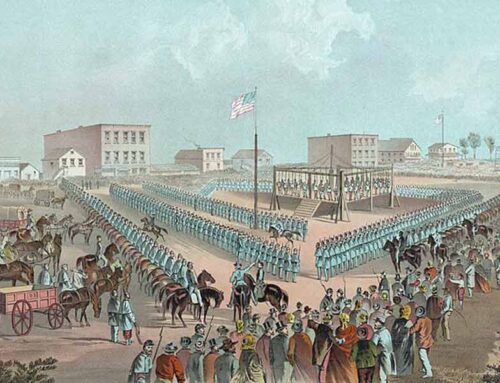

The Sacrifice of Nathan Hale, September 22, 1776

![]() n the wake of brutal defeats that attended the military campaigns of 1778, General George Washington approached a young cavalry officer with an overwhelming appeal to oversee and organize the formation of America’s first spy ring. Young Benjamin Tallmadge was a mild-mannered Yale graduate, an unabashed horse-boy who prized his place in the Connecticut Light Dragoons, a school teacher before the war and the son of a minister. He was an unlikely candidate for the role of operational head of deception and espionage. But Tallmadge was impeccably educated, morally fervent and had a host of childhood connections behind enemy lines that General Washington deeply desired to utilize. The General also had one great ace to play when asking this reluctant young man to consider the post—an appeal to the memory of Tallmadge’s beloved school friend, the recently-martyred Captain Nathan Hale.

n the wake of brutal defeats that attended the military campaigns of 1778, General George Washington approached a young cavalry officer with an overwhelming appeal to oversee and organize the formation of America’s first spy ring. Young Benjamin Tallmadge was a mild-mannered Yale graduate, an unabashed horse-boy who prized his place in the Connecticut Light Dragoons, a school teacher before the war and the son of a minister. He was an unlikely candidate for the role of operational head of deception and espionage. But Tallmadge was impeccably educated, morally fervent and had a host of childhood connections behind enemy lines that General Washington deeply desired to utilize. The General also had one great ace to play when asking this reluctant young man to consider the post—an appeal to the memory of Tallmadge’s beloved school friend, the recently-martyred Captain Nathan Hale.

