“But my servant Caleb, because he has a different spirit and has followed me fully, I will bring into the land into which he went, and his descendants shall possess it.” —Numbers 14:24

John Champe and the Plot to Kidnap

the American Judas, October 13, 1780

n October 13, in the year 1780, General Washington invited one of his cavalry commanders, Major Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, to his headquarters to discuss “a particular piece of business.” At this secretive meeting, Washington broached a topic that had rankled him greatly: the recent treason of Benedict Arnold and how to repay it.

n October 13, in the year 1780, General Washington invited one of his cavalry commanders, Major Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, to his headquarters to discuss “a particular piece of business.” At this secretive meeting, Washington broached a topic that had rankled him greatly: the recent treason of Benedict Arnold and how to repay it.

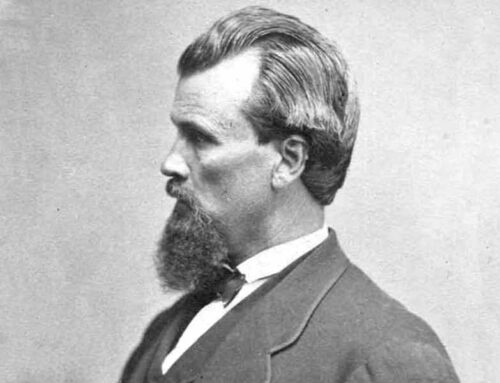

Benedict Arnold (1741-1801)

Before his name became synonymous in America with treachery, Benedict Arnold had been a great patriot hero. He was the twice-wounded victor of Saratoga, one of Washington’s most reliable officers, and the one he entrusted with the defense of West Point. A self-pitying descent into vainglorious ambition, disgruntlement with the leadership of Congress, and the honeyed drip of his Tory wife’s persuasions to join the Royalist cause came to a despicable culmination when Arnold contacted the British general, Sir Henry Clinton, and offered to sell his post at West Point.

