Stonewall Jackson’s Mortal Wounding, 1863

“Whether therefore ye eat, or drink, or whatsoever ye do, do all to the glory of God.” —1 Corinthians 10:31

Stonewall Jackson’s Mortal Wounding, May 2, 1863

![]() n the recent book The Smoothbore Volley That Doomed the Confederacy, by historian Robert Krick, we see, from a human perspective, an event that many historians, and Southerners in particular, believed changed history in such a way that subsequent events were just running out the clock after the All-American player had been removed from the team. Whether Stonewall Jackson’s death after the Battle of Chancellorsville “doomed” the nation or not, his removal from history secured his reputation and importance in Civil War historiography and American culture until recent times.

n the recent book The Smoothbore Volley That Doomed the Confederacy, by historian Robert Krick, we see, from a human perspective, an event that many historians, and Southerners in particular, believed changed history in such a way that subsequent events were just running out the clock after the All-American player had been removed from the team. Whether Stonewall Jackson’s death after the Battle of Chancellorsville “doomed” the nation or not, his removal from history secured his reputation and importance in Civil War historiography and American culture until recent times.

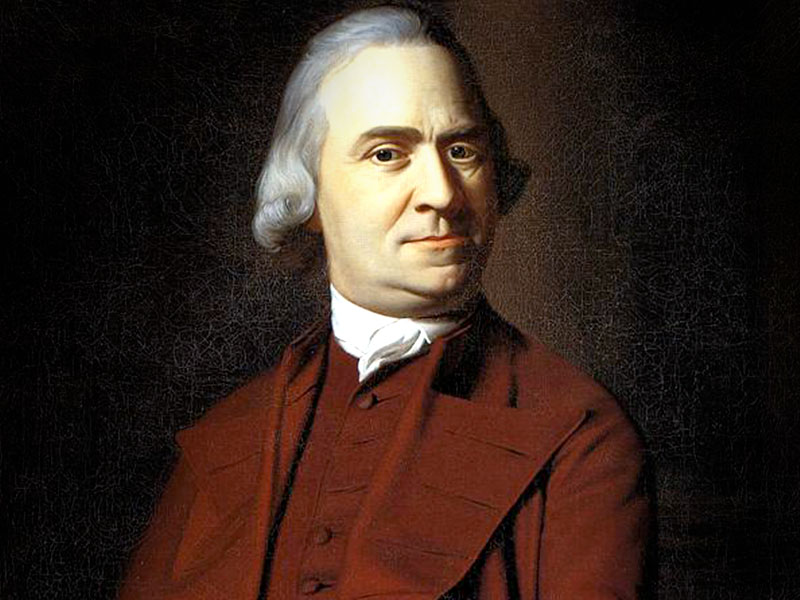

Jackson’s Mill, Jackson’s Boyhood Home

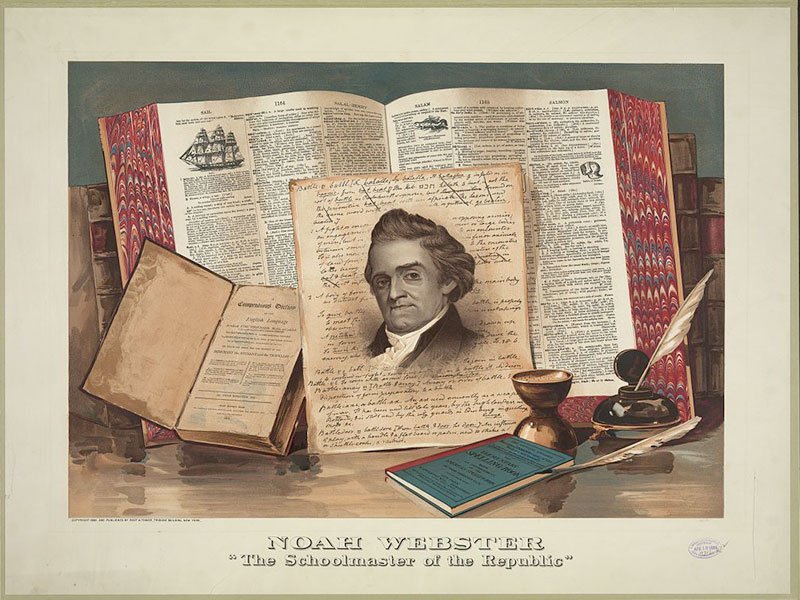

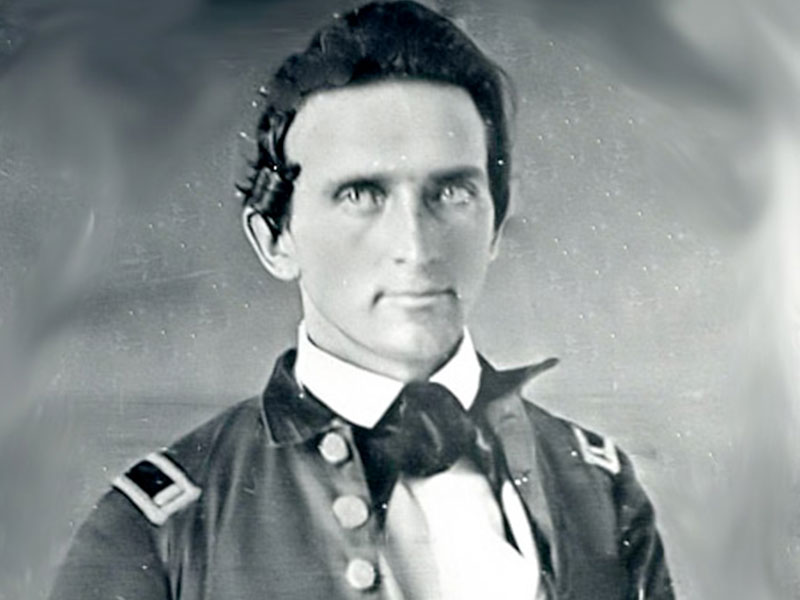

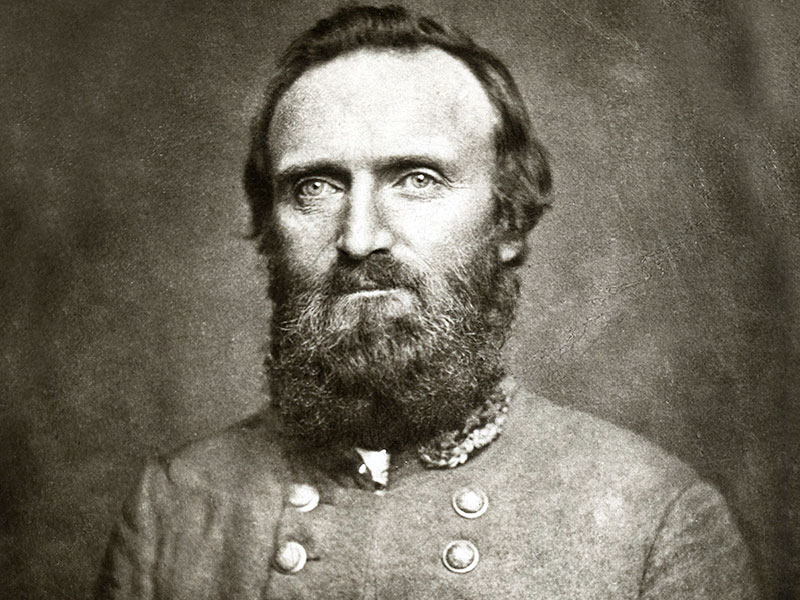

“Stonewall” Jackson as a Young Man

Thomas Jonathan Jackson was one of an untold number of young men born of Scots-Irish parents in the mountains of the Alleghenies in the 19th century. His grandparents had been transported by the English for alleged crimes in the old country and had settled in the mountains of western Virginia, raised a family in the desperate times of Indian attacks, war against Britain, and extremely high infant mortality rates. Both of Jackson’s parents died when he was young and he was raised by his Uncle Cummins, a somewhat roguish but tough parent for Thomas. Although indifferently schooled, Jackson acquired an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Awkward and unschooled, but possessing an iron will and unrelenting perseverance, Jackson had astonished his classmates in moving from last place to graduating 17th of 59 in his graduating class of 1846.

