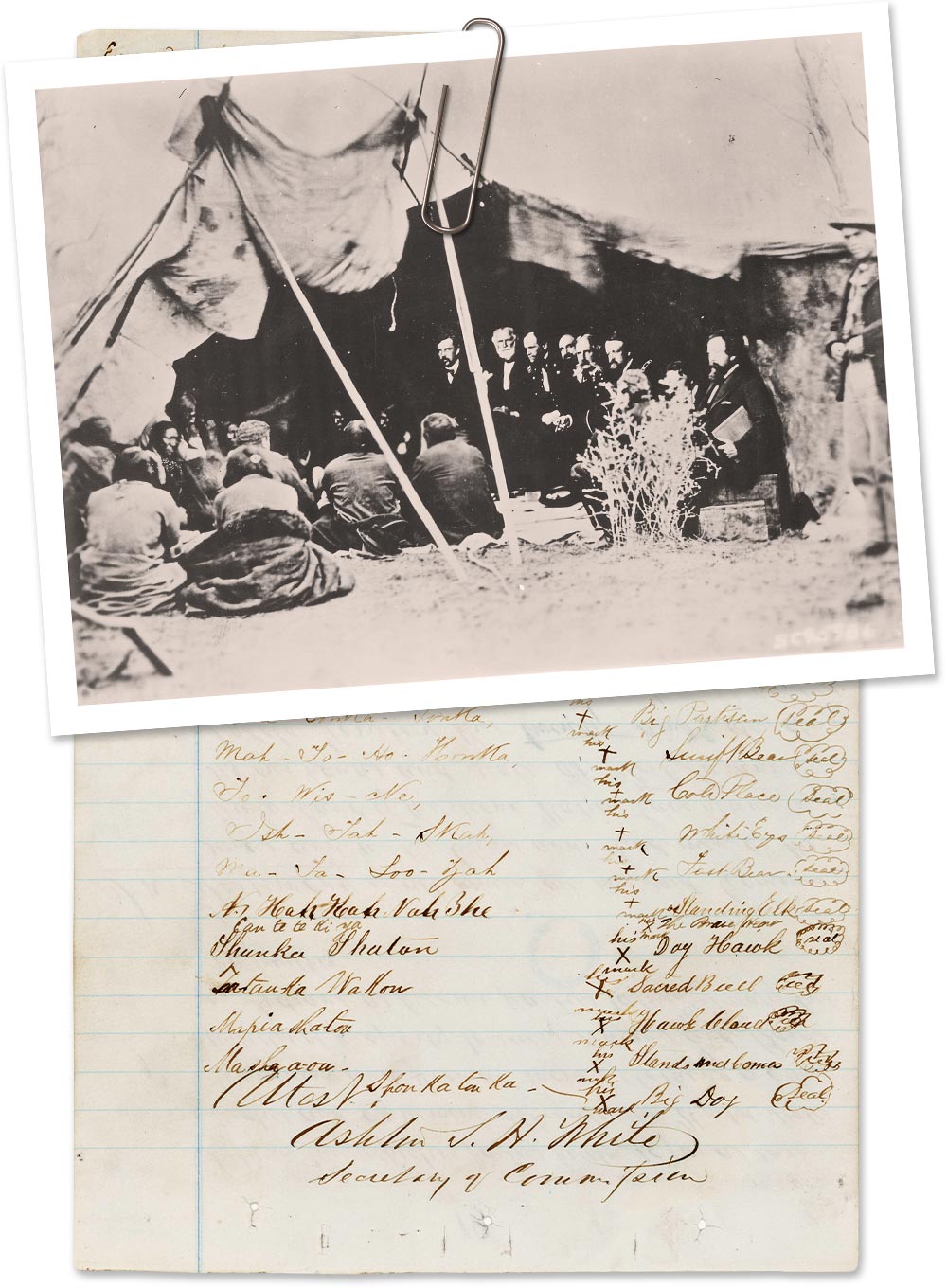

![]() n 1868 at Fort Laramie, in Goshen County, Wyoming, the United States Government signed a treaty with the Sioux Nation, wherein the Sioux agreed to accept all the land west of the Missouri River in South Dakota as reserved for them, including the Black Hills, and the United States agreed to stay out of land reserved for the tribes. In 1874, George Armstrong Custer led a military expedition into the Black Hills, an area sacred to the Lakota, and reserved exclusively for their use. Custer’s entourage discovered gold there, and white miners from all over the United States flocked to the Black Hills to get in on the bonanza. Needless to say, war erupted again between the Sioux and the interlopers stealing their land and gold. The government in Washington decided it would be easier to create different reservations for the native tribes than try to drive out the American miners. A Hunkpapa Sioux leader named Sitting Bull, who had spent much of his life fighting other tribes and the white soldiers and settlers, was called upon once again to employ his considerable skills in a last gasp to preserve the territory and honor of the tribes.

