“For the ruthless shall come to nothing and the scoffer cease, and all who watch to do evil shall be cut off, who by a word make a man out to be an offender, and lay a snare for him who reproves in the gate, and with an empty plea turn aside him who is in the right.” —Isaiah 29: 20-21

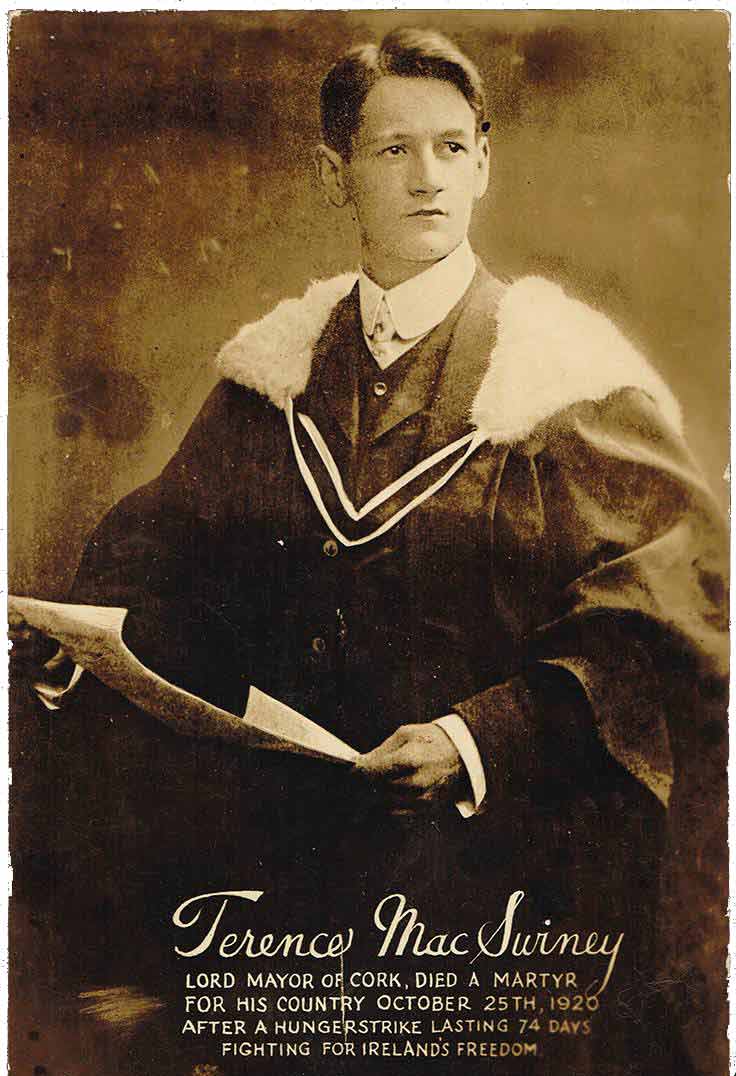

Terence MacSwiney, Lord Mayor of Cork, Died for Irish Freedom, October 25, 1920

ne of the first, most harrowing guerrilla wars of its time was witnessed in the early part of the last century—that of Ireland’s fight to break away from her long occupation by Great Britain. She did this by any means possible, and the incentives were grossly oppressive indeed. Her free press had been abolished, her native language outlawed, her parliament dissolved, and her citizenry kept under martial law. In the midst of such calamitous times, Terence MacSwiney, Irish writer, poet and Republican activist, was elected Lord Mayor of Cork City in the south of the country. He was elected not only by the ballot box but with the blood of his predecessor, Tomás Mac Curtain.

ne of the first, most harrowing guerrilla wars of its time was witnessed in the early part of the last century—that of Ireland’s fight to break away from her long occupation by Great Britain. She did this by any means possible, and the incentives were grossly oppressive indeed. Her free press had been abolished, her native language outlawed, her parliament dissolved, and her citizenry kept under martial law. In the midst of such calamitous times, Terence MacSwiney, Irish writer, poet and Republican activist, was elected Lord Mayor of Cork City in the south of the country. He was elected not only by the ballot box but with the blood of his predecessor, Tomás Mac Curtain.

