The Death of J. Gresham Machen, 1937

“These were more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they received the word with all readiness of mind, and searched the scriptures daily, whether those things were so.” —Acts 17:11

The Death of J. Gresham Machen,

January 1, 1937

![]() he First World War shattered, for many intellectuals, what remained of the philosophical and theological presuppositions that had undergirded Western Civilization for centuries. While those ideas had been under attack for generations, the utter devastation and slaughter of the War had profound implications for the cultural world that emerged in the 1920s. Liberal theologians, especially in Germany, seemed to have a free field of fire against the orthodox Christian views of the Bible’s authorship, inerrancy, historicity, and accuracy—an influence known appropriately as “Modernism.” Those challenges raged in the late 19th Century and early 20th, and now seemed poised to completely overwhelm the Church. A modest and brilliant champion from Princeton stepped into the lists to defend the Faith in America, John Gresham Machen. He became liberal Protestantism’s greatest nightmare.

he First World War shattered, for many intellectuals, what remained of the philosophical and theological presuppositions that had undergirded Western Civilization for centuries. While those ideas had been under attack for generations, the utter devastation and slaughter of the War had profound implications for the cultural world that emerged in the 1920s. Liberal theologians, especially in Germany, seemed to have a free field of fire against the orthodox Christian views of the Bible’s authorship, inerrancy, historicity, and accuracy—an influence known appropriately as “Modernism.” Those challenges raged in the late 19th Century and early 20th, and now seemed poised to completely overwhelm the Church. A modest and brilliant champion from Princeton stepped into the lists to defend the Faith in America, John Gresham Machen. He became liberal Protestantism’s greatest nightmare.

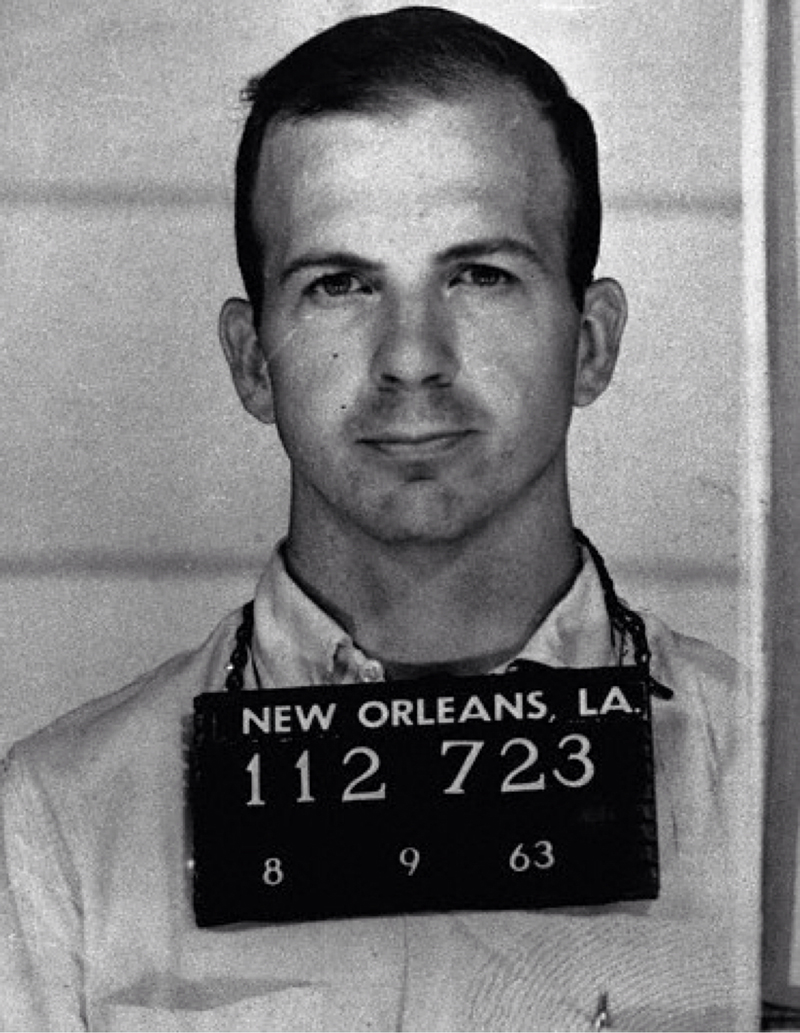

J. Gresham Machen, as he was best known, was born to a very devout Southern Presbyterian mother, and grew up in a genteel social milieu in Baltimore, in the last decade of the 19th Century. He graduated first in his class at Johns Hopkins in the classics in 1901, and from Princeton Seminary in 1905. Machen then sailed to Europe to immerse himself in the courses taught by the greatest modernist seminary professors and philosophers in Germany. By God’s grace, he saw through the friendliness and camaraderie of the great liberals, to challenge and refute their heresies and false assumptions.