n 1868 at Fort Laramie, in Goshen County, Wyoming, the United States Government signed a treaty with the Sioux Nation, wherein the Sioux agreed to accept all the land west of the Missouri River in South Dakota as reserved for them, including the Black Hills, and the United States agreed to stay out of land reserved for the tribes. In 1874, George Armstrong Custer led a military expedition into the Black Hills, an area sacred to the Lakota, and reserved exclusively for their use. Custer’s entourage discovered gold there, and white miners from all over the United States flocked to the Black Hills to get in on the bonanza. Needless to say, war erupted again between the Sioux and the interlopers stealing their land and gold. The government in Washington decided it would be easier to create different reservations for the native tribes than try to drive out the American miners. A Hunkpapa Sioux leader named Sitting Bull, who had spent much of his life fighting other tribes and the white soldiers and settlers, was called upon once again to employ his considerable skills in a last gasp to preserve the territory and honor of the tribes.

The signing of the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, and one of the signature pages from the treaty including marks from the tribal leaders

Sitting Bull (c. 1830-1890) in 1883

Sitting Bull was likely born around 1830 in a settlement of Hunkpapa Sioux, and named “Jumping Badger.” At the age of 14, he participated in a raid on a rival tribe (Crow), and “counted coup,” for which he received as reward from his father, a warrior’s horse, an eagle feather, a shield, a feast, and the name that he carried the rest of his life. Twenty years later, more than two thousand Union soldiers attacked a Lokata village in the “Dakota Indian War,” a village defended by warriors led by Sitting Bull and Gall. Later the same year, Sitting Bull led an attack in which he was struck by a soldier’s bullet which went through his hip and out his back, without serious harm.

Killdeer Mountain Battlefield where fighting ensued after some 2,200 Union troops attacked a Lakota village July 28–29, 1864

At 7,244ft, Black Elk Peak is the highest point in the Black Hills, a small and isolated mountain range that rises from the plains in western South Dakota, and extends into Wyoming

| Join Landmark Events for a 5-day tour of America’s Heartland. Venture by coach to the iconic attractions of the area: Black Elk Peak, Mount Rushmore, Badlands National Park, Devils Tower, & much more! Learn More > |

After the Civil War, the Great Northern Pacific Railroad attempted to survey and lay tracks across Lakota lands, but faced attacks by bands of Sioux warriors led by Sitting Bull, temporarily shutting down the railroad, which led to bankruptcy for men like Jay Cooke, the financier of the Union’s war against the South. After the discovery of gold in the Black Hills, mentioned above, The Great Sioux War erupted in the Dakotas, Wyoming, and Montana. The federal government in Washington ordered the Sioux tribes on to reservations outside the Black Hills, and the shooting began. President Grant ordered the army to track down any natives found outside the reservation and force the “hostiles” by any means necessary back to the reservations. Many natives complied and returned in peace.

Jay Cooke (1821-1905) financier of the Civil War as well as the postwar development of railroads in the North

Sitting Bull’s reputation and natural leadership skills led to great respect both from his and other tribes. His name appeared in Eastern newspapers, and his exploits were recorded for all to read. A ceremonial alliance brought the Northern Cheyanne (traditional enemy of the Sioux) into conjunction with Sitting Bull’s bands. Numerous hostiles were attracted to Sitting Bull’s camp until a camp of more than 10,000 people were assembled. Lt. Col. Custer, the leader of the 1874 expedition, Civil War veteran, and Indian chaser, discovered the three-mile-long camp and attacked with but three battalions of the 7th Cavalry Regiment. Sitting Bull remained primarily the spiritual leader of the assembled tribes as the young men swarmed to the attack along the Little Big Horn River/ “greasy-grass” region in Montana.

