“We will rejoice in thy salvation, and in the name of our God we will set up our banners.” —Psalm 20:5

The American Flag at Brandywine, September 11, 1777

e tend to take for granted the power of national symbols. They do not have the same grip on us that they used to, in part because they are down-played in our new multi-cultural ethos that hates our past, and partly due to the opposite — its commonplace use. The Stars and Stripes flag is likely the most common national symbol, flying from every ballpark, post office and car dealership, seen on hats and t-shirts, in front of churches and on car bumpers. On September 11, 1777 it was seen for the first time on a battlefield, the fresh symbol of a new nation. e tend to take for granted the power of national symbols. They do not have the same grip on us that they used to, in part because they are down-played in our new multi-cultural ethos that hates our past, and partly due to the opposite — its commonplace use. The Stars and Stripes flag is likely the most common national symbol, flying from every ballpark, post office and car dealership, seen on hats and t-shirts, in front of churches and on car bumpers. On September 11, 1777 it was seen for the first time on a battlefield, the fresh symbol of a new nation.

A scene from the battle of Brandywine as depicted in Nation Makers, by Howard Pyle

|

|

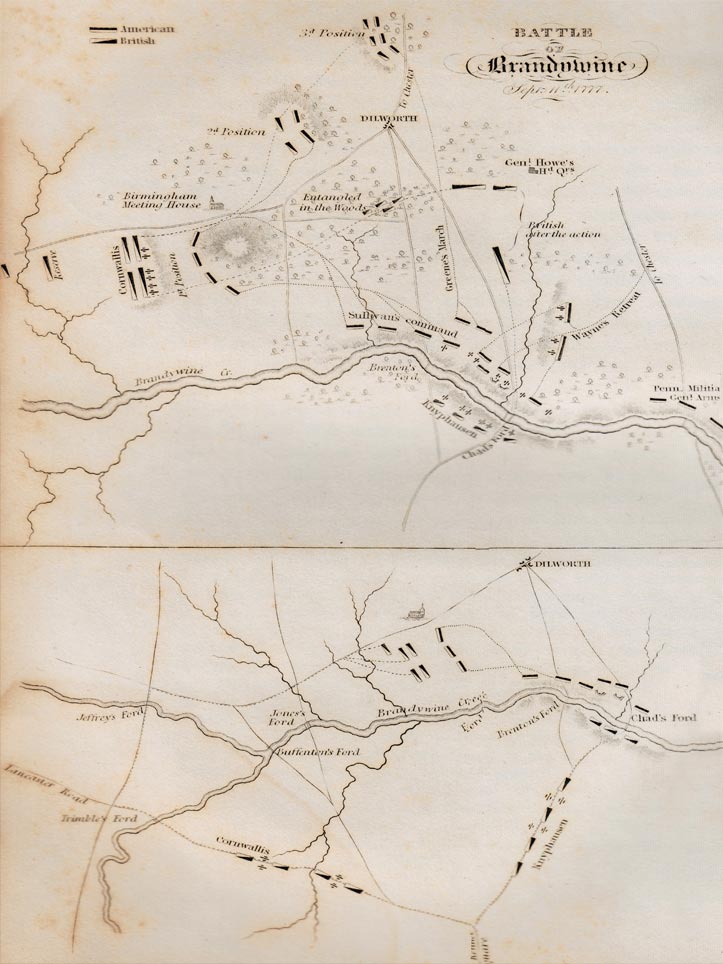

Map of the Brandywine battlefield (1830 engraving)

|

In June of 1777, the “marine committee” in Congress passed a flag resolution authorizing the creation of an American flag. They even specified that it contain thirteen stripes, red and white and thirteen stars on a blue field. They did not specify how those stars and stripes ought to be arranged, or how many points the stars should have, etc. Francis Hopkinson, Congressman from New Jersey and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, was also a flag designer. He claimed to have produced the first flag in compliance with Congressional order, although his original drawings have been lost. He designed a stars and stripes to be used as a naval banner, since he was on the committee that oversaw naval affairs. He billed Congress for the design. Vexilology experts (those who study the science of flags) claim that the idea of a national flag was relatively new, although a number of banners had already been sported on battlefields and camps.

Whatever banner George Washington accepted prior to the Battle of Brandywine, it did not prove to be standard issue yet, since he complained to Congress in 1779 that no standard flag had yet been adopted for the armies to use in battle. Nonetheless, it seems that individual state units carried Stars and Stripes by the time of the battle. A Captain of the British 33rd Foot captured the home of a militia colonel a few days before the Battle of Brandywine and seized a stand of colors, one of which was “of dark blue fringed silk with a canton of thirteen red and white stripes.”

General Sir William Howe (1729-1814), Commander-in-Chief of British forces

|

|

Gilbert du Motier the Marquis de La Fayette (1757-1834) as a Lieutenant General, 1791

|

Sir William Howe carried the British Army from New York to the environs of Philadelphia in September of 1777 with the intention of capturing the rebel capitol. George Washington with the American Continental Army met the redcoats along the Brandywine River near Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania and fought the largest and longest (eleven hours) battle of the Revolutionary War. With unprecedented battlefield heroics by Washington himself, in which he providentially survived un-hit, debuted the Stars and Stripes in combat, along with the conspicuously heroic Marquis de Lafayette, who was wounded, but would live to play a significant role in American independence.

Somewhat ironically, the American flag did not capture the emotions and meaning that we would expect today. That occurred when Major Robert Anderson lowered the garrison flag at Fort Sumter at the beginning of the Civil War in 1861. The people of the Union states were suddenly seized with a love and attachment to the Stars and Stripes that had not been there before. It became the symbol of all that had gone before in the sacrifices, creation and maintenance of the Republic and would be embraced to the death by more than 300,000 men over the following four years.

Image Credits:

1 Nation Makers, by Howard Pyle (Wikipedia.org);

2 Brandywine Battlefield Map (Wikipedia.org);

3 General Sir William Howe (Wikipedia.org);

4 Marquis de La Fayette (Wikipedia.org);

|