The Battle of Franklin, Tennessee, 1864

The Battle of Franklin, Tennessee,

November 30, 1864

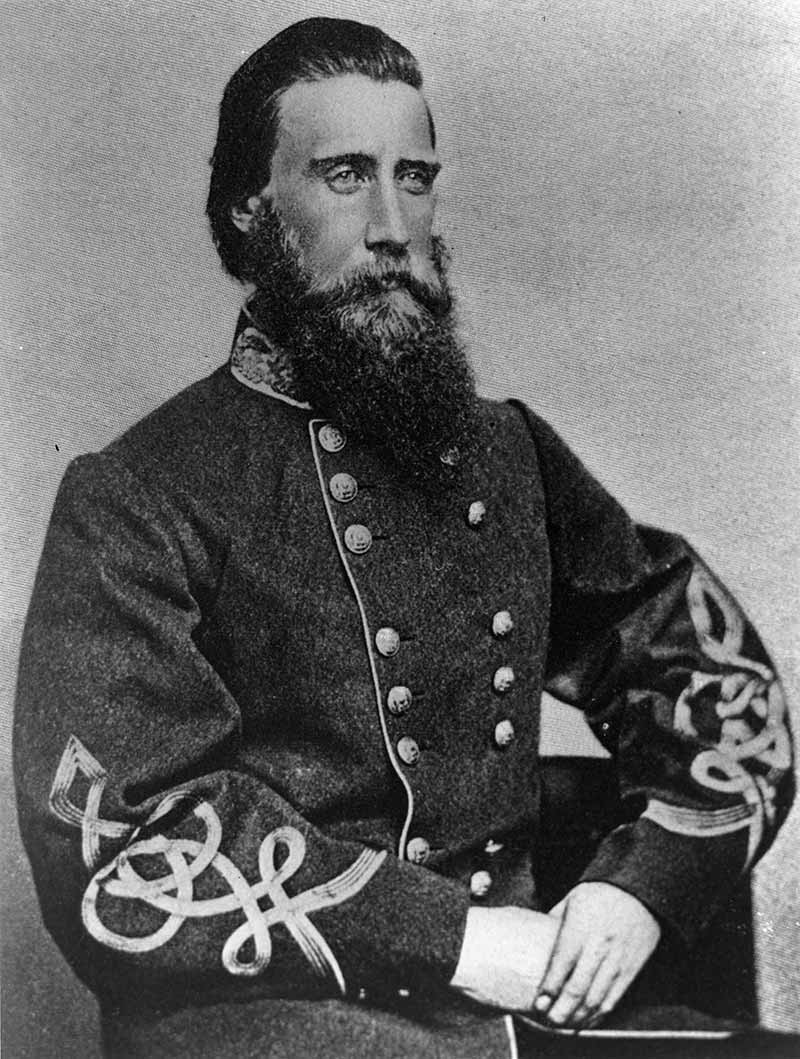

n a late Indian Summer’s day, the crippled Confederacy gave its last valiant gasp when 33,000 brave southern men and boys charged the Union Army’s entrenchments amongst the homes and businesses of Franklin, Tennessee. The last grand frontal assault of America’s Civil War, these men charged over two miles of open ground, in perfect order, with bands playing and flags unfurled, in the face of a hailstorm of bullets. The tactics of the assault were questioned by the majority of the Confederate Army’s own commanders, but having been decided upon by their superior—General John Bell Hood—there was never a braver or more ferocious fight to liberate what was the beloved hometown of many in the Army of the Tennessee.

n a late Indian Summer’s day, the crippled Confederacy gave its last valiant gasp when 33,000 brave southern men and boys charged the Union Army’s entrenchments amongst the homes and businesses of Franklin, Tennessee. The last grand frontal assault of America’s Civil War, these men charged over two miles of open ground, in perfect order, with bands playing and flags unfurled, in the face of a hailstorm of bullets. The tactics of the assault were questioned by the majority of the Confederate Army’s own commanders, but having been decided upon by their superior—General John Bell Hood—there was never a braver or more ferocious fight to liberate what was the beloved hometown of many in the Army of the Tennessee.

General John Bell Hood (1831-1879)

An artist’s depiction of the Battle of Franklin

The fighting continued after nightfall—butchery and carnage and valor displayed by both sides over every square mile—and by the end of the day, the town was in Confederate hands. But the cost had been too dear: a casualty list of over 6,000 men in those five hours of fighting left the Army of the Tennessee a shell of itself. Among the fallen were an unprecedented number of major-ranking Confederate generals, among them General Patrick Cleburne, General Otho Strahl, General States Rights Gist, General Hiram Granbury, General John Adams and General John Carter.