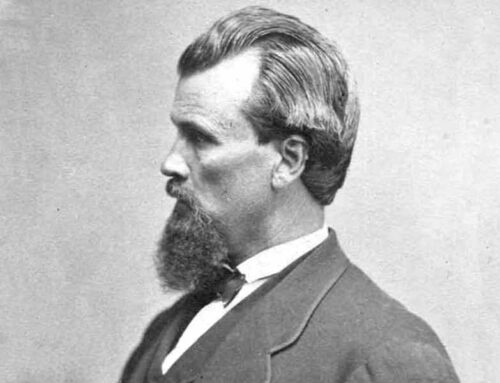

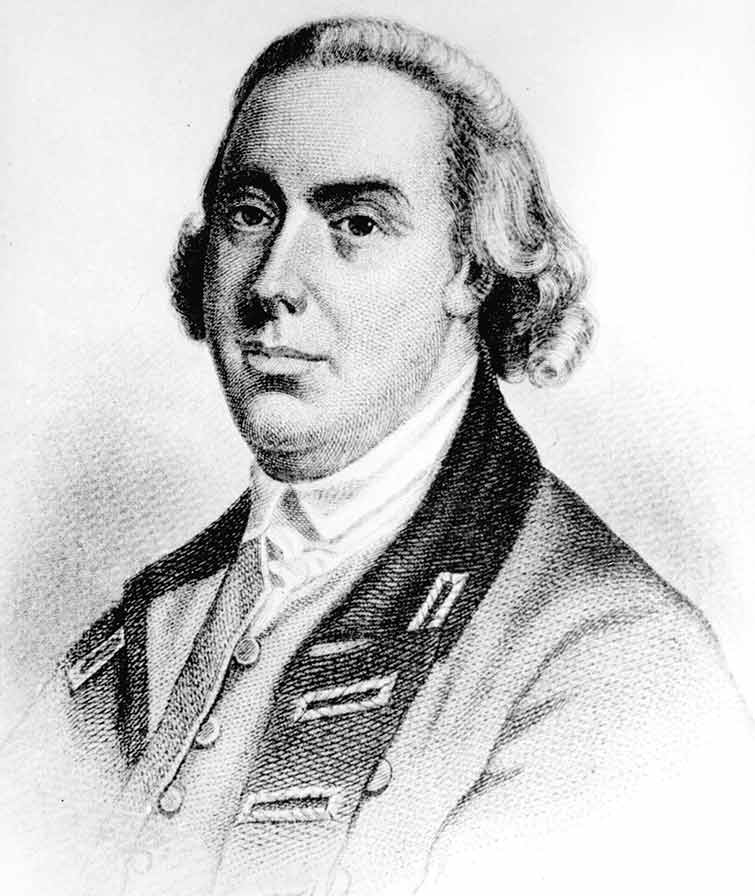

Benjamin Tallmadge (17540-1835) as Major in the 2nd Continental Dragoons

Nathan Hale (1755-1776)

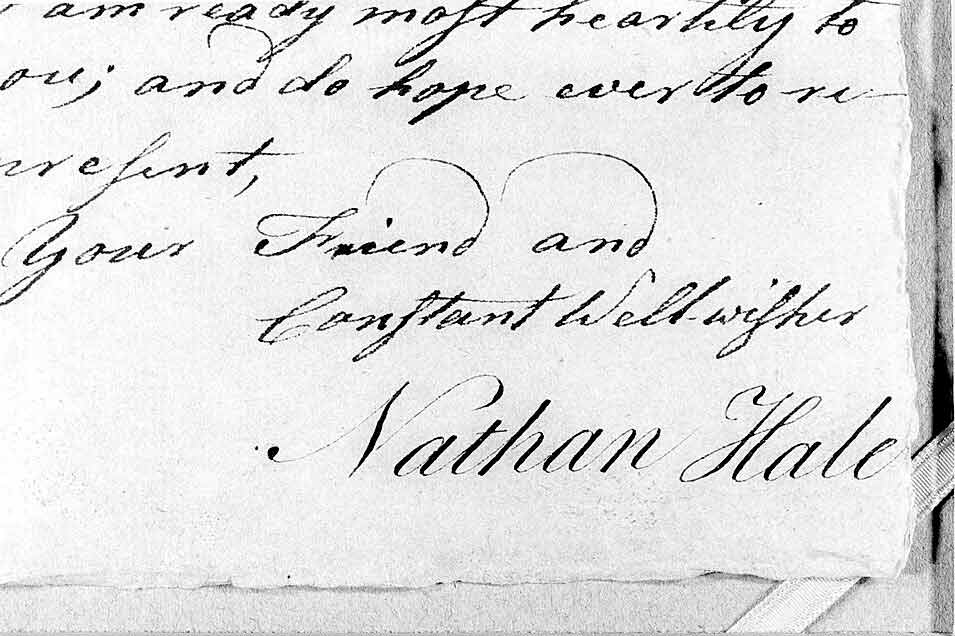

As is common even to this day, a friendship of such force as theirs was cultivated in the halls of learning—in their case, Yale University. Leafing through these friends’ correspondence, it’s still touching to read the prolific use of “I remain your constant friend” and “a heart ever devoted to your welfare.” If anything malicious ever happened to one, the other would be merciless toward his assailants. In those peacetime days, their contests were against haughty seniors and exacting headmasters, but the sentiment thrived.

