The Aftermath of Knox’s Noble Train

Dear Reader, if you have not yet read last week’s essay on Henry Knox’s adventure, click here to read Mary Turley’s full account.

The Aftermath of Knox’s Noble Train

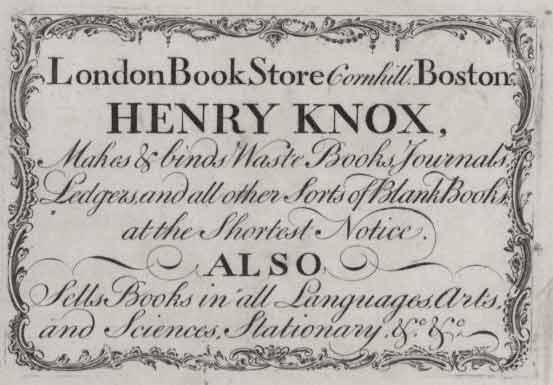

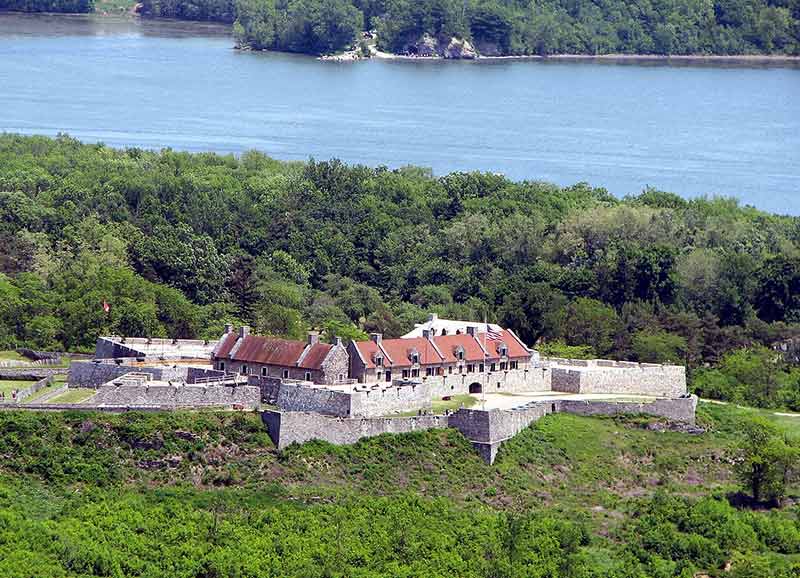

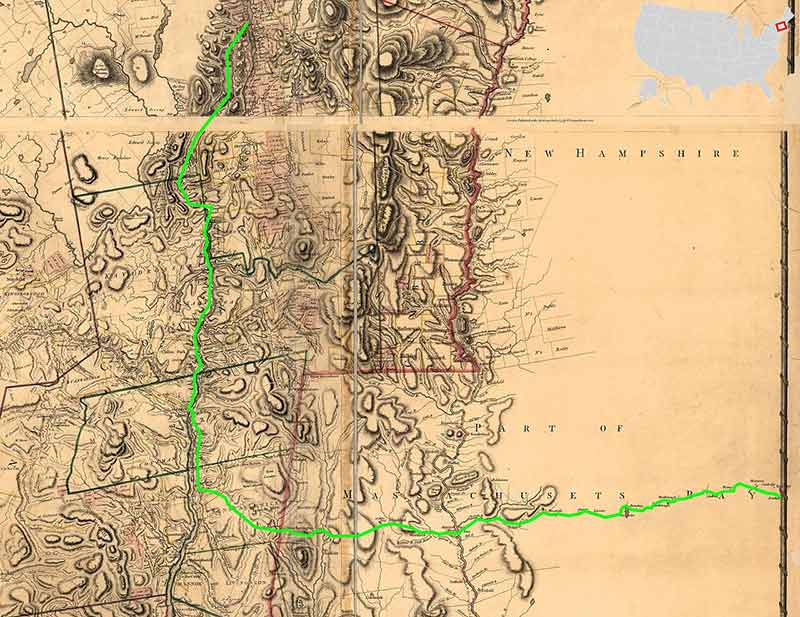

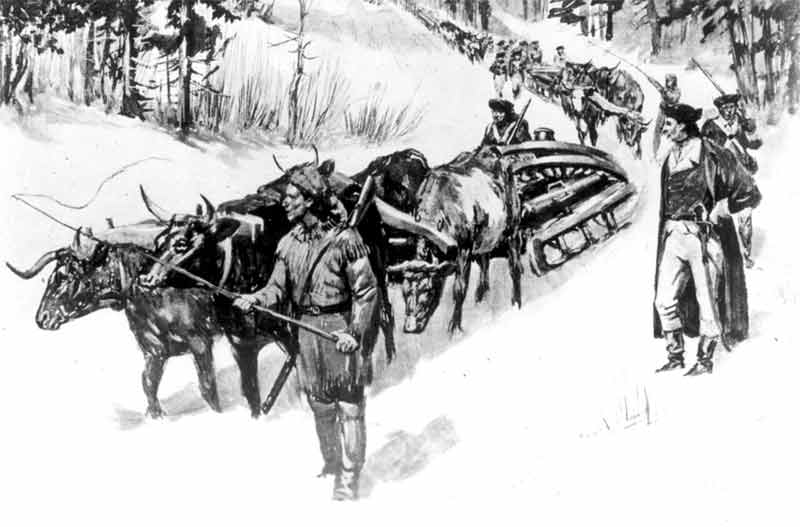

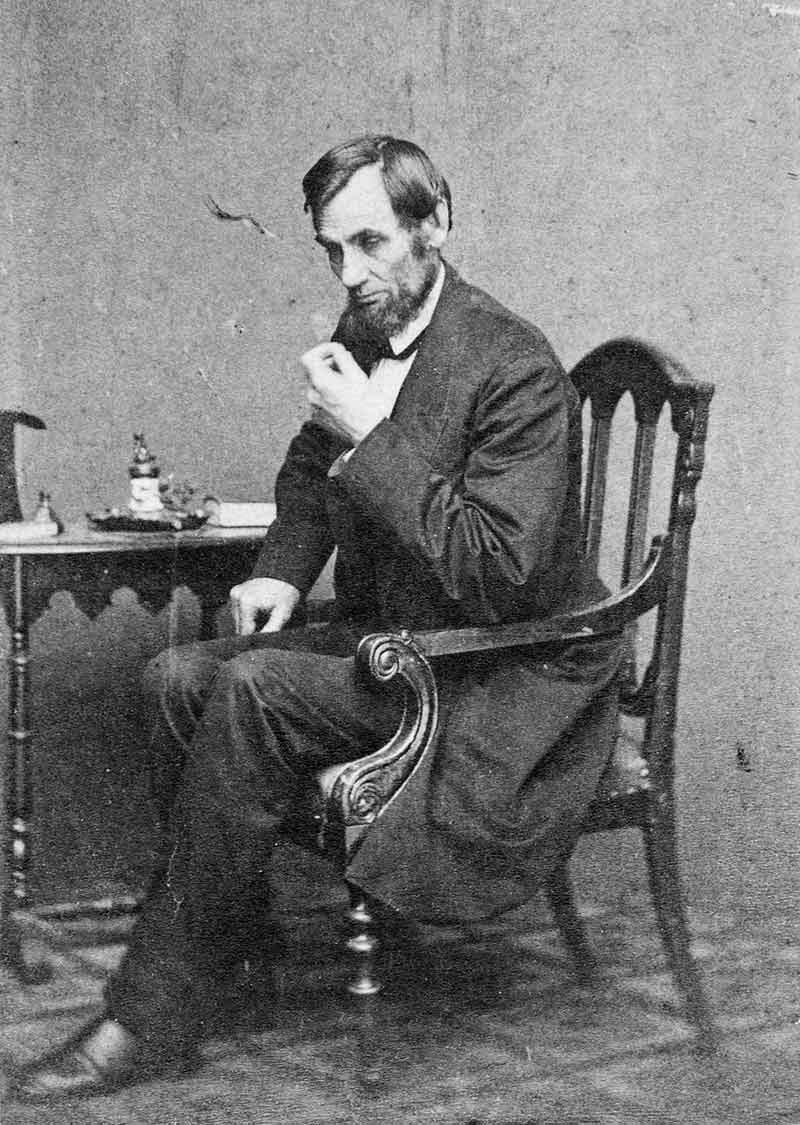

![]() ollowing Henry Knox’s prodigious feat in January 1776 of moving 60 plus abandoned cannon for the patriot cause over 400 miles of treacherous terrain for the relief of Boston, several notable characters commented on the mission’s success. One such was British military commander, General William Howe. Upon waking one day, Howe found Dorchester Heights around Boston bristling with patriot cannon, their muzzles bearing down on his position, their threat having materialized overnight. He is said to have exclaimed, “My God, these fellows have done more work in one night than I could make my army do in three months.”

ollowing Henry Knox’s prodigious feat in January 1776 of moving 60 plus abandoned cannon for the patriot cause over 400 miles of treacherous terrain for the relief of Boston, several notable characters commented on the mission’s success. One such was British military commander, General William Howe. Upon waking one day, Howe found Dorchester Heights around Boston bristling with patriot cannon, their muzzles bearing down on his position, their threat having materialized overnight. He is said to have exclaimed, “My God, these fellows have done more work in one night than I could make my army do in three months.”