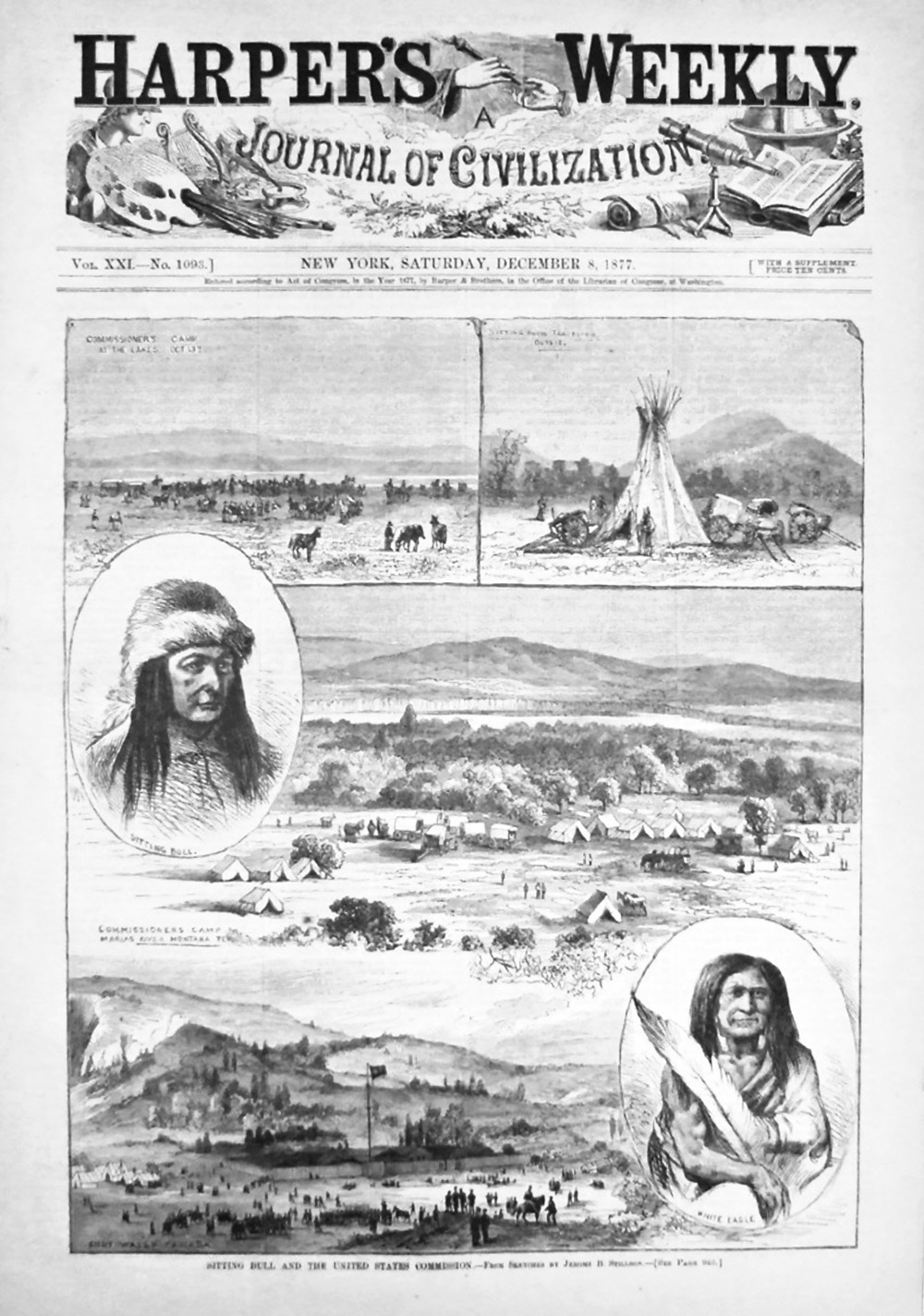

Sketches of Sitting Bull are featured on the cover of a December 1877 issue of Harper’s Weekly

