Tragedy Aboard the USS Princeton: President Tyler’s Cabinet Decimated, 1844

“Seeing his days are determined, the number of his months are with thee, Thou hast appointed his bounds that he cannot pass.” —Job 14:5

Tragedy Aboard the USS Princeton: President Tyler’s Cabinet Decimated, February 28, 1844

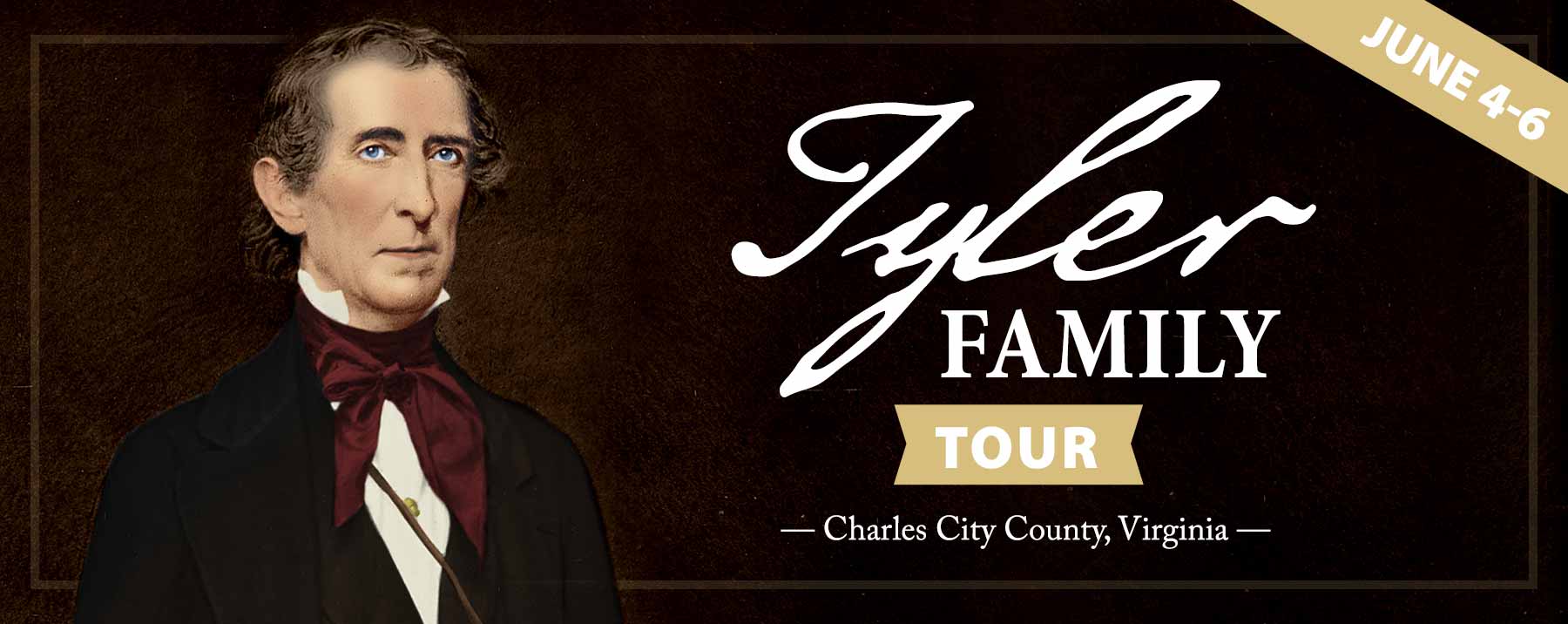

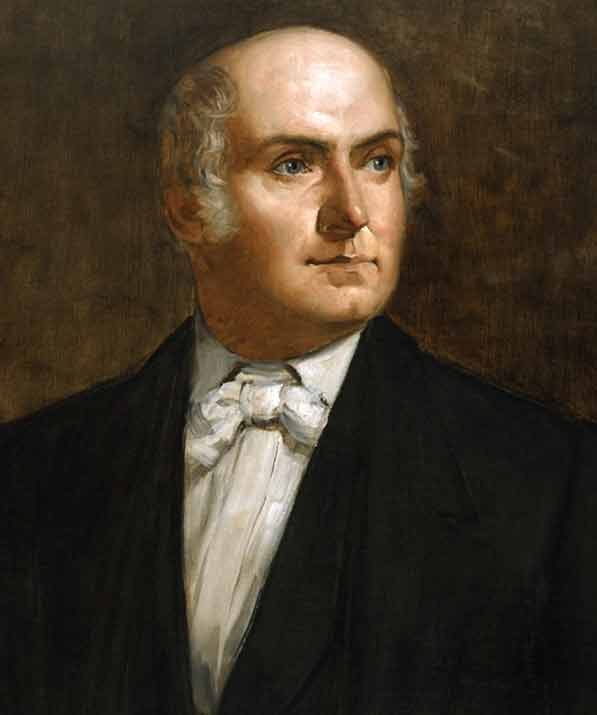

![]() he single deadliest tragedy to claim multiple top government officials happened on February 28, 1844, during a Potomac River pleasure cruise. The U.S. was in a peacetime lull, with no major conflicts since the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War still two years in the future. The “fabulous forties”, as the decade would later be known, was well under way. President Tyler was enjoying a successful—if rather turbulent—administration, having become the first Vice President to succeed to the office after the death of the incumbent, that being the short-serving William Henry Harrison.

he single deadliest tragedy to claim multiple top government officials happened on February 28, 1844, during a Potomac River pleasure cruise. The U.S. was in a peacetime lull, with no major conflicts since the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War still two years in the future. The “fabulous forties”, as the decade would later be known, was well under way. President Tyler was enjoying a successful—if rather turbulent—administration, having become the first Vice President to succeed to the office after the death of the incumbent, that being the short-serving William Henry Harrison.

