The Birth of Rudyard Kipling, 1865

“But test everything; hold fast what is good.” —I Thessalonians 5:21

The Birth of Rudyard Kipling,

December 30, 1865

udyard Kipling published eleven novels and hundreds of poems, short stories, and newspaper articles between 1881 until his death in 1936. From 1890 on, he was one of the most famous story-tellers in the world, a uniquely gifted writer who drew on his experiences in India, the tales told him by his nurse, and his innate sense of the effects of Imperial Britain on the world. In 1889 he traveled throughout the United States for seven months, lionized wherever he stopped, including a day spent with Mark Twain in Elmira, New York. At the age of 26, Kipling married 29-year-old Caroline, “Carrie” Starr Balestier an American who kept their household accounts and correspondence, and bore him three children; she outlived him by three years.

udyard Kipling published eleven novels and hundreds of poems, short stories, and newspaper articles between 1881 until his death in 1936. From 1890 on, he was one of the most famous story-tellers in the world, a uniquely gifted writer who drew on his experiences in India, the tales told him by his nurse, and his innate sense of the effects of Imperial Britain on the world. In 1889 he traveled throughout the United States for seven months, lionized wherever he stopped, including a day spent with Mark Twain in Elmira, New York. At the age of 26, Kipling married 29-year-old Caroline, “Carrie” Starr Balestier an American who kept their household accounts and correspondence, and bore him three children; she outlived him by three years.

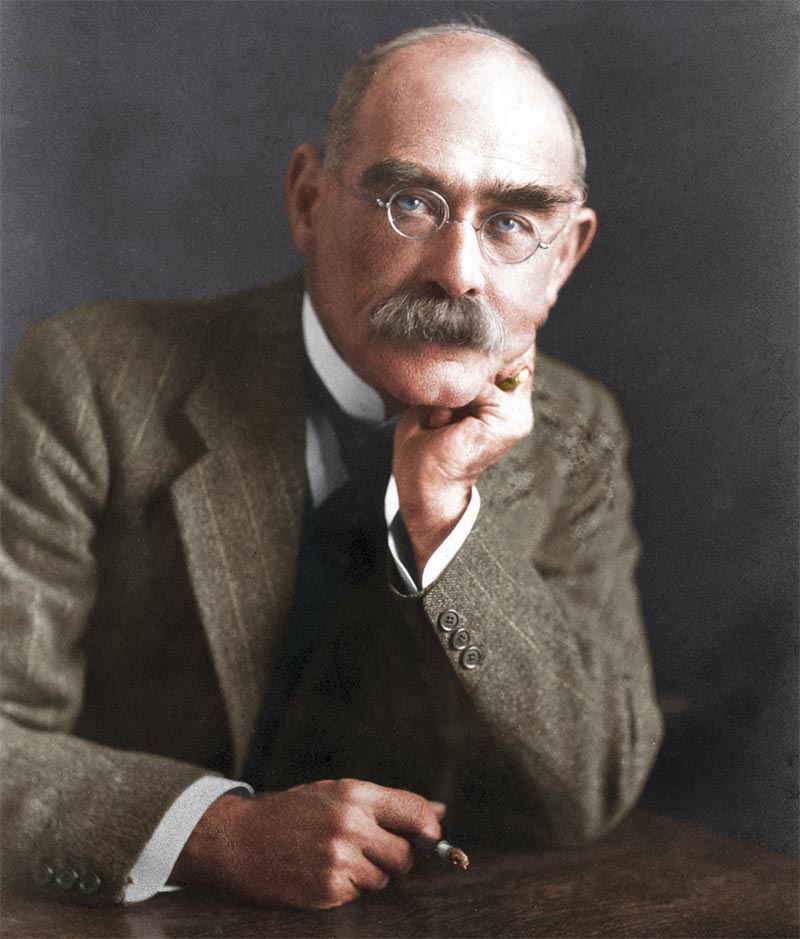

Born in British India, Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) was a celebrated English novelist, poet, short-story writer, and journalist

Kipling was born in Bombay, India to John Lockwood Kipling, a professor of architecture and the principal of the J.J. Art Institute in that city, and Alice MacDonald, daughter of a Methodist minister, and described as having a “lively tongue and a match for any wit.” As an “Anglo-Indian” Rudyard’s first five years were spent speaking the local language, and he used Indian idioms from his early learning in books and articles. Rudyard spent his first years in Bombay under the guardianship of Indian nurses and servants, one of whom sacrificed a goat to the god Kali during one of Rudyard’s early childhood illnesses.

