Lincoln Orders the Largest Mass Execution in American History, 1862

“You shall not fall in with the many to do evil, nor shall you bear witness in a lawsuit, siding with the many, so as to pervert justice.” —Exodus 23:2

Lincoln Orders the Largest Mass Execution in American History, December 26, 1862

![]() he Civil War is largely lauded for its impact in regards to ensuring an “indivisible union”, the emancipation of slaves, and laying the foundation for America’s emergence as a world power in the 20th century. There was, however, a tremendous price paid for this, and few instances display that so grimly as the treatment of America’s Native Tribes out west.

he Civil War is largely lauded for its impact in regards to ensuring an “indivisible union”, the emancipation of slaves, and laying the foundation for America’s emergence as a world power in the 20th century. There was, however, a tremendous price paid for this, and few instances display that so grimly as the treatment of America’s Native Tribes out west.

A Sioux Village in Wyoming, 1859

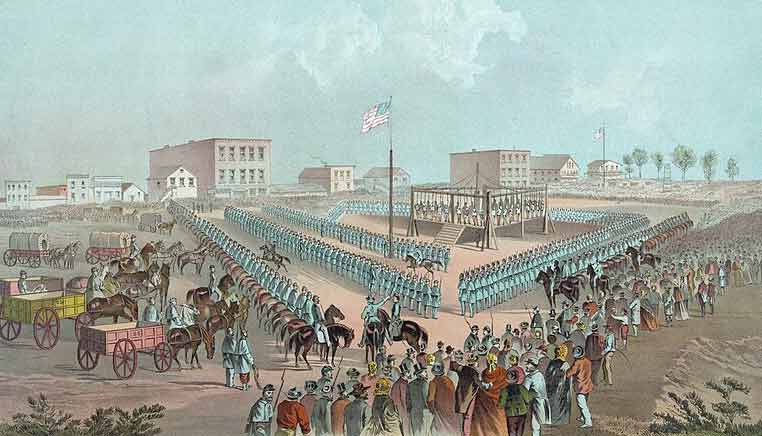

The following story is to highlight only one such event: the mass hanging of 38 Dakota men in Mankato, Minnesota, on December 26, 1862. These men were sentenced without due process or recourse, and were hand-picked by President Lincoln himself to make an example of them. Though the story itself is brief, the reflection it casts on the emergence of an arbitrary central power is boundless and chilling.

Many historians have put forth that Abraham Lincoln’s declaration of war against the South marked a paradigm shift toward centralized government power, dismantling the checks and balances that had previously served to restrain federal overreach and protect the rights of states and individuals. This consolidation of power not only transformed the conduct of war between western nations—allowing for the wholesale targeting of non-combatants and bypassing Congressional authority for declarations of hostilities—but also set a grievous precedent for penalizing dissenting people groups.

Sioux women cooking and caring for children in their encampment

The most grievous victims of this emerging American behemoth were its civilians. These included Northern detractors of the Civil War, Southerners subjected to previously unimagined atrocities, and Native Americans such as the Dakota people.