J. Gresham Machen (1881-1937)

Upon his return to Princeton as Professor of New Testament in 1906, Machen developed a reputation for his challenges to both mainstream American pietistic Protestantism and the deadly cancer of European liberalism. His forthright apologetics came from a historic and Calvinistic foundation based on the virgin birth of Christ and the absolute historical integrity of the Bible. He took a year off to serve in the YMCA canteens in France during WWI. Upon his return, the intellectual challenges multiplied as did the controversies that followed his stands against the liberals.

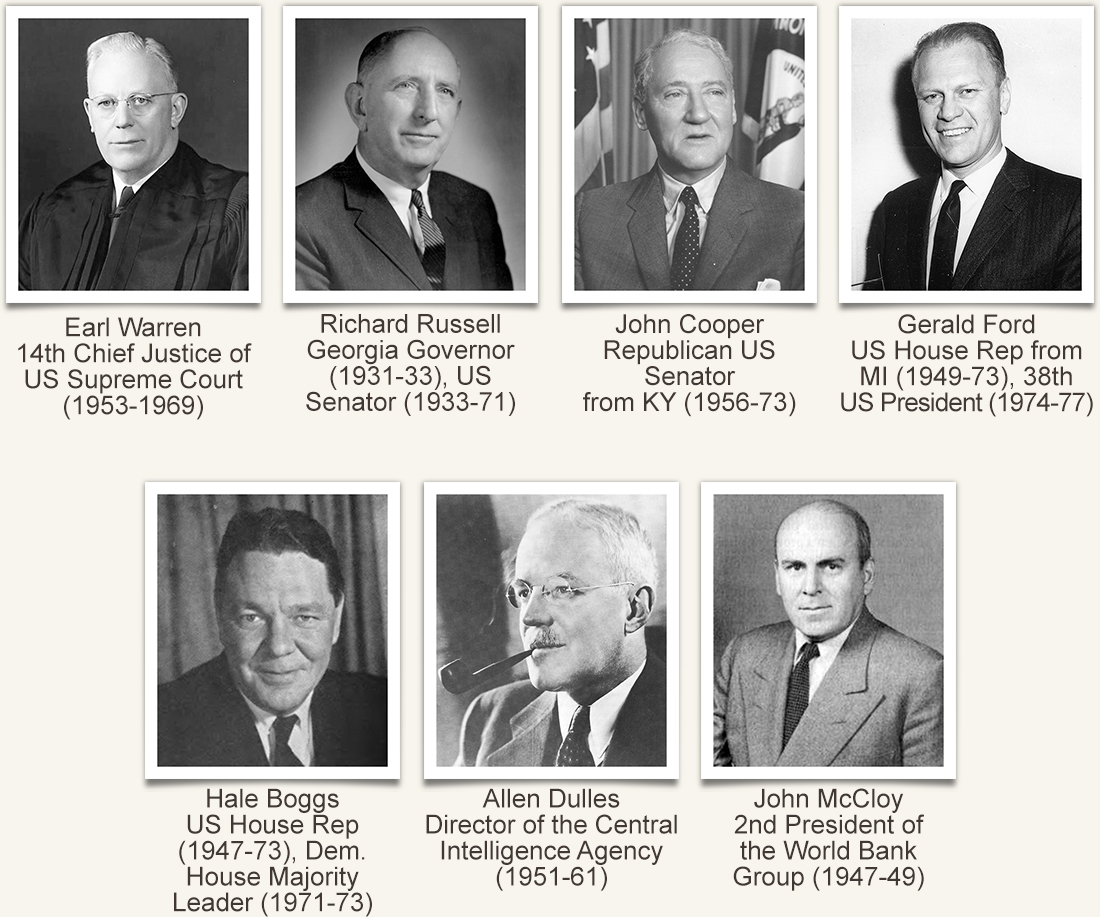

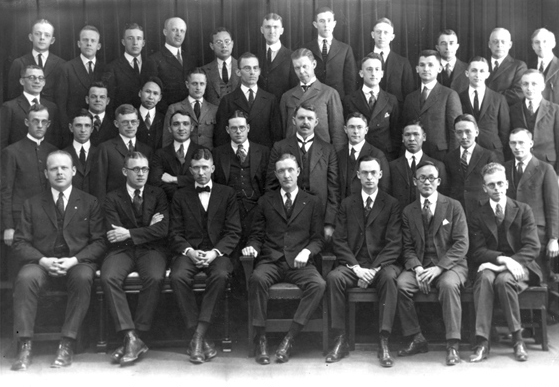

Princeton Theological Seminary Class of 1922, during Machen’s tenure as Professor of New Testament (1906-1929)