Malabar Hill, Bombay, where Kipling was born

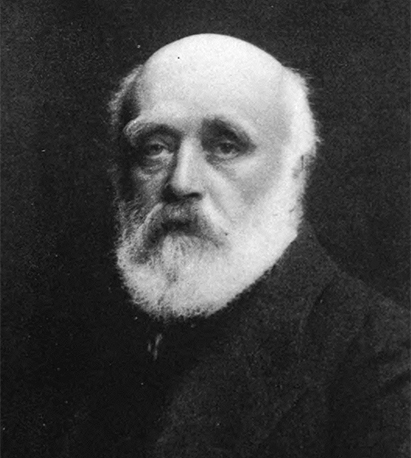

John Lockwood Kipling (1837-1911) father of Rudyard Kipling

Alice Kipling née MacDonald (1837-1910) mother of Rudyard Kipling

Just before his sixth birthday, Kipling and his little sister were left in England in the care of a retired officer and his wife, Rudyard’s parents slipping quietly away, never telling the children about their new circumstances. He lived under the tyranny of “Aunt Rosa” until his mother arrived one day from India to spend a summer with him in the country. One biographer suggests that Rudyard Kipling, in those seven years without family, was made to drink deeply of the “waters of Hate, Suspicion, and Despair,” an experience that instilled in him a stoicism that any suffering can be endured. It was also discovered that he had a serious eye problem that the wearing of glasses the rest of his life ameliorated.

Bombay (Mumbai) is situated on the west coast of India and as of 2018 was ranked 2nd most populous city in India and 7th most populous in the world

United Services College in Devon, established in 1874 by a company of army officers

His teen years were spent at the “United Services College” in North Devon, where its cheapness was exceeded only by its inferiority of education, and where he had to learn the skills of self-preservation (again), amid a tumult of teasing, bullying, and beating. The lives of potential civil servants and soldiers in the late 19th Century would hold the British Empire together. The ethos of the “public school” would appear in his novels like Stalky & Co (1899). Kipling returned to India in 1882 and worked as a journalist for seven years where he could hob-nob with his fellow upper middle-class Englishmen, as well as observe Indian life as it was lived in the street and on the farm. He filled his journals with light verse and poetry as well as sketches of Indian life. His Departmental Ditties, Plain Tales from the Hills, Soldiers Three, etc. brought accolades and awards from England and made him one of the greatest short-story tellers of all time. Three years after his death, Hollywood began making films based on his stories, from Gunga Din to The Jungle Book, from The Man Who Would Be King to Captains Courageous.

