The Christmas Truce, 1914

“And he shall judge among the nations, and shall rebuke many people: and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.”—Isaiah 2:4

The Christmas Truce, December 25, 1914

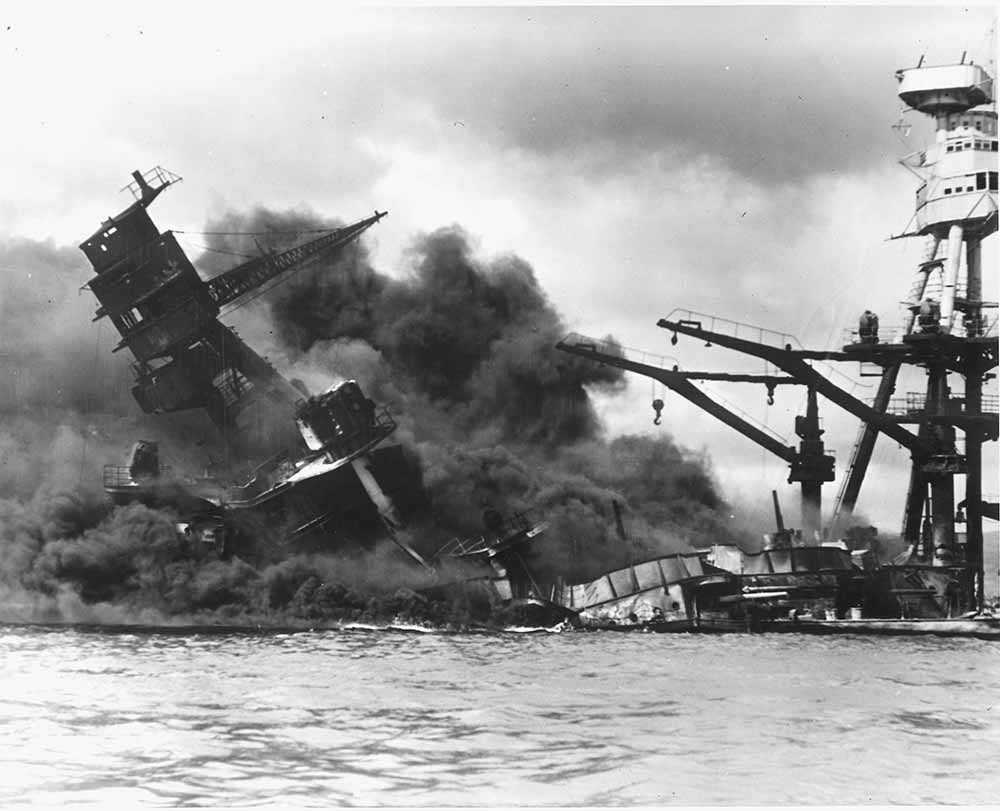

ntering 2024, we will soon mark the 110th anniversary of the commencement of the First World War—“the war to end all wars”. In 1914 the nations of Europe collectively produced the greatest human catastrophe in the history of Western Civilization, the causes of which are still debated to this day. In four years of war, about eleven million men died on the battlefield and twenty million were wounded, many of whom later died of wounds. More than seven million civilians died in the war. Improved machine gun and artillery technology created battlefields in which killing proceeded on an industrial scale. The bereavement and sorrow that accompanied this unnecessary tragedy still resonates today, especially in Great Britain, Australia, and Canada.

ntering 2024, we will soon mark the 110th anniversary of the commencement of the First World War—“the war to end all wars”. In 1914 the nations of Europe collectively produced the greatest human catastrophe in the history of Western Civilization, the causes of which are still debated to this day. In four years of war, about eleven million men died on the battlefield and twenty million were wounded, many of whom later died of wounds. More than seven million civilians died in the war. Improved machine gun and artillery technology created battlefields in which killing proceeded on an industrial scale. The bereavement and sorrow that accompanied this unnecessary tragedy still resonates today, especially in Great Britain, Australia, and Canada.

British and German troops meet in no-man’s-land during the unofficial truce

The Christmas Truce on the Western Front, 1914

The repercussions of the war among “intellectuals” and purveyors of cultural mores in Europe, reflected in their art and philosophies a wholesale abandonment of biblical ethics, moral restraints, and hope in the future. An unrestrained moral turpitude and relativism, born in the evolutionary theories of the previous century, reached their climax in the post-war era. They quickly sifted down to popular culture and produced equally unrestrained offshoots of reaction and nationalistic paganisms represented in the Fascists of Italy and Nazis of Germany, not to speak of the revolutionary excesses of the Bolsheviks in Russia. In modern parlance, The First World War was the tipping point of world-wide change, and not for the better.

On December 25, 1914, with the British and German troops facing each other in their respective trenches across the frozen wastes of no-man’s-land—over which both sides had already shed much blood—a remarkable phenomenon occurred about which entire books have been written. Almost spontaneously, men on both sides began singing Christmas carols. Men so determined the day before to exterminate each other, probably for the last time in all of their lives, commemorated the birth of Christ in music. On the German side, men wore belt buckles stamped “Gott mit uns” (God with us), believing that they were on the side of right. On the English side, numbers of men came from Christian homes, and remembered the carols of safe and warm family celebrations where they sang hymns composed by German and English writers.

