“l have been young, and now am old, yet l have not seen the righteous forsaken or His children begging for bread. He is ever lending generously, and His children become a blessing.”

—Psalm 73: 25-26

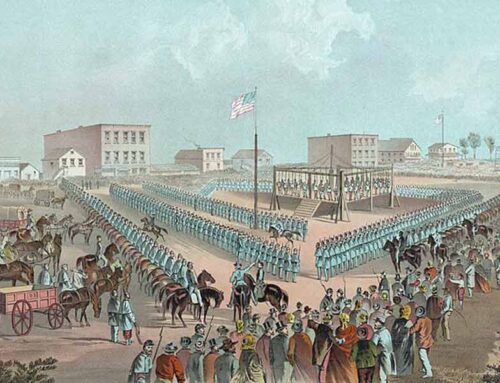

Hudson Taylor’s Holy Ambition, November 18, 1857

![]() he great British missionary, Hudson Taylor, established his China Inland Mission in 1865, on the premise that it would never solicit funds but simply trust God to supply its needs. While this stringent policy may not be appropriate for every ministry, it provided Hudson Taylor with thousands of examples of God’s faithfulness: examples he was faithful to record for posterity—that includes us—so that we might marvel and take heart that we serve a most generous Lord.

he great British missionary, Hudson Taylor, established his China Inland Mission in 1865, on the premise that it would never solicit funds but simply trust God to supply its needs. While this stringent policy may not be appropriate for every ministry, it provided Hudson Taylor with thousands of examples of God’s faithfulness: examples he was faithful to record for posterity—that includes us—so that we might marvel and take heart that we serve a most generous Lord.

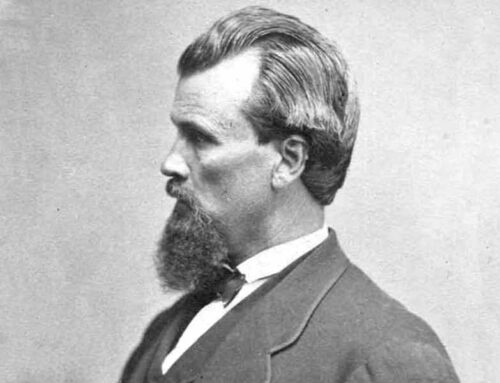

Hudson Taylor (1832-1905), photographed in 1893

This policy was not enacted by some naïve, overzealous babe in Christ—no indeed, by the time of his establishment of the Inland Mission in 1865, Hudson Taylor had been faithfully ministering in China for over ten years. During this time his health had been broken, he was forced to navigate various rebellions and wars, and was at times condemned by fellow missionaries for assimilating into Chinese culture through clothing and tradition. None of this deterred him in the slightest from his ultimate aim—to spread the Gospel of Jesus Christ in China, far beyond her frequented port cities and into her interior.

Barnsley, Yorkshire, England, hometown of Hudson Taylor

Taylor himself had been born in Barnsley, England, to devout Methodist parents who prayed from his infancy that he would serve as a missionary. A sickly child who trained as a medical assistant to prepare for the field, Taylor initially doubted his parents’ faith, but then underwent a profound conversion at the age of seventeen and fearlessly dedicated his life to the service of his Creator.

Just as his parents had once prayed, a divine call to evangelize the vast, benighted regions of pagan China seized Taylor and in 1853, at the intrepid age of twenty-one, he sailed for Shanghai. He was sponsored by the English-based Chinese Evangelization Society, and arrived amid the chaos of the Taiping Rebellion. As is the case with so many of our evangelizing forbearers, Taylor’s first act of business in the port city of Ningbo was to open a hospital, thus giving back to the community he sought to ingratiate himself into. Over the next seven years, Taylor preached, distributed tracts, married Maria Dyer and faithfully ran the hospital—mostly without the promised funds from England.