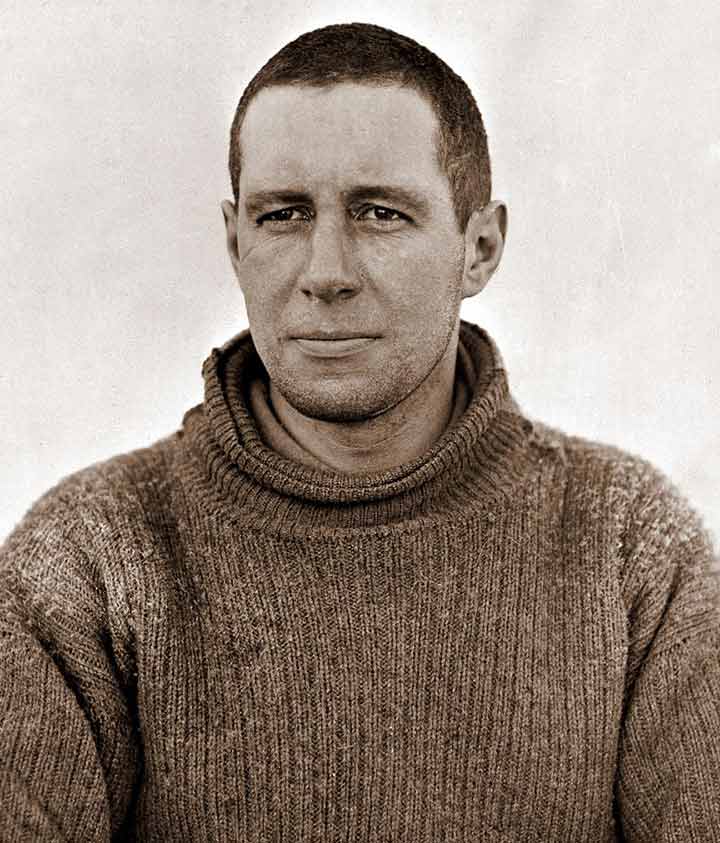

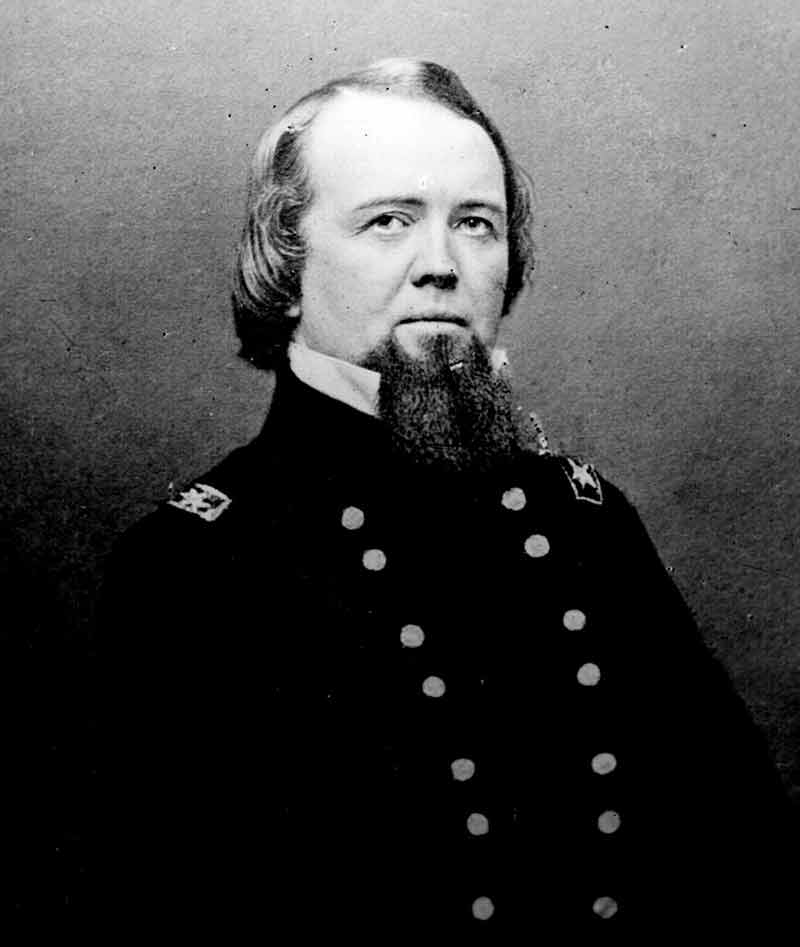

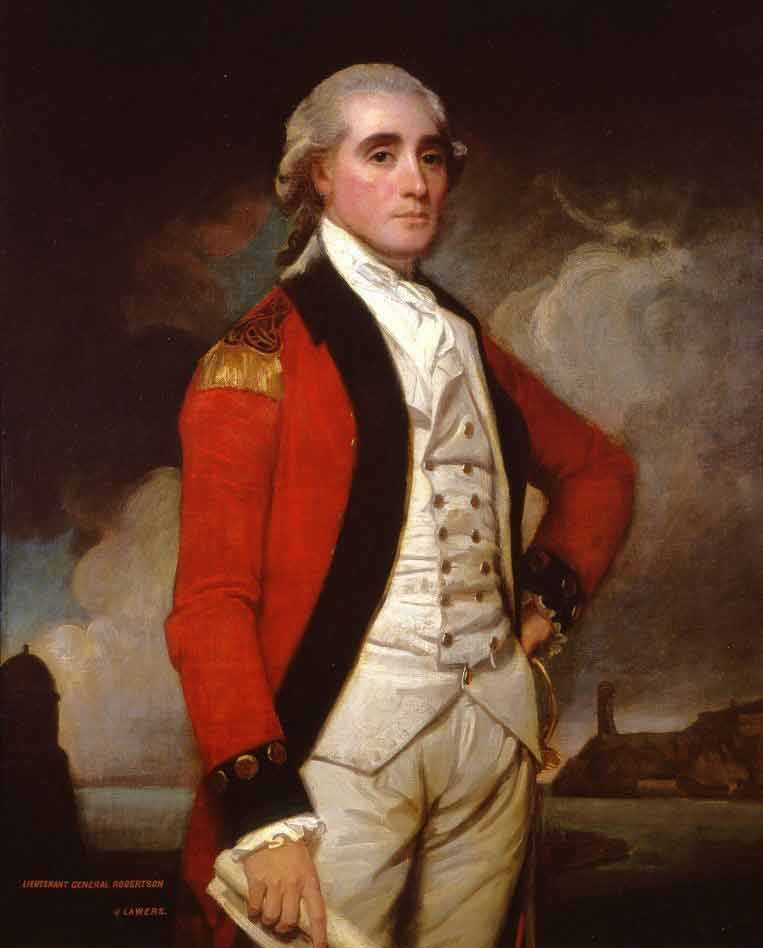

General William Howe (1729-1814)