Rudyard Kipling (center) and other students of United Services College, c. 1882

Westward Ho!, England, location of the United Services College

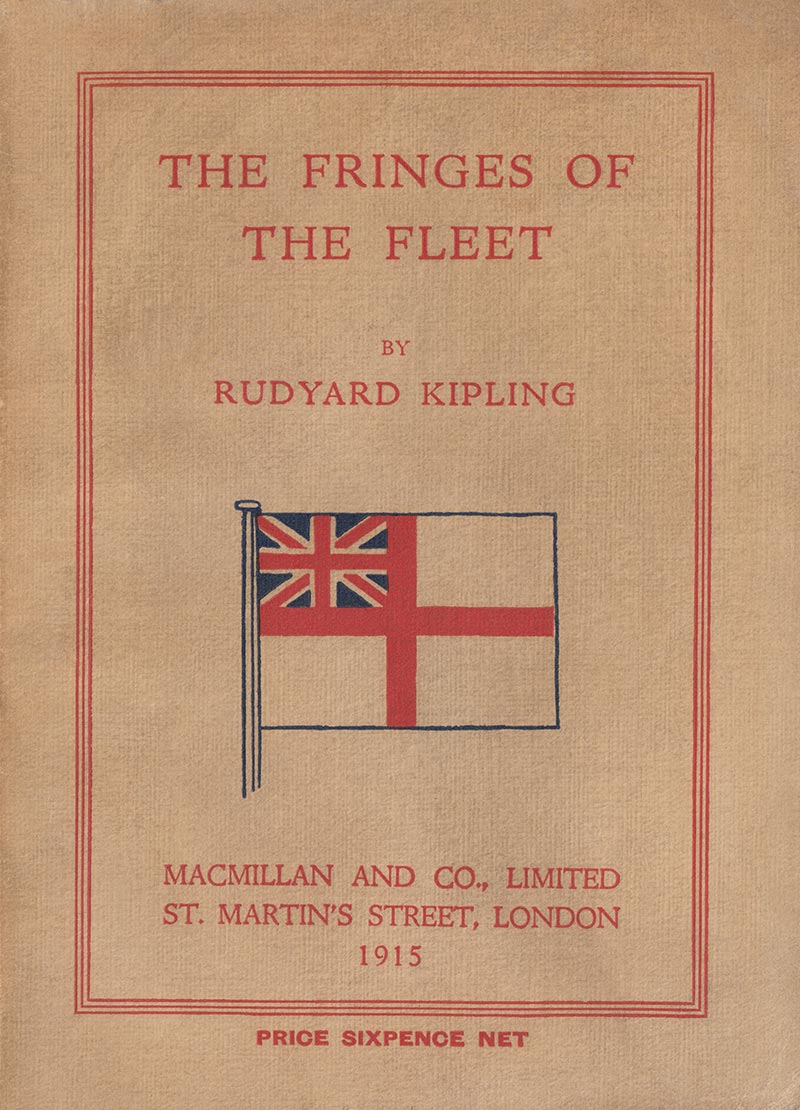

After a five-year sojourn in America, where he married and initially settled in Vermont and Connecticut, the Kiplings returned to England and settled in Sussex for the rest of their lives. He was the first Englishman to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize for literature (1907). His use of the colloquialisms of India and of British soldiers and sailors “broke new ground” and added color to his stories that no one else had ever done with success. Kipling was a master of glorifying and supporting the British Empire, and his books, along with those of his contemporary, and second most popular writer of books for young men, G.A. Henty, probably unknowingly recruited more civil servants and soldiers during that period than any other source.

A 1915 booklet by Kipling containing nautically themed essays and poems

Kipling’s home in Sussex, England from 1902 until his death in 1936

His son Jack was killed in action in the First World War, and Rudyard’s heart-breaking search for his son’s remains has inspired a book entitled My Son Jack. After that war, the literati and other liberal opponents of the British Empire classified Kipling as a “jingoistic imperialist.” Nonetheless, political incorrectness aside, most of his beloved books for children have never been out of print, such as The Jungle Book, and Puck of Pook’s Hill.

John “Jack” Kipling (1897-1915)

Rudyard Kipling died in 1936, age 70. One of his pall-bearers was his cousin Stanley Baldwin, the Prime Minister of England. He was buried at Westminster Abbey between Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy, and his casket was appropriately adorned with the British flag. As might be expected, Kipling’s works and conservative political views remain controversial in both India and Britain. Both of his homes in those two nations, however, are beautiful museums devoted to his memory and extraordinary literary talents, that still entertain us and elicit appreciation from readers today.

Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey, where Kipling’s remains were interred

Image Credits: 1 Rudyard Kipling (Wikipedia.org) 2 John Lockwood Kipling (Wikipedia.org) 3 Alice Kipling (Wikipedia.org) 4 Malabar Point (Wikipedia.org) 5 United Services College (Westwardhohistory.co.uk) 6 United Services College Students (Westwardhohistory.co.uk) 7 Westward Ho!, England (TripAdvisor.com) 8 The Fringes of the Fleet (Wikipedia.org) 9 Rudyard Kipling Home (Wikipedia.org) 10 John “Jack” Kipling (Wikipedia.org) 11 Poets’ Corner, Westminster (Wikipedia.org)

hen the Second World War began, the United States military high command realized that bombing the enemy’s war-production, submarines, and field forces would require new technology, new and more deadly machines, and strategies that would complement or even replace ground forces. The airplanes of the First World War proved inadequate for most tactical missions in the Second. American manufacturers competed to design new fighters and bombers, and then convince the Army to buy their models. Automobile plants were converted to the production of both ground armored vehicles and flying machines. New manufacturing plants sprouted in many cities of the United States. Consolidated Aircraft began building planes in the 1920s. By 1936 they had landed a contract to build the PBY Catalina for the United States Navy, a sea-landing aircraft that they continued to build throughout WWII, used primarily in the Pacific Theatre of Operations.

hen the Second World War began, the United States military high command realized that bombing the enemy’s war-production, submarines, and field forces would require new technology, new and more deadly machines, and strategies that would complement or even replace ground forces. The airplanes of the First World War proved inadequate for most tactical missions in the Second. American manufacturers competed to design new fighters and bombers, and then convince the Army to buy their models. Automobile plants were converted to the production of both ground armored vehicles and flying machines. New manufacturing plants sprouted in many cities of the United States. Consolidated Aircraft began building planes in the 1920s. By 1936 they had landed a contract to build the PBY Catalina for the United States Navy, a sea-landing aircraft that they continued to build throughout WWII, used primarily in the Pacific Theatre of Operations.