John Tyler (1790-1862), circa 1842

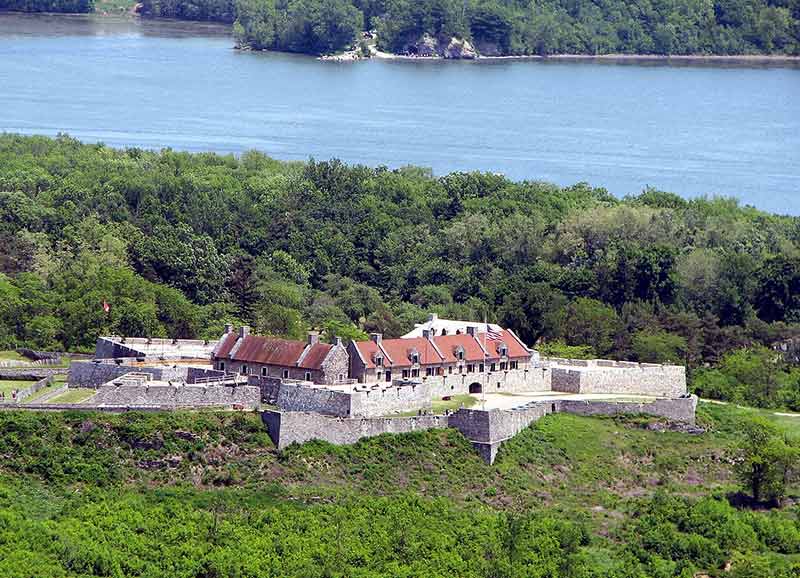

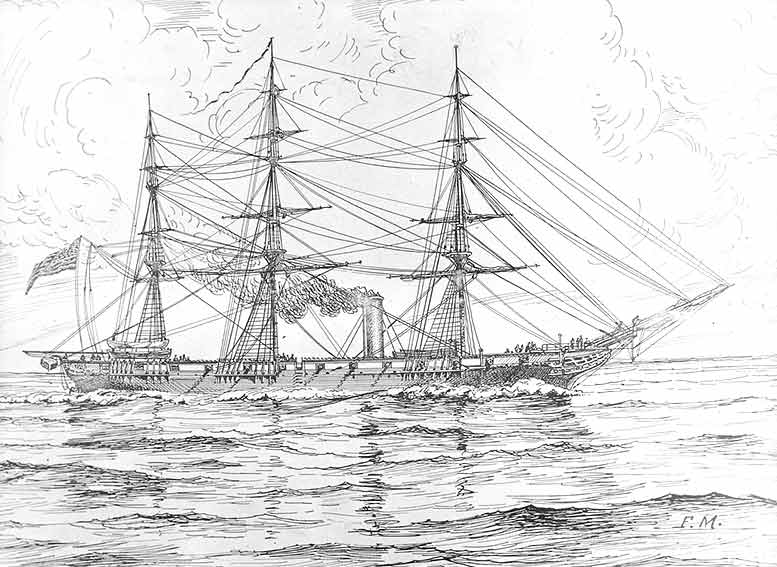

Roughly three years into his term, President Tyler agreed to a diplomatic cruise on the new, state-of-the-art warship, the USS Princeton. She was the first of her kind with screw propellers enabling her to break through ice, and an engine mounted below the waterline to protect from gunfire. An innovative wonder and pride of the United States Navy, the ship also boasted an impressive 12 inch muzzleloader, named Peacemaker. The Princeton’s Captain, Robert F. Stockton, had designed the gun himself and had mounted it with only a limited amount of testing for its efficacy.

On February 28, USS Princeton departed Alexandria, Virginia with Tyler, members of his cabinet, former First Lady Dolley Madison, over half a dozen Senators and about 400 other prestigious guests. Crowds thronged the shoreline to watch her progress, and her guns were shot off in salute, repeatedly. Along the way Captain Stockton decided to fire his own invention, Peacemaker, at the behest of his impressed guests.

The USS Princeton

