“By the breath of God ice is given, and the broad waters are frozen fast. He loads the thick cloud with moisture; the clouds scatter His lightning. They turn around and around by His guidance, to accomplish all that He commands them, on the face of the habitable world. Whether for correction or for His land or for love, He causes it to happen.” —Job 37: 10-13

Robert F. Scott’s Expedition Reaches the South Pole, January 17, 1912

![]() he continent of Antarctica lived in our imaginations long before any report of her was made in recorded history. The Greeks of the ancient world, knowing of the existence of an Arctic, theorized of a corresponding Antarctic for the bottom of our planet. Maps from the Renaissance show the assumed presence of a great southern land mass “as yet undiscovered”. The Polynesian cultures encountered by European explorers, like James Cooke, told them of its great, uninhabitable expanse. With each passing century fascination grew, and soon the North and South Poles became the chief objects of conquest during a time now called the Heroic Age of Exploration. It was a time when those Christian countries, ever more intent on broadening their knowledge of God’s created world, sent out their sons to map its borders, convert its peoples, and document its scientific wonders.

he continent of Antarctica lived in our imaginations long before any report of her was made in recorded history. The Greeks of the ancient world, knowing of the existence of an Arctic, theorized of a corresponding Antarctic for the bottom of our planet. Maps from the Renaissance show the assumed presence of a great southern land mass “as yet undiscovered”. The Polynesian cultures encountered by European explorers, like James Cooke, told them of its great, uninhabitable expanse. With each passing century fascination grew, and soon the North and South Poles became the chief objects of conquest during a time now called the Heroic Age of Exploration. It was a time when those Christian countries, ever more intent on broadening their knowledge of God’s created world, sent out their sons to map its borders, convert its peoples, and document its scientific wonders.

A fragment of the Piri Reis map which dates back to 1513 and which some scholars believe depicts Antarctica

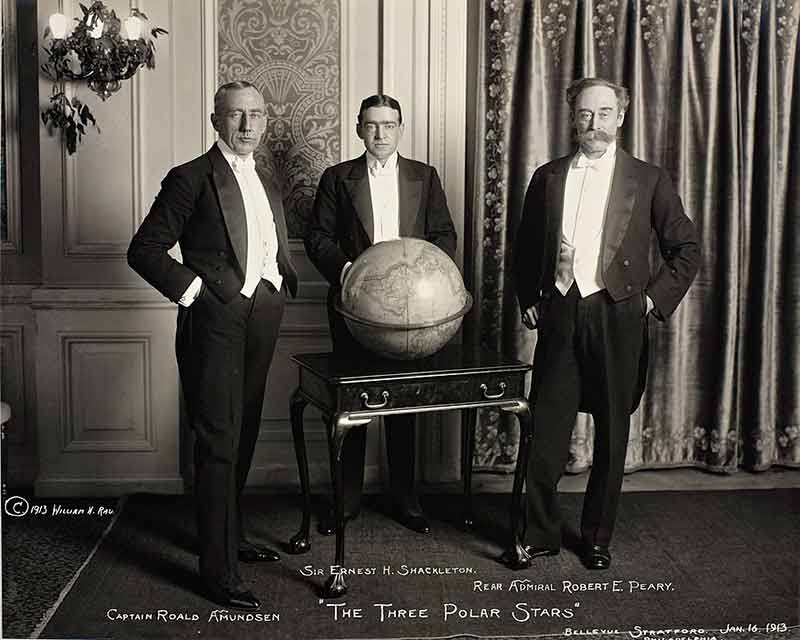

It can be hard for many of us to imagine the spirit that drove countless men from their comfortable homes to risk life and limb exploring what still remain the most inhospitable portions of our globe. Indeed, without immersing ourselves in the mindset of the time through means of books, we might even be mislead to minimize such great strivings as mere exercises in hubris. So much of our upbringing nowadays, our soft culture, and our system of immediate incentives, all work to dull us to that soul-dwelling drive which finds motivation and reward in that which is rigorous and unknown. But yet it remains, not much over a century ago, God and country was more than enough to spur many heroic men to achieve unfathomable feats by raw grit and endurance. Their names are familiar to some of us: Amundsen, Perry, Ross, Scott, to name a few.