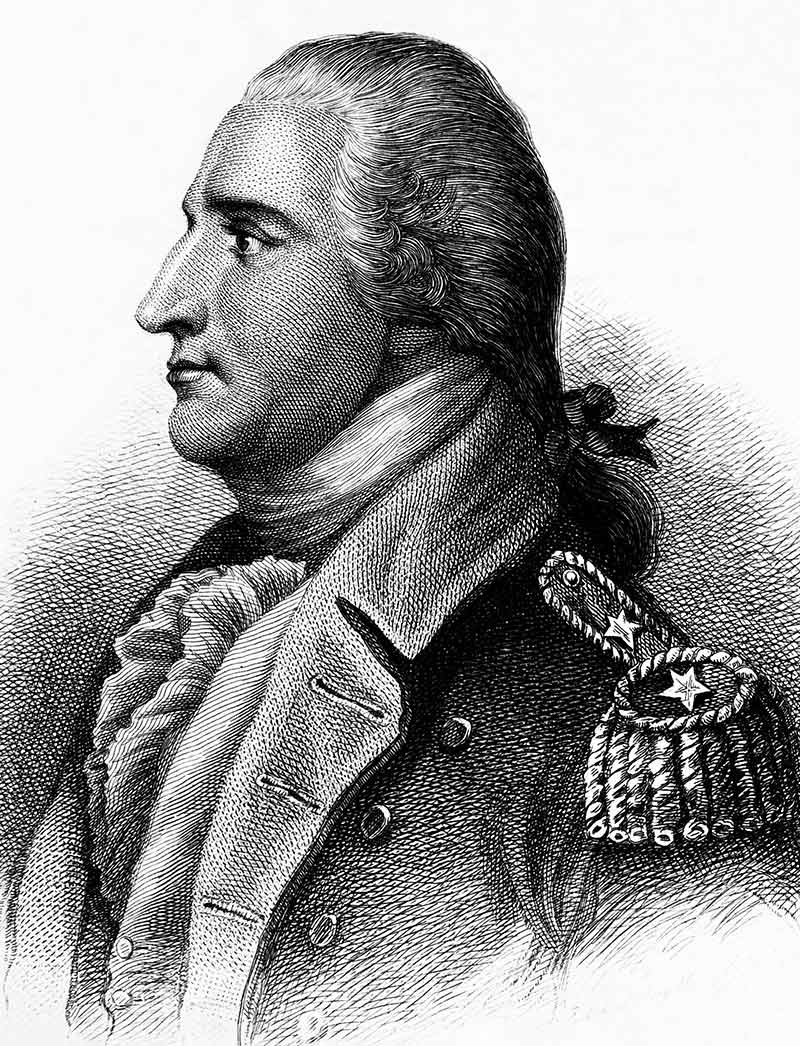

Sir Henry Clinton (1730-1795)

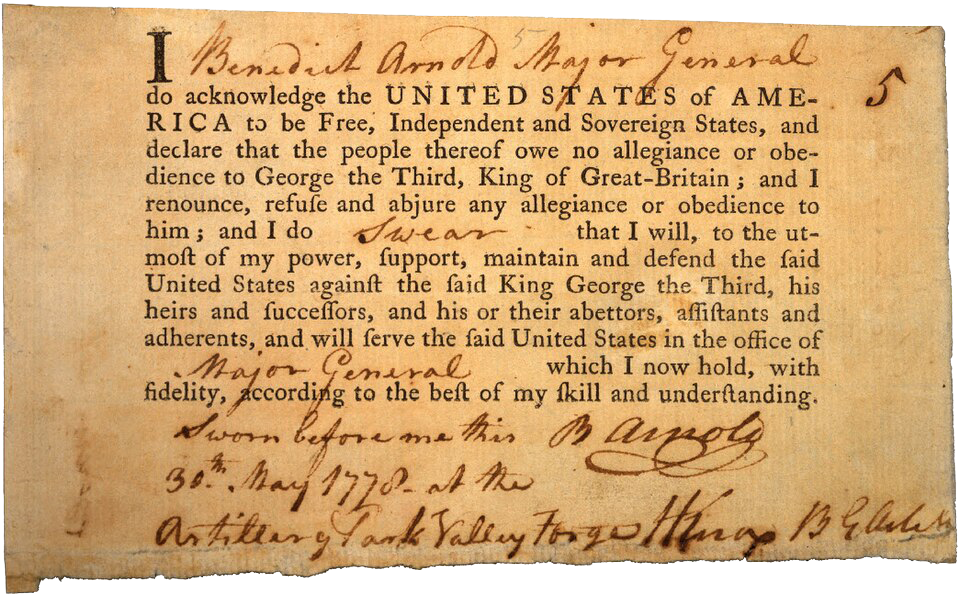

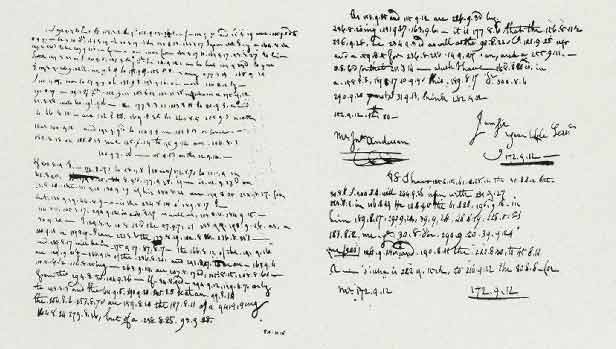

Benedict Arnold’s oath of allegiance to the United States of America, signed at Valley Forge, May 30, 1778

Benedict Arnold’s price for this treachery was £20,000 (approximately $3.5 million in today’s value) in return for the fortification of West Point and all its garrison. Additionally, Arnold sought a commission in the British Army and a pension. When Washington and his staff paid Arnold an impromptu visit at West Point during these duplicitous negotiations, Arnold contacted his British agent again and—not being satisfied with the extent of his grubby perfidy—told the British to increase the sum because he was now in a position to hand over Washington himself to the British.