Nathan Hale’s signature after the affectionate closure of a letter

Both were sons of preachers: Tallmadge was bound to be an educator, Hale was expected to follow his father into the ministry. As was only to be expected of strict New England Congregationalists, both young men were taught to revere magistrates and ministers as God’s chosen servants, and to observe each Sabbath as if it were his final one on this earth. They pronounced grace thrice daily, attended church twice on Sundays, and prayed always before taking to their beds. They joined every debating society the college had to offer—theatrical ones as well—and there they learned their Cicero and Plato, their rhetoric and their logic. There they came in contact with plays such as Joseph Addison’s 1713 play Cato, and its stirring line: “What a pity it is. . . . That we can die but once to serve our country.”

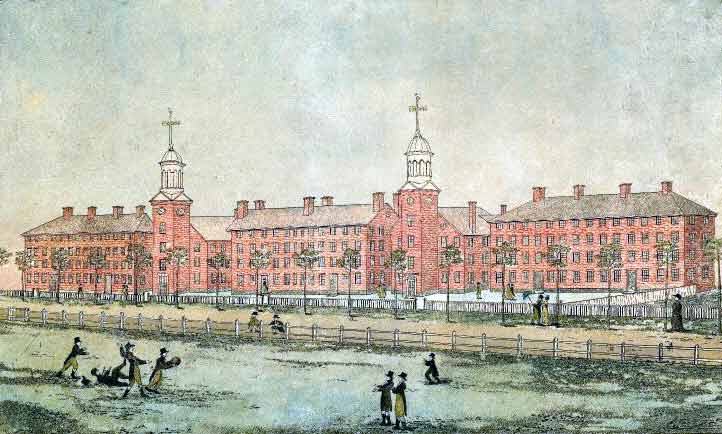

Yale College in 1807

Yale of the 1770s, despite its stringent adherence to protocol and pomposity, was a place where camaraderie flourished and ideas of the time were subjected to the crucible of Biblical thought. Paradoxically, in the minds of modern historians, although perfectly in keeping with those of the Christian tradition, the college inspired a rebellious, insubordinate ethos amongst its students, not the least of which occurred when discussing relations with the Mother Country—England.

General Thomas Gage (1718-1787)

General Thomas Gage, commander of the British forces in North America, branded the place “a seminary of democracy.” Indeed, one of the teachers there, a Reverend Dr. Huntingdon—in between classes on Latin declensions and conjugations—subjected Hale and Tallmadge to a series of rants on the iniquity of the Stamp Act. These rants were digested by his students and presented by them to the debating society, from where they would take the form of printed fuel for the fire and be published as essays. Such is the course of a young patriot sharpening his reason and argument.

Example of a debate club in the 1700s

It was not all bluster and student boycotts against taxation though; they were concerned for domestic matters, too, and were figuring out their personal beliefs for themselves. One amusing incident passed down relates the time Hale and Tallmadge debated the motion: “Whether the Education of Daughters be not, without any just reason, more neglected than that of sons.” They argued for the “pro-daughter” side, and won, an event that James Hillhouse, a Yale contemporary, said “received the plaudits of the ladies present.”

The Nathan Hale Homestead in Coventry, Connecticut—Nathan Hale never lived in the home seen here, as it was built by his parents after his death, but his childhood home was in the same location as the newer, larger home still present

These two friends went home from college to establish lives for themselves. They both became school teachers in corresponding schools only a short distance from each other. Tallmadge tended horses. Hale fell in love. Then came “the shot heard ’round the world.” Militias were called up, the friends joined separately. A war for independence was underway. Of their class of 1773 consisting of thirty-five members, thirteen continued into the ministry while thirteen joined the Continental Army.