Princeton Theological Seminary in the 1800s

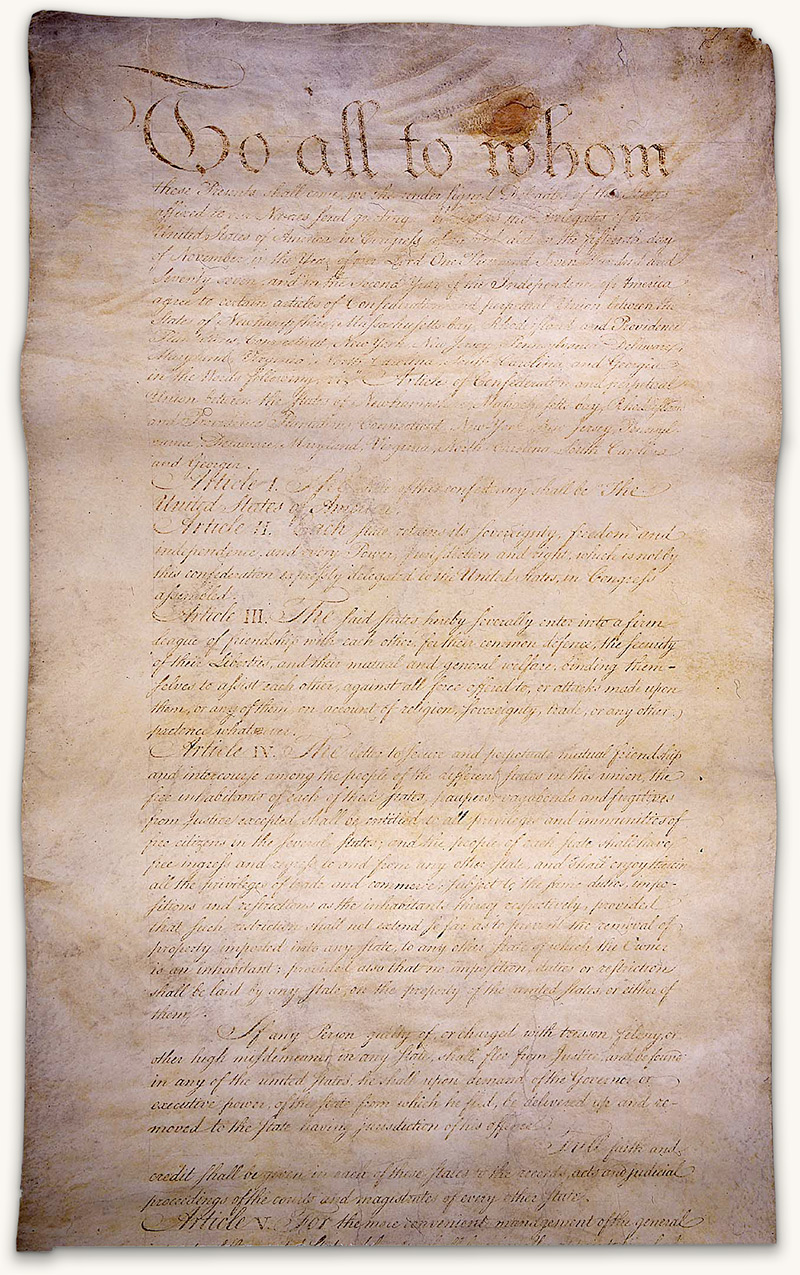

Liberal Protestantism “reduced Christianity to a set of general religious principles regarding the moral teachings of Jesus,” and they emphasized God’s love over all of His attributes, especially justice and man’s accountability for his sin. Machen asserted that liberalism was not just a form of Christianity, but an entirely different religion—not the Christianity of the Bible. His beliefs were rapidly declining in adherents at Princeton and in the Presbyterian Church USA to which he belonged, as more and more biblical doctrines were rejected and replaced by modern philosophical presuppositions. Liberalism penetrated the foreign mission board of the PCUSA, and in response, Machen helped create a conservative but “Independent Board of Foreign Missions,” based on fidelity to the inspired Word of God. In 1935, he was tried in the Church Courts and suspended from the ministry for fomenting “schism” in the Church.