The home occupied by Benedict Arnold while commander of West Point

This plot was foiled by sheer Providence, involving the stopping of Arnold’s British contact—a Major John Andre—by a squad of drunken Continental soldiers who originally only wished to rob the man, but who then discovered the damning maps and papers detailing the plot. These were forwarded with haste to Washington’s staff officers who set in motion a well-executed lockdown of West Point. But they did not act quickly enough to catch Arnold, who fled out of his literal back door and caught a boat headed up river. His charming wife—the remarkably shrewd Peggy Shippen Arnold—served as a decoy for his escape by pretending to descend into a fit of feminine hysterics and thus split the energies of Washington’s staff who sought to comfort her.

Peggy Shippen Arnold (1760-1804), wife of Benedict Arnold, with their daughter

The escape pf Benedict Arnold from West Point

Since the incident at West Point, Benedict Arnold had set himself up in British-occupied New York. He received the commission he craved and some of the stated wages for his betrayal. He was a despised character amongst the British, however, as no one likes a turncoat. Not being trusted by them with the command he sought after, he set himself up as “Spymaster General”, hoping to gain British approbation by ruthlessly ferreting out every brave patriot citizen informant who worked in Washington’s spy rings.

One of Benedict Arnold’s coded communications with the British while he was negotiating his attempt to surrender West Point. Lines of text written by his wife, Peggy, are interspersed with coded text (originally written in invisible ink) written by Arnold.

Enraged by Arnold’s past treachery and current persecution of these informants, Washington called Major Henry Lee to his tent on October 13, 1780 and proposed a laughably daring plot: they would kidnap Arnold and bring him back so that justice might be served. Could Lee find a man among his cavalry willing to embark on such a mission?

Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee III (1756-1818)

It took Lee a week to find two volunteers “to undertake the accomplishment of your Excellency’s wishes.” Interestingly, Lee omitted to mention to these volunteers that they were acting on Washington’s specific orders since, if they failed, the commander-in-chief’s name could not be linked to such an unorthodox mission. The first man was a sergeant in Lee’s regiment named John Champe. A tall Virginian in his early twenties, his taciturn nature and “total absence of cheerfulness” masked a “remarkable intelligence”, according to Lee.

His task would be to enter New York, somehow capture Arnold, and bundle him down to a waiting boat for removal to Patriot-held New Jersey. Modestly desirous of an officer’s commission, all Champe asked for in reward for his dangerous services was a promotion. The other volunteer, whose name was never revealed, would be Champe’s contact man in Newark, New Jersey, and Lee promised him “one hundred guineas, five hundred acres of land, and three negroes.”

Washington was most pleased at Champe’s public-spiritedness. He admitted himself reluctant to cast around for officers to undertake the business, which even he regarded as being a shade dishonorable. After inquiring into Champe’s details, in the strictest of confidences, Washington authorized the operation and approved the rewards Lee had arranged with “the conductors of this interesting business.” He made one stipulation: Arnold was to be brought in alive. If he were killed during the mission, the British would be quick to spin it as “ruffians being hired to assassinate him,” whereas Washington’s aim was “to make a public example of him.”

After these arrangements had been made, Lee summoned Sergeant Champe to his quarters and ordered him to desert to the enemy immediately. To ensure complete authenticity, Lee added that no help could be given to Champe during his flight; he would have to find his way to the British lines as if he were a real turncoat. The most Lee could offer was to delay pursuit for as long as he could if Champe’s absence was noted before the next morning.

With that, Champe collected his belongings (including the regiment’s orderly book, for added authenticity) and rode his horse out of camp at about 11 o’clock that night. He was given three guineas to cover his immediate expenses (Washington refused him any more, saying it would ring too many alarm bells) and the names of two known friendlies in New York.