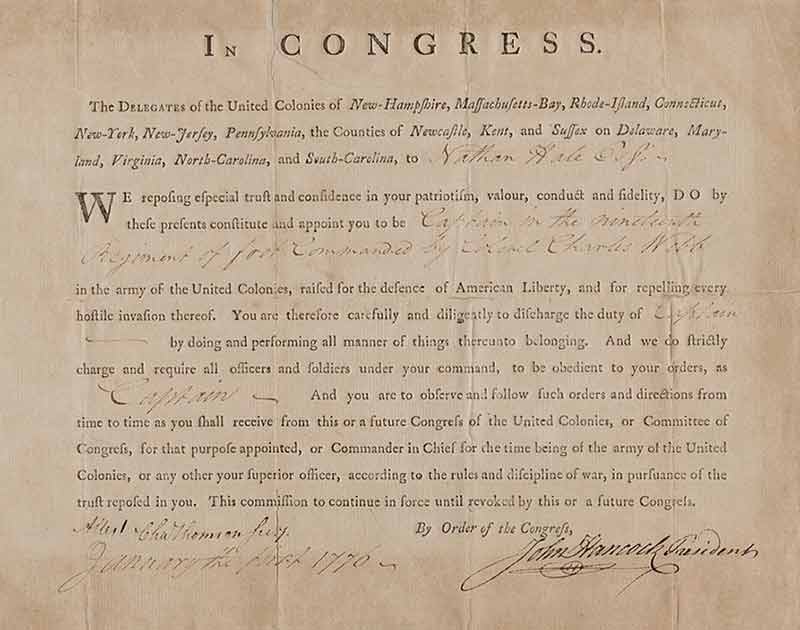

Nathan Hale’s commission as Captain in the Nineteenth Regiment of Foot

When Washington’s army left Boston in 1776 and took up position in New York, Hale and Tallmadge were among his ranks. Hale was distraught over the divided state of the country exhibited by the two-thirds of the city that remained staunch Tories. He wrote to his brother: “it would grieve every good man to consider what unnatural monsters we have, as it were, in our very bowels.” A few days later, the front of General Washington’s army collapsed under an attack by Lord Howe—the battle for Brooklyn had begun, and it would prove disastrous.

Battle of Long Island

Washington and his commanders furiously debated what to do with New York City as they abandoned it. The New Englanders wanted to burn it, so as to leave the British with nothing but a blackened husk in which to spend the approaching winter; the New Yorkers, sensibly enough, were reluctant to raze their own property. Congress made the decision for them, ordering no destruction of property be done; Washington withdrew accordingly.

The Continental Army retreats from New York

This left the Continental Army in a most precarious position, surrounded by British forces under General Howe. Lacking reliable information about the enemy’s strength, positions, and intentions, Washington tasked one of his generals to find him a volunteer who would infiltrate British lines in the guise of a civilian to gather critical data to plan his next move. He needed a spy in a time when the very word was odious to the gentlemanly sensibilities of both sides. Military reconnaissance and scouting were staple roles in both armies, and the captured members of these special forces were treated with the honor of combatants. Washington himself had been such a scout in the French and Indian War. These roles were not seen as that of spying.

George Washington (on horseback) at the Battle of the Monongahela during the French and Indian War

Years later, in 1826, when interviewed by his grandson, an aging Asher Wright recounted:

“Colonel Knowlton of the Rangers, desired for Colonel Sprague, my aunt’s cousin, to go on to Long Island. Sprague refused, along with the rest of them, saying, ‘I am willing to go & fight them, but as for going among them & being taken & hung up like a dog, I will not do it’.”

No soldiers (let alone officers) in Knowlton’s Rangers—the regiment charged with providing Washington with information—wanted to take the ignoble job of secret agent. And it was then, remembered Asher, that “Hale stood by and said, ‘I will undertake the business’.” Washington met with him personally, and Hale’s orders were strictly to spy out Long Island and come home. Yet, within days of being dropped off along the sound of Long Island, Hale was betrayed to Major Robert Rogers by loyalists who recognized him as one of the “patriot Hales of Connecticut.”

Thomas Knowlton (1740-1776) is considered America’s first intelligence professional, and his unit, Knowlton’s Rangers, gathered intelligence during the early War for Independence. Knowlton was killed in action at the Battle of Harlem Heights.