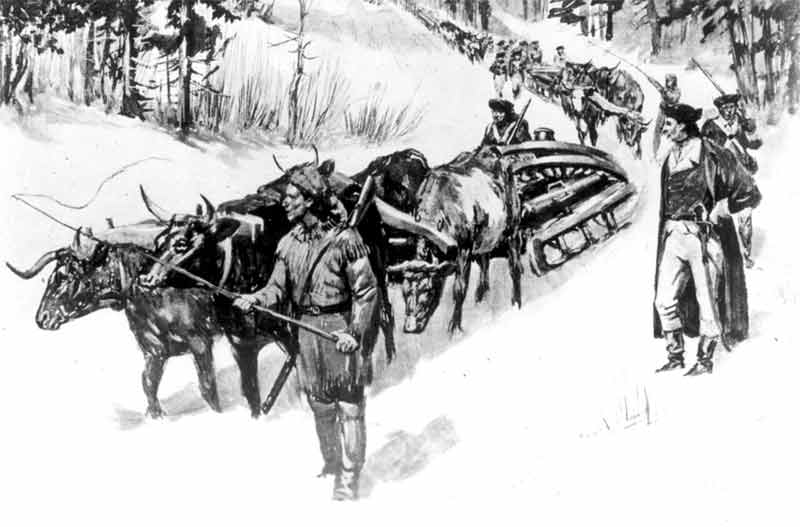

Peacemaker was fired successfully three times in total on the trip downriver. The many guests then retired below deck for lunch and refreshments. Toasts were raised to the Navy. Stories were swapped by the many distinguished guests. So pleasant a time was being had by many that Secretary of the Navy Gilmer’s urgings to go above deck and view Peacemaker’s final salute as they passed Mount Vernon was met with only tepid interest. Most of the ladies declined to leave their seats and only President Tyler’s agreement to go above convinced others to leave their refreshments and rejoin the crew on the gun deck.

However, in an incredible instance of Providence—touchingly outworked in the form of familial love—Tyler felt compelled to linger below a little while longer, until his son-in-law finished his rendition of a sea shanty. The delay most likely saved President Tyler his life. He was halfway up the ladder when above deck, Captain Stockton pulled Peacemaker’s firing lanyard and the big gun burst. Its left side failed completely, spewing chunks of hot metal all across the deck and into the assembled onlookers.