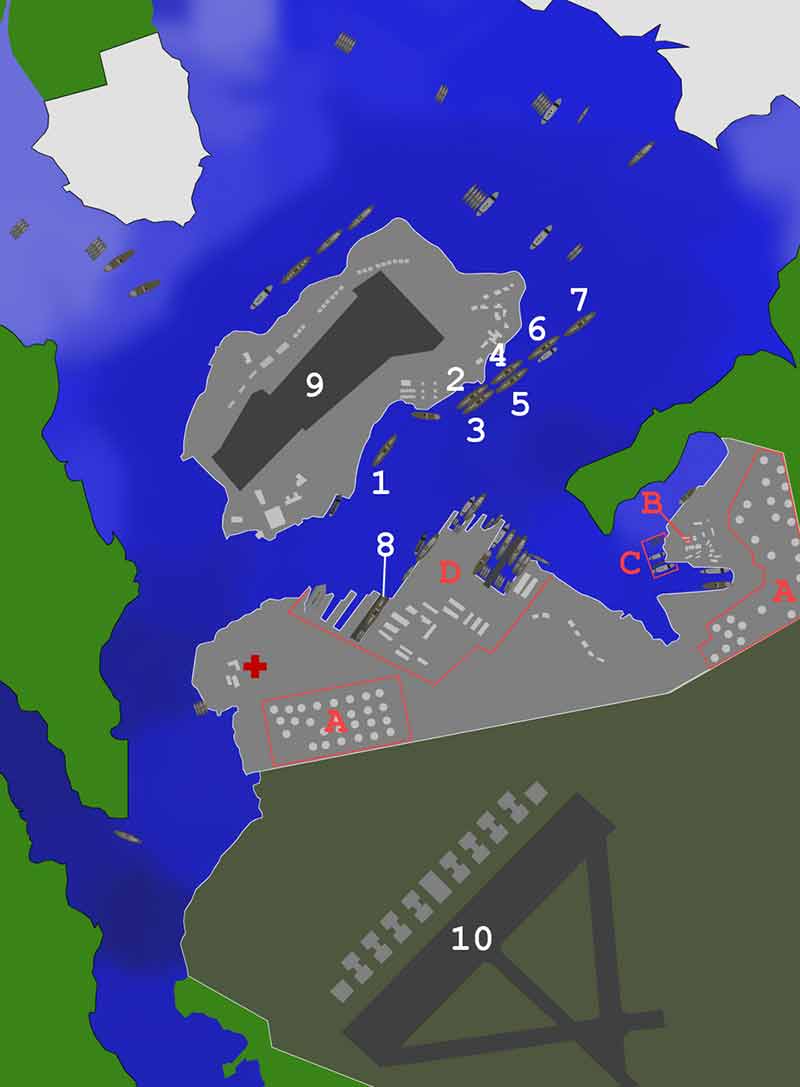

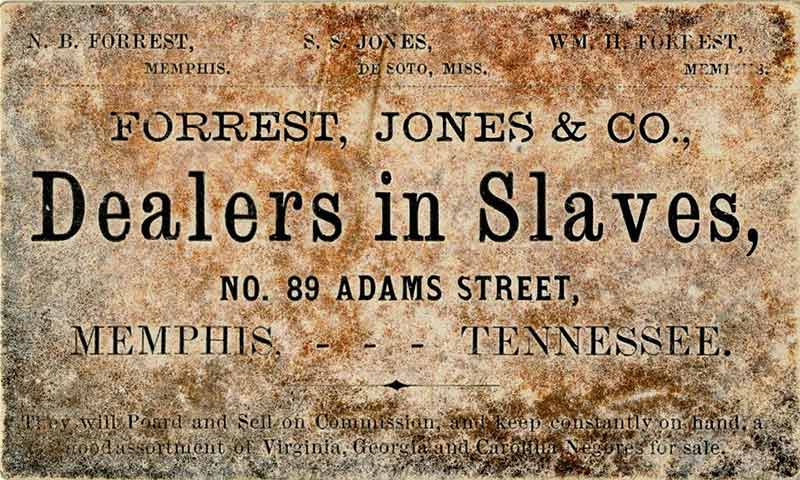

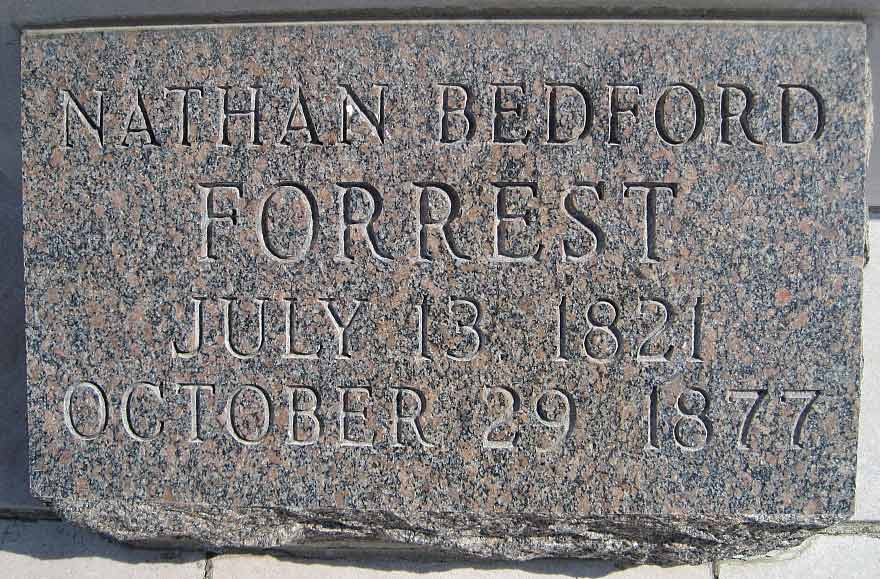

An 1851 Treaty between the Sioux people and the government of Minnesota

The bare facts of this story are thus: in 1851, ten years before the start of the Civil War, certain tribes belonging to the Sioux Nation* in Minnesota sold twenty-four million acres of land to the federal government for $1,410,000. Ten years later, thousands of settlers were pouring onto both these lands and also those which the Natives retained. There was such corruption in the federal government—preoccupied with the Civil War as it was—that almost none of the promised money was ever paid to the Sioux. To make matters worse, in 1862 a crop failure meant that the Sioux were starving, yet lacked their previous broad territory or the promised pecuniary assets to alleviate this. Considering the treaty thus broken, the Sioux revolted.

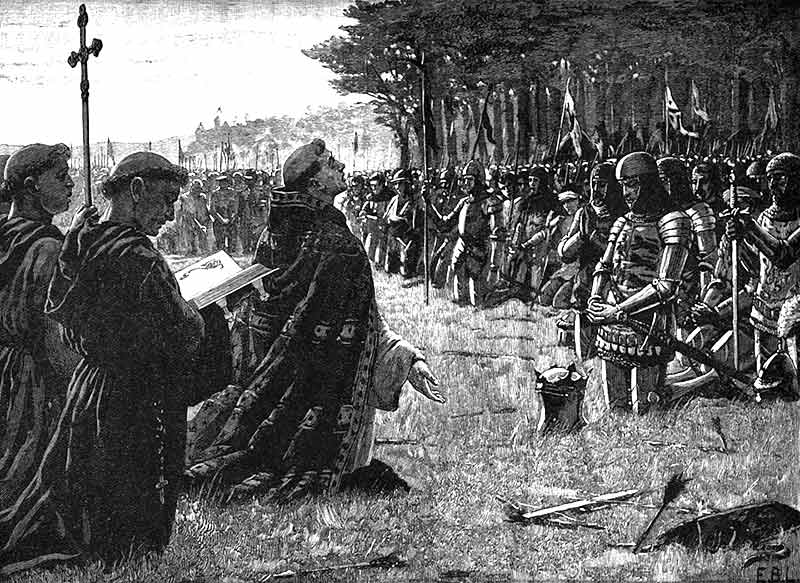

After the treaty was broken, the Sioux revolted, attacking local farmers and settlers

