The Pazzi Conspiracy to Assassinate

the Medici Family, April 26, 1478

![]() n the late 1400s, the country we now call Italy was divided into many states and governed each by their own rulers. In the north, Milan’s form of government was a Duchy and thus they were ruled by a Duke. Seafaring Venice had a Doge, Naples a king and the people of Florence had a republic. Over them all, in matters religious and ever-increasingly secular, was the authority of the Pope in Rome, who, in the beneficence of his own office, had granted unto himself certain lands bordering Florence which he called Papal States.

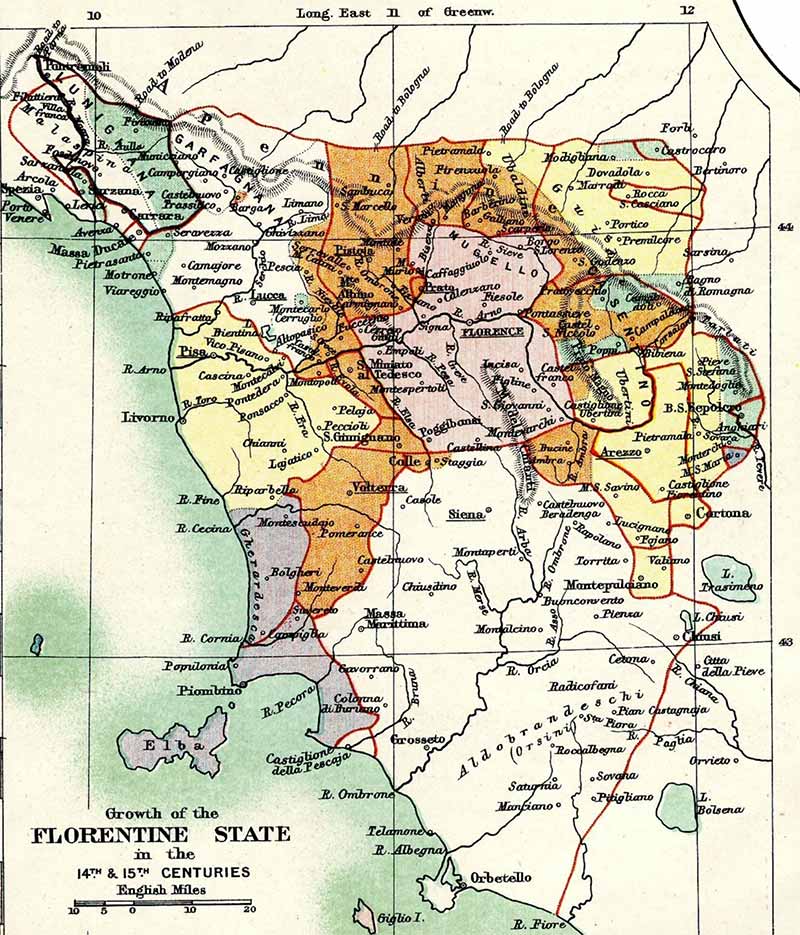

n the late 1400s, the country we now call Italy was divided into many states and governed each by their own rulers. In the north, Milan’s form of government was a Duchy and thus they were ruled by a Duke. Seafaring Venice had a Doge, Naples a king and the people of Florence had a republic. Over them all, in matters religious and ever-increasingly secular, was the authority of the Pope in Rome, who, in the beneficence of his own office, had granted unto himself certain lands bordering Florence which he called Papal States.

A map of the spread of the Florentine state in the 14th and 15th centuries

When the supreme head of the church and final authority figure for all earthly matters is your neighbor who cultivates his lands and trades his profits through your own, it is easily assumed there might be friction. And considering with whom you have your complaint, that it would remain unresolved. Such were the relations between the republic of Florence and the Papal States in the year 1478.

Pope Sixtus IV (born Francesco della Rovere; 1414-1484)

That is not to say some in Florence did not court papal favor—the Republic’s two leading families, the Medici and the Pazzi, had both vied to be the Pope’s bankers, with the Pazzi eventually securing that prize. Such success cost the Pazzi’s trust and status in their own country, the republic becoming more and more supportive of their rival, the Medici family.