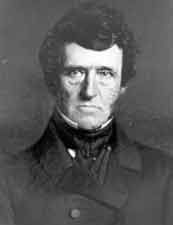

Captain Robert Field Stockton (1795-1866)

A contemporary Currier & Ives illustration of the Peacemaker’s explosion aboard the USS Princeton

Five men were instantly killed: Secretary of State Abel Upshur; Secretary of the Navy Thomas Walker Gilmer; Captain Beverley Kennon; the Navy’s Chief of Construction, Virgil Maxcy, a Maryland attorney and federal officeholder; and David Gardiner, a New York lawyer, Senator and the father of Tyler’s 23-year-old fiancée, Julia. A sixth man, Armistead—President Tyler’s valet and close friend—died only a few moments later.

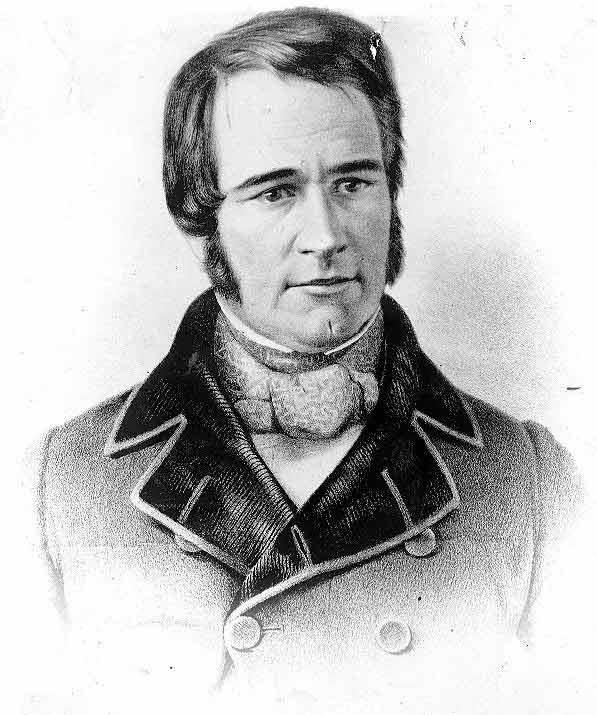

Secretary of State, Abel Parker Upshur (1790-1844)

Secretary of the Navy, Thomas Walker Gilmer (1802-1844)

This dreadful death toll made the explosion stand out as the Navy’s worst disaster during peacetime up to that point, killing more high-level figures at once than any other incident in American history. Around twenty others were injured to varying degrees, including Captain Stockton himself. The entire ship trembled from the deafening blast, a dense cloud of white smoke smothered everything, quickly roiling down the stairs and choking the luncheon party, as the crew’s screams for a surgeon rose amidst the pandemonium. It was almost impossible to see or breathe as the ship’s occupants rushed above decks to ascertain the damage. The scene was gruesome in the extreme. According to the editor of the Boston Times—himself an eyewitness—when the smoke had cleared, dead bodies with detached arms and legs could be seen littering the deck. Unconscious guests with open head wounds lay near the destroyed gun. Some of the wounded were struck deaf by the explosion, their eardrums ruptured. Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri was blown flat on his back and suffered a concussion, while a woman who had been holding his arm was thrown into the rigging, although amazingly, she was unhurt.

It is said that when President Tyler saw the bodies of his cabinet officers, Upshur and Gilmer, and that of his valet Armistead, he wept. Lovely, plucky and very young, Julia Gardiner rushed above deck, saw the mangled remains of her father, and promptly fainted into the arms of President Tyler. Another vessel came alongside the devastated Princeton and took aboard the wounded and the two hundred shaken ladies: President Tyler carried Julia Gardiner over the gangway himself before returning to lend whatever help he could. One woman who did not leave Princeton’s decks in the immediate aftermath was the grand dame of Washington, former First Lady, Dolley Madison. At seventy-seven years of age, she stayed behind and tended to the wounded with her own hands, pale but staunch in her nauseating work.

Dolley Madison (1768-1849), photographed in 1846

In the aftermath, rather than ascribe responsibility for the explosion to individuals, Tyler wrote to Congress the next day that the disaster “must be set down as one of the casualties which, to a greater or lesser degree, attend upon every service, and which are invariably incident to the temporal affairs of mankind.”

