The Tet Offensive in Vietnam War Begins, 1968

“There are six things that the LORD hates, seven that are an abomination to him: haughty eyes, a lying tongue, and hands that shed innocent blood, a heart that devises wicked plans, feet that make haste to run to evil, a false witness who breathes out lies, and one who sows discord among brothers.” —Proverbs 6:16-19 (ESV)

The Tet Offensive in Vietnam War Begins, January 30, 1968

![]() he United States had gotten involved in Vietnam in the early 1950s after the French, who had dominated the region for many years, were defeated by the indigenous communist forces known as the Viet Minh. The Cold War between the Western nations and the Communists of Russia and China spanned the globe. American foreign policy dictated trying to keep small countries from succumbing to international communist aggression and it appeared that Vietnam was ripe to fall into the Red orbit. Thus, the United States backed anti-communist forces of South Vietnam with weapons, money and influence during the Eisenhower years. Under Presidents Kennedy, and, especially, Johnson, American support for the South Vietnamese government and army (ARVN) increased exponentially and included troop commitments.

he United States had gotten involved in Vietnam in the early 1950s after the French, who had dominated the region for many years, were defeated by the indigenous communist forces known as the Viet Minh. The Cold War between the Western nations and the Communists of Russia and China spanned the globe. American foreign policy dictated trying to keep small countries from succumbing to international communist aggression and it appeared that Vietnam was ripe to fall into the Red orbit. Thus, the United States backed anti-communist forces of South Vietnam with weapons, money and influence during the Eisenhower years. Under Presidents Kennedy, and, especially, Johnson, American support for the South Vietnamese government and army (ARVN) increased exponentially and included troop commitments.

Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-1973) in the Oval Office, 1964

As the war muddled along, factions in the North Vietnamese political system argued over the best strategy for victory. The most aggressive militarists gained the upper hand and planned a sweeping strategy to destroy the ARVN forces, kill as many Americans as possible, and bring the government to their knees in one campaign. They organized the local communist peasant cadre in the South (Viet Cong) to join with the North’s regular trained army, in a three-phase offensive to be launched during the celebration of the Vietnamese New Year celebrations — Tet. Although U.S. Intelligence suspected some large military effort, the Americans and their allies were not prepared for the size and coordination of the attack which launched on January 30, 1968.

Johnson awards the Distinguished Service Cross during his visit to Vietnam in 1966

80,000 communist troops struck on the first day, 84,000 more on the second. They attacked one hundred towns and cities as well as American fire-bases, and six major targets in the capital city of Saigon, including the American Embassy. Using mortars and rocket-propelled grenades, and carrying AK-47s, the initial assaults were beaten back. No line broke, and no South Vietnamese units defected — an initial failure for the aggressors. By the end of the first phase of the offensive, the communist forces had lost about 45,000 killed. It cost 11,000 ARVN casualties and just under 9,000 Americans, with about 1,500 killed. By the end of the third phase, the North Vietnamese high command had to call off the disastrous Tet Offense which had cost them massive casualties.

Civilians in Cholon, the heavily damaged Chinese section of Saigon, sort through the ruins of their homes in the aftermath of the Tet Offensive conflict

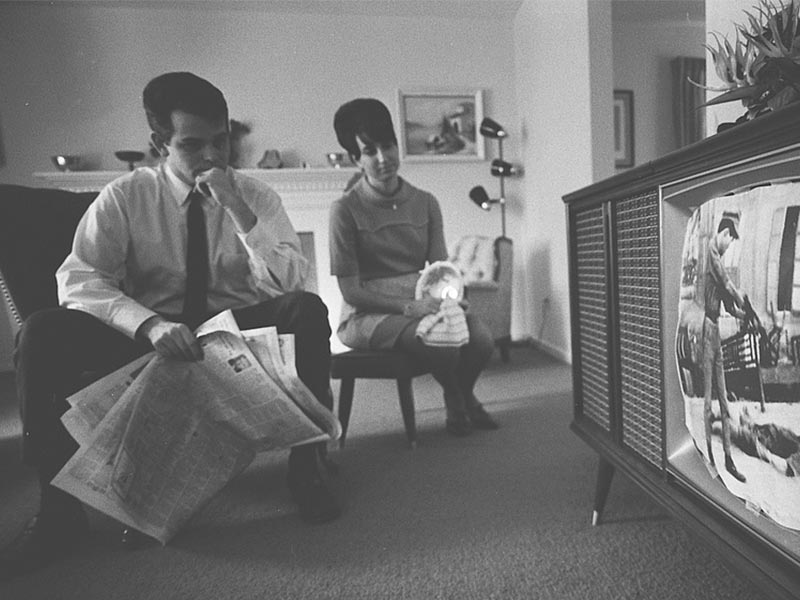

The Tet offensive was a total military failure for the communist Viet Minh. Nonetheless, the American press turned it into a North Vietnamese victory before the American people by providing breathless and dramatic, near or on-the-scene reporting via television. The pictures of slaughter and mayhem were brought into American homes night after night on the daily news. The stories they chose to tell and the images that reinforced their message, made the television editors the architects of historical interpretation. There is no such thing as objective reporting. They report, they decide, what they want the people to believe. Because the government had lied often about the war, the power of the press trumped anything that Washington might say to mitigate the criticism.