Terence MacSwiney (1879-1920) in his official robes as Lord Mayor of Cork City, Ireland

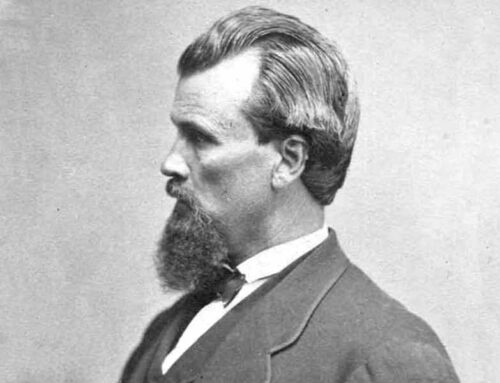

Mac Curtain had been Cork City’s first mayor to be elected by running on a Republican ticket, and he had won it despite the continual suppression of the party’s platform by British authorities. In reprisal for his success, Mac Curtain was gunned down in his own bedroom at dawn by a squad of masked men—later revealed to be Crown Forces in disguise. They had burst into Mac Curtain’s home and fired point-blank into the sleeping mayor as his wife and children cowered nearby. Due to the enforced curfew and martial law, his panicked children risked their lives by running to fetch the doctor for their mortally wounded father. Mac Curtain died in the arms of his pregnant wife who found the soulful courage to remind him “this is for Ireland, Tomás.” It was his thirty-sixth birthday.

Tomás Mac Curtain (1884-1920)

The gory warning cloaked in this assassination was clear: the citizenry of Cork should think twice before electing any more free thinkers. No trial followed; the British Parliamentary inquest blamed “masked and unknown men,” but bragging by local British officials for having orchestrated it fueled outrage. When the Mayor of nearby Limerick was similarly assassinated in front of his family a mere two months later, shockingly the British Parliament agreed it was a perturbing coincidence, but declined further inquiry.

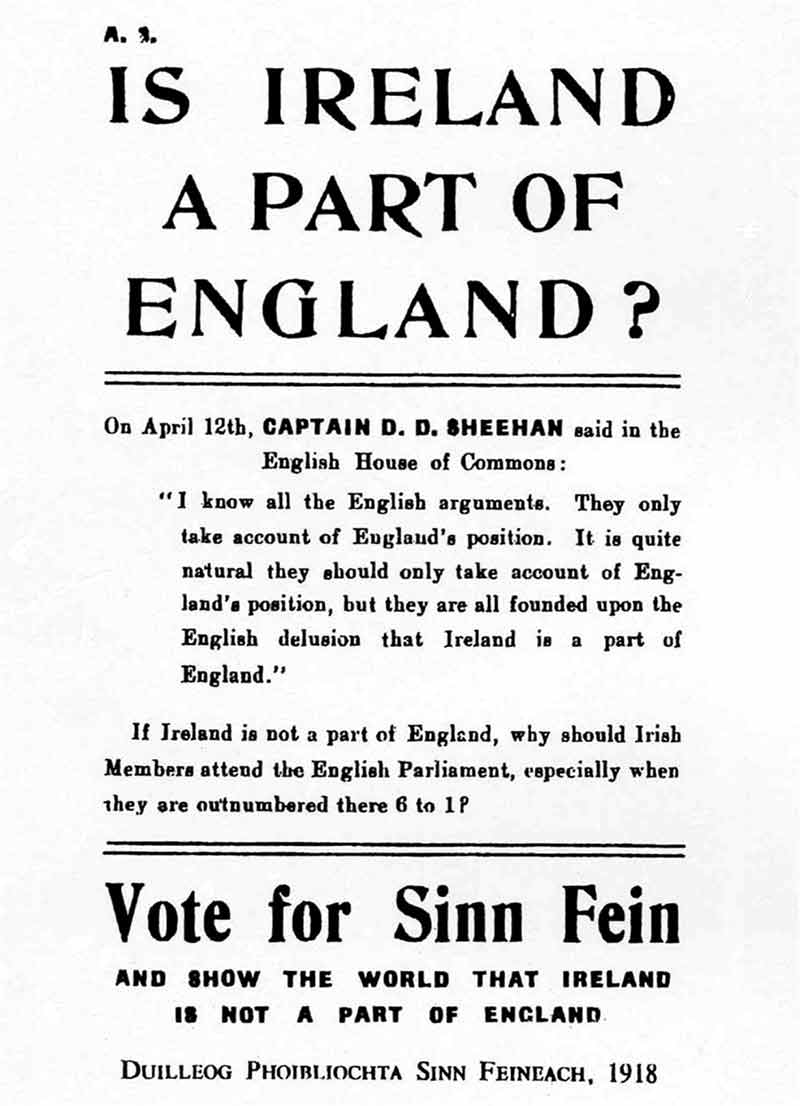

A Sinn Féin election poster from 1918 describing the Irish sentiment towards England’s oppression and underrepresentation of the Irish in the English Parliament

Terence MacSwiney had been Mac Curtain’s close comrade and vice-mayor; he stepped into the role fearlessly when elected and vowed at Mac Curtain’s funeral: “We will not falter. The fight for Irish freedom is our sacred duty.” In a chamber still echoing with grief, he took the oath in March, 1920.

