“Give instruction to a wise man, and he will be still wiser; teach a righteous man, and he will increase in learning.”

—Proverbs 9:9

Henry Knox and

the Guns of Fort Ticonderoga,

January 24, 1776

![]() t is not hyperbole to say that America has produced some of the most singularly audacious individuals in the history of the world. And they, in turn, were essential in creating America, the greatest experiment in liberty ever attempted, with the greatest passion for justice ever embodied in a people.

t is not hyperbole to say that America has produced some of the most singularly audacious individuals in the history of the world. And they, in turn, were essential in creating America, the greatest experiment in liberty ever attempted, with the greatest passion for justice ever embodied in a people.

Without these rugged individuals with their inexhaustible faith, and self-made genius, the Declaration of Independence and its world-altering impact would have remained a political manifesto with no collective will behind it. By their blood and love, these brave founding Americans ensured the future of our nation, and in the process defined what it meant to embody the American spirit.

One such American was a common Boston bookseller, Mr. Henry Knox. This is the story of only one of many pivotal contributions he made to the American cause, achieved 250 years ago this week.

Henry Knox (1750-1806)

After the climactic clashes in April 1775 between American militia and the British Army at Lexington and Concord, tensions were high. A stalemate ensued—both politically and militarily. The Battle of Bunker Hill followed but did little to change the landscape other than to cement the gravity of the situation, and underscore that this was now a fight for independence, not just a colonial misunderstanding. General Washington immediately laid siege to the British inside of Boston in April 1775, with a Continental Army comprised of a most irregular and ill-supplied collection of volunteers from the various colonies.

The besieging colonists had plenty of muskets and did not lack enthusiasm, but they were without heavy artillery like cannons, which were essential for bombarding the in-town fortifications, or dominating the high ground. Most of their powder and shot were homemade, and they had no foundries to produce big guns domestically. The British, on the other hand, had naval support in Boston Harbor and professional artillery, giving them the edge in the prolonged standoff that resulted. The siege of Boston continued thus for nine months, into January of 1776, with every council of war that Washington held ending in agreement that an all-out attack would be disastrous.

During this time, Washington put increasing trust in two young, self-made New Englanders: Nathanael Greene, a Rhode Island blacksmith, and his close friend and bookseller, Henry Knox.

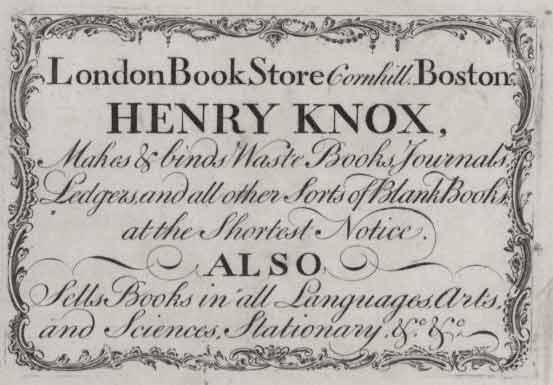

Advertisement for Henry Knox’s London Book Store in Boston

Six feet tall and weighing about 250 pounds, Henry Knox was hard not to notice. He was gregarious, jovial, quick of mind, highly energetic, and all of twenty-five years old. Like his friend, General Nathanael Greene, he was a voracious reader and almost entirely self-educated. After a hard upbringing, Knox had, at the age of twenty-one, founded the London Book Store in Boston, fostering it into a “fashionable morning lounge,” which attracted the city’s intelligentsia, including notables such as John Adams. When Boston came under siege, Knox’s bookshop was looted by the British, and Knox fled with his wife Lucy to Washington’s army.

By the end of 1775, Knox was enjoying the distinguished rank of colonel in Washington’s newly-formed artillery regiment. Such a regiment did not, in fact, actually exist as there was no artillery for the patriots to employ. But by appointing the ingenious Knox as its head, Washington doubtless hoped for a remedy to this crippling disadvantage.

