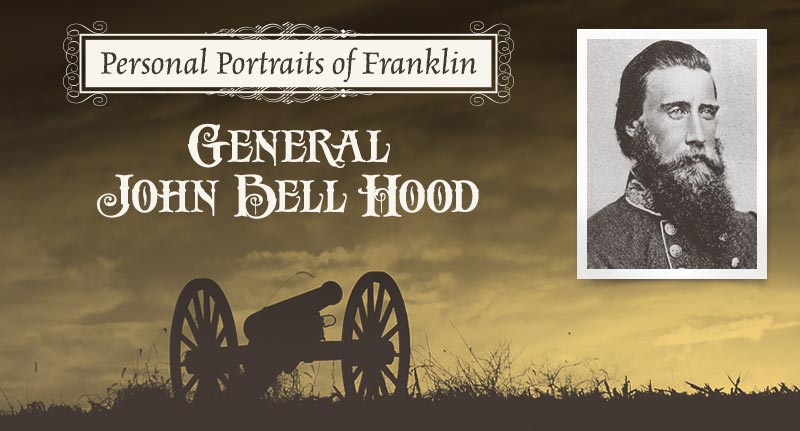

by Bill Potter

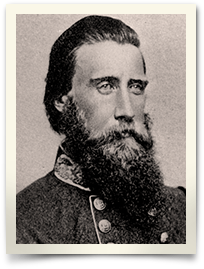

The commander of the Confederate army at the Battle of Franklin brought to that engagement more than three years of combat leadership, crippling wounds and serious interpersonal animosities toward subordinate generals. Neither his men nor most historians of the war have forgiven him for sending the Army of Tennessee to its destruction along the Harpeth River in 1864.

General Hood began the war as the regimental commander of the 4th Texas Infantry. His fighting qualities and example brought quick promotion to Brigadier General of the Texas Brigade. That unit fought so hard and with such success they forever adopted his name even after he left for higher command. General Lee called them his “Grenadier Guard.” At the battle of Gettysburg, Hood commanding a division as a Major General suffered a wound by an artillery shell burst early in the attack on Devil’s Den and Little Round Top. He lost the use of his arm and suffered constant pain, alleviated only by strong drugs.

When Longstreet’s Corps shifted to Georgia to fight in the Battle of Chickamauga, Hood was again struck down leading his men into battle. He lost one leg and ever after had to be strapped on his horse. As a fighting general Hood was at his best in divisional command but his aggressiveness and use of his troops as blunt force trauma against the Union lines usually resulted in success but inordinately heavy casualties. The Texan was not a man for maneuver.

In 1864 during the Atlanta Campaign, Hood was made commander of the army, probably a position too difficult for his abilities and temperament according to many historians. In modern times such a situation is known as the Peter Principle—“employees stop being promoted till they reach their level of incompetence.” Hood went instantly on the offensive to try and drive away the Federal troops besieging Atlanta. Union General William T. Sherman ultimately took Atlanta, inflicting twice as many casualties on the Confederates under Hood. The Confederate general had stood true to form with direct headlong assaults against entrenched enemies. No longer a brigade or division commander though—he hurled the whole army at the enemy.

In the cool and rainy Tennessee weather of November, 1864, John Bell Hood led his diminished army of Tennessee across the path of Union General John Schofield just north of Spring Hill to interpose between the retreating Yankees and their ultimate goal of safety in heavily fortified Nashville, a strategically sound plan. His Corps commanders let him down again through negligence, incompetence, or just confused Confederate leadership at one level or several, allowed the Federals to slip by in the night and fortify the already partially entrenched town of Franklin. Hood’s loose reins on his generals and the breakdown of good staff work brought his plans to naught.

General Hood, under the strain of campaigning, the probable effects of pain-killing meds, and sheer anger at his subordinates, called a council of war which turned out to be an order to charge across a mile of open ground against a well entrenched veteran army, and a lecture questioning the will and ability of Cheatham’s Corps to fight anywhere but behind breastworks. Upon viewing the enemy entrenchments, General Cleburne, perhaps the best officer of that rank in the Confederacy, resigned himself to death. Confederate Cavalry commander Nathan Bedford Forest begged Hood to let him take a force around the enemy’s flank and cut them off from Nashville. The leader’s mind was made up. He could not now develop flexibility, an agreement to the counsel of veteran generals, or forgiveness for past failure. The most magnificent display of Southern heroism and suicidal courage would not wait another day.