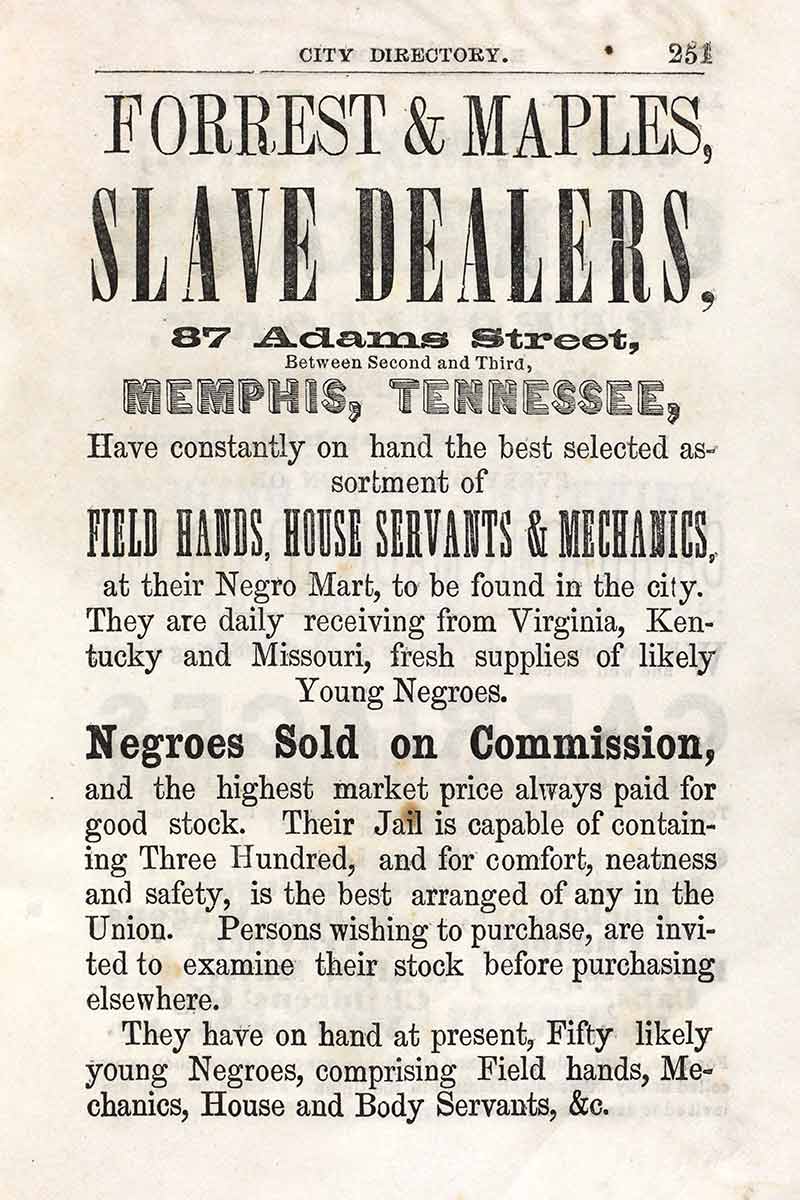

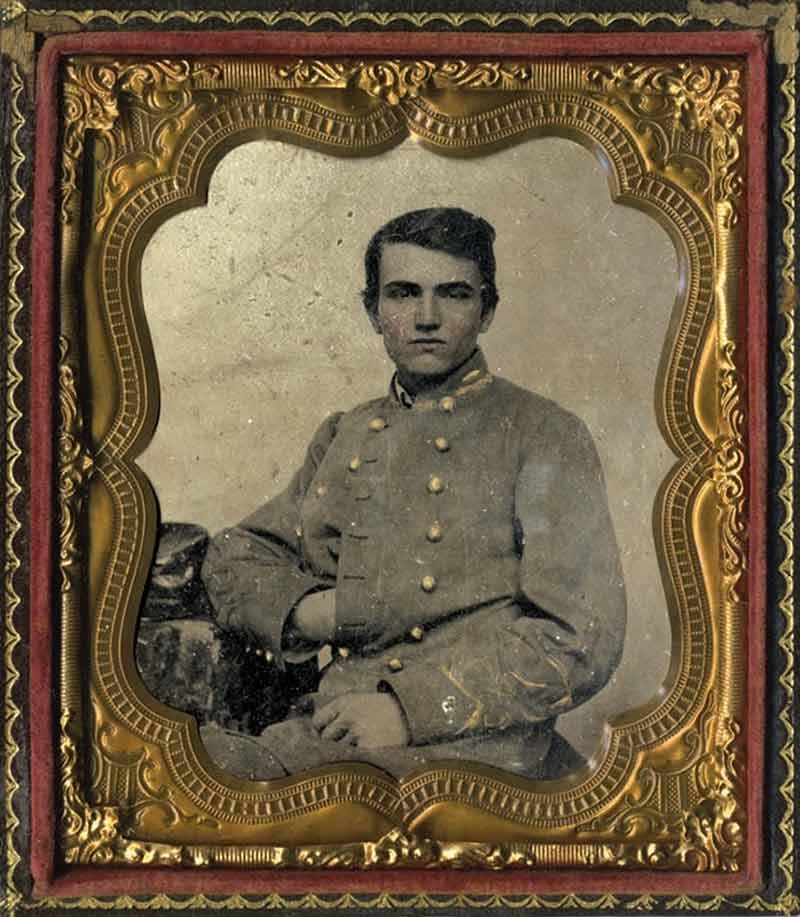

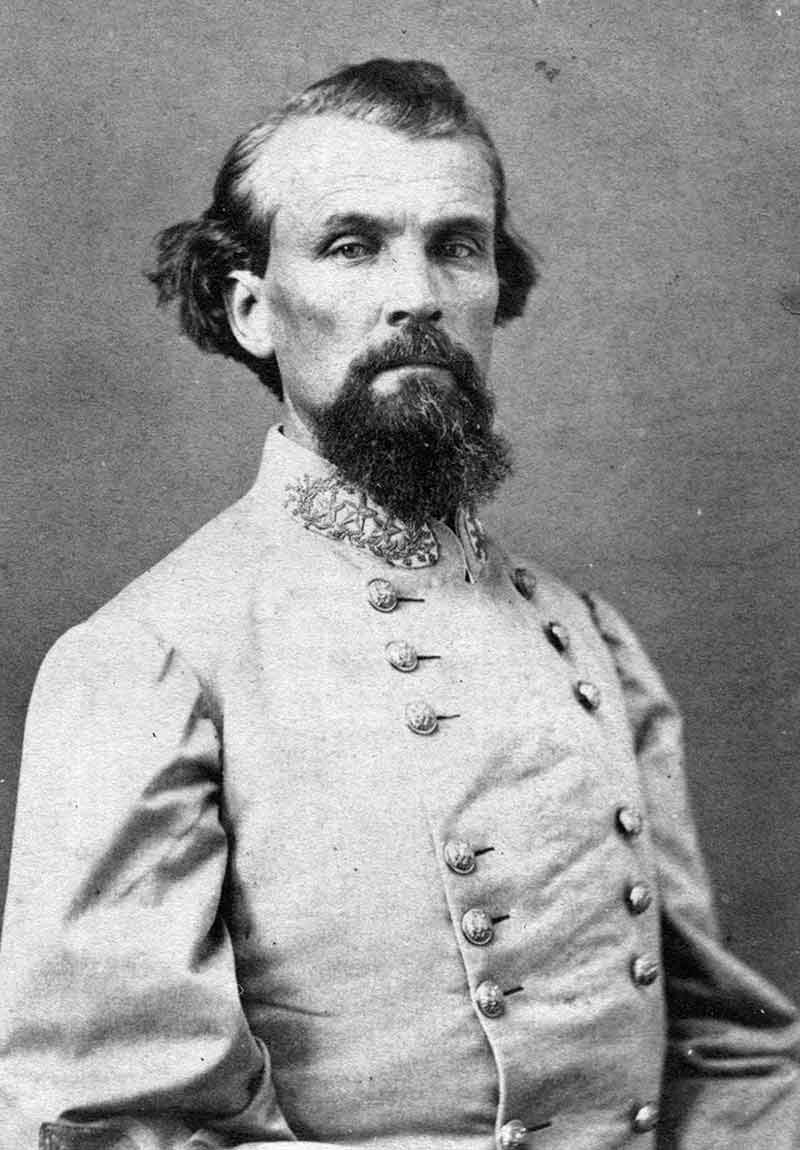

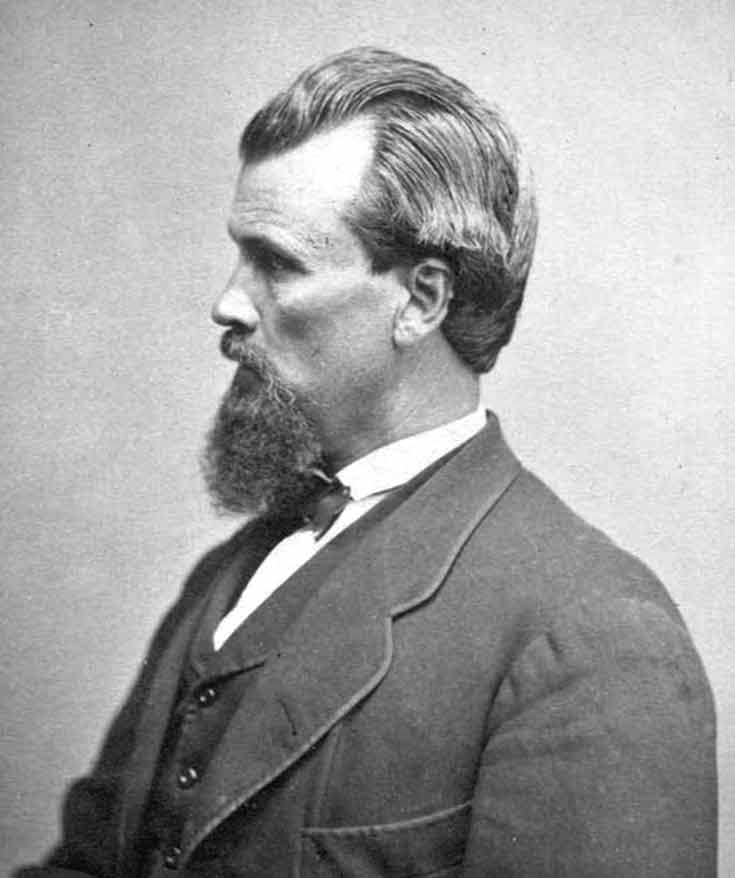

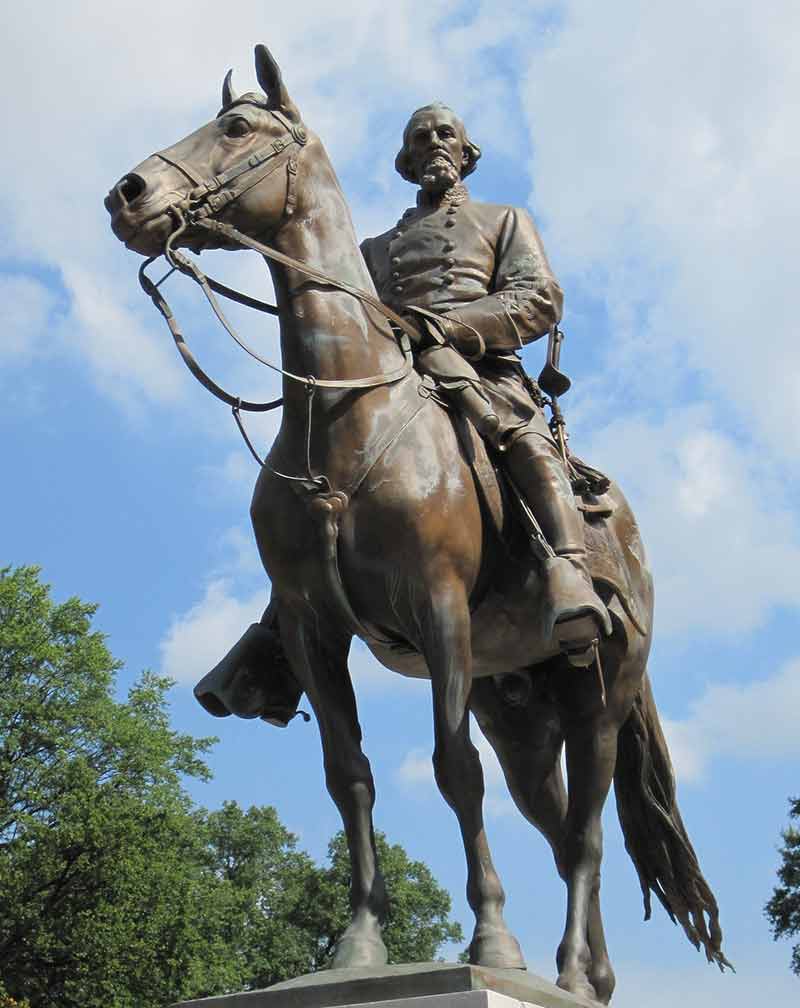

A short “war” ensued. To ensure a quick end to this revolt, Lincoln put General John Pope in charge of an expedition sent west for that purpose. Pope had distinguished himself earlier in 1862 by dealing harshly with the