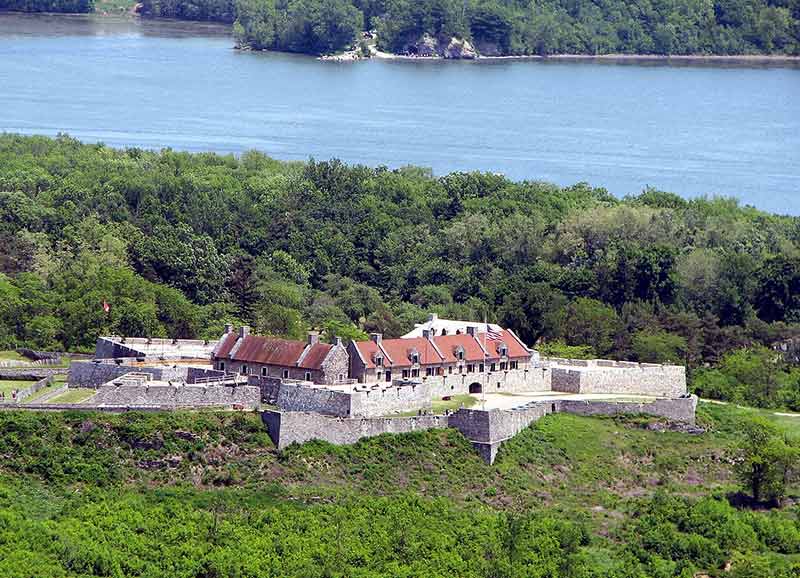

Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain

Knox’s bright mind soon supplied it. Fort Ticonderoga, on Lake Champlain in northern New York, had been captured by the patriots in early 1775, but the fort and its captured artillery were soon after abandoned. Knox told Washington he was confident the precious guns could be retrieved and hauled overland and used to besiege Boston, despite the inclement weather and grueling distance presented. Washington agreed to his plan at once, and put the young officer in charge of the expedition. Knox left to accomplish his proposed feat on November 16, 1775, accompanied by only a few aides and his nineteen-year-old brother, William, possessing the authority to spend as much as $1,000 on logistics.

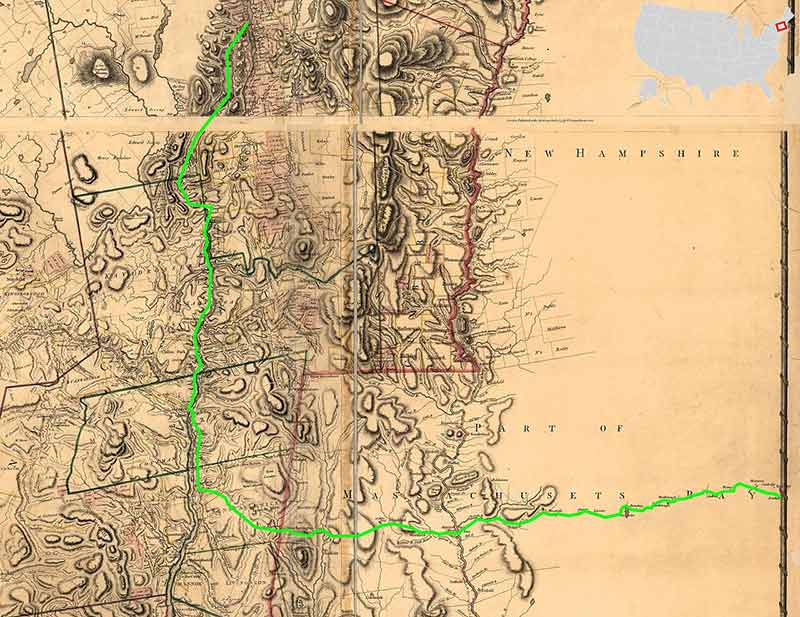

A map showing what is now commemorated as the Henry Knox Trail, outlining the majority of his route

They went to New York City first, and there Henry Knox put his autodidactic brilliance to work in arranging for the materials and supplies needed, and then headed to Fort Ticonderoga itself, making the rigorous progress of forty miles a day at times.

The first snow of the year fell on November 21, and in the days to follow it was obvious winter had come to stay, with winds as bitter as January and still more snow. The distress within besieged Boston grew extreme, as did the plight of the patriot besiegers: desertions surged, smallpox killed hundreds, and all of Washington’s efforts and those of his senior officers were concentrated on trying to hold the army together. If Knox failed to accomplish this mission—an undertaking so enormous, so fraught with certain difficulties, that many thought it impossible—then devastation appeared to be the only possible outcome for the American cause.

On December 5, 1775 Colonel Knox arrived at the fort and took inventory of the abandoned artillery pieces. The guns Knox had come for were mostly French mortars, some 12- and 18-pound cannon (that is, guns that fired cannonballs of 12 and 18 pounds, respectively), and one giant brass 24-pounder. Not all were in usable condition. After looking them over, Knox selected 58 mortars and cannon. Three of the mortars weighed a ton each and the 24-pound cannon, more than 5,000 pounds. The whole lot was believed to weigh not less than 120,000 pounds.

