First Africans Brought to Jamestown in Virginia, August 20, 1619

Journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones (1976-)

|

n August 18, 2019, reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones of The New York Times Magazine launched a revolutionary program to rewrite American history by cancelling the story of the founding of American liberty and equality and replacing it with a fictional America of oppression and “slavocracy.” Instead of thirteen former colonies establishing a Confederacy of independent states in 1776, then an independent Republic in 1789, the real founding date was August 20, 1619 when the first Africans came ashore as chattel slaves in Jamestown, Virginia. The providential story is far more interesting and complicated than even a feverishly woke harridan of the politically correct mob could conjure. n August 18, 2019, reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones of The New York Times Magazine launched a revolutionary program to rewrite American history by cancelling the story of the founding of American liberty and equality and replacing it with a fictional America of oppression and “slavocracy.” Instead of thirteen former colonies establishing a Confederacy of independent states in 1776, then an independent Republic in 1789, the real founding date was August 20, 1619 when the first Africans came ashore as chattel slaves in Jamestown, Virginia. The providential story is far more interesting and complicated than even a feverishly woke harridan of the politically correct mob could conjure.

A map showing the African to Americas slave trade routes, numbers, destination countries, and their exports

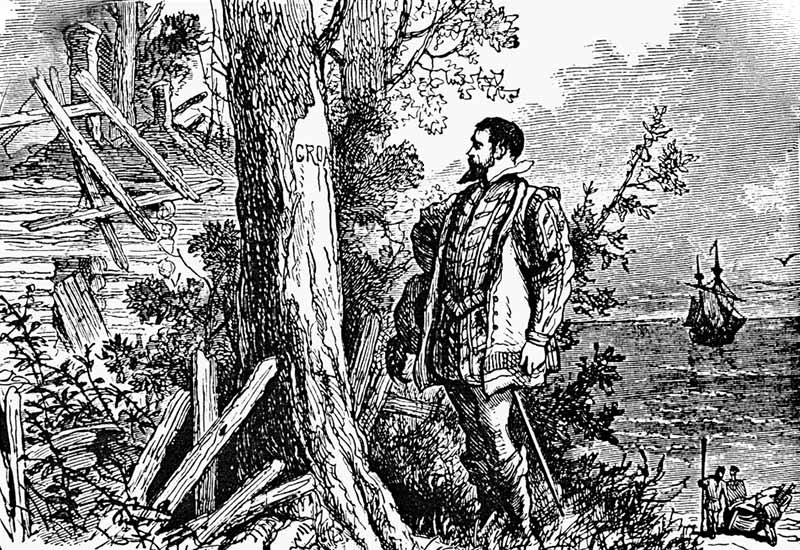

John White at the ruins of the Roanoke colony, 1590

|

England’s King James I, in order to keep peace with the Spanish after a century of conflict, prohibited maritime entrepreneurs from conducting raids on Iberian shipping in the Atlantic Ocean. Nonetheless, certain ship captains continued receiving letters of marque from other European countries such as Holland, to conduct illegal privateering ventures among the Caribbean islands and American coastlines. Captains of two such English ships, the Treasurer and the White Lion, (the latter of which fought against the Spanish Armada and later evacuated settlers from Roanoke Island), apparently assumed their chances of profit and success were worth the risks. In the summer of 1619 they attacked the Spanish slave frigate San Juan Bautista in the Gulf of Mexico, no doubt hoping the ship contained profitable cargo. To their surprise, and no doubt disappointment, they came away with sixty or so Angolans, a burden they neither sought, nor wanted. They sailed to the first permanent English-speaking colony in the New World to rid themselves of the couple dozen Africans still aboard after the death of or trading off of the rest.