Robert Rogers (1731-1795)

Like Washington, Major Rogers himself was an old veteran and scout of the French and Indian War, and had in fact offered his services to Washington the previous year, hoping to play both sides. Washington knew of Rogers’ unethical reputation and declined his services out of suspicion for his sincerity—and he was right to be suspicious, for within weeks of being spurned, Rogers was receiving a hefty pension, had garnered a promotion, and was given a regiment of Queen’s Rangers to track down patriot informants for General Howe. Rogers would prove a brutal enemy for the Patriots, and his first prey was the ill-fated Nathan Hale.

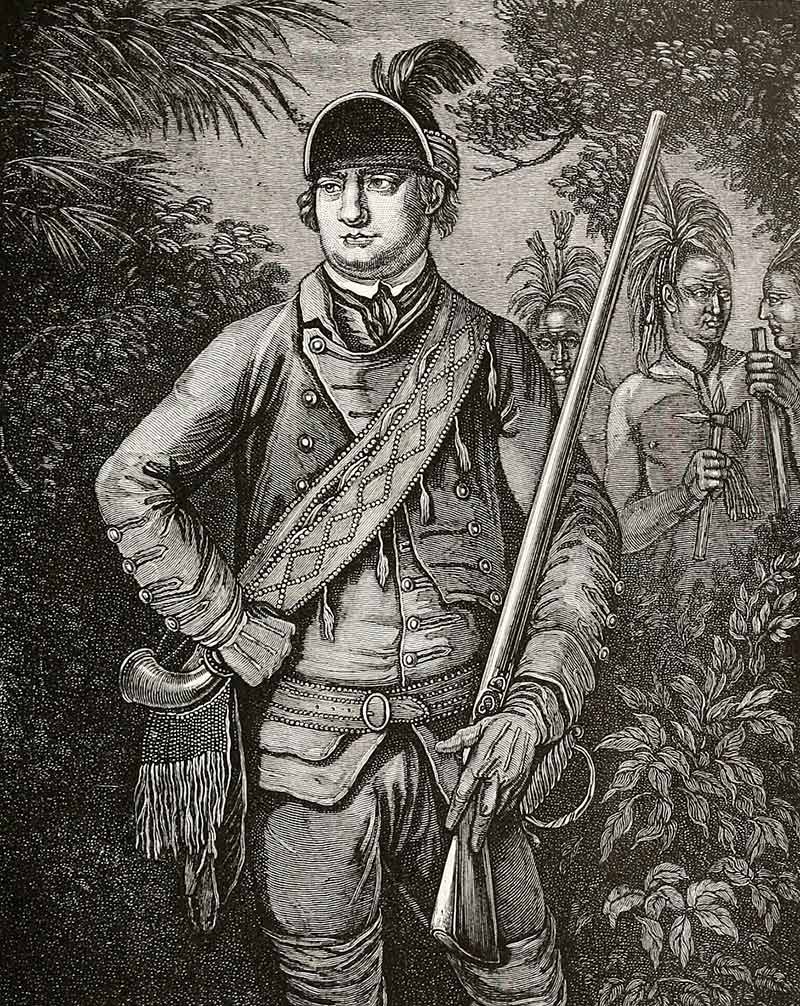

Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe (1752-1806) in the classic green uniform of his unit, the Queen’s Rangers—he would eventually command the unit, when it would become informally known as Simcoe’s Rangers

Rogers befriended the young man, shared numerous meals with him, and proposed that they travel together—all under the pretense of being a fellow patriot caught behind enemy lines. When Hale joined him on the third day for another meal spent together, Rogers sprang his trap and had Hale arrested as a spy, clapped in irons, and his person searched for incriminating documents, of which there were many.

