“God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble. Therefore we will not fear though the earth gives way, though the mountains be moved into the heart of the sea.” —Psalm 46:1-2

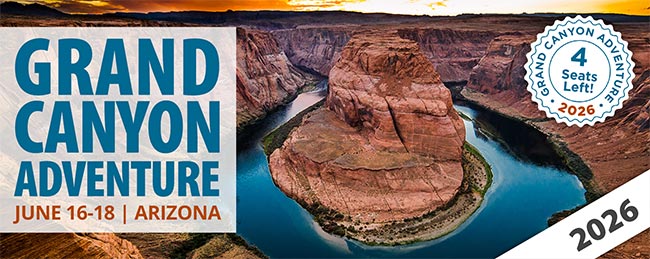

Phoebe Yates Pember Is Appointed

Chief Matron of Chimborazo Hospital,

December 4, 1862

t is the case for many of us that, when studying any past war, the least compelling elements are its tomes of detailed strategies, minute battle plans and laborious politics. Indeed, sometimes such details are enough to deter seekers from ever opening a history book again. But there are sources by which we can approach these conflicts that provide for us a most vivid, extraordinary tale of human capacity and divine grace. t is the case for many of us that, when studying any past war, the least compelling elements are its tomes of detailed strategies, minute battle plans and laborious politics. Indeed, sometimes such details are enough to deter seekers from ever opening a history book again. But there are sources by which we can approach these conflicts that provide for us a most vivid, extraordinary tale of human capacity and divine grace.

Phoebe Yates Levy Pember (1823-1913), photographed in 1855 |

Among the countless books written about America’s Civil War—both by those who lived it and those who study it—there stands alone one great genre to rival them all: the memoir. America’s literacy rate was one of the greatest in the world at the time of the war, and as a result, the diaries, letters, field reports and compiled memoirs remain to us a spectacular source of study. Chief among these—and in no way diminished by their lack of front-line knowledge—are those sources written by women. As the war was primarily waged against and amongst women of the Southern states and their families, the ratio is accordingly disproportionate.

Author and Harvard historian Drew Gilpin Faust gave specific praise to them when he said:

“The diaries and memoirs of Confederate women—especially those who served in hospitals—are indispensable. They reveal the collapse of the domestic sphere into the public world of war, and they document suffering and resilience in ways no military record can.”

Mary Chestnut (1823-1886) kept an extensive diary during the Civil War from the perspective of a Southern woman. Her diaries were later published as the famous and oft-quoted Mary Chestnut’s Civil War |

It is women who notice the minute in war; they aren’t the ones called to the fighting or the often immediate sacrifices, but they are the ones first to notice the effects of it. It is women who sew the burial shrouds for the babies they once swaddled. Life, culture and the beating heart of the nation is made up of families in their homes. To quote G.K. Chesterton, “. . .there is nothing more extraordinary than an ordinary man, his ordinary wife, and their ordinary children.”

One such heroine was the Matron of the world’s largest hospital, located in Richmond, Virginia. Phoebe Yates Levy (later, Pember) was born on August 18, 1823 to Jewish parents in Charleston, South Carolina. Her father, Jacob Levy, was a successful merchant and, because of their wealth and status, they socialized with the city’s elite.

In 1856, Pheobe married outside her faith to Thomas Pember of Boston. Their marriage only lasted five years before her husband succumbed to tuberculosis in July 1861, months after war had broken out between the states.