A replica of the frigate San Juan Bautista

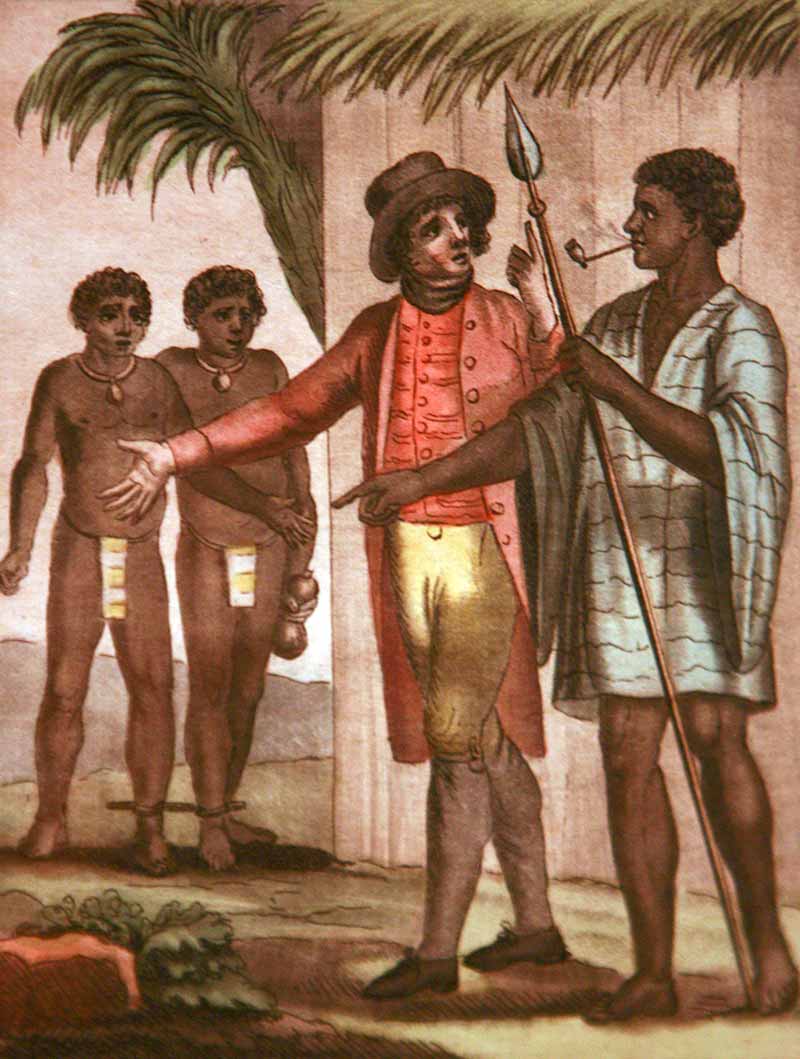

An African slave-trader and a European slave-trader discuss a couple of slaves

|

The Portuguese had established ports of call and trade relations along the coast of the African Congo in the late 15th and early 16th Century. A vigorous slave trade already existed and had for centuries in various parts of Africa, led by Muslim slavers and aggressive African tribes. As Islam spread below the Sahara and into tropical Africa, the Portuguese and later the Spanish, in the 16th Century, bought slave-laborers for their new islands and land acquisitions in their respective burgeoning empires in the Western hemisphere. The Ndongo tribes of the Congo region learned Portuguese and converted to Roman Catholicism, but they managed to repel the Portuguese attempts to overrun and conquer them. In general, the Ndongo were excellent cattlemen and extraordinary crafters of jewelry and textiles. At the time of our story, Spain had taken over Portugal and picked up much of their slave trade along the African Coast. They also brought the Spanish Inquisition to the more tolerant Portuguese, and accused the Lisbon government of harboring Jews in Mpinda, the base of operations in the Congo. The Portuguese moved their trading capitol 150 miles further south to Luanda, bringing them closer to their African slave-trading partners, as well as the Ndongo tribe.

A valley in former Mpinda (now called Soyo) in the province of Zaire in Angola,

at the mouth of the Congo River

Luís Mendes de Vasconcellos (1542-1623) Portuguese colonial Governor of Angola from 1617 to 1621

|

By 1617 a convergent series of events struck hard at the Ndongos. A civil war broke out within their nation; secondly, a tough army of mercenaries known as the Imbangala appeared on their borders; and a slave-labor shortage in the Caribbean—along with the Spanish policy of allowing their governors to take a share of the slave trade proceeds—created a demand for increasing the acquisition of captives. The Portuguese Governor allied with the roving Imbangala cannibals (well known for the ruthless slaughter of their enemies), took conquered young men into their army, and seized captives to be sold into slavery. Governor Vasconcelos led the combined Portuguese army (with artillery) and the Imbangala into an attack into the highlands of the Ndongos. Their regular army was elsewhere fighting the civil war, but a call went out to the militias and fearless lion-hunting herdsmen of the tribe to bring their spears, axes, and bows and arrows to repel the enemy. The European guns in the end, after a bitter struggle, overcame the valor of the Ndongos and many were captured, to be sent into the slave pipeline which led to America. And thus, the Bantu-speaking Africans with Portuguese names came to Jamestown, Virginia aboard English ships in August of 1619.