The public reaction to the tragedy aboard the Princeton was, of course, one of profound shock and national mourning. The National Intelligencer noted soberly:

“Never in the mysterious ordinance of God has a day on earth been marked in its progress by such startling and astounding contrasts—opening and advancing with hilarity and joy, mutual congratulation and patriotic pride, and closing in scenes of death, and disaster, of lamentation and unutterable woe.”

The ship’s bell from the USS Princeton

The unease the incident sparked was amplified by the near-miss of losing President John Tyler himself, along with the contextual complication of Tyler having no clear successor. The situation was such that by February of 1844, there was still no clearly defined succession in regards to the Presidency in the event of a President’s death.

Back in 1841, John Tyler had been William Henry Harrison’s Vice President, and upon Harrison’s untimely death, Tyler had rushed from his home in Williamsburg, Virginia to Washington, D.C. in order to have himself installed as Harrison’s successor—fearing with good reason that Senate majority leader, Henry Clay, might make a claim for the same. Tyler had been successful in his daring and had served out the rest of the ill-fatted Harrison’s term as his own, although he was referred to ever after as “His Accidency.” Thus Tyler had set the precedent for succession under the Constitution’s “accidental presidency” clause, but he had done so without a replacement Vice President of his own.

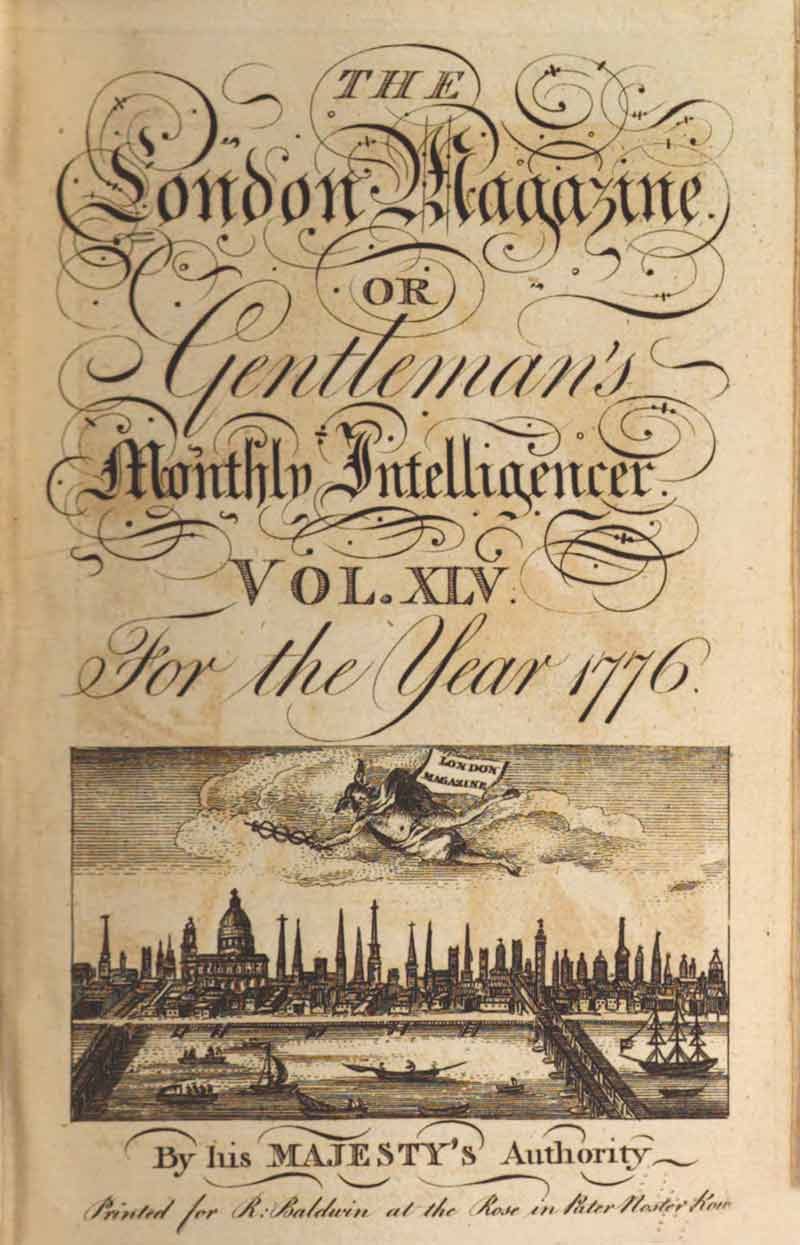

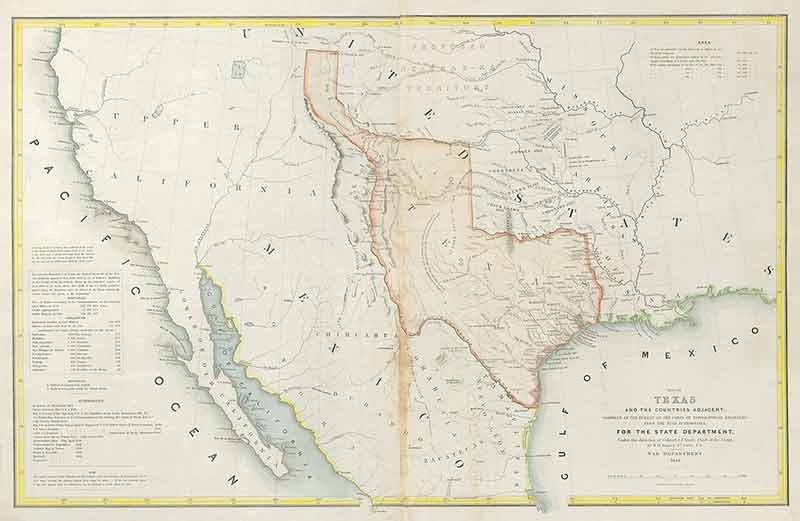

An 1844 map titled “Map of Texas and the Countries Adjacent”

If Tyler had died in this freak accident, the rules for Presidential succession might look very different today, and matters of great consequence to our nation never have been achieved. One such accomplishment that Tyler achieved was laying the groundwork for bringing the great Republic of Texas into the Union. This goal became the great ambition of Tyler’s last year in office, one that he was