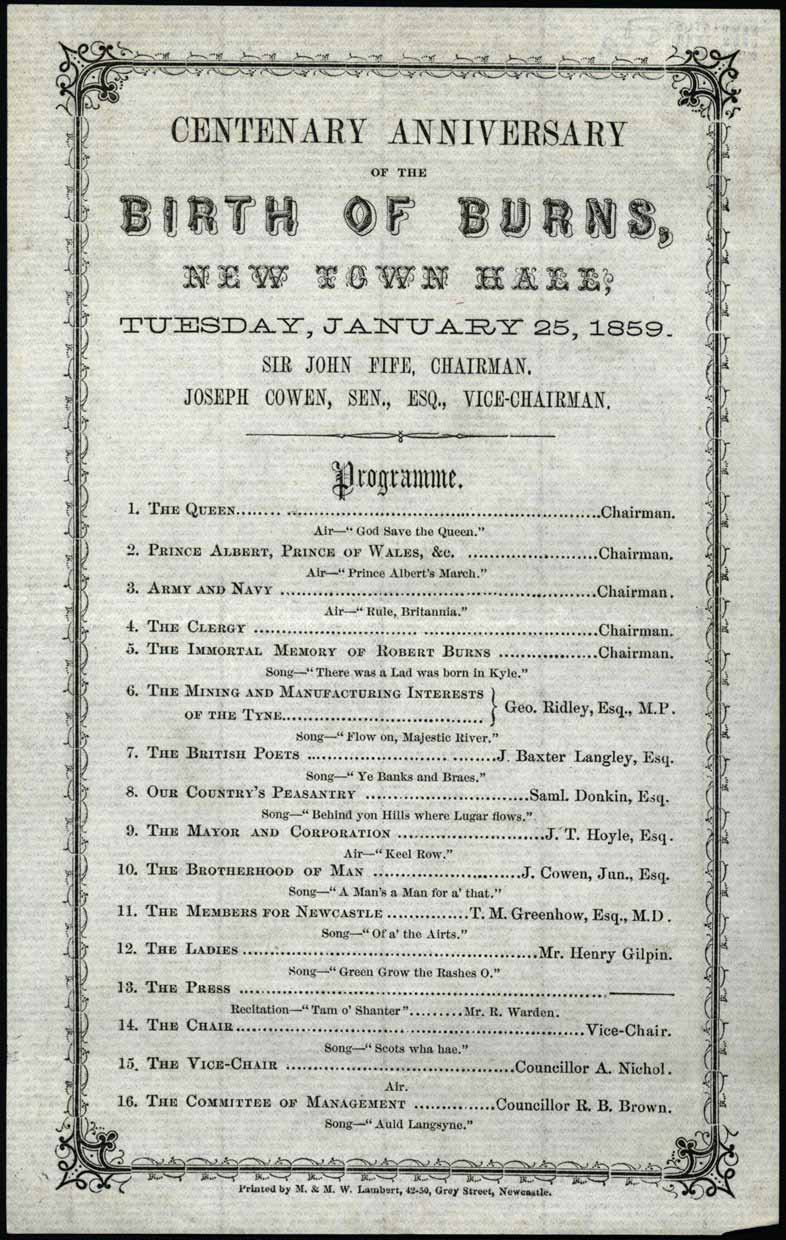

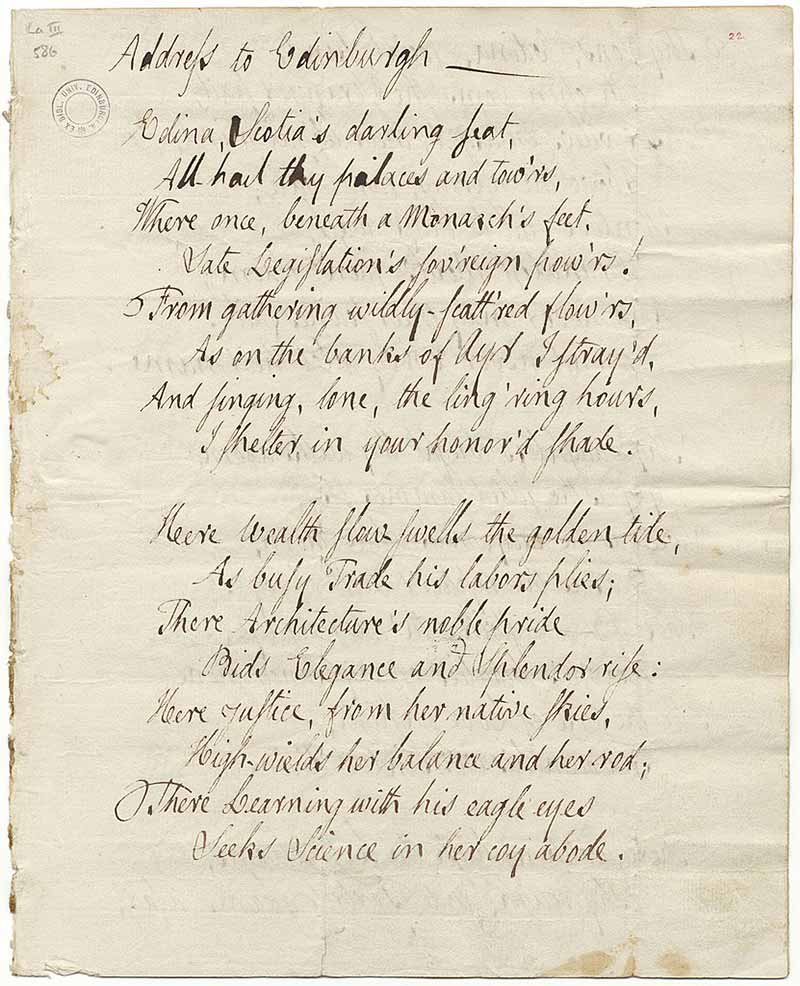

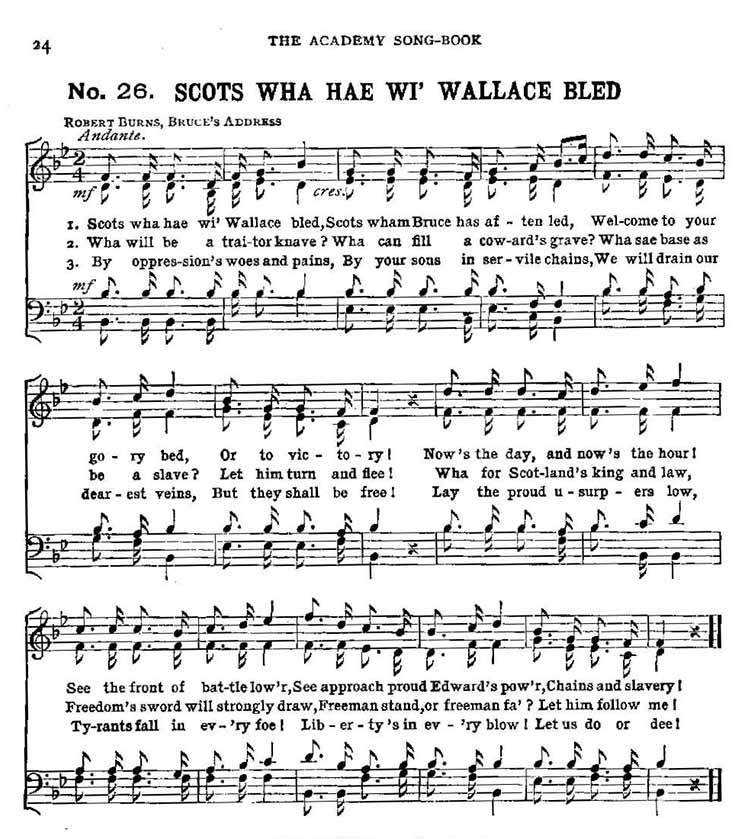

n this date, all over the globe, in royal grandeur and in humbler abodes, “Burns Night” is celebrated. Toasts are drunk, verses recited, odes offered to the famed haggis, and Scotland’s Bard is remembered.