L-R: Ernest Henry Shackleton, Captain Robert Falcon Scott and Dr. Edward Adrian Wilson on the British National Antarctic Expedition (Discovery Expedition), November 2, 1902

It was during this era that Teddy Roosevelt was preaching his doctrine of “the strenuous life”, that billionaires stepped aside on the decks of the Titanic and gave their seats up to the helpless so that chivalry might prevail. And when Ernest Shackleton could actually count on applicants to respond to his advertisement marketing his impending “hazardous journey.” Remarkable individuals were numerous in this remarkable age.

A photograph from 1913: The Three Polar Stars: Roald Amundsen (1872-1928), Ernest Henry Shackleton (1874-1922) and Robert Edwin Peary (1856-1920)

Geographical Societies sprung up to fund and organize such exploratory endeavors, and much of their success came from the support of ordinary men and women who considered the missions worthy of their patronage. By the turn of the 20th century, the frontier of the uncharted world had grown ever more remote and uninhabited, until there was, in the minds of many, only the Poles left to claim.

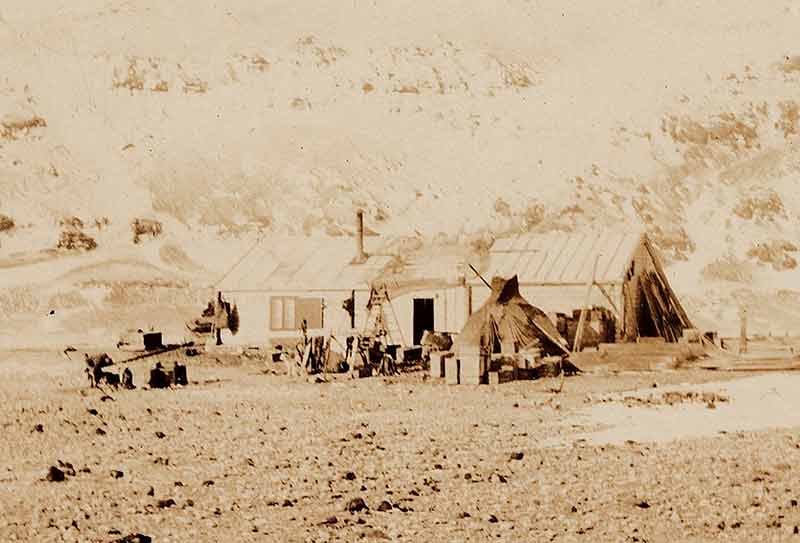

The first base on Antarctica of Carstens Borchgrevink’s Southern Cross Expedition of 1899. The hut still stands and is located on Cape Adare, the cape where, in 1895, Borchgrevnik participated in the first documented landing on Antarctica.

In 1909 the thrill of one such achievement rocked the world when the dogged American explorer, Robert Peary, shot off his sparsely worded telegraph from the North: “Stars and Stripes nailed to the pole. PEARY.” There went one frontier; only one more left to claim.

Peary’s team celebrating triumphantly at the North Pole

And so it fell to Captain Robert Falcon Scott, a seasoned Royal Navy officer who had already ventured far south on the Discovery expedition of 1901–1904, to lead Britain’s effort to conquer the last geographical prize. Aboard the whaling ship Terra Nova, Scott and his men departed England in June 1910, driven by scientific curiosity as much as national glory.

Portrait and signature of Robert Falcon Scott (1868-1912)