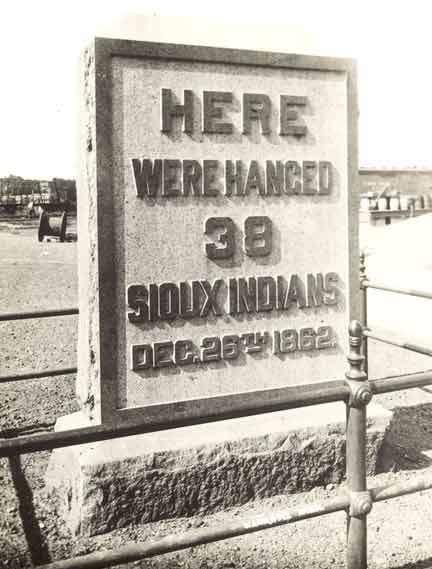

The chief British engineering officer, Archibald Robertson, calculated that to have carried everything into place as the rebels had—“a most astonishing night’s work”—must have required at least 15,000 to 20,000 men. The true number was closer to 3,000.

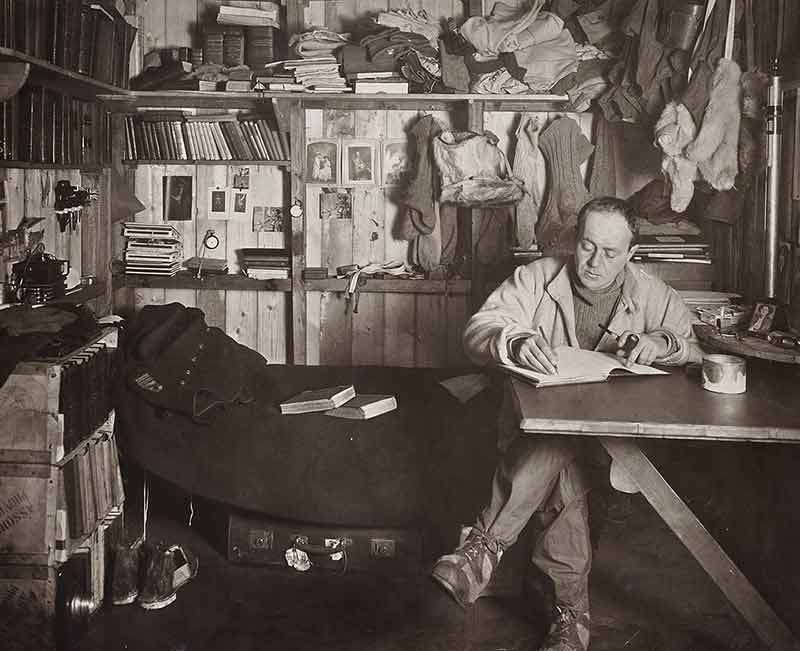

Major Archibald Robertson (1745-1813)