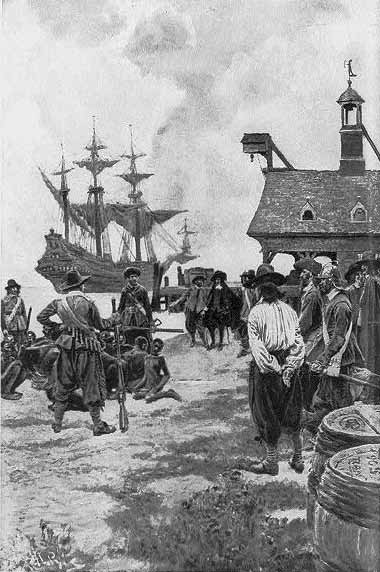

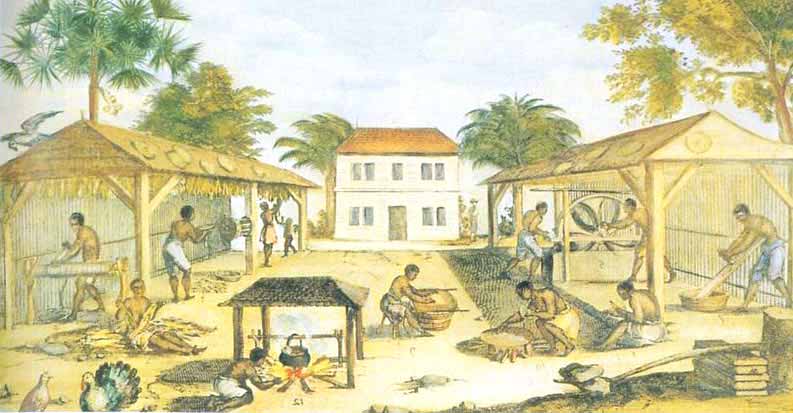

The arrival of the first Africans in Jamestown, Virginia, 1619

|

The sponsor of the piratical ships, Lord Rich, had sent his captains to the Caribbean to raid the Spanish Main and to operate out of Jamestown, in direct disobedience to the orders of King James. Governor Yeardly took half of the Bantu men and women, and Abraham Piersey—a local merchant-planter—took the other half to work his plantations. By 1624, those Angolan experts in crops and cattle turned the Piersey’s property into the first two successful financial ventures in the colony. They diversified the crops from just tobacco, became weavers, tanners, cattlemen and perhaps iron workers, skills that came with them from Africa. The Africans were not at once given the same status as white indentured servants, but over the next thirty years they pursued their freedom in a number of ways, using their wiles, colonial courts, and the political turmoil their presence engendered, in London and America.

Slaves processing tobacco on a 17th Century Virginia Plantation

Some plantation owners freed their Africans, some of whom became land owners themselves, intermarried with whites and Indians, and, in one case, kept a fellow African as a slave. It is likely that a number of both African and English servants received their freedom by supporting Parliament against King Charles I in the English Civil War. African born Benjamin Doll could read and write English and eventually owned a three-hundred-acre plantation in Surrey County. He married a fellow Ndongo and his son prospered also. Their family has been able to trace their success down through many generations. From that first generation of Africans—with names like Isabel, Domingo, Francisco and Margaret—married and raised families, some of whom moved westward with the expanding colonies. From those first Angolans came future cowboys, planters, lawyers, and a Confederate general. The providential stories of many Americans is one of striving for freedom, achievement, and blessings, even though for some it involved a long voyage chained in the hold of a ship, headed for slavery, but never giving up hope and forging relationships that defied history, which is never neat and always complicated.

For further reading we recommend The Birth of Black America: The First African Americans and the Pursuit of Freedom at Jamestown by Tim Hashaw (2007).

Image Credits:

1 Nikole Hannah-Jones (wikipedia.org)

2 Slave trade map (wikipedia.org)

3 Roanoke (wikipedia.org)

4 San Juan Bautista replica (wikipedia.org)

5 Slave traders (wikipedia.org)

6 Soyo (wikipedia.org)

7 Governor Vasconcellos (wikipedia.org)

8 Africans arrive at Jamestown (wikipedia.org)

9 Tobacco Plantation (wikipedia.org)

|