The British struck back swiftly. On August 12, 1920, MacSwiney was arrested at a Republican safehouse, papers in hand that damned him as a plotter of civil unrest. Dragged before a military court, he was tried by court martial despite his elected status, facing vague charges of sedition. “I am not afraid to die,” he told the judge, his voice steady as steel. “Whatever your government may do, I shall be free, alive or dead, within a month.”

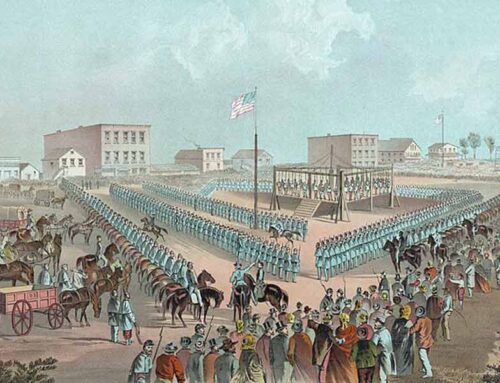

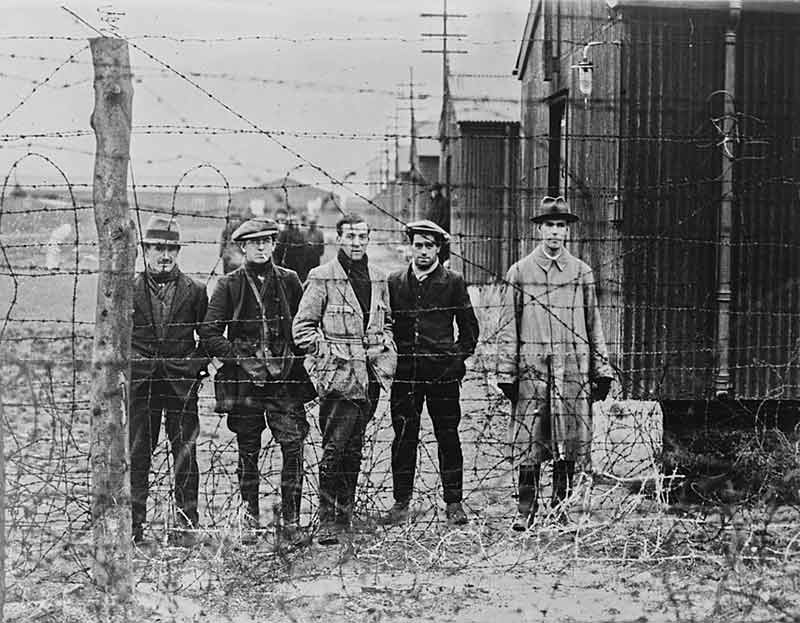

A Sinn Féiner prison camp in Ireland during the 1919-1921 Irish War for Independence

He was shipped to London’s Brixton Prison for incarceration, making a mockery of the supposed justice system in place in his native land. There MacSwiney joined his fellow Irish Republican prisoners on hunger strike, with the aim of demanding Britain acknowledge him and his fellows as political prisoners. This was no new tactic for the Irish, and was met with no mercy at the hands of English guards. With MacSwiney being a duly elected Lord Mayor and the most high-profile striker at Brixton, he became an international celebrity, his emaciated features broadcast in newspapers from Dublin to Delhi. It was of the utmost importance for the British to break his spirit and force a retraction from him; the ordeal proved harrowing. Force-fed through tubes that tore his throat, MacSwiney endured convulsions and delirium, indignities and veiled threats towards the welfare of his wife and infant child. Undaunted herself by these threats, Muriel MacSwiney traveled to London with her baby daughter Máire, pleading for clemency at Westminster’s gates and joining the crowds that swelled outside Brixton Prison, chanting Gaelic hymns to encourage the strikers.

Terence MacSwiney and his devoted wife and political supporter Muriel, likely on the occasion of their marriage in 1917

Prison Brixton, London, England

A lifelong devotee of the Catholic faith, MacSwiney’s historic association of martyrdom as a blessed impetus for change was at odds with his fear of committing the “unabsolvable” sin of his religion—suicide. He wrote letters of explanation and resolve from Brixton, reasoning: “To die for Ireland is not to throw away life, but to give it purpose. We offer ourselves not to end our fight, but to ensure its triumph.”