Unbelievably, several men climbed out of the trenches with hands up, from both sides, and met in no-man’s-land. Someone kicked out a soccer ball and they formed teams and played. Others exchanged souvenirs and talked about home and families. A few years ago, Sainsbury’s grocery chain in England memorialized that famous Christmas truce with this ad:

When the generals heard about the fraternization with the enemy going on all along the entrenchments, they called a halt to it and ordered the war to resume. Some believe up to a hundred thousand men participated in the informal truce of Christmas 1914.

In the early months of the war, the two sides sometimes agreed to bury bodies, otherwise irretrievably lying between the lines. This event was different—widespread and visually stunning, many men wrote home about it, from both sides. The Christmas truce provided a small shred of humanity in a war that would abandon any pretense of it in the coming years. Not only did that war not end wars, it provided the reason and impetus for a bigger and more destructive one twenty-one years later.

British and German soldiers play a soccer game during the truce

An artist’s impression of the truce from The Illustrated London News

Man has sought to find a solution to war through institutions like the League of Nations and the United Nations, treaties, policies like “Mutually Assured Destruction” (MAD), and legislation. No attempts at eradicating the sins of men and nations nor ending their never-ending pursuit of war through government action can or will succeed without the true salvation and peace of Christ in the hearts of leaders and people. God promises that He will bring about His peace in history future when His kingdom shall extend from shore to shore around the world. All Christians should pray to that end; every other kind of peaceful resolution is just another Christmas truce.