defenseless citizenry of the Shenandoah Valley, and he was encouraged to use the same tactics out west. Pope wrote a subordinate upon embarking for this new post,

“It is my purpose to utterly exterminate the Sioux…They are to be treated as maniacs or wild beasts, and by no means as people with whom treaties or compromises can be made.”

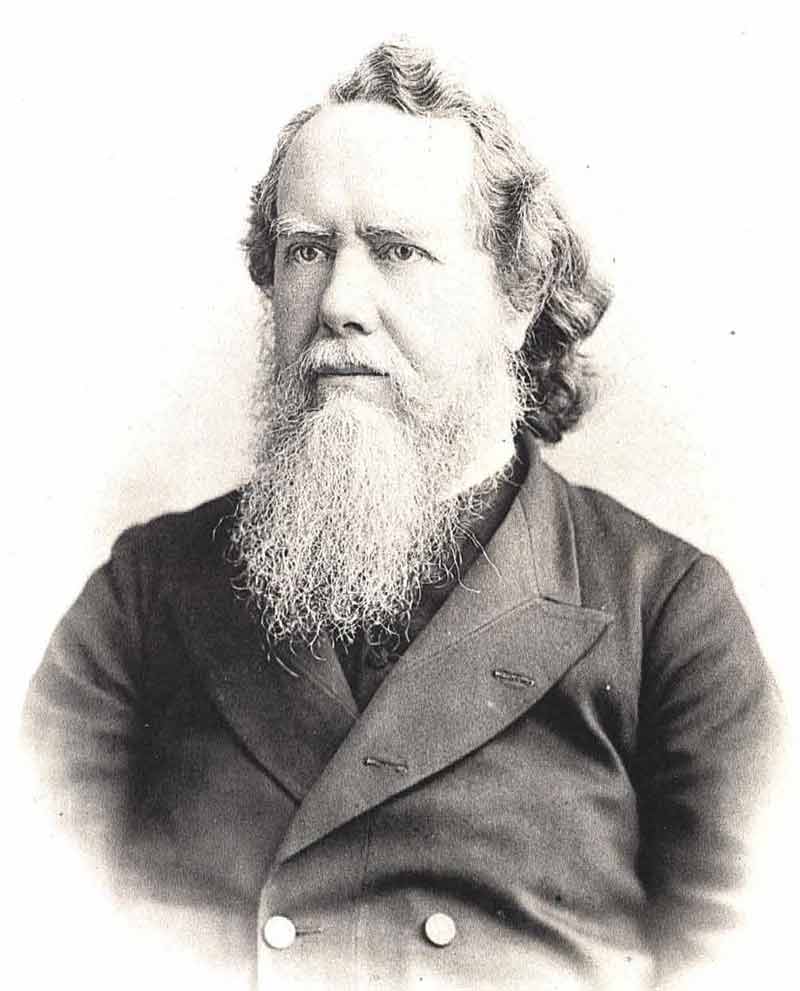

General John Pope (1822-1892), photographed 1860-65

Nevermind that it was his own government, and his Commander-in-Chief, President Lincoln, whose faithlessness had broken the treaty in the first place. Pope and his modernized army predictably overwhelmed the natives by October, 1862. The revolt thus put down, General Pope now held hundreds of “prisoners of war,” many of whom were native women and children who had been labeled as combatants for defending their homes.

