“Deus Vult!”

The Knights Templar Destroyed, November 22, 1307

ohammed, the founder and prophet of Islam, and his successors, spread their new religion across the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia beginning in the 7th Century, through conquest, commerce, and missionaries. Those who did not convert, particularly Christians and Jews, were compelled to pay extra taxes, and bid to comply with the new cultural changes. They established new Muslim dynasties in the areas conquered, including in Palestine, where many of the historic sites from the time of Christ and the apostles were located. Christian pilgrims who travelled to those places were sometimes set upon by thieves and lawless gangs, and the Christians and Jews of those areas faced the constant pressure to convert to Islam. Moslem structures were sometimes constructed over the older Christian ones. The Roman Pontiffs began calling for the re-conquest of the Middle East, from the 11th to the 14th Centuries.

ohammed, the founder and prophet of Islam, and his successors, spread their new religion across the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia beginning in the 7th Century, through conquest, commerce, and missionaries. Those who did not convert, particularly Christians and Jews, were compelled to pay extra taxes, and bid to comply with the new cultural changes. They established new Muslim dynasties in the areas conquered, including in Palestine, where many of the historic sites from the time of Christ and the apostles were located. Christian pilgrims who travelled to those places were sometimes set upon by thieves and lawless gangs, and the Christians and Jews of those areas faced the constant pressure to convert to Islam. Moslem structures were sometimes constructed over the older Christian ones. The Roman Pontiffs began calling for the re-conquest of the Middle East, from the 11th to the 14th Centuries.

A panoramic view of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, as seen from the Mount of Olives

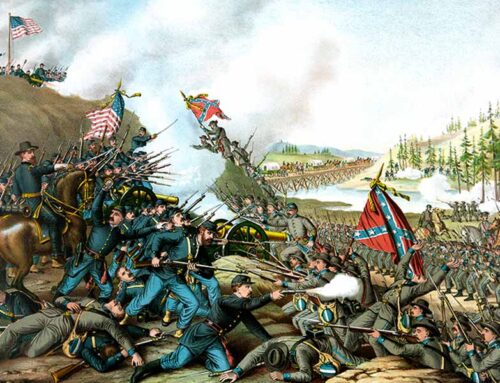

Kings, princes and monks raised armies in Europe, especially France, to make the long journey to the Holy Land to drive out the Muslim interlopers. The Latin Church granted them forgiveness and indulgence, the nobility called on the feudal obligations of their vassals to go to war, and Kings took up their positions at the head of armies, all with the commendation and approval of the Pope in Rome. The success of the First Crusade, with the capture of Jerusalem in 1099, however, did not eliminate the dangers that awaited Christian pilgrims, who had to walk or ride from Joppa to Jerusalem. Death came to hundreds of European pilgrims from thieves and terrorists who stalked the byways leading to the city.

King Baldwin II of Jerusalem ceding the location of the Temple of Solomon to Hugues de Payns and Gaudefroy de Saint-Homer in the presence of Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem

In 1119, nine knights banded together and petitioned Baldwin II, King of Jerusalem and Warmund, the Patriarch of the region, to allow them to create a new warrior-monastic order to protect the pilgrims coming to the Holy City. Their petition was granted and the Knights were given part of the Al Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem for their headquarters.

The Temple Mount in Jerusalem, showing Al Aqsa Mosque (once headquarters of the Knights Templar) prominently in the center with the gold dome

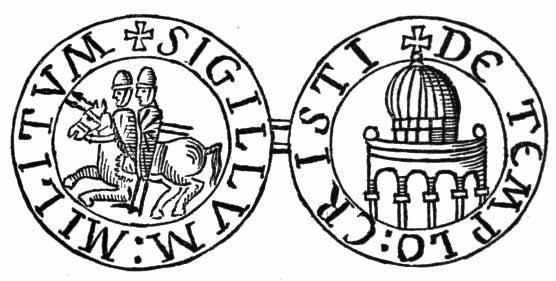

The first knights were poor men, relying on donations to keep their horses and themselves in shape for the hazards that lay in wait. Their initial moniker consisted of two knights riding one horse. Their official name began as “Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon,” fortunately shortened to Knights Templar. One of the founding Templars was André de Montbard, the uncle of one of the most influential monks of Christendom, Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, founder of the Cistercian Order, hymn writer, and powerful preacher. In 1129 Bernard convinced a Church Council to approval the Knights, resulting in large contributions, new recruits, and a Templar fighting force to be reckoned with.