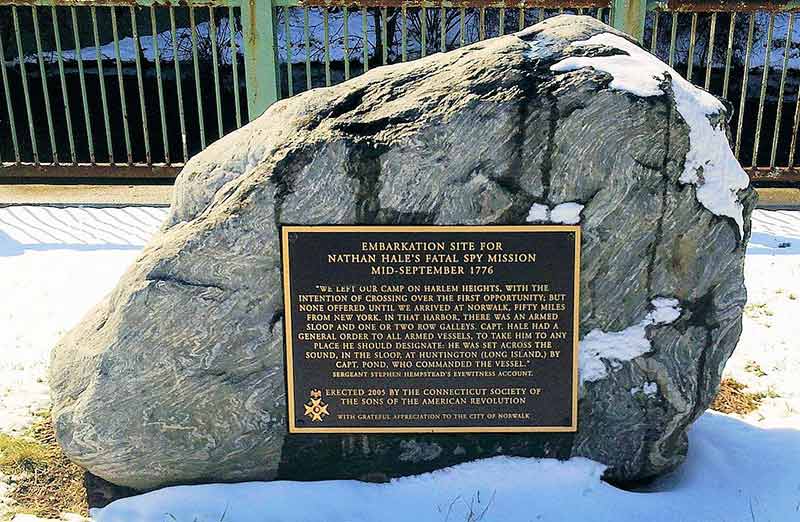

A stone and plaque mark the embarkation point of Nathan Hale’s final mission

Very late the next night, Rogers unceremoniously deposited Hale at General Howe’s headquarters in Manhattan. Deliberation on Hale’s execution for espionage was mere formality. General Howe was in the midst of orchestrating a major battle campaign and had no time to conduct a full court-martial for espionage, even if one had been required. The evidence was blatant and entirely uncontroversial: Rogers had provided witnesses who could attest to Hale’s identity, and others who asserted that he had been sent by Washington; Hale himself had at last admitted that he was an officer in the Continental Army. But, as Hale was captured in civilian clothes behind enemy lines and carrying a sheaf of incriminating documents, there was neither reason nor need for Howe to agonize over this spy. After Howe, roused from his bed, had sleepily signed Hale’s death warrant, the young patriot was placed under the guard of the provost marshal to await his execution.

The greenhouse on the Beekman estate where Nathan Hale was reportedly kept the night before his execution

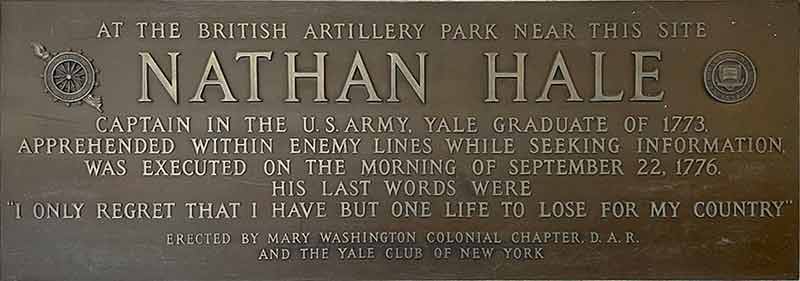

A plaque on the Yale Club building commemorates the execution of Yale alum Nathan Hale

After breakfast, it was time. Hale’s destination was the artillery park, about a mile away, next to the Dove Tavern, at what is now Third Avenue and Sixty-sixth Street in Manhattan. His hands were pinioned behind his back, while a couple of guards led the way. Behind him marched a squad of redcoats with loaded muskets and fixed bayonets. Accompanying the party was a cart loaded with rough pine boards for his coffin.