General Jackson and His Officers

Jackson with His Horse, Sorrel

From the Point, to fearless heroic performance in the Mexican War, to the classroom as a professor at the Virginia Military Institute, Jackson probably would likely have been only a footnote in history had not the Civil War plucked him from obscurity to high command in the Confederate Army. Thomas became “Stonewall” as a result of his brigade’s stand at 1st Manassas in 1861. Independent command followed and with it the “Valley Campaign.” Still studied in military history courses around the world, Stonewall Jackson with far inferior numbers of troops, bamboozled three Union armies, froze another in place, and drove the Yankees from the Shenandoah Valley in the spring of 1862.

Learn more about “Stonewall” Jackson in Living All of Life for the Glory of God: The Testimony of General Stonewall Jackson, by historian Bill Potter. Just $1.99 in the Landmark Events download store!

General Jackson was no ordinary soldier. As a devout Christian, he gave all praise to God for his successes and organized his entire life around service to Christ in all things. From his exemplary marriage to Mary Anna, to his “colored Sunday School,” to his service as deacon in his church, Jackson lived a consistent Christian life. In the army, he supported Gospel preaching by encouraging his chaplains, writing the denomination to send more preachers, and by attendance at worship services with his men. He trusted in the providence of God for the results of all his endeavors, personal and military.

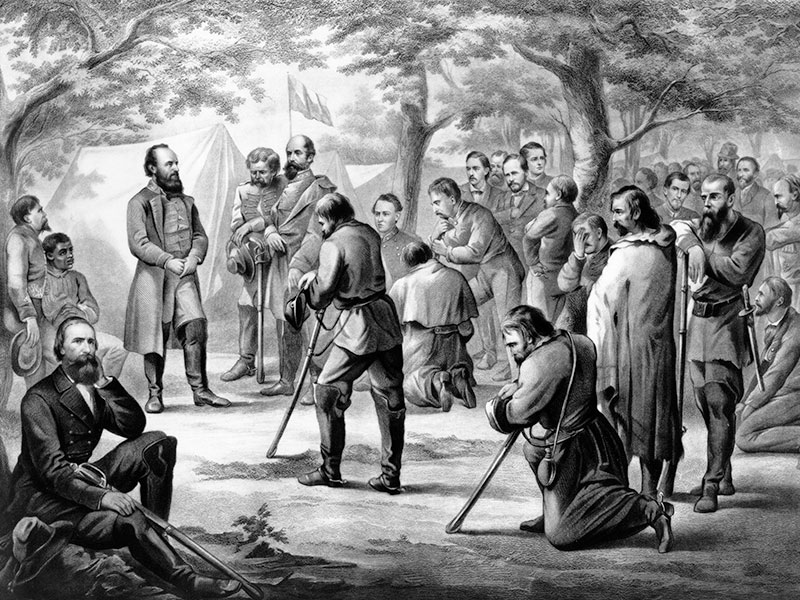

Jackson Encouraged Gospel Preaching Amongst the Army

At the Battle of Chancellorsville, Jackson, under orders of his superior, Robert E. Lee, made a forced march around a far superior Union army and attacked on their flank, wrecking all the plans of the enemy and driving his right wing from the field. In the process, Jackson received a mortal wound in the dead of night when he made an ill-advised reconnaissance of the lines. Men of his own command carrying smoothbore muskets, mistook him for enemy cavalry and fired a volley. In a week’s time, after amputation of his arm, Jackson died of sepsis, confident in his faith. His last words were “let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.”

Robert E. Lee at Jackson’s Grave

General Lee’s “Right Hand”

His ability to maneuver his Corps under the able instructions of General Lee had helped transform the Southern Army into an almost unbeatable military force on the brink of winning independence. With Jackson’s death, the dynamics of command changed and his successors never really measured up to the standard he had set. Although he was a humble Christian just doing his duty and giving God the credit, Stonewall Jackson had nonetheless earned the respect and adulation of the world, including his enemies.

Join Us This Month in Virginia!

Learn more about Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson on our Shenandoah Valley Tour! Stops include many important places in Jackson’s life including his house, church, grave, Virginia Military Institute and Port Republic Battlefield.

Image Credits: 1 Stonewall Jackson Boyhood Home (Wikipedia.org); 2 Jackson (Wikipedia.org); 3 Stonewall Jackson and Sorrel (Wikipedia.org); 4 Prayer in “Stonewall” Jackson’s camp, 1866 (Wikipedia.org); 5 “Stonewall” Jackson’s Grave (Wikipedia.org); 6 Stonewall Jackson by Routzahn, 1862 (Wikipedia.org);

Our

Our