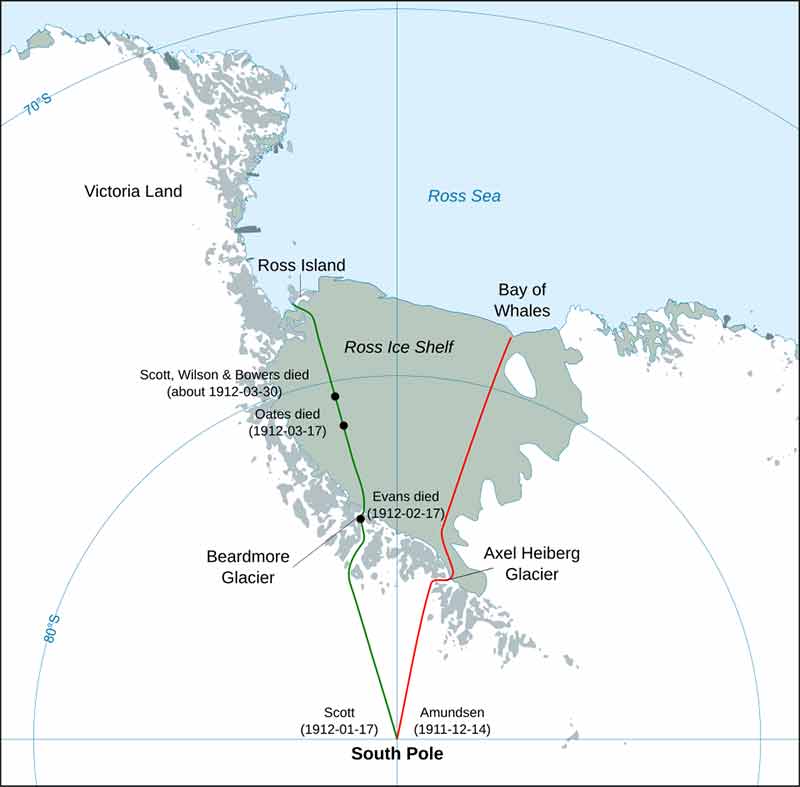

Upon reaching Antarctica, Scott learned he had a rival: the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, who had secretly redirected his own expedition southward after learning about Peary claiming the North Pole. Amundsen, a veteran polar explorer himself, relied on dogs, skis, and meticulous food depots, and he and four companions successfully reached the geographic South Pole before Scott on December 14, 1911.

The routes of the racing explorers and their expeditions: Scott (in green) and Amundsen (in red)

The Norwegians planted their flag and left behind a polite note for Scott to find, then started on their return trip of forty days.

Meanwhile, the party of five which Scott chose to accompany him overland on his eight-hundred-mile journey from the Terra Nova to the South Pole, had been chosen for their scientific prowess, rather than physical strength. It comprised Scott himself, Dr. Edward Wilson, Captain Lawrence Oates, Lieutenant Henry Bowers, and only one sailor, a Petty Officer Edgar Evans. Evans was chosen to accompany them at the very last minute, and as a result, provisions sufficient for only the original four men were taken along.

The five men who made up the Scott / Terra Nova Expedition, at the South Pole

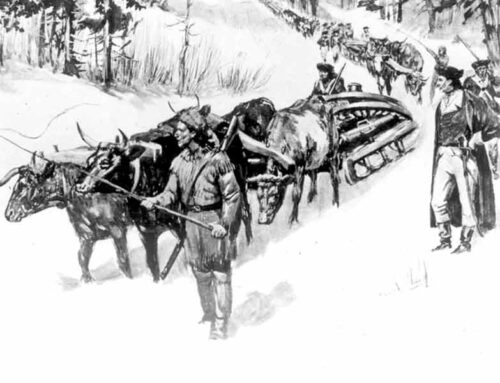

Scott’s brave party went towards their goal through brutal conditions that ruined their sled motors and killed their pack ponies, forcing the men to haul their sledges themselves with harnesses around their shoulders. They were short of food before they had even reached the Pole, scurvy was further weakening them, and their Royal Navy-issued woolen accoutrements were insufficient to withstand the cold—in contrast, the Norwegians had adopted Inuit forms of apparel, liberally equipping themselves in heavy furs and waterproof seal skins. Despite all such strategic shortcomings and incidental disadvantages, Scott pressed on.

Roald Amundsen modeling the clothing and gear that gave his expedition such great success; “Not an outfit that cut a dash by its appearance, but it was warm and strong”

And then, on January 17, 1912, they finally reached their goal—the South Pole! But no, this is not a story where the glorious payoff exceeds the tribulations endured to reach it. For upon arriving, Scott’s exhausted party found Amundsen’s tent and the Norwegian flag awaiting them at the exact spot, evidence that they had been preceded by thirty-four days.

Roald Amundsen and Helmer Hanssen make observations at the South Pole, having arrived on December 14 and staying for several days

In much misery, standing on a frozen plain of nothingness, without even the balm of having first staked it for England, Scott wrote in his diary: “Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority.”

Members of the dejected Terra Nova exploration team explore Roald Amundsen’s tent at the South Pole on January 18, 1912—L-R: Scott, Oates, Wilson, Evans (Bowers behind the camera)

Disheartened but resolute, the five men began the long return, but it was predictably disastrous. Touchingly they still prioritized the photographs, fossils and thirty-five pounds’ worth of geological specimens they had accumulated, on the journey back.

The entire Terra Nova exploration team at the camp the Norwegians left behind at the South Pole

Like so many tragedies, the Scott Expedition would become famous, not for being second best, but for the noble way in which it ended: discouraging, miserable and lonely though it was, these were men who knew how to die well. Even in the vast secrecy of a frozen continent, they knew their God was with them, and they left a worthy record as a result.