Hudson Taylor at the age of 21

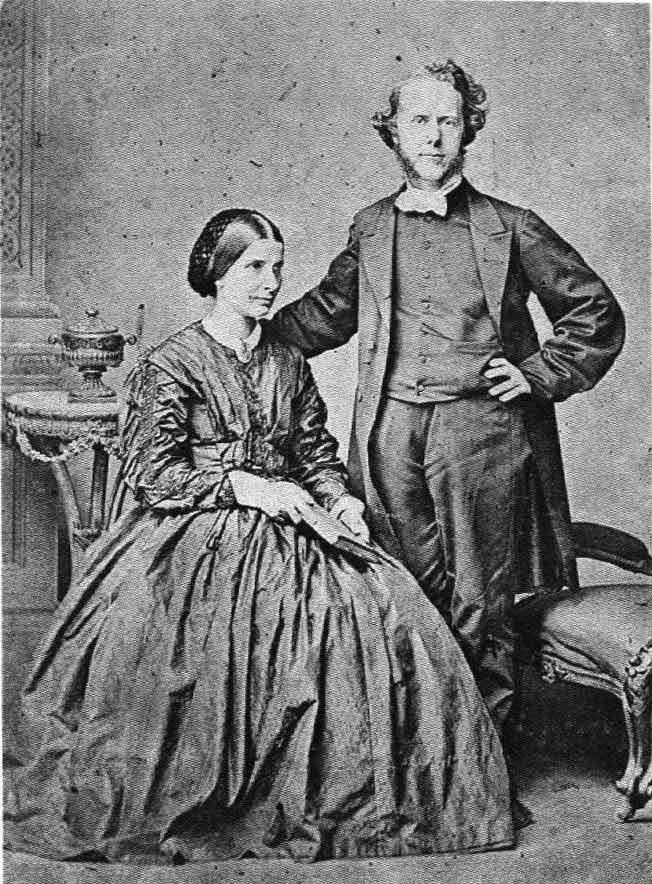

Hudson Taylor and his first wife, Maria photographed in 1865

In 1860 he was forced to return to England for a furlough, after almost succumbing to a life-threatening liver infection after repeated attacks of hepatitis. In London, Taylor struggled with guilt over leaving the mission field despite this health emergency. He also reflected on his ties to the various missionary societies, including that with the Chinese Evangelization Society, with whom he had broken partnership earlier, and who had not supplied his full sponsorship in China. During this furlough, Hudson Taylor said he had a “heavenly vision” on Brighton Beach, where he surrendered all his doubts and committed to a new vision for inland evangelization that would be supported by God’s provision alone.

In his own words, Taylor’s “holy ambition” was to penetrate China’s eighteen inland provinces, long neglected by coastal-focused missions. For this cause in 1865, he founded the China Inland Mission with no fixed salaries, relying solely on prayer for support, and governed from China rather than a distant board.

The “Lammermuir Party”, photographed in 1866—Hudson Taylor is seated, center, with his wife Maria to the right of him, each holding one of their children. The four children pictured are all theirs. After Maria’s death in 1870, Taylor would then marry Jennie Faulding, who is seen here seated to the left of Taylor.

Recruiting twenty-four missionaries, he led the “Lammermuir Party” back to China in 1866, establishing mission stations amid famine, riots, and threats by those natives who resented Christian and imperial influence. Taylor insisted all his workers dress and live as locals to foster trust and enable evangelism. Despite suffering severe personal losses—four of his children died young, as did his beloved first wife—he recruited over 800 missionaries to share in the task, emphasizing, “let us in everything not sinful, become like the Chinese, that by all means we may save some.”

In all this, his Lord provided. By the time of Taylor’s death in 1905, the Inland Mission project had become the world’s largest Protestant mission agency, with 125 schools, 18,000 converts, and churches in even the remotest of regions. To this day, Taylor’s legacy endures in China’s underground church boom, a testament that no culture is too far gone for redemption, and a defense of Taylor’s unyielding belief that “the Great Commission is not an optional suggestion but a command.”