The world watched in horror: labor unions in Britain appealed for clemency, Indian nationalists drew parallels to their own struggle, the Pope interceded but to no avail. President Woodrow Wilson sent an American Senator as envoy to Ireland to investigate the state of justice in the country. Even King George V personally appealed to Prime Minister Lloyd George’s cabinet to make an exception and release MacSwiney, but the government held firm, branding the prisoners as “republican murderers” unfit for mercy.

Terence MacSwiney on his deathbed

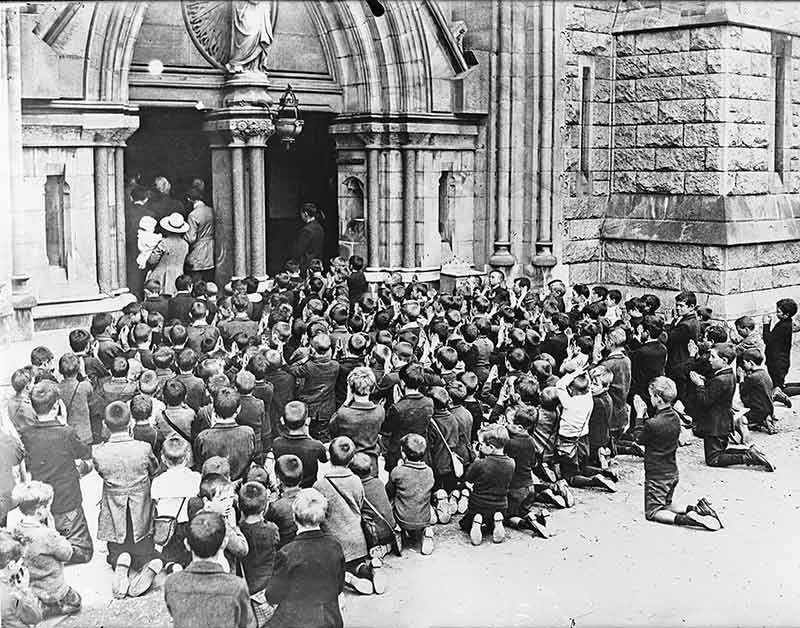

A crowd in Dublin gathers to pray for Terence MacSwiney

On this raw October morning in 1920, as fog clung to the walls of London’s Brixton Prison, Terence MacSwiney, the Lord Mayor of Cork, drew his final breath after 74 days kept as a political prisoner. At age forty-one, the poet-turned-revolutionary slipped away in the arms of his brother and a prison chaplain, his body a skeletal testament to an unyielding will. “It is not those who can inflict the most, but those who can suffer the most who will conquer,” he had written years earlier in his treatise Principles of Freedom. MacSwiney’s death was no quiet surrender; it served as a lurid exclamation mark in Ireland’s gruesome War for Independence, a death that reverberated across the Atlantic. Pictures of MacSwiney’s beautiful widow clutching her infant child upon collecting her husband’s body circulated in papers across the globe, and incited outrage that shamed an empire.