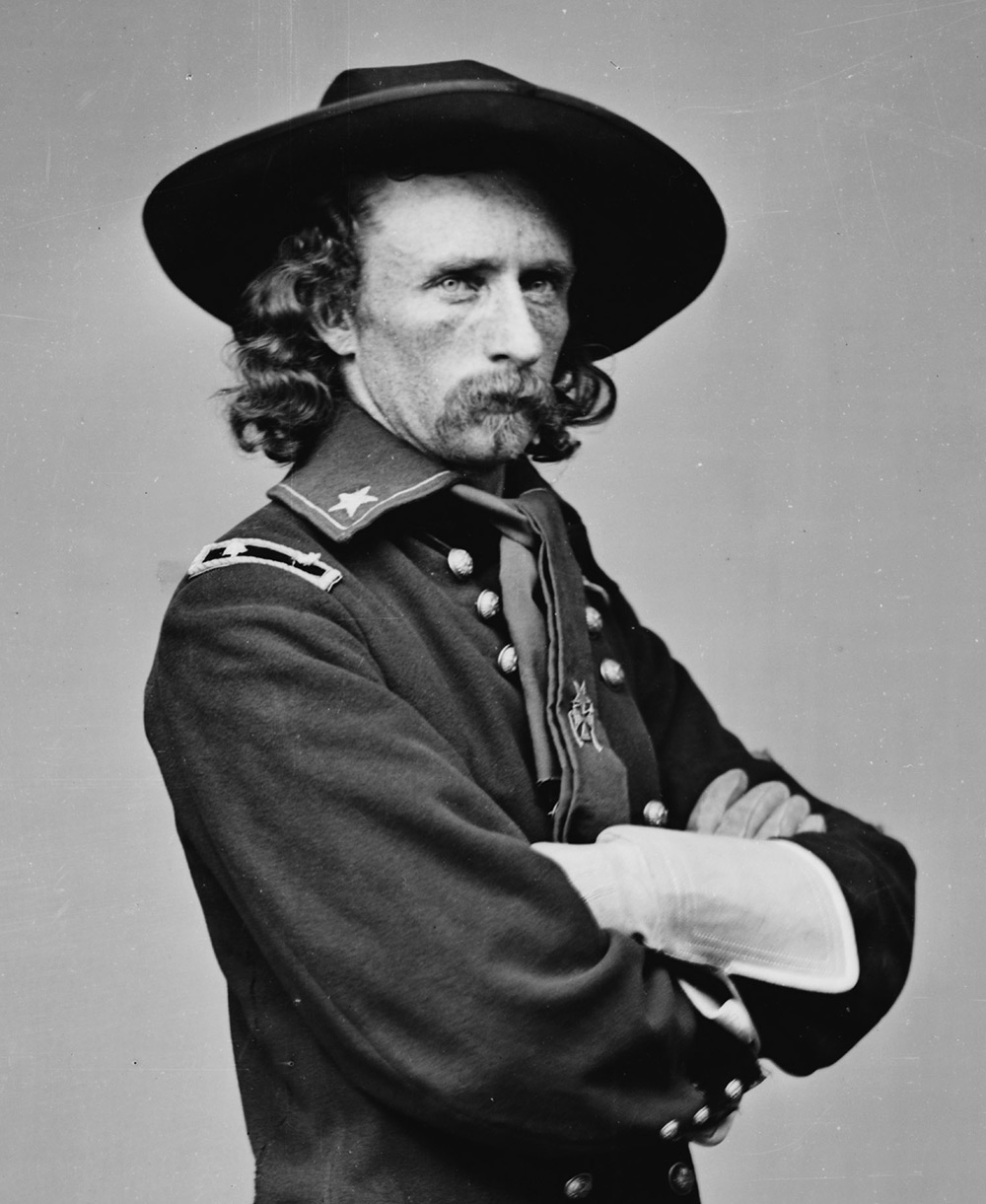

George Armstrong Custer (1839-1876) officer and cavalry commander during the Civil War and the American Indian Wars

With the total destruction of one battalion—including the death and mutilation of Custer—and heavy losses in the other two, the headlines in the eastern newspapers screamed massacre, shock and outrage. Thousands of soldiers, cavalry, infantry, and artillery were sent to the Dakotas to track down the fleeing tribes and kill or capture them all. Sitting Bull escaped to Canada, where he remained in exile for four years. After making peace with several traditional enemy tribes in Canada, as well as the Canadian government, Sitting Bull returned to the United States in 1881 with 186 starving family and followers, and surrendered to the Army.