No one stopped Champe’s leaving, but just half a mile out of camp, at a crossroads, a mounted Patriot patrol returning from duty issued a challenge. Champe kept silent, pulled up his hood, plunged his spurs into his steed’s flanks, and galloped past them. The patrol gave chase but their horses were tired and they soon quit. Unfortunately, the patrol belonged to Lee’s own regiment, and half an hour later a certain Captain Carnes briskly woke up Major Lee to tell him of the incident. Lee understood instantly it was Champe that they had seen and played dumb, forcing the captain to repeat his entire story, questioning tiny details, dismissing Captain Carnes’ belief that the mysterious rider, judging by his riding style, was a cavalryman and suggesting instead he was “a countryman” in a hurry.

Lee could see Captain Carnes wasn’t convinced, and finally was forced to direct him to muster every man and horse and see if any were missing. That would waste yet another hour, at least, Lee hoped. Sooner than he expected, Captain Carnes returned and declared that one, a Sergeant Champe, was gone. It had come to the point where to continue piddling would invite suspicion, and Lee called out the regiment to give pursuit, as would be expected in the context of a desertion.

A pursuit party was selected and Lee chose a young cornet named Middleton, whom he knew lacked Captain Carnes’ experience and rigor, to lead it. Lee thought him to be of a gentle enough disposition that he would not kill Champe outright were he to capture him. In his quarters with Middleton, Lee managed to waste ten minutes going over in tedious detail exactly which route he should take, which equipment he might need, and how many men he should bring. Finally, after waiting precious minutes for Lee to sign his orders and reiterate how Champe should be treated humanely, an impatient Middleton was allowed to go.

Champe, thanks to Lee’s intervention, had gained an hour’s head start, but by that point, it unexpectedly began to rain: not hard enough to prevent pursuit, but sufficient to leave tracks on the muddy roads. Lee’s men were dragoons, and none in the army knew better than they how to follow hoof-prints. Worse yet, the regiment had one farrier who used a single, peculiar pattern of horseshoe, which made their tracts distinct. Unlike his pursuers, Champe could not afford to gallop through the countryside. Aside from the risk of laming his horse, the place swarmed with colonial militiamen who might set off a hue and cry at the sight of a lone, be-cloaked horseman running at full pelt so late at night.

Therefore, by dawn, Champe was still several miles north of Bergen, New Jersey on a wide and open plain where he could be easily spotted. Behind him he could hear the faint clatter of hooves, and knew his pursuers were closing. Looking behind him, Champe was horrified to see several horsemen pausing at the crest of a hill half a mile away and signaling to their comrades that the quarry was near. Champe gave spur to his horse and he made for the bridge traversing the Hackensack River. Most of the pursuers, including their leader Middleton, were local men and knew the terrain far better than the man they pursued. Middleton split his forces in two, so as to trap Champe in a pincer at the bottom of the hill near the river’s crossing. Caught between two forces, Champe would be forced to surrender.

And yet, Middleton miscalculated Champe’s brazen daring. Seeing his intended path was blocked and the original plan to defect to Paulis Hook (a British fortress on the Jersey shore) was impossible, Champe instead plunged straight ahead into the town of Bergen itself. He tore down one paved street after another before taking the road leading to the Hudson River, not the one heading to Paulus Hook.

Seeing his miscalculation, Middleton gave chase. There were two British ships anchored a mile ahead of Champe on the Hudson, and he made for them. Behind him, also a mile away, were the pursuing cavalrymen. There was nothing for it but to lighten the horse’s load and make a break for it. After shrugging off his cloak and tossing away his scabbard, Champe reached the shore in quick time but lost valuable minutes trying to attract the crews’ attention by dismounting and waving his arms. By the time the crews noticed him, Middleton had closed the distance and was just two hundred yards away.

