The Allied Air Force Begins Mercy Runs

Over Holland, April 29, 1945

n April 29, 1945, the greatest mercy operation of the Second World War began, although initially it had all the marks of a suicide mission, the risks being enormous and likelihood of success scant.

n April 29, 1945, the greatest mercy operation of the Second World War began, although initially it had all the marks of a suicide mission, the risks being enormous and likelihood of success scant.

Hatched in London, the idea was to utilize the allied air forces to feed the starving people of Holland. It was the last year of the war, and for five years previously, the Dutch had endured Nazi occupation as well as every deprivation of supplies and food that Germany herself faced as defeat grew inevitable. Those German soldiers occupying the Netherlands had been ordered to defend it to the last, and their measures to do so included mass flooding of agricultural land.

Members of the Veghel Resistance with troops of the United States 101st Airborne Division in Veghel, Netherlands, September 1944

Beyond being allies with the occupied Dutch, the air forces in particular owed them a great debt. Well over fifty percent of allied air crews were shot down during the war, and in Europe, those who managed to escape immediate capture were assisted in returning to England by the indomitable Dutch resistance. Such aid was not without chilling consequences if caught, and many Dutch families paid the ultimate price for the freedom of one downed airman.

Ground crew loading food supplies into slings for hoisting into the bomb bay of an Avro Lancaster for Operation Manna, Cambridgeshire, England

This mercy operation was close to foolhardy in both scale and dependence on the good faith of German soldiers. But with an approximate three and a half million Dutch on the brink of starvation, the plan was authorized. General Eisenhower began tenuous negotiations with German authorities in Holland, assisted by Swiss go-betweens, and the key aspect of their final agreement was that certain corridors would be opened for allied airmen to fly in without being fired upon.

An American B-17 unloads a load of food above the completely destroyed Schiphol Airport in May 1945 as part of Operation Chowhound

For the fleet of bomber crews who had spent their wartime careers in the exact same flight paths, dropping bombs on factories, submarine pens and worker facilities in occupied Europe, these weak agreements amongst enemies were of little comfort.

The raw courage required of these pilots and crews was immense when their orders came. They had to cross once more into enemy airspace—a suspended flak-filled hell in the skies that they knew all too well—and fly at 400 feet over German anti-aircraft guns to gently deposit their parceled provisions from their modified Bombay doors.

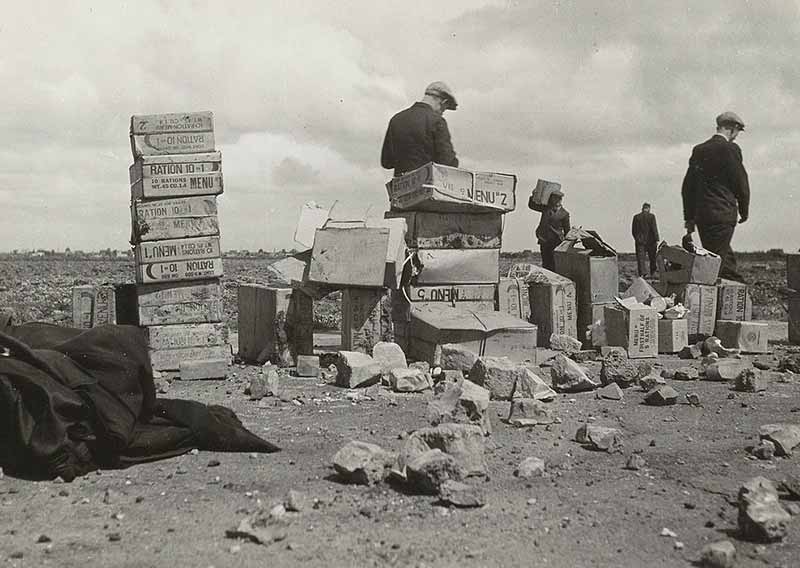

Food parcels being collected and sorted near Schiphol Airport, Amsterdam, Netherlands, May 1945 as part of Operation Chowhound

On April 29 the first mission was run; radio exchanges of good luck and prayers were sent between pilots as they crossed over. The eerie silence they were met with soon brought relief. The truce agreements were honored, and some allied airmen even observed the casual inaction of their enemies through their bombsights: smoking cigarettes and leaning against their once lethal anti-aircraft guns.

A Lancaster aircraft pulls up again after it has ejected its payload over Ypenburg, Holland

For ten consecutive days, British and American bomber groups ran over 5,500 sorties, dropping an estimated 10,000 tons of food on the starving and grateful Dutch. Their operations were named Manna and Chowhound, respectively.

A banner depicting the food drops over a store front in Amsterdam, Holland, June 1945

For most of the bomber crews, these became their last missions as providentially they coincided with the last days of the war in Europe: VE Day was declared on May 8, the same day that the last drop occurred.

Huge crowds gather in Whitehall to listen to Churchill’s Victory speech on “Victory in Europe Day”, May 8, 1945

Not many soldiers got so kind an epilogue to their war stories. Those who participated in these mercy missions spoke of it as being the most satisfying and healing thing they did in their entire lives. To fly over crowds of grateful citizens, dropping life rather than death for once, was a gentle last page of a very awful story for many of them whose role in the air had required much moral dilution in order to carry out their orders of terror and destruction.

Rotterdam, Holland in 1940 after bombing—an estimated 30,000 civilians were killed

According to many, there was no prettier sight in the world than the grateful messages the Dutch cut into their tulip fields: “thanks boys.”

“MANY…THANKS” spelled out in tulips for the pilots of operations Manna and Chowhound

Image Credits: 1 Dutch Resistance (wikipedia.org) 2 Loading up (wikipedia.org) 3 Aerial drops (wikipedia.org) 4 Sorting parcels (wikipedia.org) 5 Aerial drop (wikipedia.org) 6 Banner depicting drops (wikipedia.org) 7 London, May 8, 1945 (wikipedia.org) 8 Rotterdam (wikipedia.org) 9 “Many thanks” (wikipedia.org)