Ellis Island Immigration Station Opens, 1892

“And it shall be when your son asks you in time to come, saying, ‘What is this?’ then you shall say to him, ‘With a powerful hand the LORD brought us out of Egypt, from the house of slavery.’” —Exodus 13:14

Ellis Island Immigration Station Opens, January 1, 1892

![]() n December, 1891 seventeen-year-old Annie Moore of County Cork, climbed aboard the USS Nevada, along with her two younger brothers, in Queensland, Ireland (now known as Cobh). On January 1, 1892 they disembarked to join their parents in New York, the first of seven hundred new immigrants to enter the United States through Ellis Island, formerly considered part of New York but declared by a judge, New Jersey-owned in 1998. By the year of its closure in 1954, more than twelve million more would follow Annie through the portals of the reception area to become United States citizens. The last was a Norwegian merchant-seaman named Arne Peterson.

n December, 1891 seventeen-year-old Annie Moore of County Cork, climbed aboard the USS Nevada, along with her two younger brothers, in Queensland, Ireland (now known as Cobh). On January 1, 1892 they disembarked to join their parents in New York, the first of seven hundred new immigrants to enter the United States through Ellis Island, formerly considered part of New York but declared by a judge, New Jersey-owned in 1998. By the year of its closure in 1954, more than twelve million more would follow Annie through the portals of the reception area to become United States citizens. The last was a Norwegian merchant-seaman named Arne Peterson.

View of Ellis Island in Upper New York Bay with Lower Manhattan in the background

In the years prior to 1892, New York City had processed immigrants through Castle Garden Immigration Depot, perhaps as many as eight million people. There were other ports of entry along the eastern and western seaboards, but the state system was collapsing when the Federal government took control of immigration in 1890. They consolidated the approved entryways and funneled the steerage passengers (1st and 2nd class could be processed aboard ship and disembark directly on Manhattan) through Ellis Island. They conducted a landfill project, doubling its size to six acres and constructed a processing station, which opened the first day of 1892.

An immigrant family in the baggage room of Ellis Island Immigration Station, 1905

The first Ellis Island immigrant station, opened on January 1, 1892 was completely destroyed by fire on June 15, 1897

The second Ellis Island immigration station, as seen in this 1905 photograph, opened on December 17, 1900

The new immigrants came from all the nations of Europe, with noticeable increases from lands of Southern Europe and Russia. Approximately one million arrived every year from 1905-1912. In 1924 Congress passed the Immigration Act, greatly reducing the number of immigrants allowed in and moving much of the processing overseas at the U.S. embassies. They established quotas, seeking to reduce the number of people entering the United States, especially Jews, Italians, and Slavs from Southern and Eastern Europe. The American Eugenics movement played a role in persuading Congress to assist in keeping out people they considered defective or undesirable.

Footage showing immigrants disembarking from a steam ferryboat, July 9, 1903

Newly arrived immigrants await inspection at the Ellis Island Immigrant Building, 1904

Part of the regular processing of new immigrants, culled from their ranks those with communicable diseases, those who were foreign criminals escaping law enforcement, and the obviously indigent who were not considered able-bodied or did not possess enough money to get a new start in the United States. A fairly rigorous medical inspection sent about 2% of the passengers back to their port of origin. About three thousand died in the Ellis Island hospital during the years of the Island’s operation. Estimates of the number of Americans descended from immigrants who passed through Ellis Island range up to one hundred million people.

Aerial view of Ellis Island with the Statue of Liberty and Liberty Island in the foreground, downtown Jersey City on the left and Manhattan, mostly out of view, on the right

After about thirty two years of operation, with the controversial Immigration Act, the use of Ellis Island as port of entry declined. By the 1930s it was used primarily for detention and deportation processing and for POWs of the Second World War. Today, a museum on the island interprets the history of immigration in the United States, especially as it relates to Ellis Island. While foreigners entering the United States to settle also occurred through other ports, Ellis Island has become the symbolic place for people fleeing persecution, poverty and hopelessness to seek a new life of freedom in the United States — to work hard and create a healthier and more prosperous future for their families.

Immigrants bound for Ellis Island approach New York City, with the Statue of Liberty in the background

Memorial to Annie Moore and her siblings in Cobh, County Cork, Ireland

There is a lovely statue in the town of Cobh of Annie Moore and her little brothers, with their bundle and hope, leaving to join their parents who preceded them to New York. They are an appropriate symbol themselves of those whom Providence would bring to these shores to continue the building of a nation unlike any other in history. Think of how God brought your forebearers here and eventually established your family to serve God and raise up new generations.

Image Credits: 1 Ellis Island and Lower Manhattan (Wikipedia.org) 2 Immigrant family (Wikipedia.org) 3 First Station (Wikipedia.org) 4 Second Station (Wikipedia.org) 5 1903 Ellis Island footage (Wikipedia.org) 6 Inspection (Wikipedia.org) 7 Ellis Island and Liberty Island (Wikipedia.org) 8 Immigrants aboard ship (Wikipedia.org) 9 Annie Moore memorial (Wikipedia.org) 10 Ellis Island (Wikipedia.org)

hese are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.”

hese are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.”