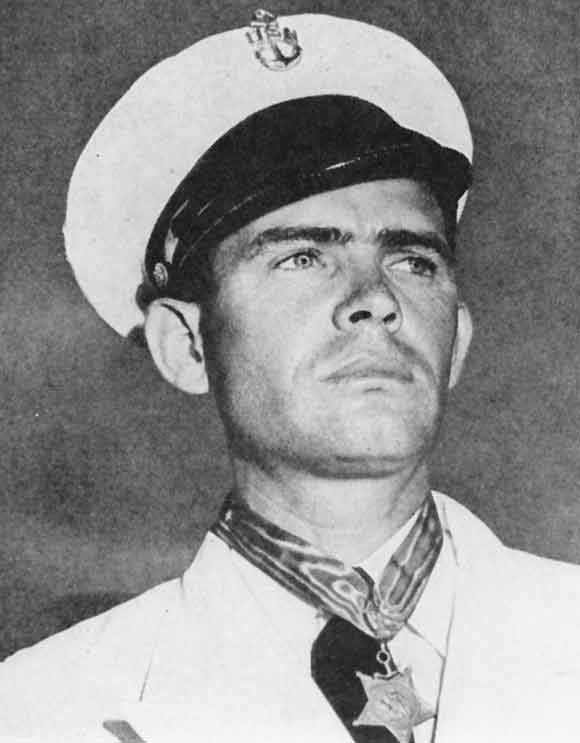

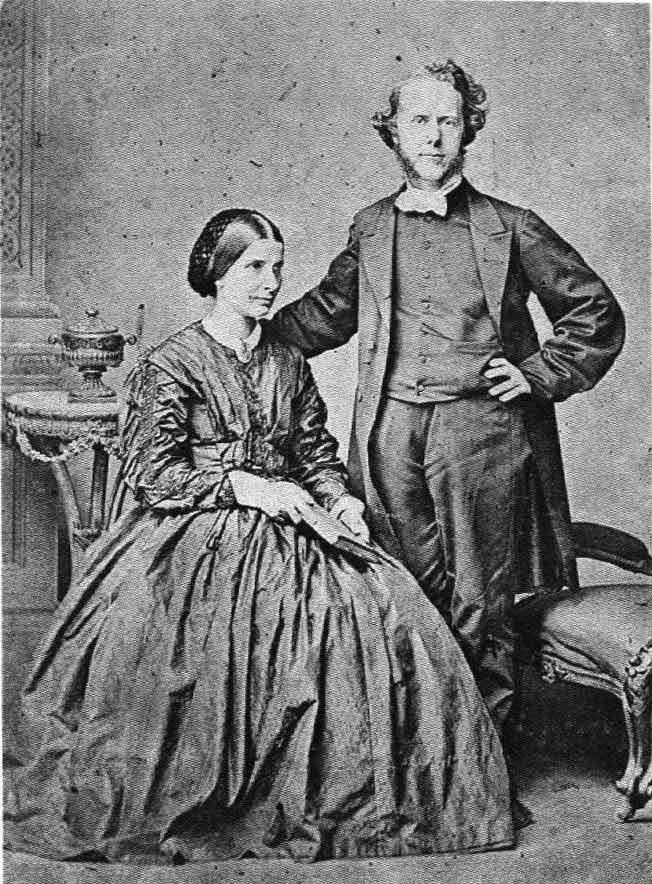

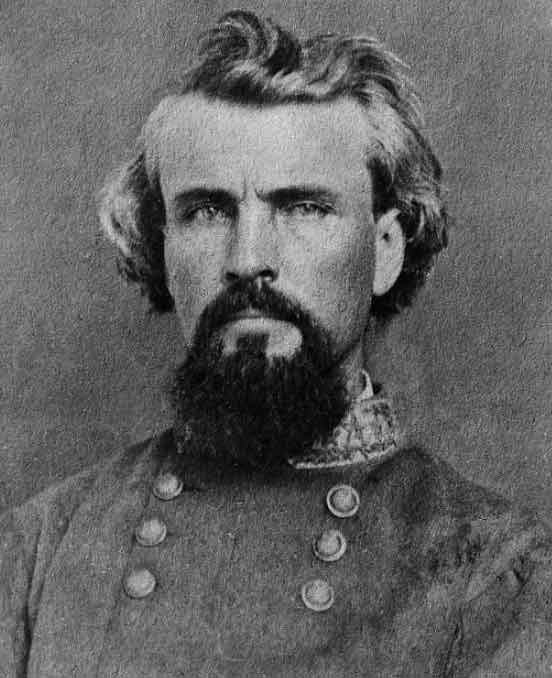

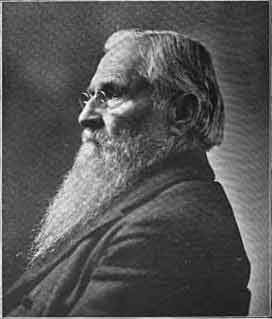

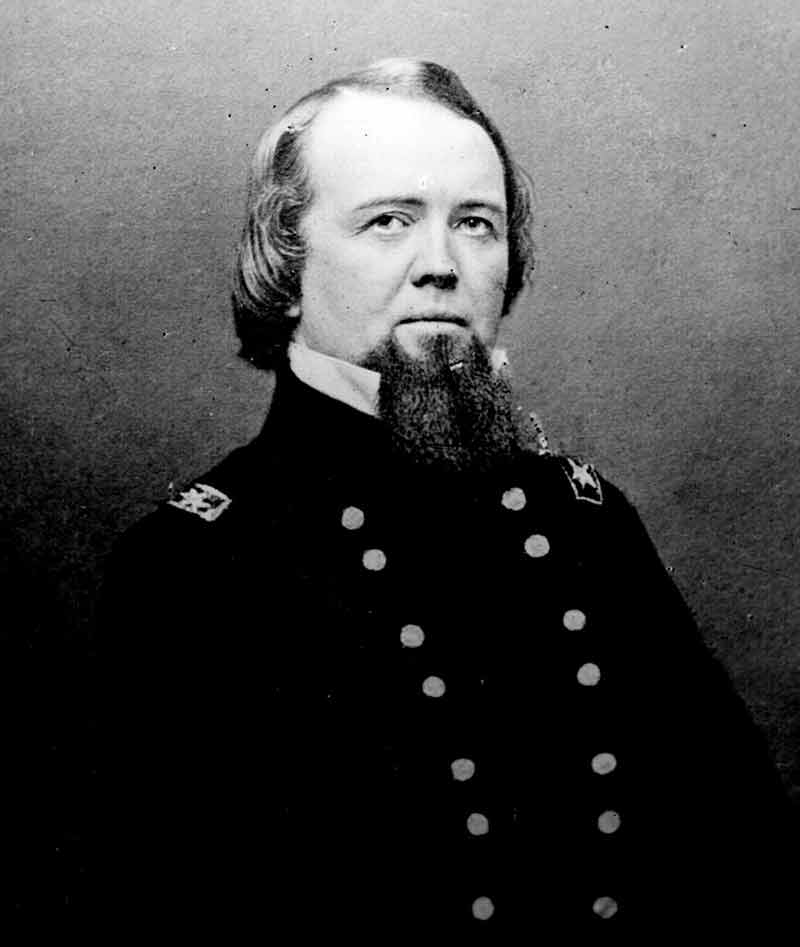

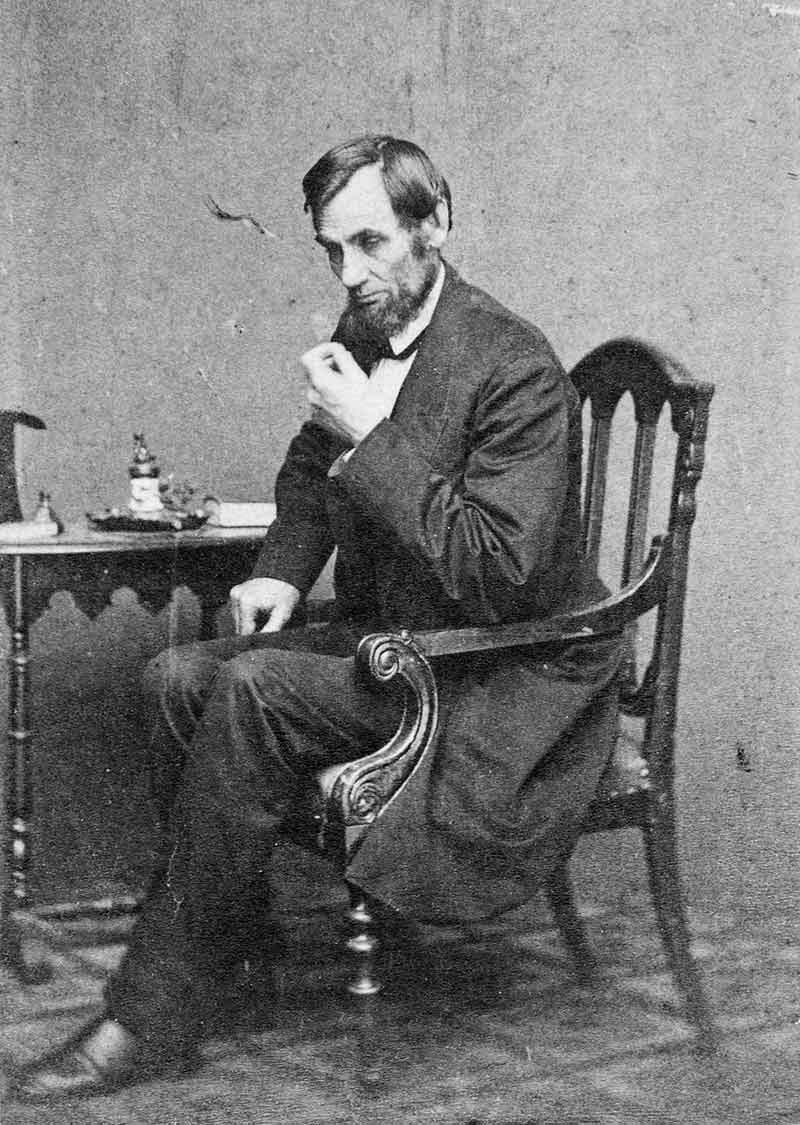

President Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865), photographed in 1862

These unfortunate souls were herded into military forts and there, over the course of a few months, military “trials” were held. Each trial lasted from five to fifteen minutes, conducted without an interpreter, without legal representation, and by a tribunal of officers who had in previous days been desecrating the homes of the accused. The lack of hard evidence, however, was manifest; many men were condemned just because they were present during a battle happening on their home turf.

In total, three hundred and three natives belonging to the Dakota tribe were sentenced to death for rising up against federal soldiers.