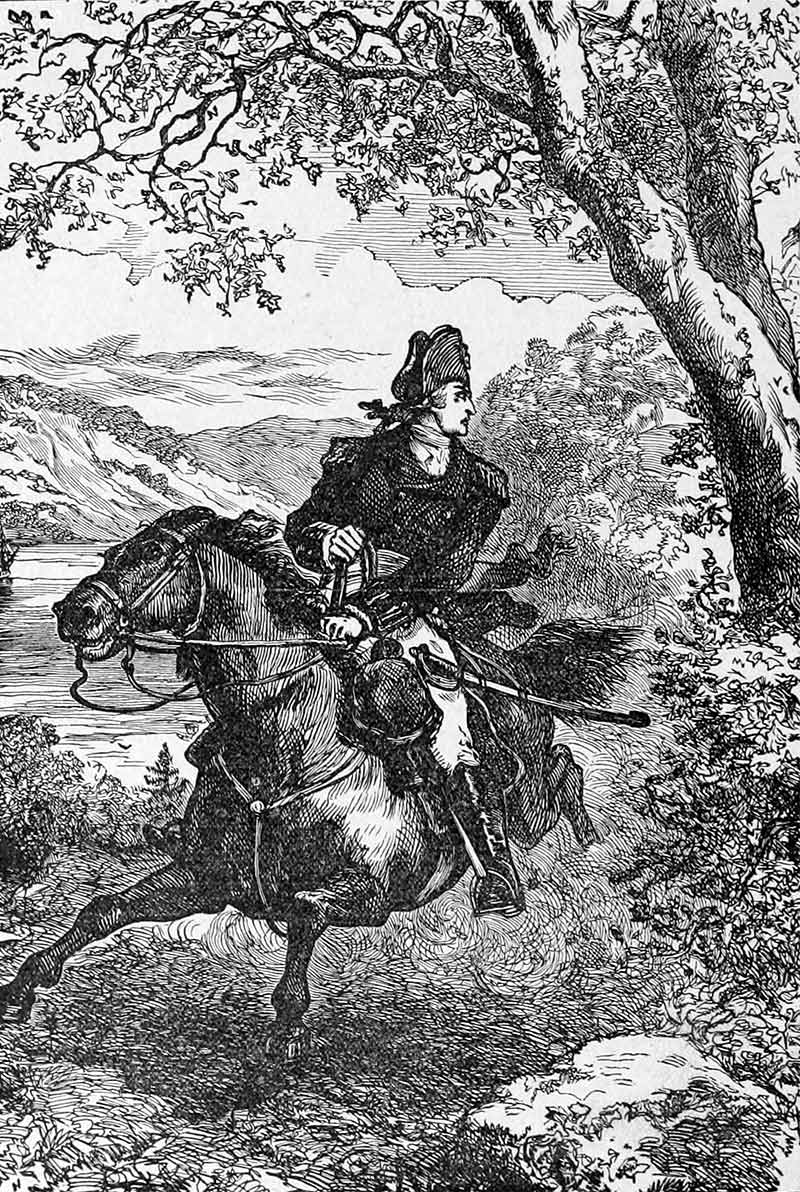

Sergeant Major John Champe (1752-1798) riding for his life to escape his own men and carry out Washington’s secret mission

No longer able to wait for a boat to bring him in, Champe, weighed down by full dragoon regalia, splashed through the marsh on the bank and plunged into the chilly river, determined to swim toward the vessels. As Middleton pulled up and cried out for Champe to surrender, marksmen aboard the ships opened fire. The Patriot dragoons fired back before being driven away. Friendly British hands reached down and hauled an exhausted Champe from the water. There was not a single one among them who doubted the credibility of a deserter with bullet holes on his coat.

He was taken into New York and brought before General Clinton, the man who had accepted Arnold into his ranks. Clinton was greatly impressed when he heard of the young sergeant’s adventure. Champe was only the second man ever to have deserted from Lee’s legion, a unit famed for its fidelity. Champe played along admirably, telling Clinton that Arnold’s defection would only be the first of many among the dispirited Americans. Clinton chatted with him for an hour, and he was particularly interested in knowing how fondly Washington was regarded by the troops, whether other senior officers seemed disaffected, and which measures might prompt large-scale desertions.

Once finished with his inquiries, Clinton recommended that Champe see Arnold, who was then busy raising a regiment of deserters and Tories. It was an unexpected offer, almost too fortuitous considering Champe’s real mission in New York, but one Champe could not refuse without causing great suspicion. General Arnold took an instant shine to the young man sent to abduct him, going so far as to make him a recruiting sergeant a day after he enlisted.