With the ruling Medicis having recently thwarted an attempt by the Pope to seize more lands in the Romagna, a plot was hatched to remove their pesky influence by the Pazzi family—in league with a disgruntled Cardinal from Pisa and Pope Sixtus’ own nephew—leaving the “Holy Father” plausibly blameless for the ensuing coup.

Florence Duomo or Santa Maria del Fiore (Saint Mary of the Flower), site of the assassinations, as viewed from Michelangelo Hill, Florence, Italy

As is common amongst the agents of greed and envy, the conspirators had no qualms traveling to Florence, enjoying the hospitality of their plotted victims and, in the case of Francesco Pazzi, embracing Lorenzo de Medici before mass to ensure he had not worn armor into the holy place. Lorenzo had not, having in good faith brought his whole family to worship God with his erstwhile opponents in the magnificent cathedral his grandfather had built, right in the heart of Florence.

Lorenzo de’ Medici (1449-1492)

Giuliano de’ Medici (1453-1478)

What occurred that Easter Sunday would become one of the most infamous scenes of Renaissance history. In front of an attendance of 10,000 in the church, the two Medici brothers, Lorenzo and Giuliano, (ages 29 and 24) were set upon with drawn knives by members of the Pazzi family and their mercenaries.

The ensuing grapple was so intense that one conspirator reportedly stabbed himself in the leg during the frenzy. Giuliano de Medici was so throughly assaulted that he died almost instantly, his body poetically fallen in front of the altar. Though himself wounded in the neck and pursued through the church, Lorenzo de Medici escaped his assassins with brave assistance from his mother and young wife who took refuge in the sacristy—a small, adjacent room.

Commemorative medal by Bertoldo di Giovanni, 1478, showing the assassination attempt

The Pazzi’s grand intentions for a public assassination of their rivals to cement their supremacy backfired gravely. Even before news of Lorenzo’s survival spread, the townspeople had furiously pursued the conspirators and detained them. The plot had been twofold: murder the Medici heirs and seize control of the senate. Both attempts were witnessed by the people and thwarted before they could fully succeed. In the case of the conspiring cardinal from Pisa, he was killed in the street where the crowd found him. The rest were summarily hung as traitors to the republic, their bodies flung out the windows of the Town Hall and left dangling there as a grim deterrence to those who might have sympathized with the plot.

1479 drawing by Leonardo da Vinci of hanged Pazzi conspirator Bernardo Bandini dei Baroncelli

Palazzo Vecchio is the town hall of Florence, Italy, overlooking the Piazza della Signoria—it was from these windows that the conspirators were hung after the Pazzi Conspiracy

The Republic of Florence harbored little doubt regarding the origins of this conspiracy, knowing the Pazzi would not dare such a thing without papal backing, with the involvement of the Pope’s nephew a further confirmation. This began a two year war between Florence and Rome. Among its many outcomes would be the surprising emergence of a pre-Protestant attitude towards the corruption of earthly magistrates, in the church or otherwise. The Pope misstepped not only in consorting with murderers, but also in excommunicating the entire Republic of Florence for their subsequent and lawful execution of the assassins.

Discovery and mutilation of the body of Jacopo de’ Pazzi, one of the Pazzi conspirators

Lorenzo de Medici’s fearless lead in ignoring papal censure and instead consolidating power amongst the local diocese primed the people of Florence for the firebrand preaching of Reformed forerunner Savonarola. His doctrine was fanatical, later twisted as his own ambitions clouded his gospel, but the meat of his teachings led to an intense change in the mood of Florence. Where once art, commerce and ancient philosophies flourished, bonfires of such “vanities” were held in the town square and condemnation passed on the corruption of the church and government at large.

Monument to Girolamo Savonarola, predecessor to Reformation in Italy

By the time of Lorenzo’s own death in 1492, Savonarola’s radical influence had achieved what the Pope could not: the people of Florence overthrew the rule of the very Medicis who once stood between them and papal damnation.

Image Credits: 1 Florentine State (wikipedia.org) 2 Pope Sixtus IV (wikipedia.org) 3 Florence Duomo (wikipedia.org) 4 Lorenze de’ Medici (wikipedia.org) 5 Giuliano de’ Medici (wikipedia.org) 6 Commemorative Medallion (wikipedia.org) 7 Hanging Conspirator (wikipedia.org) 8 Palazzo Vecchio (wikipedia.org) 9 Body discovered (wikipedia.org) 10 Girolamo Savonarola (wikipedia.org)