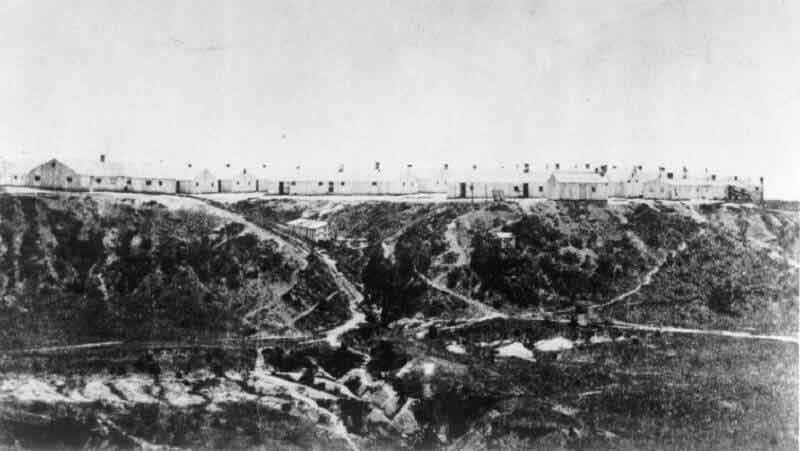

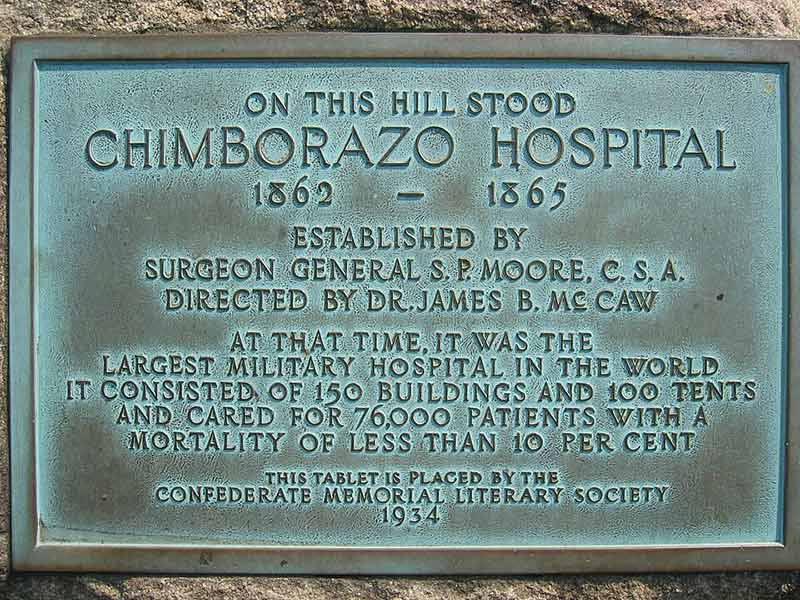

As this cruel war progressed longer than the brief span of time anticipated by its architects, and since its toll had grown alarmingly by the first anniversary of Fort Sumter, adaptations were made in everyday infrastructure to meet its challenges. The chiefly agrarian South attempted to turn itself into an industrial giant overnight, its prosperous shipping commerce became reliant solely on blockade runners, and its hospitals had to adapt from attending civilian maladies to keeping alive the handiwork of battlefields. It is telling of the butchery produced by this conflict that the Confederacy’s capital of Richmond, Virginia held the world’s largest hospital of its time, Chimborazo.

One of the buildings of Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, VA—now Chimborazo Medical Museum at Richmond National Battlefield Park

In late 1862, Phoebe Pember was asked by her good friend and wife of the Confederate Secretary of War, Mary Pope Randolph, to accept the newly created position of Hospital Matron there. Phoebe Pember would remain at this post until the final outcome of the war, two-and-a-half years later, treating over 76,000 soldiers.