n this date, all over the globe, in royal grandeur and in humbler abodes, “Burns Night” is celebrated. Toasts are drunk, verses recited, odes offered to the famed haggis, and Scotland’s Bard is remembered.

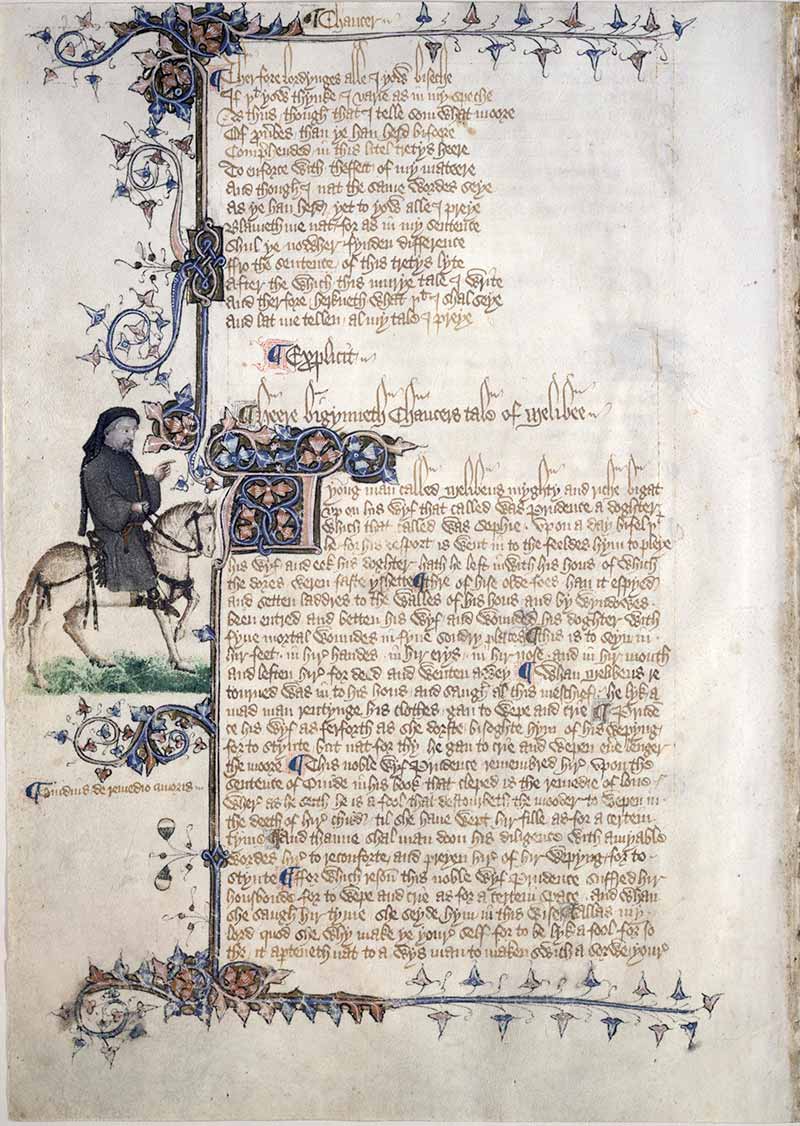

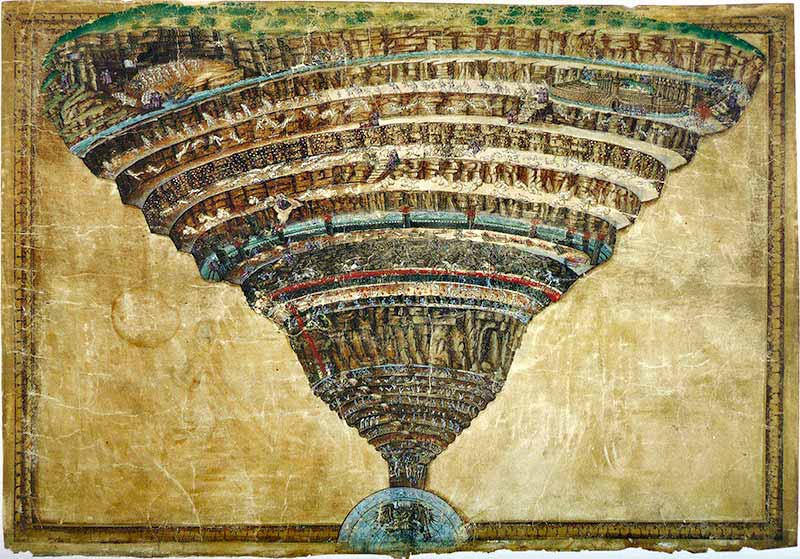

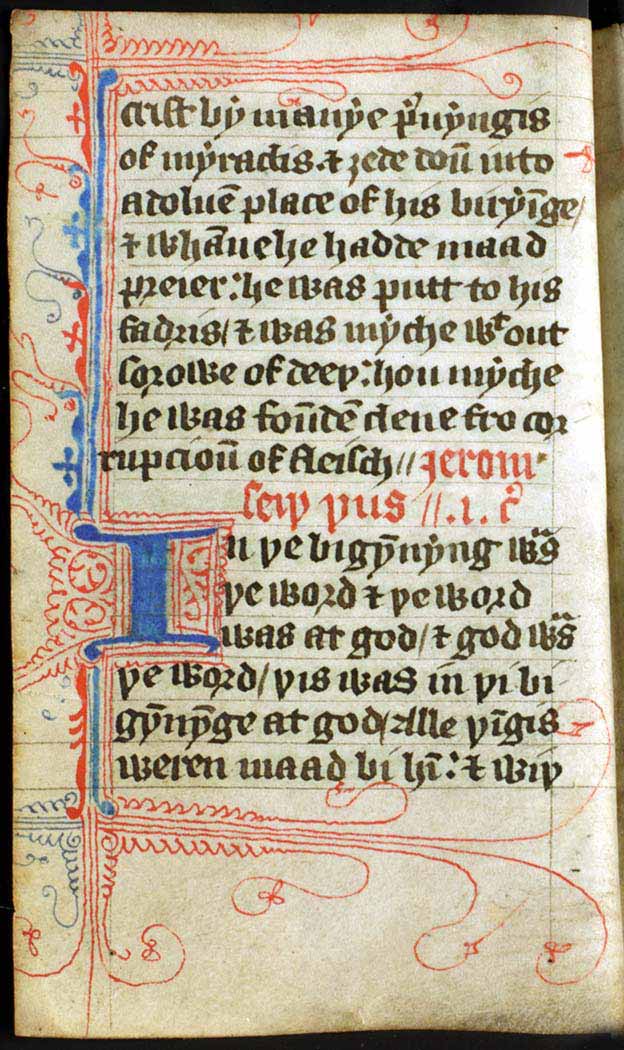

