“When He opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the testimony which they held. And they cried with a loud voice, saying, “How long, O Lord, holy and true, until You judge and avenge our blood on those who dwell on the earth?” Then a white robe was given to each of them; and it was said to them that they should rest a little while longer, until both the number of their fellow servants and their brethren, who would be killed as they were, was completed.” —Revelation 6:9-11

The Legacy of Martyred Sir John Oldcastle, the Original Falstaff, December 15, 1417

![]() istorical fiction has, over the centuries, maintained both its popularity and also its extreme influence on how actual historical events are remembered in the public consciousness. Whether it be Homer’s dramatization of ancient conflicts, or Virgil’s weaving of a founding myth for Roman civilization, or Harriet Beecher Stowe’s divisive powder keg of a novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, to more recent works like the Left Behind series that fundamentally changed an entire generation’s interpretation of the end times: the power of fiction based on fact is enduring.

istorical fiction has, over the centuries, maintained both its popularity and also its extreme influence on how actual historical events are remembered in the public consciousness. Whether it be Homer’s dramatization of ancient conflicts, or Virgil’s weaving of a founding myth for Roman civilization, or Harriet Beecher Stowe’s divisive powder keg of a novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, to more recent works like the Left Behind series that fundamentally changed an entire generation’s interpretation of the end times: the power of fiction based on fact is enduring.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

In their own time, Shakespearean plays pioneered a form of wholesale historical dramatization—and at times revision—of past events that remains the accepted version for many of us to this day. Whether William Shakespeare was indeed a real man, or simply the alias of a more formidably-educated and politically-motivated nobleman, is a theory to be explored another day. What is an undisputed fact is that the man behind these plays was a genius and throughly intentional in his use of entertainment to reveal political truths and sway public opinion.

But cleverer still than all that, I think, are the ways in which Shakespeare wove in side characters, figures who mirrored real life supporting characters of great events. He often changed their names or tweaked their motivations, but his incorporation of these more minor personages displays his acceptance of their impact on events, as well as his deep knowledge of his subject.

A parade of Shakespeare’s characters, many based on real people

One such supporting character he named Falstaff. This knight appears in what is often referred to as Shakespeare’s “Henriad”—a series of plays detailing the reigns of Henrys the IV, the V and the VI of England, with an errant Richard II thrown into the middle. Falstaff appears therein as an uncouth, cowardly and entirely disreputable companion of a young King Henry V, in the eponymous play Henry V—best remembered for its rousing speech in which Shakespeare coined the phrase, “we few, we happy few, we band of brothers!”.

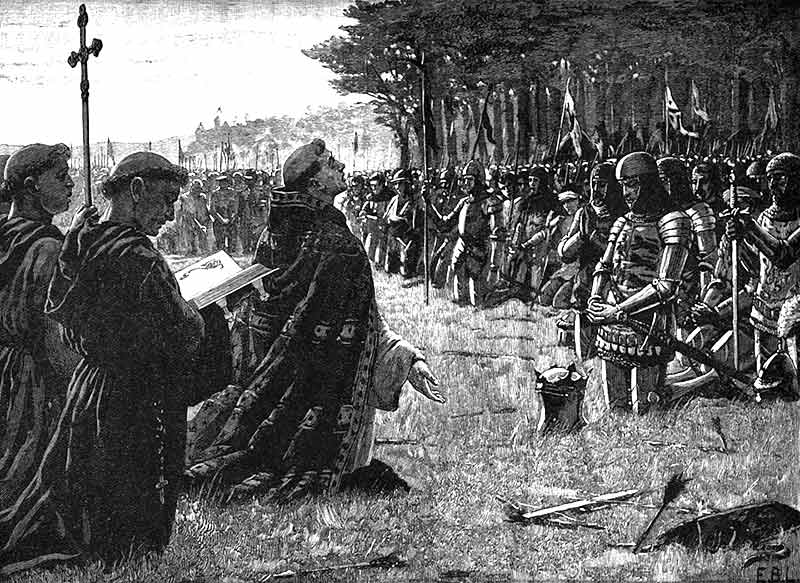

The Thanksgiving Service on the Field of Agincourt by Edmund Blair Leighton portrays King Henry V and his men giving thanks at Agincourt—it was the precursor to this same battle that Shakespeare memorialized via King Henry’s rousing “we few, we happy few, we band of brothers!” speech