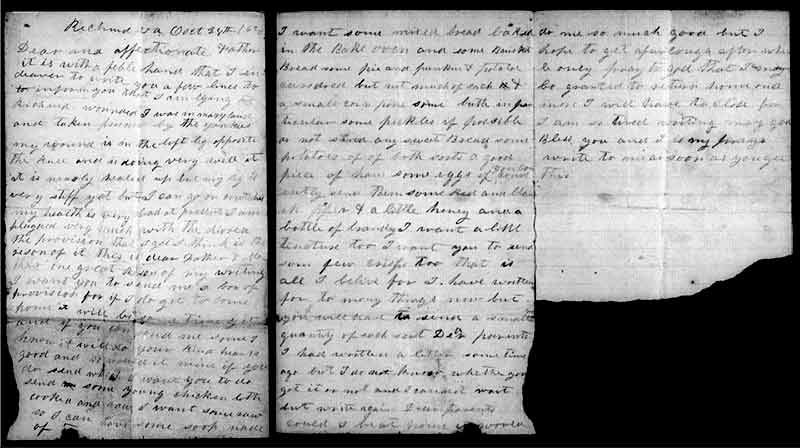

Pember did not practice medicine herself, but she proved to be a most successful administrator. As Chief Matron, Pember oversaw the nursing operations in the second of the hospital’s five divisions with limited supervision from a chief medical officer. To her fell the duties of cooking and distributing food to packed wards of over 15,000 men during years of increasing deprivations. She was the one who oversaw her patients’ correspondence, often writing the last letters home of the men under her charge.

A letter from a soldier at Chimborazo Hospital

Her memoir details even her most mundane duties, such as her three-year-long fight to maintain control over the hospital’s prized whisky barrel—something contended over by the male hospital staff to the point of calling in the Secretary of War to intercede. He, after displaying disgust at having been bothered with so small a thing, sided with Pember. After that, what little whisky was left in the Confederacy was administered by her to those prescribed it until the war’s end.

Her main preoccupations in her memoir seem to be the highs and lows, the noble and the petty displays of human nature, how these are exhibited to the extreme during times of hardship. She writes of the lengths she would go to in order to answer a sick man’s request, and the delight the simplest of favors or the presence of a friend might produce.

A model of the full extent of Chimborazo Hospital as it was during the Civil War, Richmond National Battlefield Park

Although not a nurse, Phoebe quickly became involved in the surgical aspects of the hospital, nurses being so few. She became such a staple among the wards that if she were to pass one of the men without greeting him, it would be taken as a singular offense. When taking a much-needed furlough in 1864, the first holiday she had taken in years, one boy burst into tears at the news, saying Pember might as well kill him now, since he would not survive without her nursing. Her meticulous and unscrupulous drive for cleanliness, nourishing food, and the promotion of health might have made her aggravating to her fellow workers, but was hailed as saintly by her patients.

After the battle of Fredericksburg, Pember once had a patient that had a shattered femur. He was not expected to live, but the doctors put him back together as best they could, and after fighting for two weeks to keep the fever at bay, he seemed to make a recovery. Growing bold, he rolled over in his bed, unsupervised, and a shard of his shattered bone nicked open his artery. The doctor was called and could do nothing to save him.

Phoebe Pember kept pressure on the wound to staunch the bleeding for over seven hours. When the boy asked her what would happen if she let go, she had no recourse but to reply that he would die. “Then let go,” he told her bravely; he was ready for heaven. This veteran caretaker could not bring herself to do so; he was only 18 years old. She stayed by his bedside until the enormity of this choice, lack of sleep and food, and a rush of emotions made her faint for the first and only time in the entire war. When she came to, he was gone.

Chimborazo Hospital, 1865

Another patient she fought to save for over six days, until the fever took him. She described it thus:

“On the sixth morning, on my entrance, he turned an anxious eye on my face, the hope had died out of his. What comfort could I give? Only silently open the Bible and read to him without comment the ever loving promises of his maker. Glimpses too of that abode where the weary are at rest. Tears stole down his cheeks and he was not comforted. ‘I am an only son’ he told me, ‘and my mother is a widow. Go to her if you ever get to Baltimore and tell her that I died in what I consider the defense of civil rights and liberties. I may be wrong, God alone knows. Say how kindly I was nursed, and that I had all I needed. I cannot thank you for I have not breath, but we will meet up there.’ He pointed upward and closed his eyes that never opened again upon this world.”