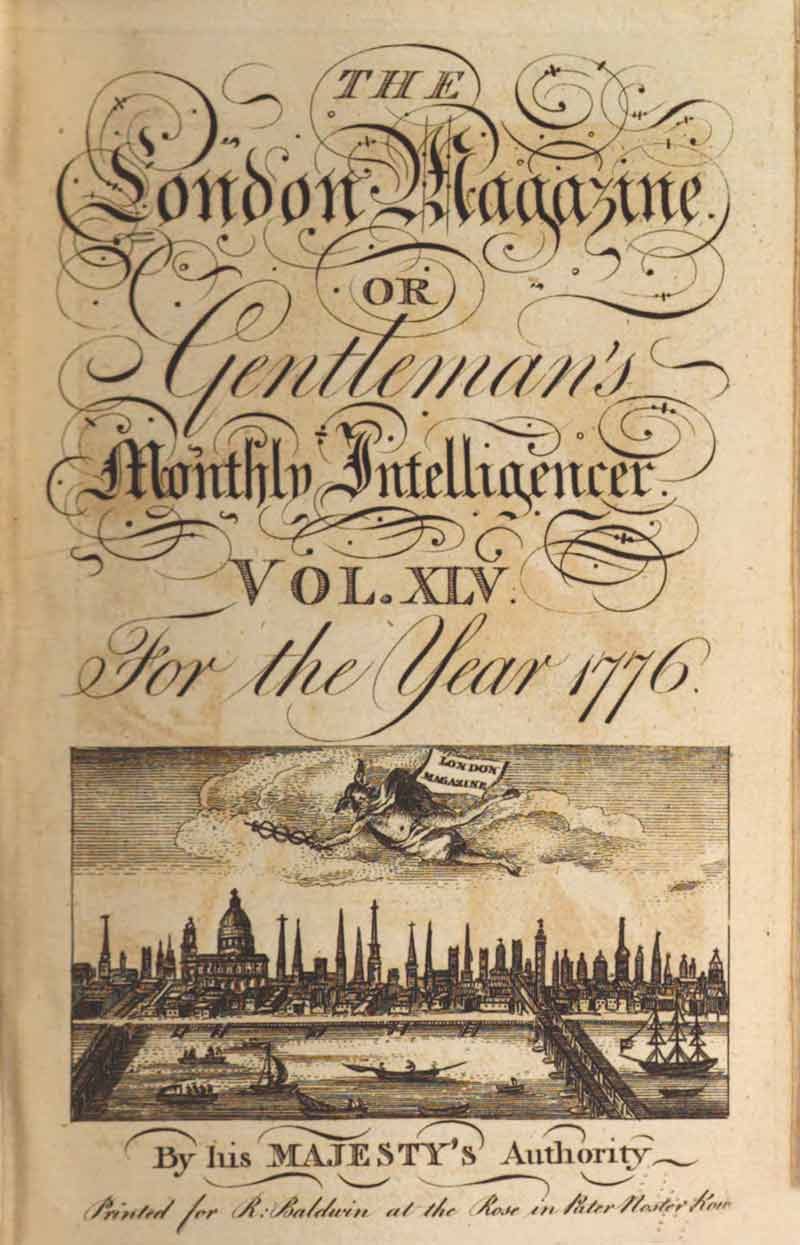

Later that spring, one of the London papers would carry portions of a letter attributed to an unnamed “officer of distinction” at Boston who summed it up as:

“They [the fortifications] were all raised during the night, with an expedition equal to that of the genie belonging to Aladdin’s wonderful lamp. From these hills they command the whole town, so that we must drive them from their post, or desert the place.”

The British evacuated Boston on March 17, 1776 without a fight.

We bring you these sober reminders in the duty of thanksgiving for all good gifts bestowed from above during this 250th year anniversary of the founding of America. These acts of gratitude to Almighty God are required—the recounting of the many instances of God’s Mighty Hand in the establishment our great nation. Prayer, both national and individual, bathed this struggle, and the resultant miracles attendant upon it were due entirely to this great reliance upon the Divine Disposer of all things.

Give ear, O my people, to my teaching;

incline your ears to the words of my mouth!

I will open my mouth in a parable;

I will utter dark sayings from of old,

things that we have heard and known,

that our fathers have told us.

We will not hide them from their children,

but tell to the coming generation

the glorious deeds of the LORD, and his might,

and the wonders that he has done.

—Psalm 78:1-4