The “real” man on whom Falstaff was based was actually a Sir John Oldcastle of Cowling Castle. In fact, in his original drafts of the play, Shakespeare used Oldcastle’s name, but such was the outrage of Oldcastle’s surviving relations regarding his plans to portray their ancestor as a corrupting sidekick, that the playwright was forced to come up with the alias “Falstaff” instead.

Shakespeare’s Falstaff character in a tavern with a young future King Henry V

The real Sir John was indeed a royal favorite of Henry V, but also a follower of John Wycliffe, both members of a religious sect called Lollards by their opponents. Sir John Oldcastle’s ardor in the cause of equipping the common Englishman with a Bible in his native tongue, and the price he later paid for it, led to him being considered the first martyr for Christ among England’s nobility.

The remaining entrance gate of Cowling (or Cooling) Castle

Sir John rises to prominence in historical accounts at the time of his marriage into nobility in 1409, after having distinguished himself in various Tudor wars fought in Wales and Scotland. It was during these campaigns that he grew close with a young Prince Hal, who would later become the legendary Henry V. Once a member of the nobility, Sir John took his seat in the House of Lords, and there exercised his patronage of those followers of Wycliffe who sought to reform the church. No such ecclesiastical reform has ever been undertaken by the people of God without a political consequence resulting, and so Wycliffe’s Lollards were considered a great threat by the establishment.

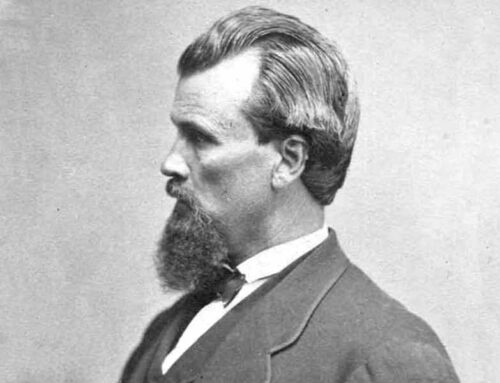

John Wycliffe (1328-1384)

In Sir John’s time, the persecution of the Lollards had grown so commonplace that the first law passed in England allowing for the burning of a criminal was in the case of burning these “heretics” for their religious sentiments. Despite such adverse conditions, Sir John Oldcastle had many copies of Wycliffe’s writings copied and circulated throughout Canterbury, Rochester, London and Hertford. If any Lollard preacher was forbidden to preach or was arrested, Oldcastle would advocate and protect him—and King Henry V in turn protected his old friend. Sir John also reached out to fellow believers in Europe, and thus created an international community espousing the doctrines of Christ Alone put forth by Wycliffe and Hus.

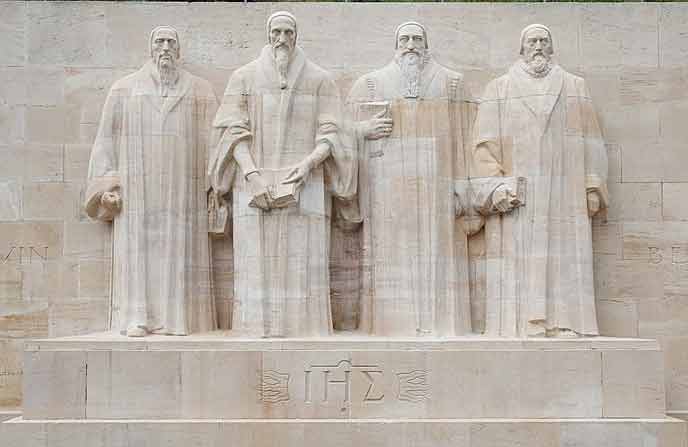

Housed on the grounds of the University of Geneva in Geneva, Switzerland, the International Monument to the Reformation—more commonly called Reformation Wall—depicts William Farel, John Calvin, Theodore Beza, and John Knox, among other key historical characters

