“Fear not the things which thou art about to suffer: behold, the devil is about to cast some of you into prison, that ye may be tried; and ye shall have tribulation ten days. Be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee the crown of life.” —Rev. 2:10

The Martyrdom of Hugh M’Kail, December 22, 1666

![]() he roll of Christian martyrs extends back in time to the days following the resurrection of Our Lord. It continues daily in many far-flung nations of the earth. Jesus Himself told the Apostles to expect to die for their faith, a prospect they embraced, not knowing the time, place, or character of their death. Some of the saddest and yet the most triumphant stories of the few martyrs we know by name, are the ones murdered in “Christian” countries by men claiming to be fellow-believers.

he roll of Christian martyrs extends back in time to the days following the resurrection of Our Lord. It continues daily in many far-flung nations of the earth. Jesus Himself told the Apostles to expect to die for their faith, a prospect they embraced, not knowing the time, place, or character of their death. Some of the saddest and yet the most triumphant stories of the few martyrs we know by name, are the ones murdered in “Christian” countries by men claiming to be fellow-believers.

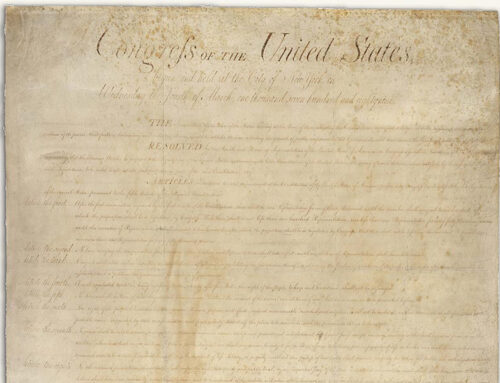

The Signing of the National Covenant in Greyfriars Churchyard, 1638

as portrayed by William Hole

Hugh M’Kail was born in 1640, and raised by his namesake uncle, in the midst of the “Second Reformation” in Scotland. The National Covenant had been recently circulated and signed by multiple thousands, the General Assembly had excommunicated the corrupt Anglican bishops in Scotland, the national legislature was filled with Church elders who were in almost total sympathy with the godly transformation of the Church and the culture, as the greatest spiritual revival since the days of John Knox swept through the nation. Hugh joined in the joyous triumph of spiritual renewal, even as the dark clouds of controversy and political disruption ensued in the 1650s.

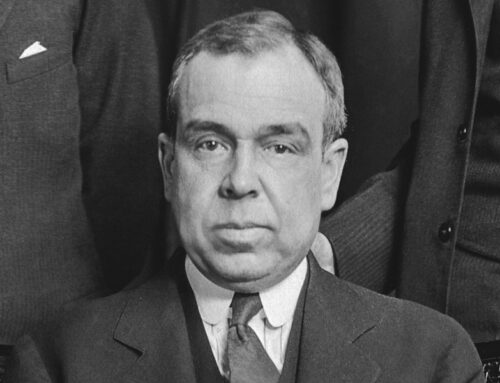

Charles II of England (1630-1685)

Having lived through the turmoil of Cromwellian occupation and division in the churches, Hugh attended the University of Edinburgh, where he received intense training for taking his place in Scotland among the ministers still loyal to the Covenants. He ardently defended the belief that the Lord Jesus Christ is the head of the Church, and the Bible determinative of how God should be worshipped. At the time of his graduation in 1660, such a belief was considered treason by the new King of England, Charles II, recently returned from European exile and determined to exert his headship and control over all the churches of the realm through the rule of his bishops, regardless of the resistance of Presbyterian Scotland. Twenty-year-old Hugh was licensed to preach by his presbytery in 1661, and began what would prove to be just one year of public preaching.

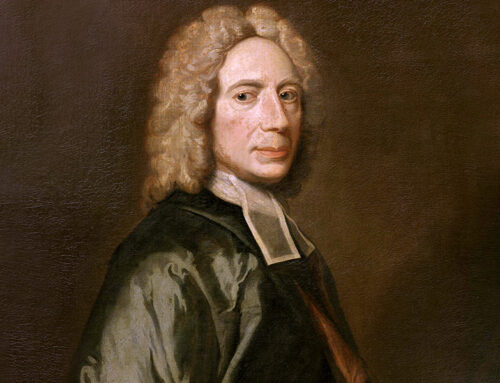

A Scottish conventicle (illegal church service)

Hugh M’Kail’s powerful and effective sermons came to an end in the High Church of Scotland, St. Giles, on the Sunday before more than 400 ministers were expelled from their pulpits in Scotland by order of the monarch. They had refused to renounce the National Covenant, at the heart of which was sworn affirmation of the “crown rights of Jesus Christ over the Church”. In his last sermon M’Kail said the Church and the people of God had been “persecuted by a Pharaoh upon the throne, a Haman in the State, and a Judas in the Church”. A party of horsemen were sent the next day to apprehend him, but Hugh escaped Edinburgh and hid out at his father’s house near Liberton, today a suburb of Edinburgh. For the next four years he managed to avoid arrest, for dissenting preachers continued to minister in conventicles (illegal worship services) and were attacked and punished by teams of commandos sent out by the government for that purpose.