Scott and his men on their return trip

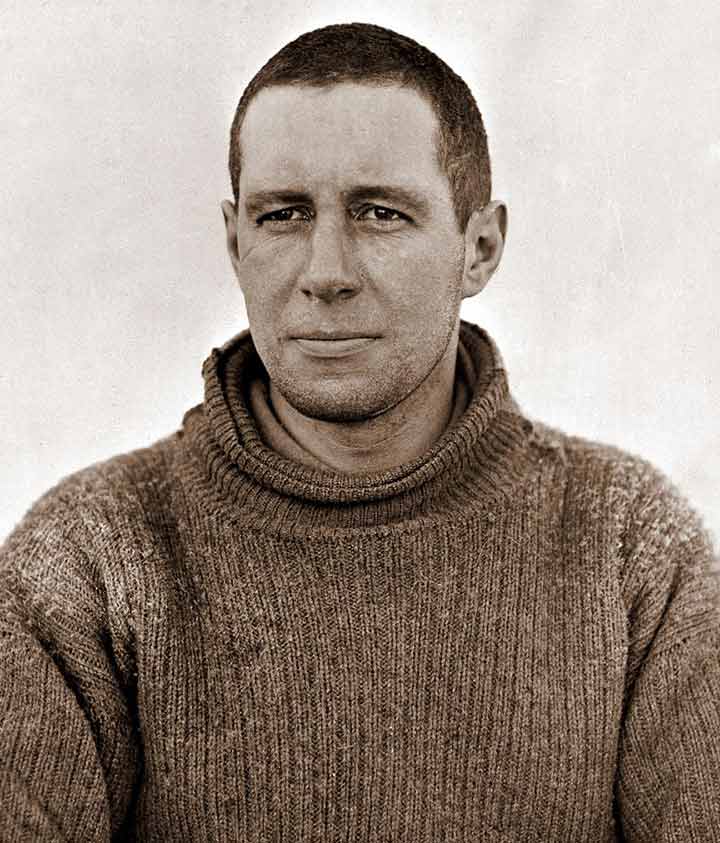

The seaman Evans perished first on February 17, succumbing to a concussion. Oates, crippled by frostbite, sacrificed himself on March 16 or 17, walking into a blizzard with the immortal words, “I am just going outside and may be some time.” The remaining three—Scott, Wilson, and Bowers—were later trapped by relentless blizzards in their tent, a tragic eleven miles short of their next supply depot.

Lawrence Oates (1880-1912)

One of the camps of the Terra Nova expedition

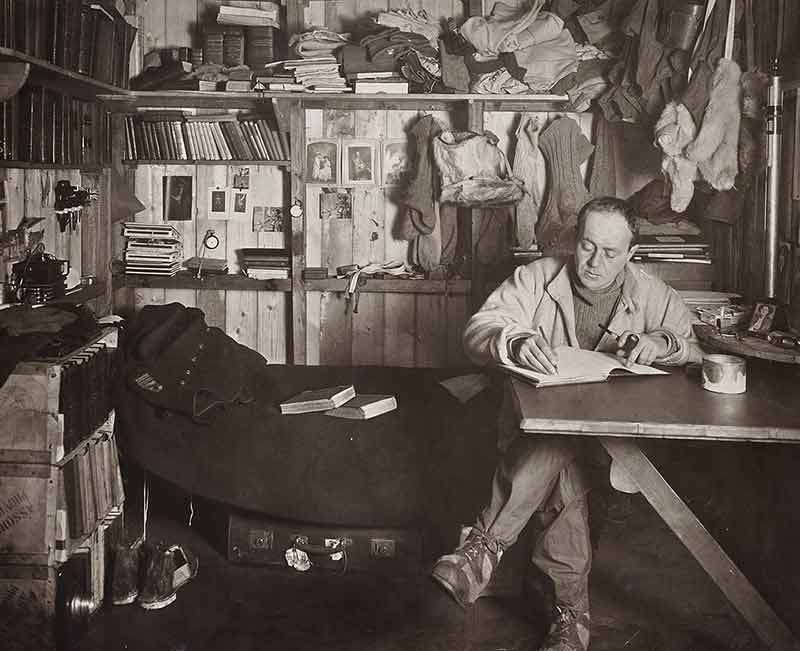

Knowing death by malnutrition and exposure was imminent, Robert Falcon Scott—captain, husband, father and Christian—chose to write a most remarkable “message to the public.” In it he did not wallow in self-pity or aggrandize the great scientific work he had achieved on this venture. Instead he meticulously enumerated the details of the journey and immortalized his fellows, the men who had labored, suffered disappointment, and eventually died beside him, regarding themselves as “part of the great scheme of the Almighty.” And most heart-rending of all, he begged for their families to be looked after.