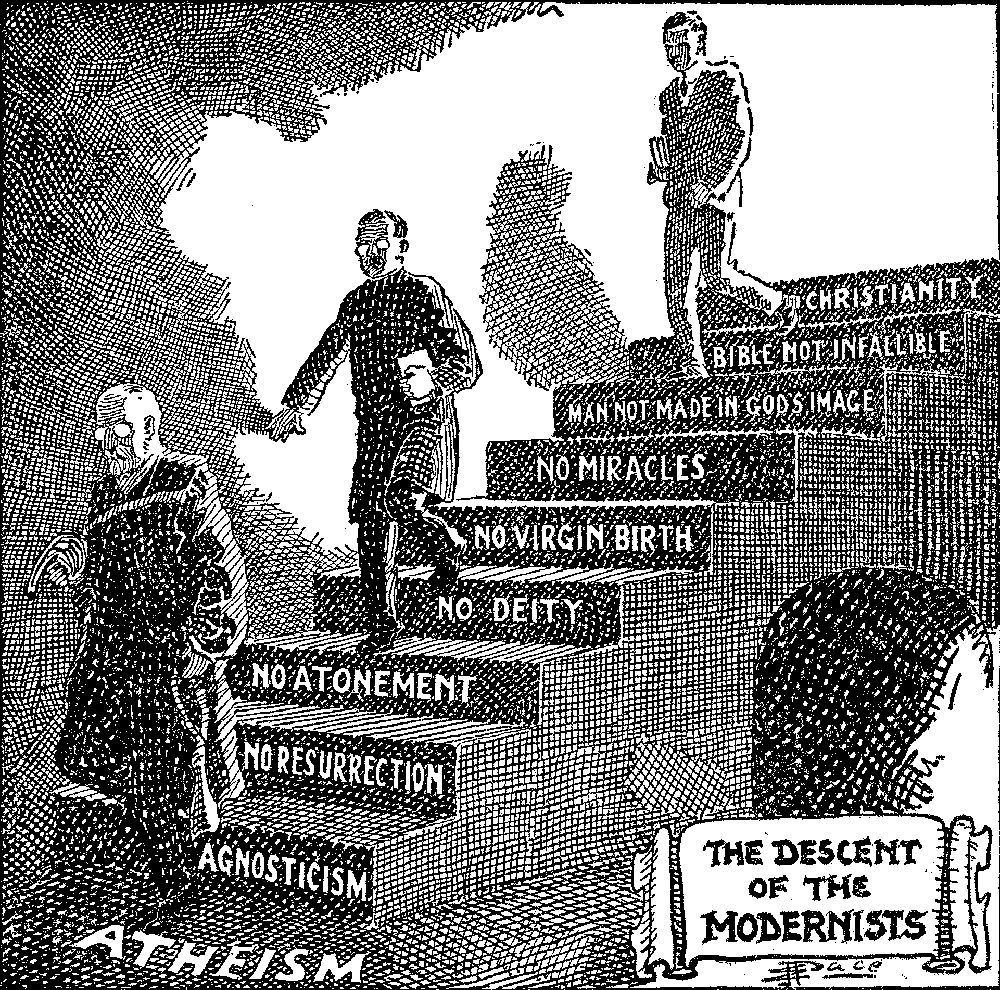

This Fundamentalist cartoon, first published in 1922, portrays Modernism as the descent from Christianity to atheism

Machen was instrumental in the formation of what became the Orthodox Presbyterian Church denomination and the creation of Westminster Seminary in Philadelphia, to train ministers loyal to the Word of God and uncompromising on the historic Christian doctrines. A number of Princeton theologians joined with him in the endeavor.

Machen Hall, Westminster Theological Seminary—notable alumni of the seminary include Francis Schaeffer, Greg Bahnsen and Alistair Begg, among others

In December of 1936, he came down with pneumonia while preaching in North Dakota and died on January 1, 1937, aged 55. Throughout the post-war era, Machen became the champion of the “fundamentalists” of America for his ability to meet the liberals on their own grounds and bring a scholarly and profound defense of Reformation Protestant theology. While men from other denominations embraced his defense of the faith, his own church proceeded to disavow him and the Word on which he stood. J. Gresham Machen did not fit into the radical fundamentalist rejection of alcohol, tobacco, and other extra-biblical cultural appurtenances, but he fought to the death over the historicity of the Bible, the Virgin Birth, and the Deity of Christ. His bestselling books took their place among Christian classics: The Origin of Paul’s Religion (1921), Christianity and Liberalism (1923), and The Virgin Birth of Christ (1930), among several others. With the death of Machen, the Church lost a great champion who was raised up by God in a volatile time for the Church in America.

Machen’s 1923 book Christianity and Liberalism was named one of the top 100 books of the twentieth century by Christianity Today one of the top 100 books of the millennium by World magazine

J. Gresham Machen: A Biographical Study, by Ned Stonehouse (Eerdmans, 1954)

Defending the Faith: J. Gresham Machen and the Crisis of Conservative Protestantism in Modern America, by D.G. Hart (P&R, 1994)

<smallImage Credits: 1 J. Gresham Machen (Wikipedia.org) 2 Princeton Class of 1922 (Wikipedia.org) 3 Princeton Theological Seminary (Wikipedia.org) 4 The Descent of the Modernists Cartoon (Wikipedia.org) 5 Machen Hall, Westminster Theological Seminary (Wikipedia.org) 6 Christianity and Liberalism (Amazon.com)