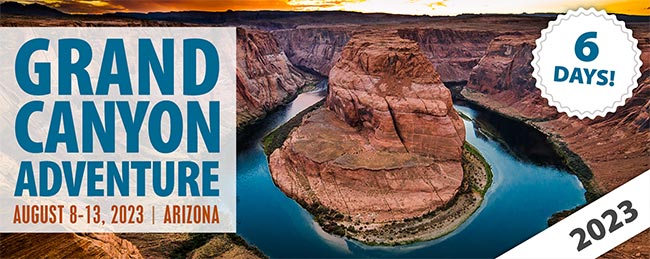

Moultrie Repels British Invasion, June 28, 1776

he year 1776 was the year of the Declaration of Independence, but also a succession of American military disasters—Long Island, Haarlem Heights, Quebec, Fort Washington and Fort Lee. George Washington redeemed American morale at Trenton at Christmas time, against a small force of mercenaries. What seems forgotten in the litany of disasters, involved a brilliant and improbable defense of Charleston, South Carolina in which the vaunted British navy suffered a stunning defeat and the army was faced down and repelled, not to return for four years! he year 1776 was the year of the Declaration of Independence, but also a succession of American military disasters—Long Island, Haarlem Heights, Quebec, Fort Washington and Fort Lee. George Washington redeemed American morale at Trenton at Christmas time, against a small force of mercenaries. What seems forgotten in the litany of disasters, involved a brilliant and improbable defense of Charleston, South Carolina in which the vaunted British navy suffered a stunning defeat and the army was faced down and repelled, not to return for four years!

Original map description reads: “An exact plan of Charles Town bar and harbour. From an actual survey. With the attack of Fort Sullivan, on the 28th of June 1776, by His Majesty’s squadron commanded by Sir Peter Parker.”

Former Royal governors lobbied Lord North’s Ministry and General Howe in New York to send a force to the South to enlist and protect the large number of Loyalists there, likely eager to join the redcoats in suppressing the rebellion. Keen to enlist Loyalists, the British chose Charleston, South Carolina as the best place to land an army. In order to do so, they would have to take Sullivan’s Island, where the American rebels had constructed a ten-foot-high makeshift sand and palmetto log fort, and placed artillery there to stop Royal Navy vessels from entering the Charleston harbor through the channel.

Ft. Moultrie, Charleston Harbor, Charleston, South Carolina as it appears today

Charleston Harbor map, showing Sullivan’s Island on the right, and the main channel into Charleston just below the island

|

Fifty sailing ships and 2,500 marines under Major General Sir Henry Clinton and Lord Charles Cornwallis were dispatched for the destruction of the defenses and seizure of the city. The flotilla included two fifty-gun double-decker “Fourth Raters”, four twenty-eight-gun frigates and numerous smaller ships mounting two hundred seventy guns. Experienced and highly regarded Commodore Peter Parker commanded the naval squadrons.

General Sir Henry Clinton (1730-1795)

|

|

General Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805)

|

General Charles Lee (1732-1782)

|

Former British officer Charles Lee, now a Continental General, was in overall command of the Charleston defenses, but Colonel William Moultrie led the 2nd Continental Regiment tasked with holding the fort on Sullivan’s Island. Lee opposed the defense of the place, considering it a death trap, but John Rutledge, newly-elected President of the Provincial Congress, supported the construction and defense of the fort. General Clinton considered Sullivan’s Island more important than Charleston itself and devised a plan whereby his marines would land on “Long Island,” (now called Isle of Palms), wade across the inlet and take the American infantry from the rear, while Commodore Parker blasted the fort to pieces from the ocean-side. Once established there, the Loyalists of South Carolina would flock to the British colors at Sullivan’s Isle.

General William Moultrie (1730-1805)

|

|

John Rutledge (1739-1800)

|

Clinton and Cornwallis landed their men on Long Island and marched them the length of the sandy spit only to find that the inlet was seven feet deep, not eighteen inches that had been reported. They set up camp and awaited the overwhelming naval attack that was coming from the opposite direction, once two large warships were over the bar and into the channel. A proclamation was sent ashore to demand that the rebels lay down their arms and return their loyalty to the Sovereign King George, or face annihilation.