In response to his fearless convictions, the established clergy set about to convince King Henry that his old friend was the motivating drive behind an international conspiracy targeting the Church and the King—the wicked have no new tactics, the playbook remains familiar. King Henry then sent for Sir John and pleaded with him personally to explain himself and recant his heretical stances regarding the corruption of the clergy and the authority of the pope. Sir John told his liege that he had been willing and desirous to obey him in all things, but this he could not do. Being thus rebuffed, the king banished Sir John back to his abode at Cowling Castle.

The clergy were undeterred and soon summoned Sir John to trial, going so far as to forge a decree from the king for him to be examined and punished as they saw fit. Thus, in 1413, under false pretenses, Sir John Oldcastle was put on trial by the ecclesiastical court where he refused to recognize papal authority over the Scriptures. When the court demanded a confession from him, he instead confessed aloud to God in their midst, saying “I confess to Thee, O God! and acknowledge that in my frail youth I seriously offended Thee by my pride, anger, intemperance, and impurity: for these offenses I implore thy mercy!” Then to the court he said, “I ask not your absolution: it is God’s only that I need.” When the sentence of death was read out, Sir John said, “It is well, though you condemn my body, you can do no harm to my soul by the grace of my eternal God.”

The entirety of the Tower of London complex as it stands today within London

For this he was summarily excommunicated and condemned to death as a heretic, but the king granted him a stay of execution for forty days, hoping he would recant. During that time Sir John was imprisoned in the Tower of London, but in a mysterious providence, he managed to escape before his execution and took refuge in Wales, sheltered by his fellow Lollards in the land he had once helped King Henry to subdue. There he is believed to have led an armed revolt, although the corrupted history of the time—as is made apparent by the previous false accusations made against him—casts doubt on the likelihood of this being true. Nevertheless, it is now referred to as Oldcastle’s Revolt and the version of it told to King Henry estranged the two friends forever.

The White Tower—the oldest standing portion of the Tower of London—dates from 1078 and was built by William the Conqueror

King Henry V (1386-1422)

The freedom he enjoyed in Wales did not last. Sir John Oldcastle was recaptured after a span of four years on the run, and taken back to London to serve his previous sentence. This time King Henry, being absent due to continuing his conquest of France, did not intervene. Before his execution Sir John proclaimed to the gathered mob:

“. . . I suppose this fully, that every man in this earth is a pilgrim toward bliss, or toward pain; he that knoweth the holy commandments of God, and keepeth them to his end, he shall be saved, though he never in his life go on pilgrimage, as men now do, to Canterbury, or to Rome, or to any other place.”