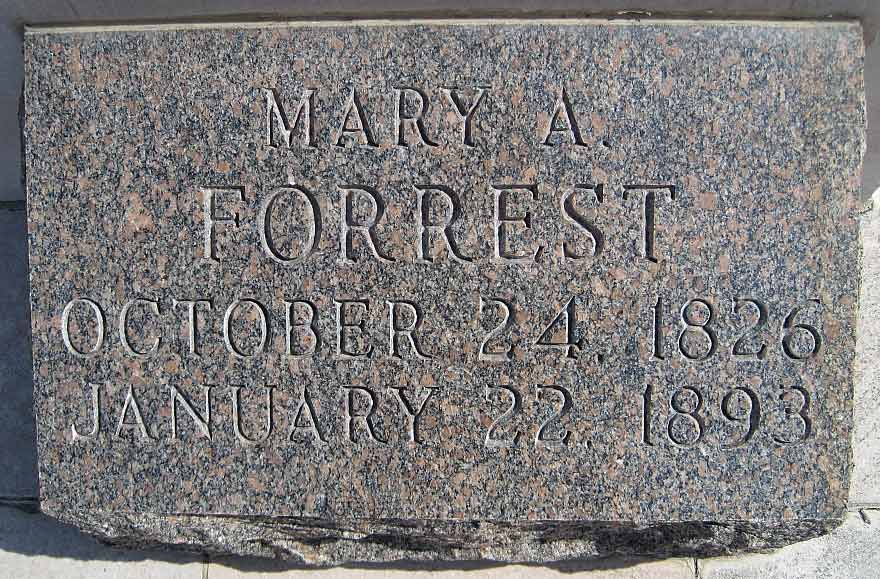

Sioux internment camp, Pike Island, winter 1862

When the transcripts of these proceedings reached Lincoln, he expressed fear that such a heavy-handed display of military justice might incite censure. He wrote,

“I ordered a careful examination of the records of the trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females.”

Only two men were found guilty of this, although how that was determined with the language barrier and lack of witnesses was not clear. The execution of two men was far too mild a response to satisfy the Minnesota government, on whose good graces Lincoln was heavily reliant for men and food to continue his war. As a result, Lincoln expanded this list of condemned men to thirty-nine, chosen for their supposed crimes against civilians. To sweeten this executive choice, Lincoln promised Minnesota’s politicians that in due course the Federal army would remove every last Indian from Minnesota—treaty or no. He kept that promise.