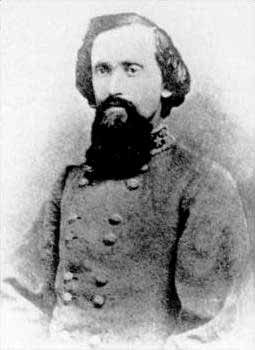

Patrick Cleburne (1828-1864)

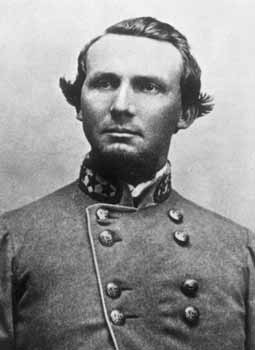

Otto Strahl (1831-1864)

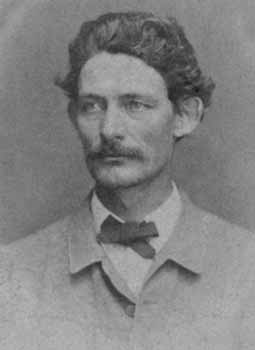

States Rights Gist (1831-1864)

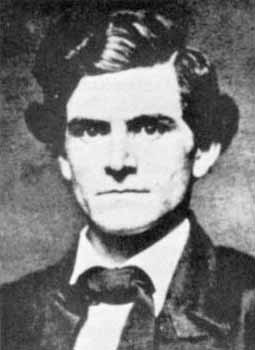

Hiram Granbury (1831-1864)

John Adams (1825-1864)

John Carter (1837-1864)

Before the battle of Franklin, there had been much uncertainty regarding the fate of the Confederate States, despite their many recent losses. Yes, Atlanta had fallen in the summer, leaving General Sherman free to complete his terrorizing of southern civilians in his infamous March to the Sea, which he had begun in the Carolinas the previous spring. In Virginia, a slow hemorrhage had been inflicted by the losses of Spotsylvania Courthouse, New Market and the brutal siege of St. Petersburg. Mobile Bay in Alabama had fallen to Admiral Farragut in August. In a last effort to regroup and seize vital railroad lines, as well as river commerce in Nashville, John Bell Hood took his Army of the Tennessee into middle Tennessee and eventually to Franklin, where in a campaign full of minor victories and substantial failures, the confederacy showcased its last grand display of fortitude.

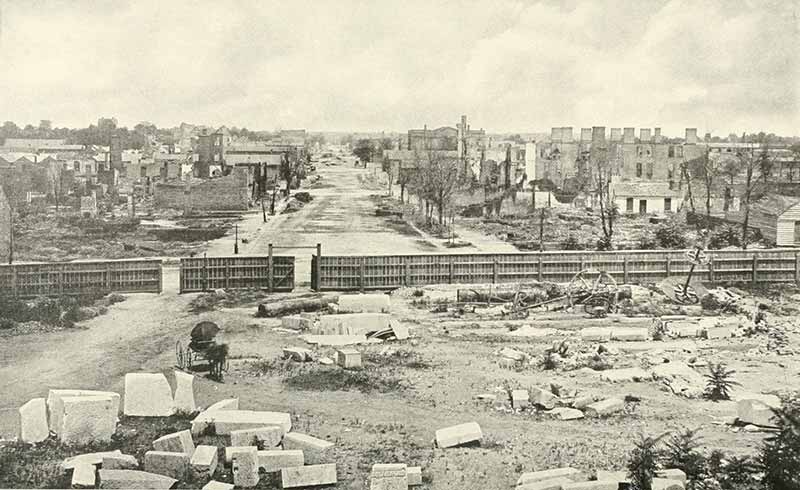

Columbia, South Carolina after Sherman’s devastating “March to the Sea”

The romance of a lost cause is often bandied about as something to be quickly sobered by realisms such as the cruel yoke of defeat and the horrors of needless death. But there is much to be recalled with great pride of the men and their officers who willingly endured the hellish conditions of war, its miseries of starvation and plague, trying with one last valiant effort to free their homes from a Federal invader bent on statism. Cultures that go down fighting rise again in some form eventually, while those who gently pass away are forgotten. Those men who charged over two miles of open field in the face of certain death knew what was at stake. They were motivated by their imperiled rights, a hard-fought inheritance encompassing the legacy of revolutionary and pioneering forefathers, generations of sacrifice and sacred beliefs. Thus, it was well that, to quote the fallen General Patrick Cleburne on that fateful day, “If we are to die, let us die like men.”