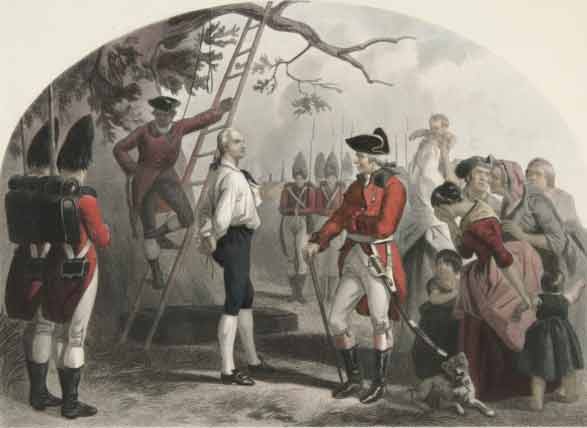

At the site, the noose was rudely swung over a rigid horizontal branch about fifteen feet up, and Hale shakily climbed the ladder that would soon be kicked away for the drop. Next to the tree there was a freshly-dug grave awaiting.

Nathan Hale’s final moments

At the apex of the ladder, Hale was permitted the traditional last words. The only written witness account we have of them comes from the British Captain Frederick MacKenzie, who wrote in his diary for September 22:

“He [Hale] behaved with great composure and resolution, saying he thought it the duty of every good officer, to obey any orders given him by his commander-in-chief; and desired the spectators to be at all times prepared to meet death in whatever shape it might appear.”

The now famous “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country” was lifted from Joseph Addison’s play Cato, once so popular among the Yale graduates, and put into Hale’s mouth many years later by fellow student William Hull, who was not present to witness his death, but knew it to be one of Hale’s favorite lines, and the most likely sentiment animating his friend’s heart in his last moments. Hull was not far wrong, although Hale’s emphasis seemed to have been, as any good Christian’s would be at the hour of death, on exhorting all to be always ready to meet the Great Judge, coupled with a fearless lack of remorse for the course of action which had led to his cruel demise.

A 1925 commemorative Nathan Hale postage stamp

Bronze memorial to Nathan Hale

Hanging is a most awful business, one easily bungled, especially without the presence of a quick-drop platform or an expert at positioning the noose. Still, it was a method that had been cultivated amongst civilized societies to be an instant and tidy form of execution. Hangmen were masters of their grim craft and, in the case of a typical court-martial, an expert would be employed to execute the sentence. No such bare-minimum consideration was afforded Nathan Hale. He was made to climb a ladder which would then be kicked out from under him, a rope was thrown over a nearby branch, and his hangman was a recently freed slave with no experience in minimizing the agony of the executed. These gruesome details are not relayed in any way to distress readers unduly, but they are what reached the ears of Washington, Tallmadge, and Hale’s distraught family when word of his sacrifice spread. They are the ugly realities of the cost exacted of patriotic men and women for our liberty. Hale’s body was left hanging as an example and a deterrent for three days beside a disfigured effigy of Washington, until he was cut down by a slave and buried in the unmarked grave beside the tree. He was twenty-one years old.

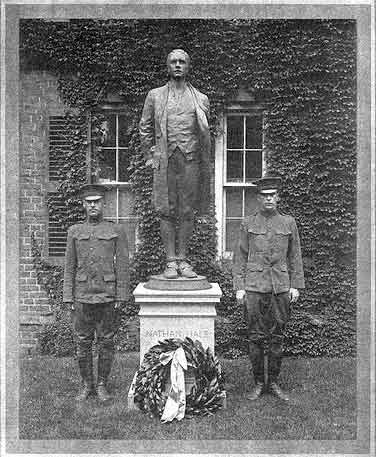

Two Yale servicemen pose beside a statue of Nathan Hale in 1917

George Washington, while a man of admirable mental resolve and a great capacity to endure, was not unaffected by the tragedies of subordinates such as Hale, men who were small in the aggregate, but who represented then, as they do now, the critical component of free societies—a willingness to sacrifice, no matter the cost to reputation or life.