The Seal of the Knights Templar, showing two knights riding one horse

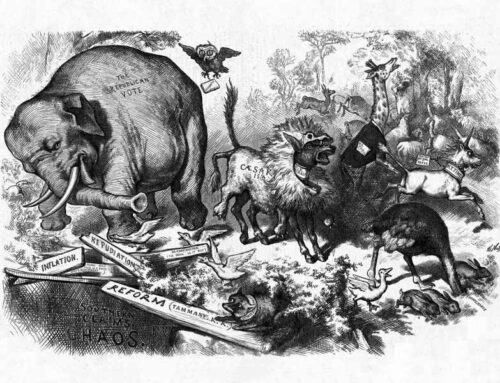

On March 31, 1146—with King Louis VII of France present—Bernard of Clairvaux preached to an enormous crowd in a field at Vézelay, making “the speech of his life”

The Popes declared that the Templars could pass through any lands, exempted from taxes and local laws, and answerable to the Pope alone. Mounted on their huge destriers, wearing the finest armor and confident in their cause, the Knights led Crusader attacks wearing their white tunics with the red cross on the front and bearing their banners so the enemy would know who they were up against. In one battle, five hundred knights and a few thousand foot soldiers defeated a 26,000-man army led by Saladin himself, the most feared of the Moslem chiefs.

Represented by Guy of Lusignan, members of the Knights Templar (in their classic white robes with red crosses) surrender to Saladin after their defeat at the Battle of Hattin

While the knights of the order took individual vows of poverty, and most of them just provided logistical help for the fighters, the Templars accumulated vast treasures put in their care by crusader nobles along with donations from wealthy supporters and the Church. Their financial services became an early form of banking. The Knights Templar built castles and cathedrals and acquired vast tracts of land in Europe and the Middle East, becoming a form of multi-national corporation. They inspired the creation of other warrior orders, the Teutonic Knights from the Germanies and the Knights of St. John, known as the Hospitallers, devoted to both the healing arts and ferocious warriors of the Church.

Hugues de Payens (1070-1136) was the co-founder and first Grand Master of the Knights Templar. In association with Bernard of Clairvaux, he created the Latin Rule, the code of behavior for the Order.

Krak des Chevaliers in Syria was built during the 12th and 13th centuries by the Knights Hospitaller with later additions by Mamluks

In the mid-12th Century, Crusader fortunes waned as strong Islamic leaders like Saladin found strategies to defeat the Latin armies. The military orders became sometimes bitter rivals, thus dividing the loyalties within the Crusader ranks. They lost Jerusalem in 1187, retook it in 1229 and surrendered the city in 1239, where it remained under Muslim control until the British seized it in 1917 from the Ottoman Turks. Templar headquarters moved to Acre, which they held for a hundred years before yielding to relentless attacks, pushing them to Cyprus. After two hundred years of fighting, the Templars settled down to international businesses, farming, and vineyards.

Philip IV of France (1268-1314)

Pope Clement V (c. 1264-1314)

In 1307, King Philip IV of France (deeply in debt to the Templars) and Pope Clement V (eager to put an end to the order) colluded together to destroy the Templars. On November 22, Clement issued a papal bull ordering the disbandment of the Knights Templar, and calling for their arrests and the seizure of their properties. Following their arrests, they were put on trial for crimes that historians conclude never occurred, based on the best evidence. Besides charges of financial corruption, the Templars were accused of spitting on the cross of Christ, blasphemy, and idolatry. Torture and coerced confessions confirmed the charges, though they all recanted their confessions once the torture was finished. In the end, de Molay and many Templars were burned at the stake, others were pensioned off, or joined other orders. Many of their assets were transferred to the Hospitallers. Some believe there still exists a vast treasure trove of hidden Templar wealth. There are all sorts of reported sightings of Templars in the years following their disbandment, such as joining Scottish armies in battle in Scotland against the English. Templar architecture remains intact in several countries, including Portugal, Spain, and England. The mystique of the Knights Templar still excites historians of the Middle Ages and of the Crusades, as well as those who still dream of gallant Christian warriors putting a stop to the enemies of Christendom.

Jacques de Molay (c. 1240–1250 – 1314) was the 23rd and last grand master of the Knights Templar, leading the order sometime before April 20, 1292 until it was dissolved by order of Pope Clement V in 1312

Image Credits: 1 Jerusalem Panoramic (wikipedia.org) 2 Temple given to Templars (wikipedia.org) 3 Temple Mount (wikipedia.org) 4 Seal of Templars (wikipedia.org) 5 Bernard Preaching (wikipedia.org) 6 Saladin and the Knights (wikipedia.org) 7 Hugues de Payens (wikipedia.org) 8 Krak des Chevaliers (wikipedia.org) 9 Philip IV of France (wikipedia.org) 10 Clement V (wikipedia.org) 11 Jacques de Molay (wikipedia.org)