Fort Snelling, at the convergence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers, where nearly 2,000 Sioux were kept, awaiting “trial”

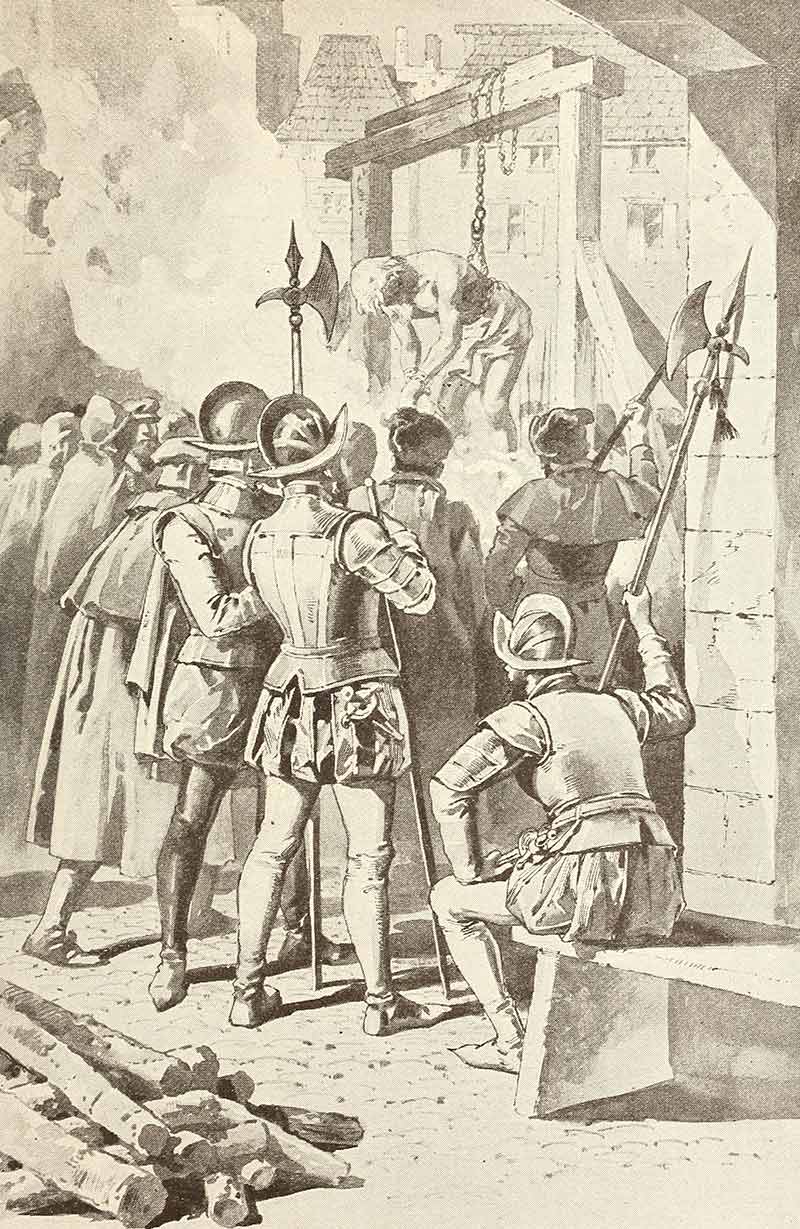

So it was that on December 26, 1862 President Lincoln’s hand-picked selection of thirty-eight men were executed by hanging, all at once, on a special scaffold made for the purpose. One had been pardoned last minute. An estimated 4,000 spectators crammed the streets of Mankato and the surrounding area to watch.

It remains the largest mass execution in American history—and yet the guilt of the executed was far from being determined beyond reasonable doubt.

The mass execution of 38 Sioux men in Mankato, Minnesota, December 26, 1862

According to historian Thomas DiLorenzo’s conclusions in his richly-cited book, The Real Lincoln:

“Lincoln would look bad if he allowed the execution of three hundred Indians, so he would execute only thirty-nine of them. But in return he would promise to have the Federal army murder or chase out of the state all the other Indians, in addition to sending the Minnesota treasury $2 million.”

Thus, the original violators of the treaty—the Minnesota government—would be payed with the money first promised to the Sioux Tribes in the broken treaty.

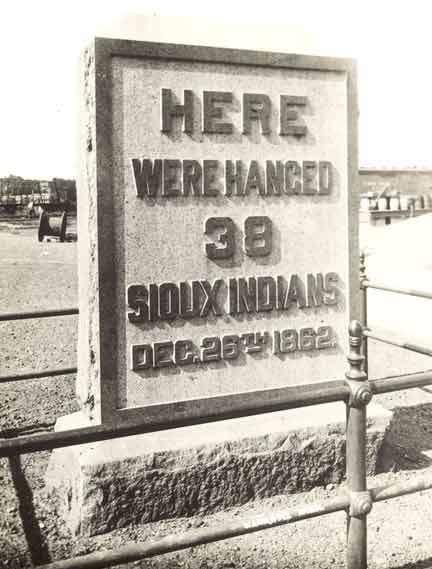

A memorial once stood to mark where the executions took place—it was removed in 1971

This tragic event remains a cautionary horror regarding the overreach of government, and how it is a cold and impersonal entity, bent by nature towards perpetuating injustices through any newfound might. Very often these powers are relinquished or bestowed by a fearful populace, eager for the promised benefits, blind to the impending tyranny. Oliver Cromwell once warned us,

“Necessity hath no law. Feigned necessities, imagined necessities… are the greatest [trickery]** that men can put upon the Providence of God, and make pretenses to break known rules by.”

*The “Sioux” Nation is a confederation of related tribes comprised of the Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota peoples, each speaking dialects of the Siouan language, with the Dakota being the easternmost group.

**original word used was “cozenage”, meaning trickery or deception

Image Credits: 1 Sioux Village (wikipedia.org) 2 Sioux Women (wikipedia.org) 3 1851 Treaty (wikipedia.org) 4 Sioux Revolt (wikipedia.org) 5 General John Pope (wikipedia.org) 6 President Abraham Lincoln (wikipedia.org) 7 Pike Island internment camp (wikipedia.org) 8 Fort Snelling (wikipedia.org) 9 Mass Execution (wikipedia.org) 10 Stone Marker (wikipedia.org)