For several weeks, Champe paid close attention to his prey’s movements. Arnold’s house was situated on one of the city’s principal streets, which made it impossible to abduct him through the front door, but Champe noticed that Arnold had a habit of taking a midnight stroll in his back garden before going to bed. This garden bordered an obscure alley, a wooden fence separating the two. One night, Champe sneaked along the alley and loosened several slats to allow enough space for a man to pass through. At that point, he contacted one of the two incognitos provided by Lee and asked him to get a message across the Hudson to the Newark contact, whose task it was to tell Lee to have a boat and several dragoons waiting on a particular night on the Jersey shore. At a prearranged time, they were to row to a darkened, deserted Manhattan wharf and pick up Champe’s Arnold-sized “package.” Champe’s other New York contact would accompany Champe to the alley, and they would hide themselves in Arnold’s garden.

On the day Champe had chosen for the deed, he prepared his kit: a gag and a bar with which to bludgeon the general. The plan was to tackle Arnold, hit and silence him, push him through the fence, pull his hat down over his face, and hold him up with his arms sagging around their shoulders. To passersby, it would look like two friends taking their drunken friend home after a hard night. Once at the wharf, Arnold would be tied up and bundled into the boat, and Champe would make off with his fellow dragoons. The first face a groggy Arnold would have seen the next day would have been Washington’s vengeful one.

Benedict Arnold, however, was destined to be conspicuously spared from every attempt to bring him to account. Just as he had miraculously escaped being taken at West Point, he would do so again. The very evening that Champe was to kidnap the general, he discovered that Arnold had been suddenly transferred to new quarters to oversee the embarkation of his “American Legion” aboard naval transports, a result of General Clinton having issued emergency orders directing the legion to proceed to Virginia.

Champe, who was now a most unwilling part of that American Legion, was immediately confined to barracks with his fellows, and then marched to the docks to depart for the South. The only person being kidnapped, it seems, was Champe himself. The depth of his aggravation can only be imagined. Lee, meanwhile, had been impatiently waiting with his dragoons on the banks of the Hudson all night, and it was only a few days later that he realized that Champe would never be coming.

Months went by. Lee had no word of his man. Then, without any warning, a bedraggled, bearded Sergeant Champe appeared in Lee camp with a harrowing story to tell, but no Arnold to deliver.

It had come about that, after landing in his native Virginia, Champe had been obliged to fight against his compatriots to keep up the duplicitous front. Finding this existence insuperable and the likelihood of carrying out his mission increasingly futile, Champe had deserted Arnold’s Legion, for real this time. He hid out in the country, traveling only at night through Virginia and North Carolina to evade Loyalist sympathizers and British pursuers, until he had at last arrived back at his old regiment. Lee immediately called the regiment to muster and proceeded to narrate to their great astonishment the truth of Champe’s whereabouts, and that he had been acting under the commander-in-chief’s orders all along.

Then Lee took Champe to Washington, who, in place of the promised promotion, offered him a lavish bounty and a discharge from military service. Champe however, objected and pleaded vehemently with his General that he would like to rejoin his regiment, not at all too tired to see the war to its conclusion. Washington sagaciously counseled against any such notion: if Champe were to be taken prisoner by the British, he would inevitably be recognized and hung as a double agent. Forced to see the wisdom of this, Champe, his remarkable service done, bid farewell to his commanders and mounted the horse given to him by Washington. He went back to Loudoun County, Virginia, riding right out of our revolution’s narrative.

The last time anyone recorded seeing the mysterious Sergeant John Champe was sometime in the late 1780s when Angus Cameron, a Scottish captain in Arnold’s Legion, happened to get lost while traveling deep in the Loudoun County woods one summer night. A terrible storm rolled over him, and he spotted a cottage by the flash of the lightning—the first he had seen in many miles. The man of the house ushered him inside, a man strangely familiar to Cameron.