Battle of Ft. Moultrie

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Peter Parker

(1721-1811)

|

At 9:30 on the morning of June 28, 1776, Parker loosed the sails of his flagship Bristol, the signal to begin the attack. Colonel Moultrie at that time was conferring with William Thomson who commanded the Third South Carolina Regiment, some North Carolina Continentals, and a special company of back-country Rangers, all armed with long-range rifles rather than the limited-range smoothbores of the redcoats on the other side of the inlet. He rode back to the fort in time to address the four hundred or so men about to give a warm reception to the English squadrons. The Americans had thirty-one guns, mostly 18 and 36 pounders, but limited amounts of gun powder and shot. They would have to make their shots count. The fort’s blue flag with a palmetto tree on it flapped in the breeze as the enemy approached. The fleet dropped anchor in a line in front of the fort and the two sides opened a “thunderous and continuous blaze and a roar.” In the confusion of the attack, three British ships ran aground on the shoals in the middle of the harbor, the spot where, in the following century, Fort Sumter would be constructed. One of those ships, the Actaeon, was set afire and abandoned by its crew when they couldn’t budge off the shoal. It blew up when the fire reached the powder magazine.

Sergeant William Jasper retrieving the flag during the Battle of Ft. Moultrie

A cannonball cut the garrison flag down and it fluttered onto the beach in front of the fort. Sergeant William Jasper of Georgia climbed out an embrasure, retrieved the flag, climbed back into the fort, and he and Moultrie together climbed upon the wall and re-installed the colors, perhaps on a sponge staff, to the cheers of the garrison. Meanwhile, Clinton and Cornwallis tried to cross the inlet breach in small boats, but their men were mowed down by Thomson’s men behind their barricades and entrenchments. The Royal Marines were forced to withdraw.

The Morning After the Attack on Sullivan’s Island, June 29, 1776, by Henry Gray.

The penciled description reads:

“The morning after the engagement on Sullivan’s Island. The ships of war having retired a few miles below the fort are on a ...repairing damages and particularly stopping shot holes between ...and...dispatch boats and other vessels are seen a few miles off, passing and repassing between the fleet and Sr. H. Clinton’s army on Long Island to the east of Sullivan’s Island.”

The naval broadsides that Parker thought would destroy the fort were absorbed by the sand and palmetto logs. Twelve Americans were killed inside the fort, but the losses on the two largest warships proved severe indeed. Moultrie’s gunners concentrated on the Bristol and the Experiment, firing hot shot (cannonballs heated glowing hot to burn up the ships) and accurate raking blasts to kill seventy men on the two ships and wounding one hundred thirty. Parker was struck twice and two captains were mortally wounded. As darkness fell, the British ships sailed away, picked up their surviving marines and rejoined the British fleet in New York. The Loyalists were thus kept “subdued and disheartened” and had to await the return of the British forces four years later, when they succeeded in capturing Charleston from the land side.

An artist’s depiction of the Siege of Charleston, 1780

In a time of loss and desperation for the young United States, a gallant defense of Charleston buoyed the spirits of the country under the leadership of William Moultrie, after whom the fort was subsequently named! The fort would play another key role in the history of the United States eighty-five years later. But that’s another story.

Image Credits:

1 Battle Plan (wikipedia.org)

2 Ft. Moultrie (wikipedia.org)

3 Charleston Harbor (wikipedia.org)

4 Henry Clinton (wikipedia.org)

5 Charles Cornwallis (wikipedia.org)

6 Charles Lee (wikipedia.org)

7 William Moultrie (wikipedia.org)

8 John Rutledge (wikipedia.org)

9 Battle of Ft. Moultrie (wikipedia.org)

10 Peter Parker (wikipedia.org)

11 William Jasper retrieves the flag (wikipedia.org)

12 Aftermath (wikipedia.org)

13 Siege of Charleston, 1780 (wikipedia.org)

|