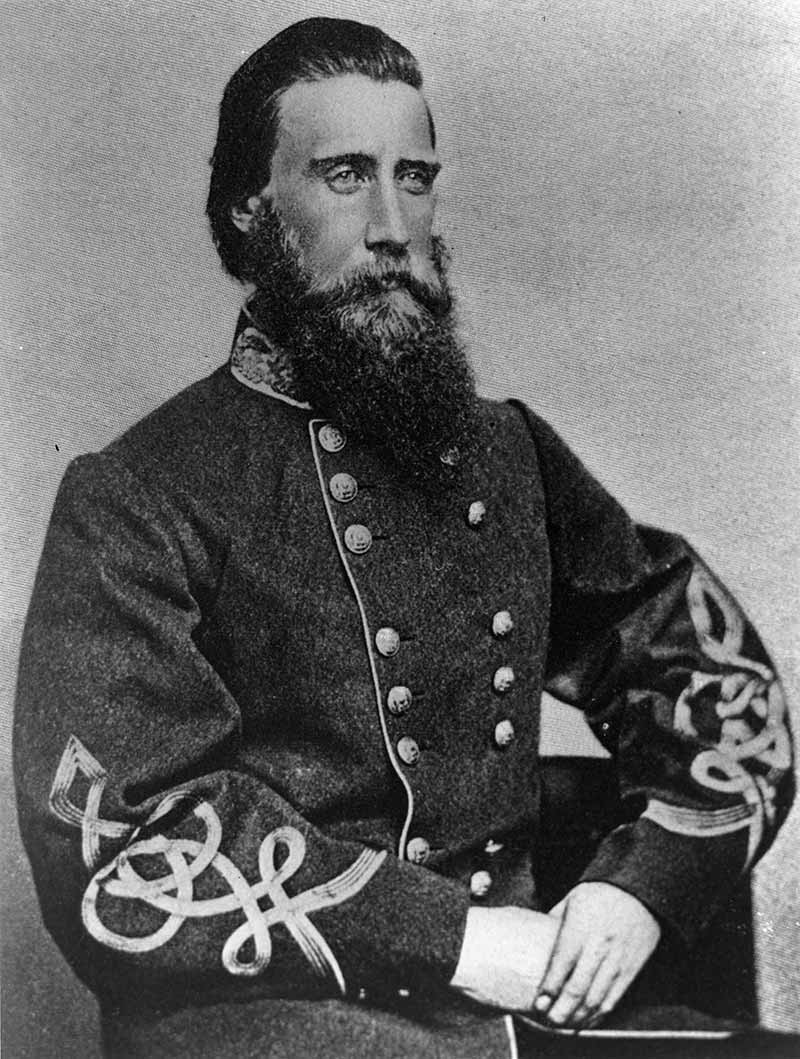

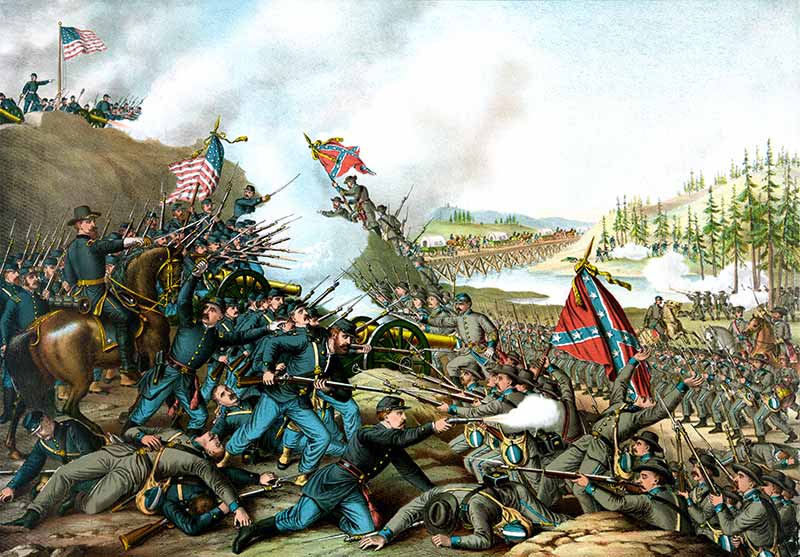

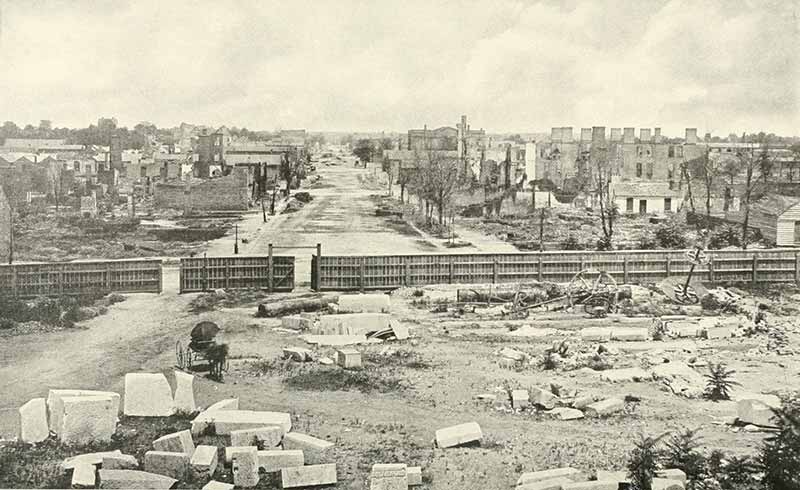

n a late Indian Summer’s day, the crippled Confederacy gave its last valiant gasp when 33,000 brave southern men and boys charged the Union Army’s entrenchments amongst the homes and businesses of Franklin, Tennessee. The last grand frontal assault of America’s Civil War, these men charged over two miles of open ground, in perfect order, with bands playing and flags unfurled, in the face of a hailstorm of bullets. The tactics of the assault were questioned by the majority of the Confederate Army’s own commanders, but having been decided upon by their superior—General John Bell Hood—there was never a braver or more ferocious fight to liberate what was the beloved hometown of many in the Army of the Tennessee.

n a late Indian Summer’s day, the crippled Confederacy gave its last valiant gasp when 33,000 brave southern men and boys charged the Union Army’s entrenchments amongst the homes and businesses of Franklin, Tennessee. The last grand frontal assault of America’s Civil War, these men charged over two miles of open ground, in perfect order, with bands playing and flags unfurled, in the face of a hailstorm of bullets. The tactics of the assault were questioned by the majority of the Confederate Army’s own commanders, but having been decided upon by their superior—General John Bell Hood—there was never a braver or more ferocious fight to liberate what was the beloved hometown of many in the Army of the Tennessee.

ohammed, the founder and prophet of Islam, and his successors, spread their new religion across the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia beginning in the 7th Century, through conquest, commerce, and missionaries. Those who did not convert, particularly Christians and Jews, were compelled to pay extra taxes, and bid to comply with the new cultural changes. They established new Muslim dynasties in the areas conquered, including in Palestine, where many of the historic sites from the time of Christ and the apostles were located. Christian pilgrims who travelled to those places were sometimes set upon by thieves and lawless gangs, and the Christians and Jews of those areas faced the constant pressure to convert to Islam. Moslem structures were sometimes constructed over the older Christian ones. The Roman Pontiffs began calling for the re-conquest of the Middle East, from the 11th to the 14th Centuries.

ohammed, the founder and prophet of Islam, and his successors, spread their new religion across the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia beginning in the 7th Century, through conquest, commerce, and missionaries. Those who did not convert, particularly Christians and Jews, were compelled to pay extra taxes, and bid to comply with the new cultural changes. They established new Muslim dynasties in the areas conquered, including in Palestine, where many of the historic sites from the time of Christ and the apostles were located. Christian pilgrims who travelled to those places were sometimes set upon by thieves and lawless gangs, and the Christians and Jews of those areas faced the constant pressure to convert to Islam. Moslem structures were sometimes constructed over the older Christian ones. The Roman Pontiffs began calling for the re-conquest of the Middle East, from the 11th to the 14th Centuries.