The Battle of Little Bighorn, June 25-26, 1876

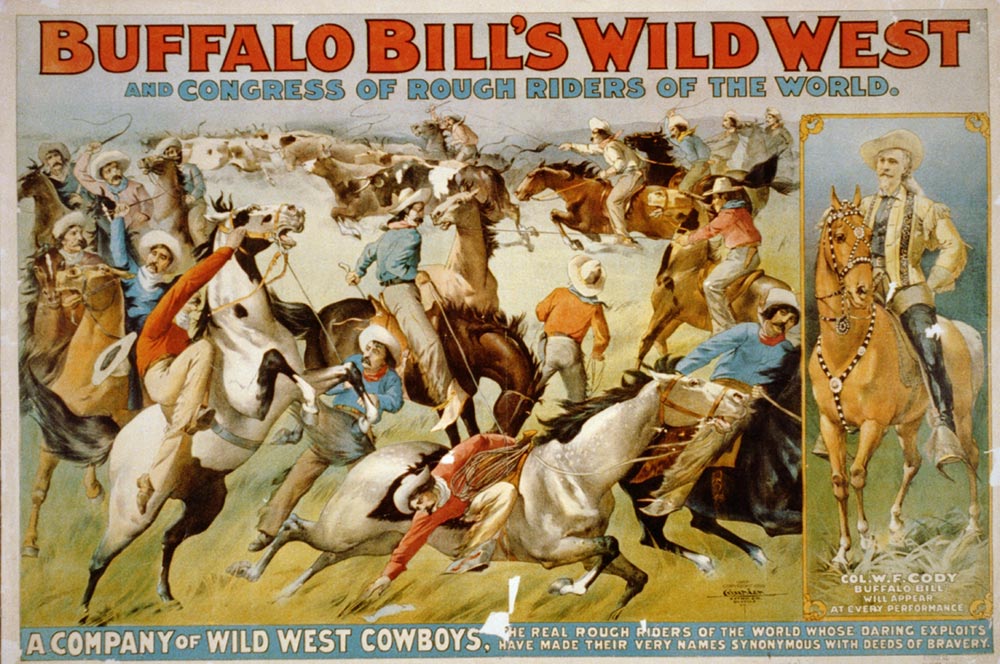

In 1885, Sitting Bull was allowed to join Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, where he rode once around the arena each night for fifty dollars per week. He met President Grant and other dignitaries, who appreciated the old Hunkpapa Sioux leader’s newfound respect for his former enemies and willingness to subordinate himself. He gave speeches in the Sioux language, which translators said were supportive but which some historians believe were full of curses and accusations against his captors. He did make a small fortune signing autographs and getting his picture taken.

Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill Cody

A circus poster c. 1899 advertising Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show

In the late 1880s and early 90s, a native “spiritual” movement centered on the “Ghost Dance” attracted many followers from different tribes, including many Sioux. In fear that Sitting Bull might join the movement and lead a rebellion, the Army ordered that he be arrested and incarcerated. They surrounded his house on December 15, 1890 and ordered him out under arrest. In the ensuing confusion and resistance, followers rushed to the house. Gunfire ensued with the shooting of the arresting officer by a Sioux warrior. Sitting Bull was then killed on the spot. When the smoke cleared, six police were dead along with seven of Sitting Bull’s followers.

A Sioux Ghost Dance

Two of Sitting Bull’s wives and two of his daughters pose outside the door of the cabin where he was slain several weeks prior

The old warrior has been the subject of admiration and respect ever since that time, and has been portrayed in movies and books multiple times. His living grandsons, some of whom are professing Christians, keep alive his memory, as do the Lakota as a tribe. His grave, well-marked, is in Mobridge, South Dakota.

Image Credits: 1 Sitting Bull (Wikipedia.org) 2 Signing of the Treaty of Fort Laramie (Wikipedia.org) 3 Treaty Signatures (Wikipedia.org) 4 Killdeer Mountain (Wikipedia.org) 5 Jay Cooke (Wikipedia.org) 6 Black Elk Peak (Wikipedia.org) 7 Harper’s Weekly (Wikipedia.org) 8 George Armstrong Custer (Wikipedia.org) 9 The Battle of Little Bighorn (Wikipedia.org) 10 Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill (Wikipedia.org) 11 Wild West Poster (Wikipedia.org) 12 Ghost Dance (Wikipedia.org) 13 Sitting Bull Family (Wikipedia.org)