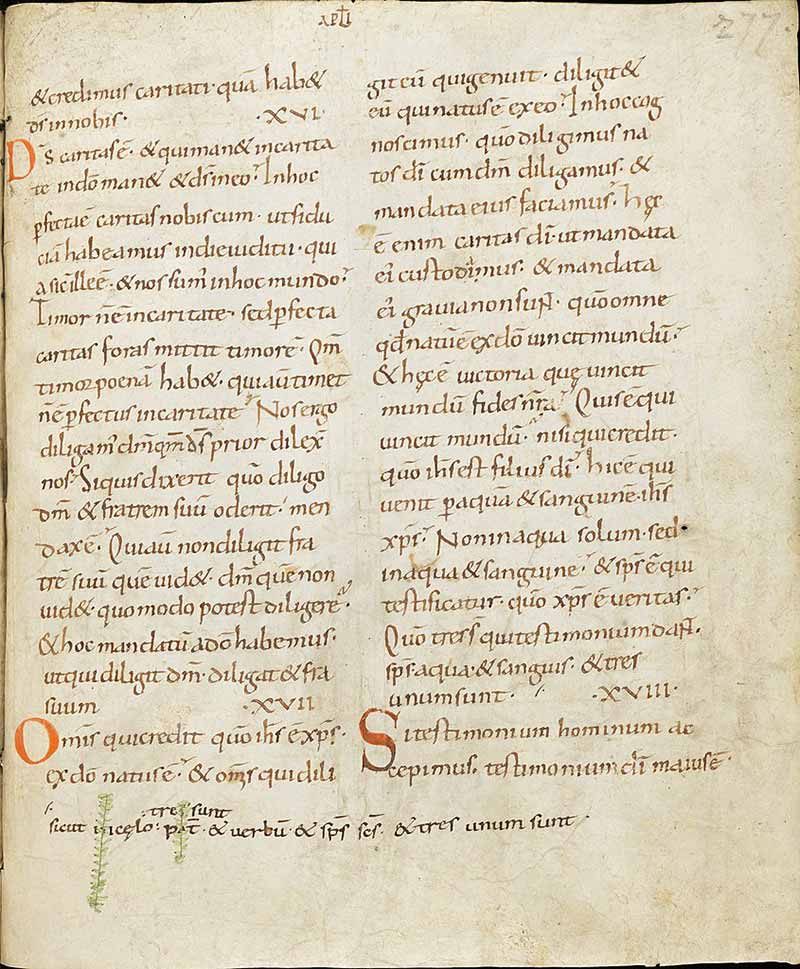

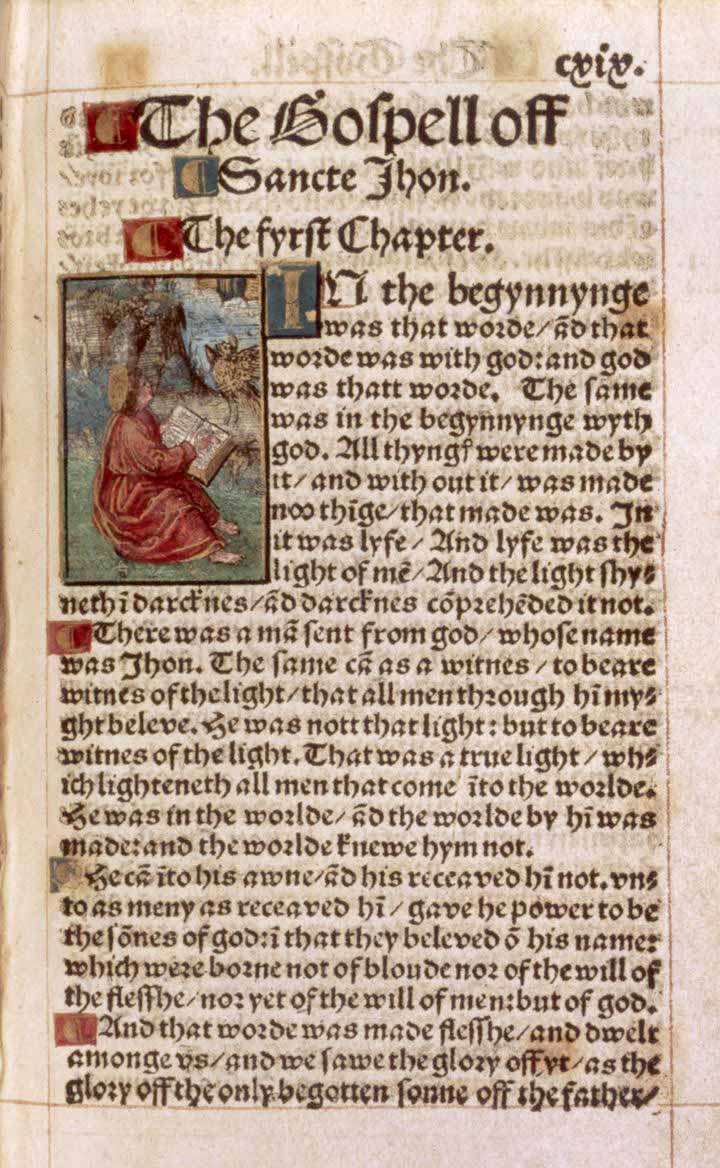

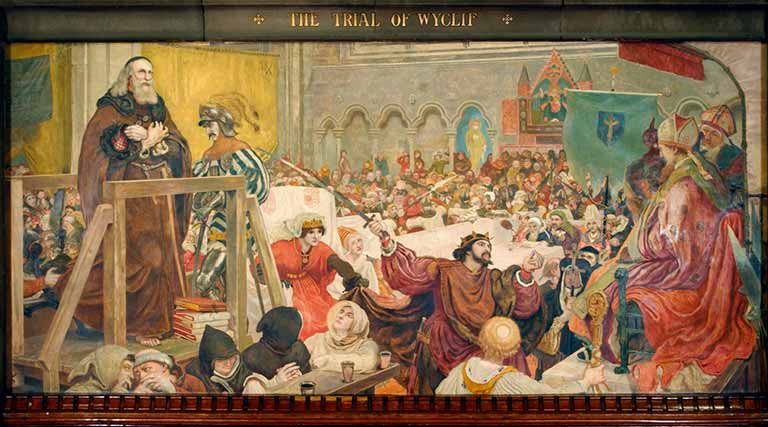

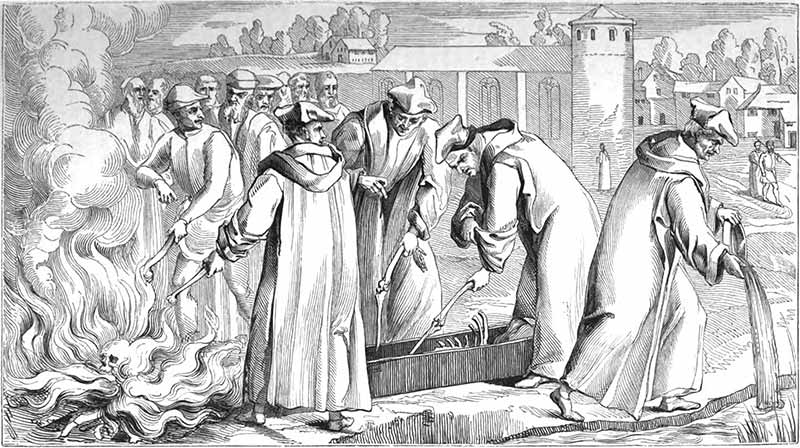

n Oxford Don possessing great academic prowess and enjoying the perks of royal patronage—the “Morning Star of the Reformation”, as he became known—was an unlikely figure of subversion, and his weapon was none other than the Word of God. It is perhaps testament to both Wycliffe’s doctrinal triumph and his own personal humility that the movement his arguments and translation produced loomed large over his own reputation and fame.

n Oxford Don possessing great academic prowess and enjoying the perks of royal patronage—the “Morning Star of the Reformation”, as he became known—was an unlikely figure of subversion, and his weapon was none other than the Word of God. It is perhaps testament to both Wycliffe’s doctrinal triumph and his own personal humility that the movement his arguments and translation produced loomed large over his own reputation and fame.