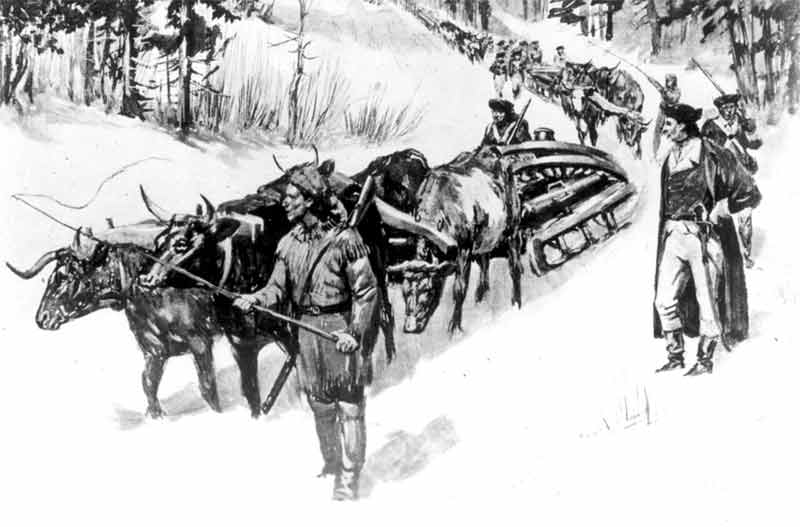

Knox and his crew employing oxen to pull the cannons through the snowy mountains

The plan was to transport the guns by boat down Lake George, which was not yet completely frozen over. At the lake’s southern end would begin the long haul overland, south as far as Albany before turning east toward Boston across the Berkshire Mountains. The distance to be covered was nearly 300 miles. Knox planned to drag the guns on giant sleds and was counting on snow. But thus far only a light dusting covered the ground. With the help of local soldiers and hired men, he set immediately to work. Just moving the guns from the fort to the boat landing proved a tremendous task. The passage down Lake George alone, not quite forty miles, took eight days.

The Champlain Valley

Three boats carrying the cargo of fifty-eight guns set sail on December 9. Judging from Knox’s hurried, all-but-illegible diary entries, their first hour on the lake appears to have been the only hour of the entire trek that did not bring “the utmost difficulty.” One of the boats, a scow, struck a rock and sank, though close enough to shore to be bailed out, patched up, and set afloat again. Knox recorded days of heavy rowing against unrelenting headwinds—four hours of “rowing exceeding hard” one day, six hours of “excessive hard rowing” on another. At other times, they had to cut through ice to make a path for the boats.

On his journey up to Ticonderoga, Knox had arranged for heavy sleds or sledges to be rounded up or built, forty-two in all, and to be on hand at the southern end of Lake George, about thirty-five miles south of Ticonderoga. Now ashore, with the sleds and eighty yoke of oxen, he was ready to push on. In a letter to his wife, Lucy Knox, he now assured her the most difficult part was over, and speculated, “We shall cut no small figure through the country with our cannon.” But then there came no snow. Instead, a “cruel thaw” set in, halting progress for several days. The route south to Albany required four crossings of the Hudson. With the weather being so mild, the ice on the river was too thin, and the heavy caravan could only stand idly by at Fort George and wait for a change. When the change came, it was a blizzard. Three feet of snow fell, beginning Christmas Day. Determined to go ahead on his own to Albany in order to prepare the way, Knox nearly froze to death struggling through the snow on foot, until finding horses and a sleigh to take him the rest of the route.

One of many markers along Knox’s route (this one in West Ghent, NY), commemorating the incredible feat

Eventually, his “precious convoy” pushed off from Fort George. “Our cavalcade was quite imposing,” remembered young John Becker, who at age twelve had accompanied his father, one of the drivers on the expedition. They proceeded laboriously in the heavy snow, passing through the village of Saratoga, then on to Albany, where Knox had been busy cutting holes in the frozen Hudson in order to strengthen the ice—the idea was that water coming up through the holes would spread over the surface of the ice and freeze, thus gradually thickening the ice. He had read of it in a book.