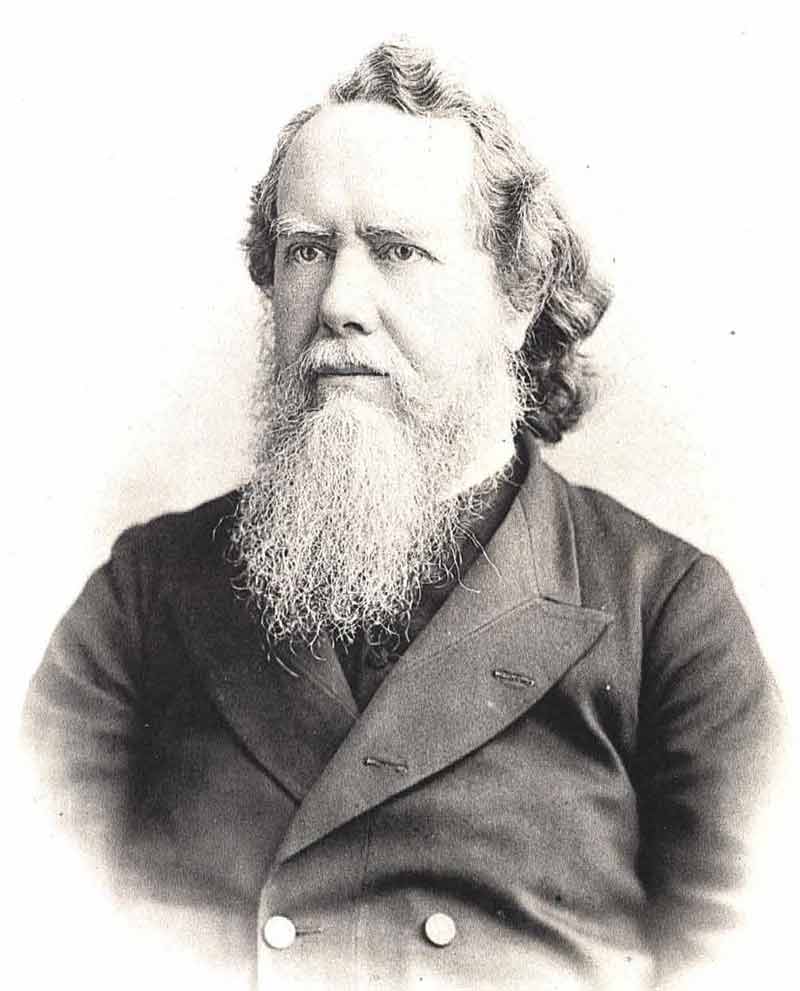

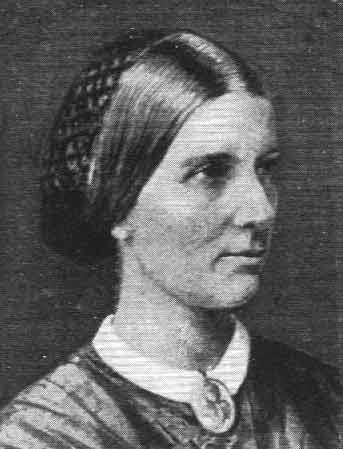

Maria Dyer, Hudson’s first wife (1837-1870)

Jennie Faulding, Hudson’s second wife (1843-1904)

On November 18, 1857, at the start of his ministry, a young Hudson Taylor penned a letter which would immortalize the trust he put in his God to provide. The holy ambition displayed in it would continue to animate him until the very end of his life when he would be buried beside his first wife in the land he had sought to claim for Christ.

Many seem to think I am very poor. This is true enough in one sense, but I thank God it is “as poor, yet making many rich.” My God shall supply all my needs; to him be the glory. I would not, if I could, be otherwise than I am—entirely dependent myself upon the Lord, and used as a channel of help to others.

On Saturday we supplied, as usual, breakfast to the destitute poor, who came to the number of 70. Sometimes they do not reach 40, at other times exceeding 80. They come to us every day, Lord’s Day excepted, for then we cannot manage to attend to them and get through all our other duties, too.

Well, on that Saturday morning we paid all expenses, and provided ourselves for the morrow, after which we had not a single dollar left between us. How the Lord was going to provide for Monday we knew not; but over our mantelpiece hung two scrolls in the Chinese character—Ebenezer, “Hitherto hath the Lord helped us”; and Jehovah-Jireh, “The Lord will provide”—and He kept us from doubting for a moment. That very day the mail came in, a week sooner than was expected, and Mr. Jones received $214. We thanked God and took courage. On Monday the poor had their breakfast as usual, for we had not told them not to come, being assured that it was the Lord’s work, and that the Lord would provide. We could not help our eyes filling with tears of gratitude when we saw not only our own needs supplied, but the widow and the orphan, the blind and the lame, the friendless and the destitute, together provided for by the bounty of Him who feeds the ravens.

—Hudson Taylor, November 18, 1857 in a letter to his sister, Amelia Hudson Taylor

The China Inland Mission headquarters in Shanghai, China in the late 1800s

Image Credits: 1 Hudson Taylor in 1893 (wikipedia.org) 2 Barnsley, Yorkshire, England (wikipedia.org) 3 Taylor age 21 (wikipedia.org) 4 Hudson and his wife Maria (wikipedia.org) 5 The Lammermuir Party (wikipedia.org) 6 Maria Dyer Taylor (wikipedia.org) 7 Jennie Faulding Taylor (wikipedia.org) 8 China Inland Mission Headquarters (wikipedia.org)