energetically aided in by his young wife, the pretty Miss Julia Gardiner who had lost her father aboard the Princeton. After Tyler had signed the necessary papers to bring Texas in, he gave Julia the golden pen he had used, and she proudly wore it from a necklace about her neck. It was said this joint goal of theirs cost him re-election, but by that time Tyler had become known as the President without a party, one of the only men in Washington principled enough to vote in line with his conscience and not affiliation.

Julia Gardiner Tyler (1820-1889) in 1844, the year of both the Princeton incident as well as her marriage to John Tyler

In the same vein, John Tyler would become the only United States President to die a citizen of another country—he had, along with his native state of Virginia, seceded in 1861 from the Union he had once sought to enlarge, and was serving at the time of his death as a Representative of the Confederate States of America.

Step into Virginia’s living history on this immersive journey through four generations of the Tyler family. From the founding era and the constitutional defense of the young Republic, through the trials of the War Between the States and into the modern age of historic preservation, Dr. Bill Potter will lead you through ancestral homes and gravesites that anchor each generation’s story. Along the way, we examine themes of multigenerational vision, public service, and preparing one’s children for lives of purpose. We will reflect on Jamestown’s centennial commemorations and attend the annual reenactment at Fort Pocahontas, considering the war’s impact on this important Virginia family and the enduring importance of historical memory. Learn More & Register >>

Image Credits: 1 John Tyler (wikipedia.org) 2 USS Princeton (wikipedia.org) 3 Captain Stockton (wikipedia.org) 4 Currier & Ives Illustration (wikipedia.org) 5 Abel Upshur (wikipedia.org) 6 Thomas Gilmer (wikipedia.org) 7 Dolley Madison (wikipedia.org) 8 Ship’s Bell (wikipedia.org) 9 1844 Texas Map (wikipedia.org) 10 Julia Tyler (wikipedia.org)