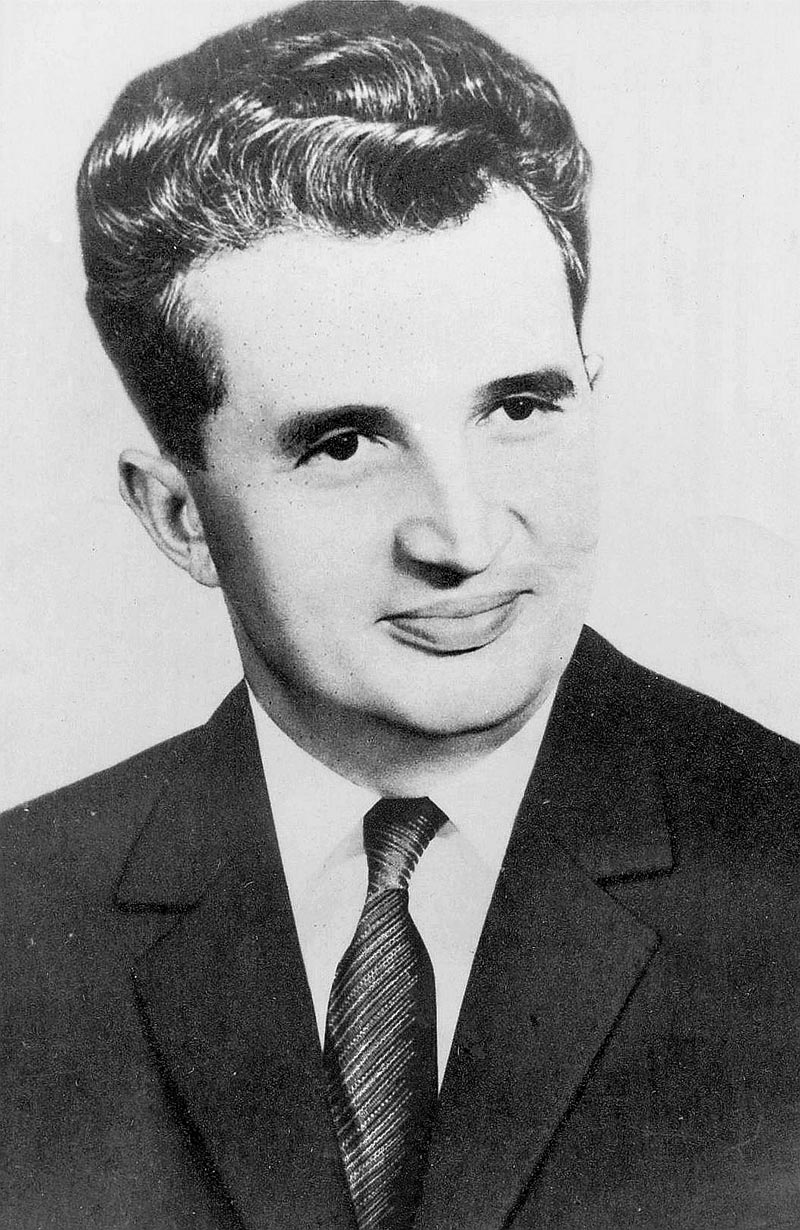

ictators have a long and storied history of leaving this mortal world well before their demographics might suggest, due to their unbridled tyranny. Nicolae Ceauşescu, “President” of Romania, is a good case in point. His downward mortality arc began with an evangelical pastor, László Tőkés of the Reformed Church of Romania, standing athwart history calling, Stop!

ictators have a long and storied history of leaving this mortal world well before their demographics might suggest, due to their unbridled tyranny. Nicolae Ceauşescu, “President” of Romania, is a good case in point. His downward mortality arc began with an evangelical pastor, László Tőkés of the Reformed Church of Romania, standing athwart history calling, Stop!

ew York City in the 19th Century probably surpassed all others in political corruption and depraved popular culture; often the two were bound up together. One aspect of that depravity related to the extent and popularity of abortion, especially among the wealthier inhabitants. According to New York law, abortion was legal prior to “quickening,” that is, before a woman’s awareness of fetal movement. Since 1828, after about the fourth month of pregnancy, a person found guilty of performing an abortion could be charged with second-degree manslaughter, which carried a hundred dollar fine or a year in jail. The queen of abortion providers was an English immigrant, Ann Trow Lohman, known professionally as Madame Restell. In the mid-1840s, one of her chief antagonists was a young widow named Leslie Printice.

ew York City in the 19th Century probably surpassed all others in political corruption and depraved popular culture; often the two were bound up together. One aspect of that depravity related to the extent and popularity of abortion, especially among the wealthier inhabitants. According to New York law, abortion was legal prior to “quickening,” that is, before a woman’s awareness of fetal movement. Since 1828, after about the fourth month of pregnancy, a person found guilty of performing an abortion could be charged with second-degree manslaughter, which carried a hundred dollar fine or a year in jail. The queen of abortion providers was an English immigrant, Ann Trow Lohman, known professionally as Madame Restell. In the mid-1840s, one of her chief antagonists was a young widow named Leslie Printice.