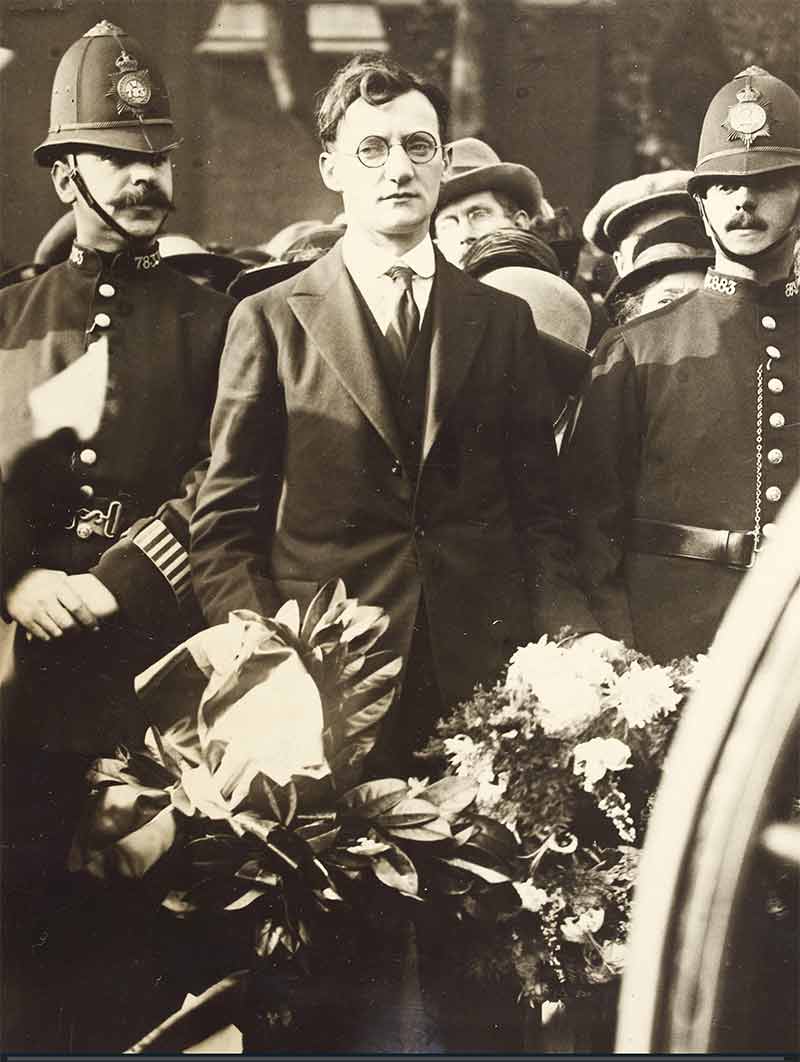

Terence MacSwiney’s brother Seán at the funeral of Terence

The coffin of Terence MacSwiney lies in state at Cork City Hall, Cork, Ireland

In Dublin, trams halted, shops shuttered; in Cork, 100,000 mourned as his cortège wound through streets lined with black crepe. Yet it was across the Atlantic that his sacrifice kindled the fiercest flame. Irish America, with its millions of descendants nursing old grievances, erupted in solidarity. New York City declared a day of mourning on October 26; Broadway theaters dimmed their lights, factories sounded sirens, and at noon, every citizen paused in silence—a “city frozen in grief,” as the New York Times reported. Vigils blazed for weeks: in Boston’s Fenway Park, 50,000 gathered under torchlight, reciting the Rosary; Chicago’s Holy Name Cathedral hosted masses where priests thundered against British “barbarism.” Funds poured in—over $1 million (a fortune then) for the Irish cause, funneled through the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland. In Pittsburgh, 5,000 crammed the Lyceum Theater on Halloween night, 1920, to hear eulogies for MacSwiney. Women’s leagues in Philadelphia sewed Sinn Féin flags; schoolchildren in San Francisco penned letters to Muriel MacSwiney, promising “we’ll fight with words until you win with guns.”

Muriel MacSwiney in 1920

Funeral procession of Terence MacSwiney in Cork

In New York, 200,000 people filled St. Patrick’s Cathedral to mourn him, the largest memorial service the city had seen up to that point. Muriel MacSwiney undertook an overseas voyage to America that December, and while professing she had no strength to do so, she nevertheless went when asked by leaders of the Irish Republican Party. MacSwiney’s sister Min traveled with her. The ladies were hosted by governor Al Smith, as well as given the chance to provide unofficial evidence regarding the dire situation in Ireland before Congressmen belonging to the American Commission on Irish Affairs. Muriel MacSwiney would then become the first woman to be awarded the Medal of Freedom from the City of New York.

Muriel MacSwiney (second from right, holding front sign) takes part in protests during a trip to America

Sinn Féin visits Downing Street, 1921

When MacSwiney’s body was finally released for burial after long political wrangling, it lay in state in London, then at Dublin’s City Hall before sailing home. Buried in his hometown of Cork amid a sea of green, MacSwiney left no grand monument—only a legacy of suffering transmuted into strength. “That we shall win our freedom I have no doubt,” he had mused in prison, “that we shall use it well I am not so certain.” His death hastened the Anglo-Irish Treaty which came about one year later, forcing Britain into peace talks and paving the way to an independent Irish Republic.

Prayer vigil outside the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations, July 1921

Image Credits: 1 Lord Mayor MacSwiney (wikipedia.org) 2 Tomás Mac Curtain (wikipedia.org) 3 1918 Poster (wikipedia.org) 4 Sinn Féiner Prisoners (wikipedia.org) 5 Terence and Muriel MacSwiney (wikipedia.org) 6 Brixton Prison (wikipedia.org) 7 Deathbed portrait (wikipedia.org) 8 Prayer vigil for MacSwiney(wikipedia.org) 9 Séan MacSwiney (wikipedia.org) 10 Lying in state (wikipedia.org) 11 Muriel in 1920 (wikipedia.org) 12 Funeral procession (wikipedia.org) 13 Muriel protesting (wikipedia.org) 14 Sinn Féin visits Downing Street (wikipedia.org) 15 Prayer vigil for Anglo-Irish Treaty (wikipedia.org)