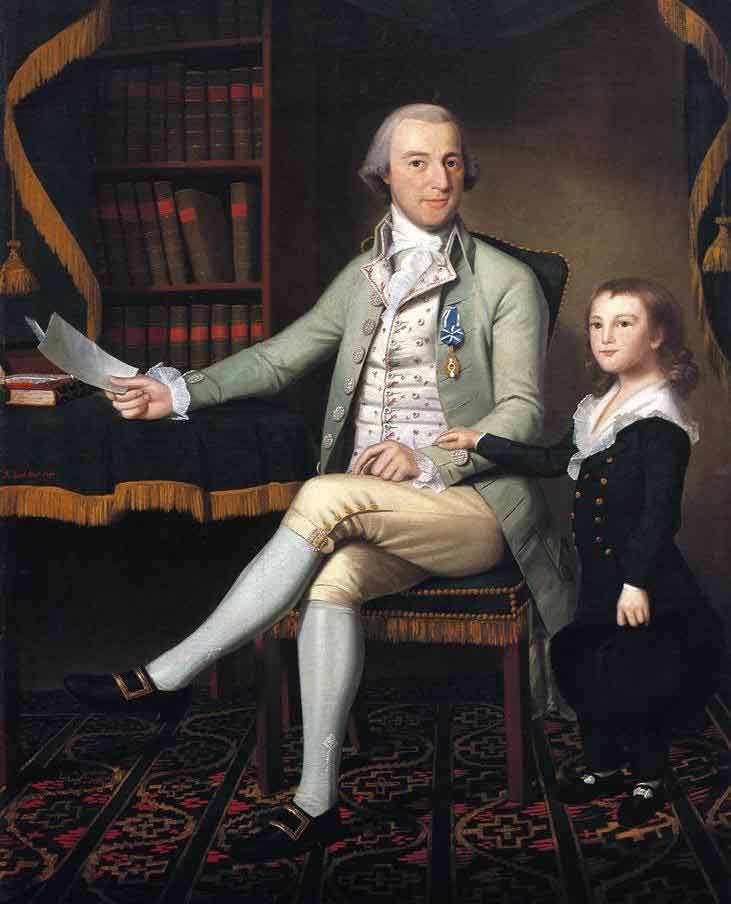

Benjamin Tallmadge in 1790 with his son, William

Our founding times were full of such men. It is why Washington could appeal to Benjamin Tallmadge on the basis of his poor friend to take up the mantle and continue the work, despite so crushing a setback. It is why Tallmadge had the mettle to take his grief and assemble the single most effective spy ring of the war—The Culper Ring—whose collected information quite literally won us the war, and whose airtight secrecy was so great that not even Benedict Arnold’s treachery could sink them, or historians identify them until this century. Benjamin Tallmadge lost one friend in a brutal way, then proceeded to rope in dozens more to shoulder the same risks and carry on the cause. Such is the mindset of those with an eternal vision. Such is the legacy we Americans have inherited.

Image Credits: 1 Benjamin Tallmadge (wikipedia.org) 2 Nathan Hale (wikipedia.org) 3 Hale’s Signature (wikipedia.org) 4 Yale College (wikipedia.org) 5 Thomas Gage (wikipedia.org) 6 1700s debate club (wikipedia.org) 7 Hale Homestead (wikipedia.org) 8 Nathan Hale’s Commission (wikipedia.org) 9 Battle of Long Island (wikipedia.org) 10 Continental Retreat (wikipedia.org) 11 George Washington (wikipedia.org) 12 Thomas Knowlton (wikipedia.org) 13 Robert Rogers (wikipedia.org) 14 John Graves Simcoe (wikipedia.org) 15 Hale Embarkation (wikipedia.org) 16 Beekman Greenhouse (wikipedia.org) 17 Hale plaque (wikipedia.org) 18 Final moments of Nathan Hale (wikipedia.org) 19 Postage Stamp (wikipedia.org) 20 Bronze statue of Nathan Hale (wikipedia.org) 21 Yale Servicemen in 1917 (wikipedia.org) 22 Benjamin Tallmadge (wikipedia.org)