The Hudson River, frozen over

For several hours it appeared that the theory had worked perfectly. Indeed, nearly a dozen sleds crossed without mishap. But then, suddenly, one of the largest cannons, an 18-pounder, broke through and sank, leaving a hole in the ice fourteen feet in diameter. Undaunted, Knox at once set about retrieving the cannon from the bottom of the river, losing a full day in the effort, but at last succeeding, as he wrote, “owing to the assistance of the good people of Albany.”

On January 9, as the expedition pushed on from the eastern shore of the Hudson, they still had more than a hundred miles to go. Snow in the Berkshires lay thick, exactly as needed, but the mountains—steep and dissected by deep, narrow valleys—posed a challenge as formidable as any. Knox, with no prior experience in such terrain, wrote of climbing peaks “from which we might almost have seen all the kingdoms of the earth. . . . It appeared to me almost a miracle that people with heavy loads should be able to get up and down such hills.” To slow the descent of the laden sleds down slopes as steep as a roof, check lines were anchored to trees. Brush and drag chains were shoved beneath the runners. When some of his teamsters, fearful of the risks, refused to go any further, Knox spent three hours arguing and pleading until finally they agreed to head on.

News of the advancing procession raced ahead of them and, as Knox had imagined, people began turning out along the route to see for themselves the procession of the guns from Ticonderoga. “We found that very few, even among the oldest inhabitants, had ever seen a cannon,” twelve-year-old John Becker later recalled. “We were the great gainers by this curiosity, for while they were employed in remarking upon our guns, we were, with equal pleasure, discussing the qualities of their cider and whiskey. These were generously brought out in great profusion.”

At Springfield, to quicken the pace, Knox changed from oxen to horses pulling the sleighs, and on the final leg of the journey the number of onlookers grew by the day. The final halt came at last about twenty miles west of Boston at Framingham where the guns were unloaded, awaiting orders. Knox, in the meantime, sped on to Cambridge to report to Washington—by God’s grace he had done it. His “noble train” had arrived intact. Not a gun had been lost. The siege of Boston was broken shortly thereafter, the juggernaut of British occupation fleeing to safety in Canada.

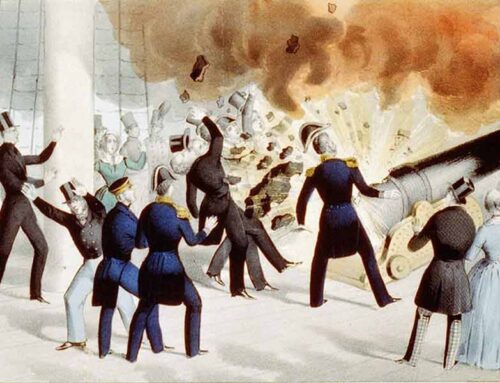

The British evacuating Boston—the event is celebrated locally as Evacuation Day to this day

Hundreds of men had taken part in the endeavor of procuring the guns from Fort Ticonderoga, and their labors and resilience had been exceptional. But it was the daring and determination of Henry Knox that had counted above all. In the words of historian David McCullough: “The twenty-five-year-old Boston bookseller had proven himself a leader of remarkable ability, a man not only of enterprising ideas, but with the staying power to carry them out.”

He would retain his position as chief of artillery under General Washington—this time with the fire-power to back it. Knox would go on to fight through the entirety of the War for Independence and, after independence was secure, would go on to serve as President Washington’s Secretary of War during the former’s first term. But this was all in the future—what cemented Knox as an American hero was his daring resourcefulness in the early days of the fight, before our independence had even been proclaimed. Such risks and such devotion are why, by God’s great lovingkindness, our dear country came into being at all. It is unsurprising that a man of books had the vision to perceive what monumental times he was in, and lend his hand accordingly, as he wrote his wife, “We are fighting for our country, for posterity perhaps. On the success of this campaign the happiness or misery of millions may depend.”

Knox and his crew arrive in camp, having successfully brought all the cannon they had set out to retrieve

Image Credits: 1 Henry Knox (wikipedia.org) 2 London Book Store (wikipedia.org) 3 Fort Ticonderoga (wikipedia.org) 4 Route (wikipedia.org) 5 Trekking through the mountains (wikipedia.org) 6 Champlain Valley (wikipedia.org) 7 Henry Knox Trail marker (wikipedia.org) 8 Hudson River frozen (wikipedia.org) 9 The Evacuation of Boston (wikipedia.org) 10 Cannon arrive in camp (wikipedia.org)