Scott journaled faithfully on his expeditions, not the least of which was his last

To the general public, Scott wrote:

“We are weak, writing is difficult, but for my own sake I do not regret this journey, which has shown that Englishmen can endure hardships, help one another, and meet death with as great a fortitude as ever in the past. We took risks, we knew we took them; things have come out against us, and therefore we have no cause for complaint, but bow to the will of Providence, determined still to do our best to the last. But if we have been willing to give our lives to this enterprise, which is for the honour of our country, I appeal to our countrymen to see that those who depend on us are properly cared for. Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale, but surely, surely, a great rich country like ours will see that those who are dependent on us are properly provided for.”

Scott

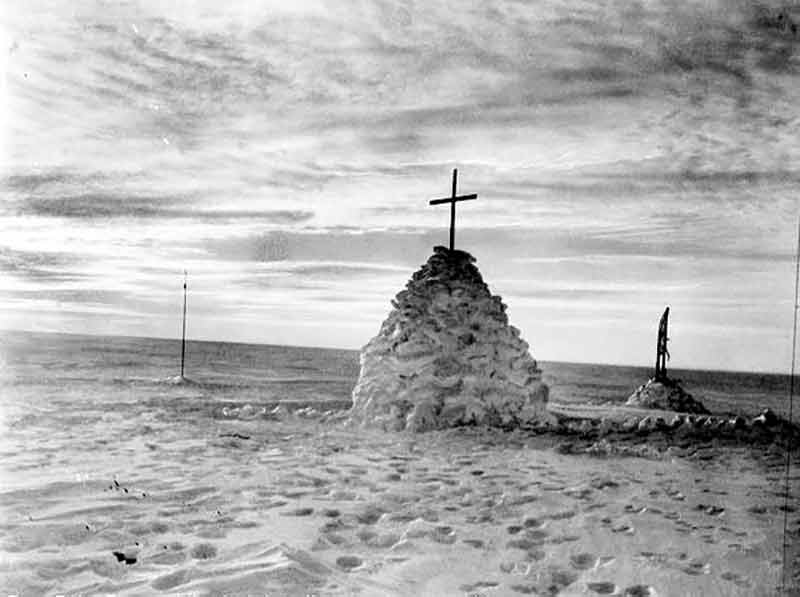

Their bodies, journals, and photographs were discovered eight months later by a search party, their effects returned to their families, and their last words enshrined in history. His wife, the unwavering Kathleen Scott, raised their son Peter to revere his father and he followed him into the Navy. Kathleen’s work as a remarkable sculptress can be seen etched into marble across England, her hand having helped craft memorials to her husband and to those 880,000 British men who similarly sacrificed their lives for their country during the Great War.

The location where the bodies of the last three members of the expedition were found—their personal effects were removed, their tent lowered over them,

and this memorial erected

Although Amundsen claimed the final prize of polar conquest, Scott’s tragic striving captured the world’s imagination, embodying the unyielding spirit of an age that feared death far less than the waste of a stagnant life.

The frozen, barren, unforgiving wasteland, Antarctica

Image Credits: 1 Piri Reis map (wikipedia.org) 2 Shackleton, Scott, Wilson (wikipedia.org) 3 “The Three Polar Stars” (wikipedia.org) 4 Southern Cross camp, 1899 (wikipedia.org) 5 Peary’s expedition at the North Pole (wikipedia.org) 6 Robert Falcon Scott (wikipedia.org) 7 Scott / Amundsen routes (wikipedia.org) 8 Scott team at South Pole (wikipedia.org) 9 Amundsen in gear (wikipedia.org) 10 Norwegian team making observations (wikipedia.org) 11 Exploring Amundsen’s camp (wikipedia.org) 12 The Scott team (wikipedia.org) 13 Scott’s team on the return (wikipedia.org) 14 Lawrence Oates (wikipedia.org) 15 Terra Nova team camp (wikipedia.org) 16 Scott journaling (wikipedia.org) 17 Scott (wikipedia.org) 18 Grave / Memorial (wikipedia.org) 19 Antarctica (wikipedia.org)