Cameron, it turns out, had been Champe’s old superior during his days in the Legion. “Sergeant Champe stood before me!”, Cameron later recalled, and his shock at seeing the audacious sergeant was not altogether pleasant. Champe was, after all, a two-time deserter. Cameron was an unarmed outsider hours away from help, and his host might not relish this blast from the past turning up unexpectedly. Cameron’s misgivings were, thankfully, misplaced. Champe remained the charmingly benign man he had always presented himself to be. “Welcome, welcome, Captain Cameron!” exclaimed Champe, upon recognizing the bedraggled guest he had opened his door to, “a thousand times welcome to my roof.”

Amongst the exuberant storytelling and good-natured argumentation of the night, Champe would assure Cameron that he had been “the only British officer of whose good opinion I was covetous”, owing to his kindly behavior toward him during the Virginia expedition. The war over and the threat of being found out gone, Champe chose Cameron as the only man to whom he told the entire plot. All other accounts we have of it come from Champe’s fragmented letters, Lee’s accounts, and the correspondence between Lee, Washington and Washington’s aides regarding it.

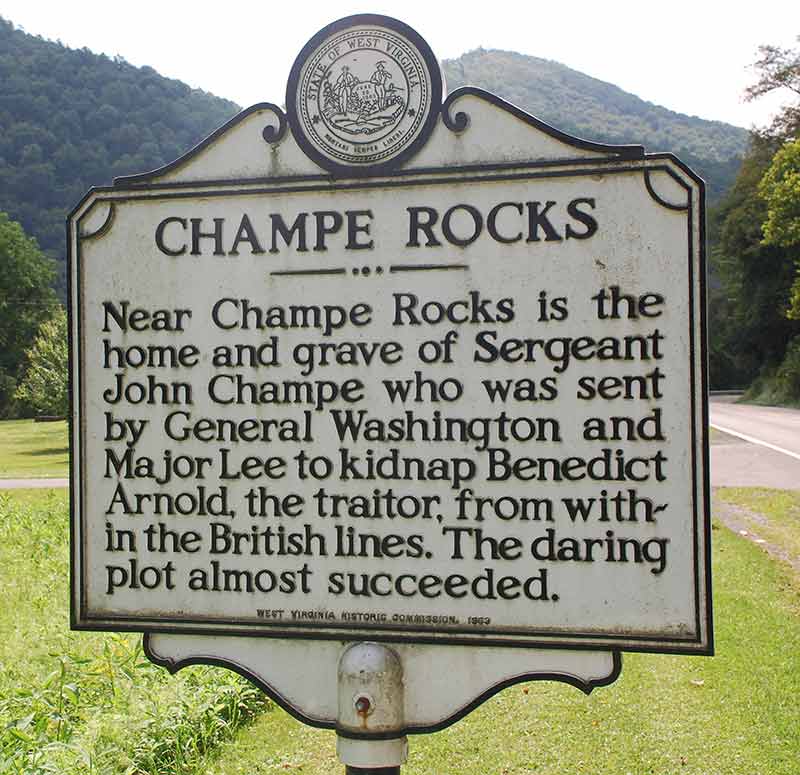

A marker at Champe Rocks in modern-day West Virginia commemorates the daring deeds of John Champe, and the rock formation named in his honor

A few years after Cameron’s visit to him, having since married and had six children, Champe moved to Hampshire County, Virginia (now in West Virginia). In 1798, while negotiating to buy land in Morgantown, on the banks of the Monongahela River, this remarkably modest man died and was buried in the soil he had once so bravely defended.

Champe Rocks in West Virginia, named in honor of John Champe

Image Credits: 1 Benedict Arnold (wikipedia.org) 2 Sir Henry Clinton (wikipedia.org) 3 Arnold’s oath of allegiance (wikipedia.org) 4 West Point Home (wikipedia.org) 5 Peggy (wikipedia.org) 6 Arnold’s escape (wikipedia.org) 7 Cipher letter (wikipedia.org) 8 Lee (wikipedia.org) 9 Escape of Sergeant Champe (wikipedia.org) 10 Champe Rocks Marker (wikipedia.org) 11 Champe Rocks (wikipedia.org)