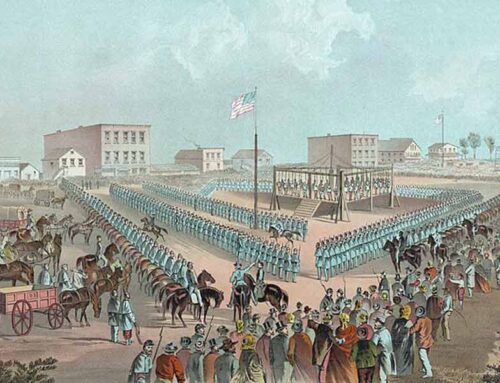

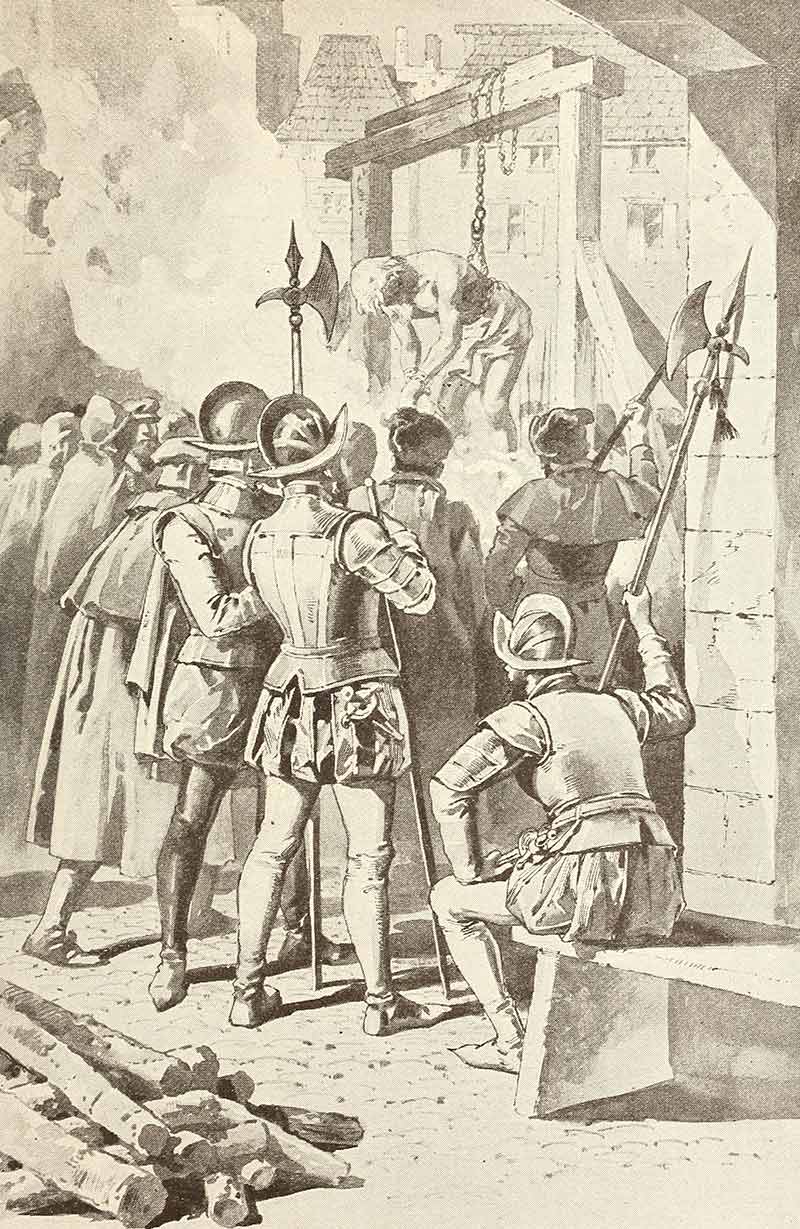

Sir John Oldcastle was then brought to London’s St. Giles in the Field, and there on December 15, 1417, was suspended by chains over a slow fire and cruelly burned to death. Of his legacy in the faith renowned church chronicler, John Foxe, wrote:

“Thus resteth this valiant Christian knight, Sir John Oldcastle, under the altar of God, which is Jesus Christ, among that godly company, who, in the kingdom of patience, suffered great tribulation with the death of their bodies, for His faithful word and testimony.”

The martyrdom of John Oldcastle

Image Credits: 1 William Shakespeare (wikipedia.org) 2 Shakespeare’s characters (wikipedia.org) 3 The Thanksgiving Service on the Field of Agincourt, Leighton (wikipedia.org) 4 Falstaff (wikipedia.org) 5 Cooling Castle (wikipedia.org) 6 John Wycliffe (wikipedia.org) 7 Reformation Wall, Geneva (wikipedia.org) 8 Tower of London (wikipedia.org) 9 The White Tower (wikipedia.org) 10 King Henry V (wikipedia.org) 11 Martyrdom of John Oldcastle (wikipedia.org)