The coat that General Patrick Cleburne was wearing when he was mortally wounded during the Battle of Franklin

The McGavock Confederate Cemetery, with the McGavock home, Carnton Plantation, visible in the background

The Army of the Tennessee didn’t linger in the town of Franklin longer than a day after they had taken it, pushing on to Nashville to chase the retreating Union Army, and there meeting the extinction of the South’s last hope. But for the little town of Franklin, the echoes of their bloody liberation would last into the 20th century. In a poignant epilogue to this devastating last conflict, the citizenry took it upon themselves in the coming years to rebury the thousands of casualties who had been interred in mass graves. Prominent among these was the McGavock Family of Carnton Plantation whose home served as a field hospital during the battle and housed wounded soldiers unable to go home for up to two years after the Civil War had ended. With the backing of her husband, the minister E.M. Bounds, and the cooperation of Franklin’s townfolk, Carrie McGavock oversaw the reinterment of over a thousand confederate soldiers, identified and reburied, each with all respect and diligence in her family’s cemetery. Carrie McGavock kept a strict account of her noble charge, and for the rest of the century received the relatives and hopefuls looking to find the remains of their fathers and sons and brothers who had not been heard from since that dreadful day of November 30, 1864. Mrs. McGavock wore black the rest of her days and her personal commitment to the boys buried beneath her soil earned her the moniker “the Widow of the South”. It is now so peaceful and transporting to stand in the Carnton Cemetery, and it is one of Landmark Events’ dearest sites to tour, remembering the days of when nobility of spirit ruled and the quiet impact of every-day godliness transformed one town’s heavy legacy.

Carrie McGavock

Image Credits: 1 John Bell Hood (wikipedia.org) 2 Battle of Franklin (wikipedia.org) 3 Patrick Cleburne (wikipedia.org) 4 Otto Strahl (wikipedia.org) 5 State Rights Gist (wikipedia.org) 6 Hiram Grandbury (wikipedia.org) 7 John Adams (wikipedia.org) 8 John Carter (wikipedia.org) 9 Columbia, SC (wikipedia.org) 10 Cleburne’s Coat (wikipedia.org) 11 McGavock Cemetery & Carnton Plantation (wikipedia.org) 12 Carrie McGavock (wikipedia.org)

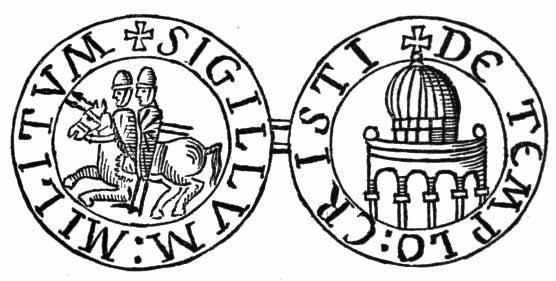

ohammed, the founder and prophet of Islam, and his successors, spread their new religion across the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia beginning in the 7th Century, through conquest, commerce, and missionaries. Those who did not convert, particularly Christians and Jews, were compelled to pay extra taxes, and bid to comply with the new cultural changes. They established new Muslim dynasties in the areas conquered, including in Palestine, where many of the historic sites from the time of Christ and the apostles were located. Christian pilgrims who travelled to those places were sometimes set upon by thieves and lawless gangs, and the Christians and Jews of those areas faced the constant pressure to convert to Islam. Moslem structures were sometimes constructed over the older Christian ones. The Roman Pontiffs began calling for the re-conquest of the Middle East, from the 11th to the 14th Centuries.

ohammed, the founder and prophet of Islam, and his successors, spread their new religion across the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia beginning in the 7th Century, through conquest, commerce, and missionaries. Those who did not convert, particularly Christians and Jews, were compelled to pay extra taxes, and bid to comply with the new cultural changes. They established new Muslim dynasties in the areas conquered, including in Palestine, where many of the historic sites from the time of Christ and the apostles were located. Christian pilgrims who travelled to those places were sometimes set upon by thieves and lawless gangs, and the Christians and Jews of those areas faced the constant pressure to convert to Islam. Moslem structures were sometimes constructed over the older Christian ones. The Roman Pontiffs began calling for the re-conquest of the Middle East, from the 11th to the 14th Centuries.