A plaque commemorating the significance of Chimborazo Hospital

Between accounts of heart-rending final moments, Pember makes observations on nutrition, the human spirit to survive, and the dire straits to which all Confederate administrators succumbed during the last, barren year of the war. She voices deep horror and empathy for those managers of prisoner-of-war camps who were held responsible for the starvation of their prisoners. She recounts with a passion driven by the desire for justice just how many Southern prisoners she nursed back to health after prisoner exchanges, all of whom were similarly starved by their Northern counterparts—although the excuse of a blockade was not present in the North. By the end of the war she had to divide a few pans of cornbread between thousands of men, choosing which would ultimately live or die, by means of sustenance, rather than bullet or sword. Her greatest heroes in this time were the equally strained Southern citizenry:

“To those cognizant of their great contributions, it seemed that the non fighting people of the Confederacy had worked as hard and exercised as much self sacrifice as the soldiers in the field.

There was an indescribable pathos lurking at times in the bottom of these home boxes, put up by anxious wives, mothers and sisters. A sad and mute history shadowed forth by the sight of rude, coarse, homespun pillowcases or pocket handkerchiefs, adorned even amid the turmoil of war and poverty with an attempt at a little embroidery, or a simple fabrication of lace for trimming. The silent tears dropped over these tokens will never be sung in song or told in story. The little loving expediences to conceal the want of means that each woman resorted to—thinking that if her loved one failed to benefit by the result, other mothers might reap the advantage—is a history in itself. Piles of sheets, cotton carded and spun in the one room at home where the family perhaps lived, ate and slept in the backwoods of Georgia. Bales of blankets called so by courtesy but only in fact drawing room carpets, the pride of some thrifty housewife, perhaps her only extra adornment in better days, now cut up for field use. Dozens of pillow slips, not of the coarse product of the home loom which would be too harsh for the cheek of the invalid, but of the fine bleached cotton of better days, suggesting personal undergarments sacrificed to the sick. And flannel piles for the staunching of blood, derived from almost every dressing gown and skirt in the country. All evidences of the energetic labor and loving care of the poor, patient ones at home, telling an effecting story that knocked on the portals of the heart. And with them came letters. Those are too sacred to print.”

Shortly before the end of the war, while Richmond and her hospital were being subjected to one of the most significant bombardments of the war, Phoebe Pember wrote the last will of a dying young man. He was a Marylander, had not been home in four years, and never anticipated being allowed back even were he to live. His last name was Key—a grandson of Francis Scott Key, the author of our national anthem. The hospital staff had mostly abandoned their posts during the bombardment, and so Phoebe Pember took it upon herself to put his dead body in a cart and drive him to the heights outside of town for burial. In the graveyard she met a pastor who was praying over his dead son. Together they dug a grave amidst pouring rain and shelling canister. Together they buried a scion of one of America’s greatest families, unknown but not unkept. He was one of thousands that Phoebe herself buried and mourned, almost entirely alone.

The Confederate section of Oakwood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia where the Confederate dead of Chimborazo were buried, as marked by wooden boards in this Civil War-era photograph—these boards would later be replaced by more permanent concrete markers

There have been periods of great grief in our nation’s history; our Civil War is chief among them. It brought out savagery in some, in others it was their noblest chapter. Phoebe Pember’s wretched work required a living faith in an incarnate Savior, and what one of her contemporaries described as her “will of steel under a suave refinement.” After her work was done, she committed her memory of those thousands of forgotten mothers’ sons into her memoir. As Robert E. Lee once wisely said, “duty is ours, the consequences are God’s.”

Image Credits:

1 Mary Chestnut (wikipedia.org)

2 Phoebe Pember (wikipedia.org)

3 Chimborazo Medical Museum (wikipedia.org)

4 Soldier’s Letter (wikipedia.org)

5 Chimborazo Model (wikipedia.org)

6 Chimborazo, 1865 (wikipedia.org)

7 Chimborazo Plaque (wikipedia.org)

8 Oakwood Cemetery (wikipedia.org)

|