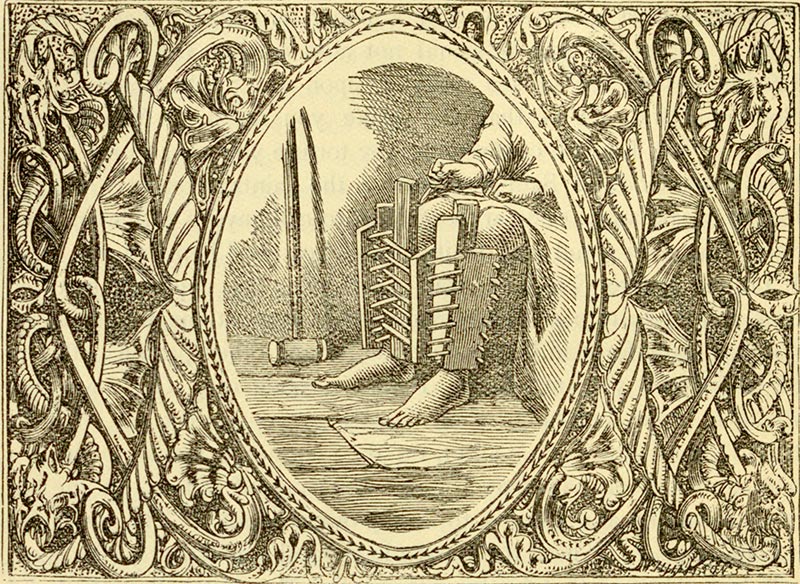

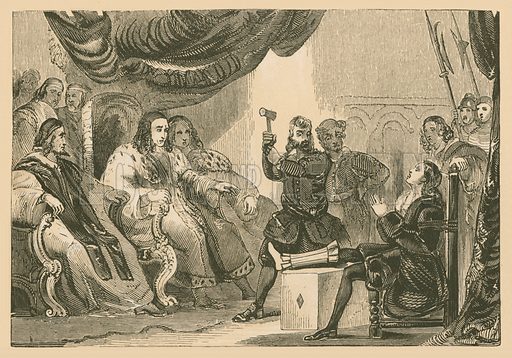

“The Boot”, a device of torture, used to slowly crush the leg

In 1666, after a brutal attack on an elderly man in Dumfries, some young Covenanters rescued him and in the ensuing fracas, killed a soldier. Realizing fierce retribution would be coming, the men took up arms and called for others to join them. In the course of a long march to Edinburgh to seek a redress of grievances, the 900 Covenanters, mostly farmers, few with firearms, were met by an army of 3,000 soldiers who were called out to stop them, and a battle ensued at Rullion Green in the Pentland Hills. Hugh M’Kail joined the march briefly, although he was suffering from a wasting disease, exhausted and broken down. The day before the engagement, Hugh dropped out and left to return home.

Seized along the way, carrying a sword and mounted, the pastor was taken to Edinburgh and thrown in the tollbooth prison. The “Secret Council” interrogated him, demanding an account of his participation and the names of everyone that he knew who had joined in the armed protest. Refusing to or unable to comply, Hugh was encased in the most painful torture device of the times known as “The Boot”. That instrument destroyed his leg, with no result of information. He affirmed his loyalty to both King and Covenant, and declared his innocence of any rebellion. The Council convicted him of treason, nonetheless, for not agreeing to the Royal Supremacy over the Church and for joining a rebellion designed to overthrow his authority.

Hugh M’Kail tortured with the Boot

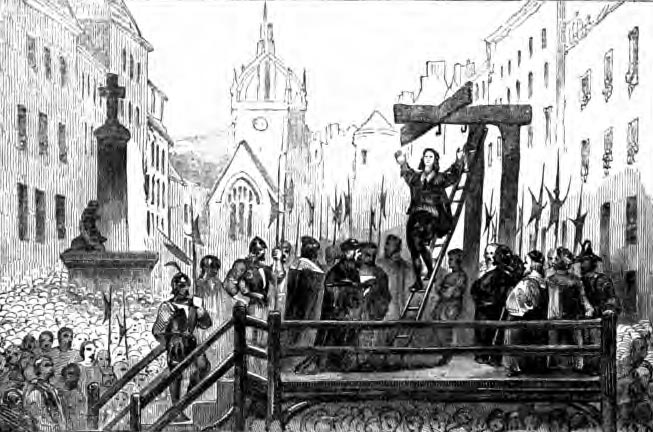

The original site of the “Mercat Cross”, High Street, Edinburgh, where many were martyred

On December 22, 1666 Hugh M’Kail went to the scaffold at the “Mercat Cross”, where other martyrs, like James Guthrie before him and Donald Cargill after, were executed. With praise on his lips to be counted worthy of dying for Christ, all of his last words were recorded by his father and cell-mates, as well as the multitude of weeping onlookers, for he was greatly beloved.

Scene of Hugh M’Kail’s execution, December 22, 1666, amid “such a lamentation”, says historian James Kirkton, “as was never known in Scotland before, not one dry cheek upon all the street, or in all the numberless windows in the market-place.”

It is not possible to know how much longer Hugh M’Kail would have lived, given his ill-health and his participation in the conventicles, had he not ridden out to satisfy his curiosity about the protesters marching on Edinburgh. Nonetheless, his forthright testimony, willingness to obey Christ regardless of the unbiblical dictates of the state to conform, and his confidence of his future in heaven, provide a sobering and faithful example for us today.

The Scots Worthies by John Howie