Carrie McGavock — An American Heroine

Heroism and self-sacrifice are often exhibited in battle, but it was in the aftermath of the battle of Franklin, Tennessee that one woman’s selflessness became legendary. The impression of Carrie McGavock’s unflinching kindness and the services she rendered lingered long in the memory of both those she served and the entire South.

Heroism and self-sacrifice are often exhibited in battle, but it was in the aftermath of the battle of Franklin, Tennessee that one woman’s selflessness became legendary. The impression of Carrie McGavock’s unflinching kindness and the services she rendered lingered long in the memory of both those she served and the entire South.

The number of wounded that were left behind after the battle to be cared for by the citizens of that small town was staggering. The homes of overwhelmed civilians were crowded to overflowing with Confederate soldiers, hastily attended to by too few doctors equipped with inadequate supplies.

Carnton Plantation and the McGavock Confederate Cemetery

The largest of these field-hospitals was Carnton Plantation, the home of Carrie McGavock. This young mother’s tireless efforts to comfort and calm the soldiers whose shattered bodies filled her home were never forgotten by them.

Accounts written by the survivors of that horrible time are full of gratitude and reverence for the woman who cared for them as if they were her own.

Carrie McGavock

The last of these wounded men would not leave her home until the following year. By that time, Carrie McGavock and her husband, John had taken upon themselves yet another momentous duty.

Offering a portion of their own land, the McGavocks initiated and oversaw the identifying and reinterring of nearly 1,500 Confederate soldiers previously buried in mass graves.

Carrie McGavock was committed to identifying and honoring these brave men whose relations had previously been in ignorance of their fate. In a ponderous ledger, she meticulously recorded their names, possessions and final places of burial.

From 1866 until her death in 1905, she cheerfully welcomed a flood of visitors who came in hopes of finding the grave of a loved one they had not heard of since before the battle. Her dedication to preserving the memory of these fallen sons of the Confederacy earned her the nickname “The Widow of the South.”

The Civil War in the West tour is one of the most interesting and inspiring tours we host, full of remarkable providences and colorful characters including Private Tod Carter, John Bell Hood, Patrick Cleburne and many others. Come walk the battlefields and tour the homes that still bear the marks of war with Landmark Events historian Bill Potter and Sam Turley March 16-17 in Franklin and Nashville, TN.

What a sight it must have been for 24-year-old Captain Tod Carter as he stood near Winstead Hill facing north toward his boyhood home, just over a mile away. It was late November of 1864 and Young Tod had not seen his home since that bitter war began.

What a sight it must have been for 24-year-old Captain Tod Carter as he stood near Winstead Hill facing north toward his boyhood home, just over a mile away. It was late November of 1864 and Young Tod had not seen his home since that bitter war began.

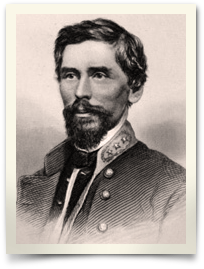

“If we are going to die, then let us die like men.” These were the last recorded words of General Patrick R. Cleburne, uttered to his men at the battle of Franklin shortly before advancing his division forward into the jaws of death.

“If we are going to die, then let us die like men.” These were the last recorded words of General Patrick R. Cleburne, uttered to his men at the battle of Franklin shortly before advancing his division forward into the jaws of death.