An American couple watches Vietnam War media coverage from their living room

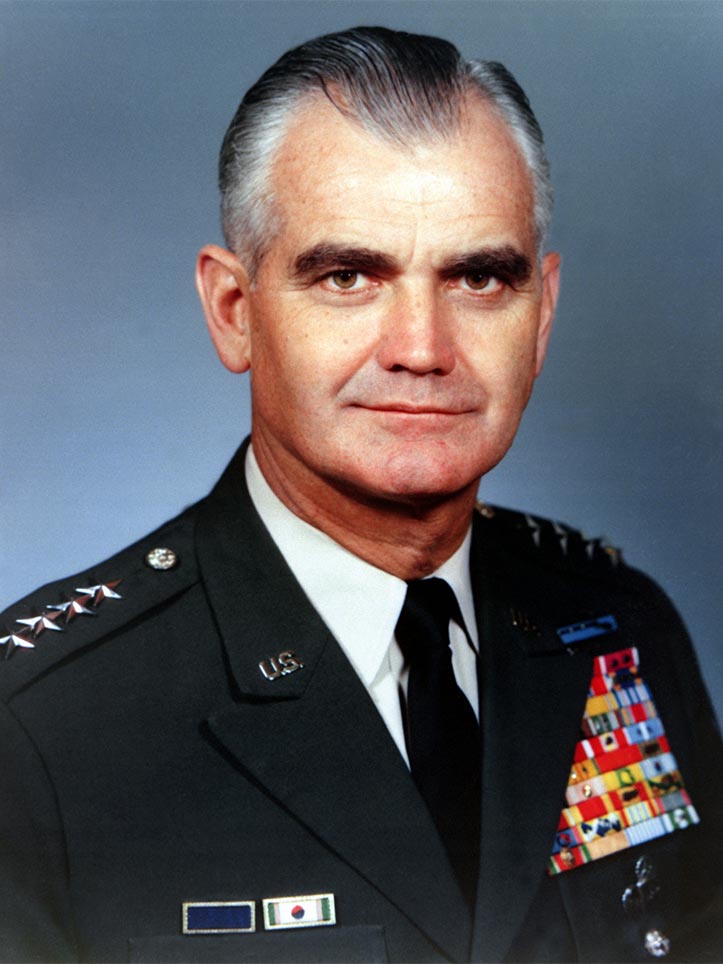

The selective coverage of the North Vietnamese “Tet Offensive” animated the anti-war movements of America, and put decisive pressure on the Congress and the President, by bringing the war to the living rooms of America. President Johnson replaced the commander, General Westmoreland, but did not survive the political blowback from the results of the battle, and decided not to run for President again. Although militarily, the destruction of the Tet Offensive seemed like the beginning of the end for the communists, it proved rather the beginning of the end of the Democratic Party ascendency in the Executive branch, and the radicalization of the anti-war movement in the U.S.

General William Westmoreland (1914-2005)

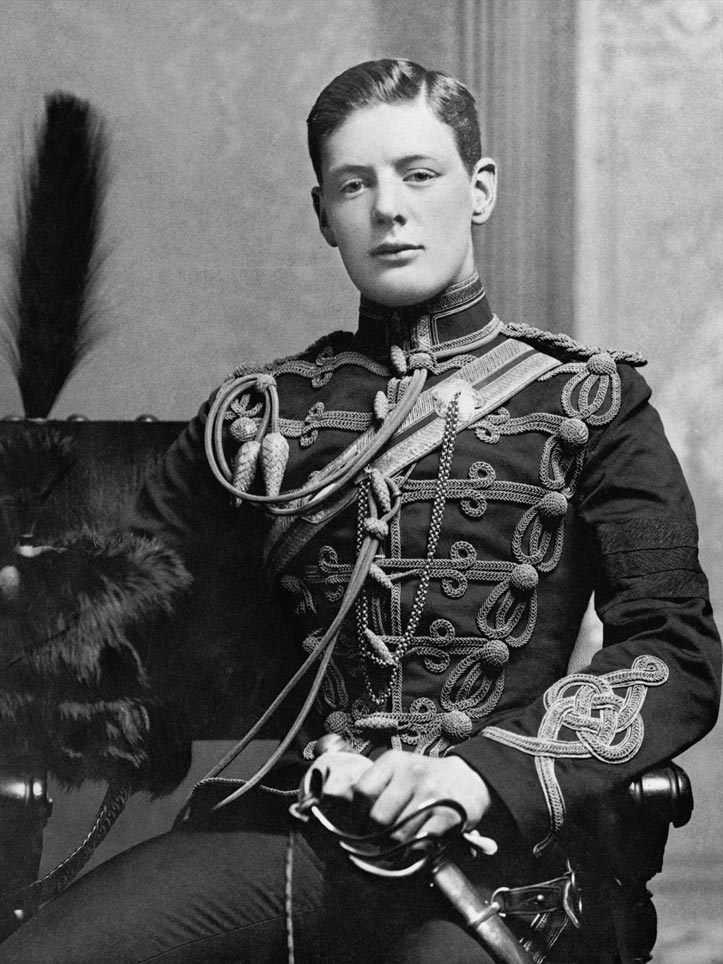

he history of the world is but the biography of great men,” wrote Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle. He was articulating the widespread belief that certain historical characters — through their leadership, wisdom, political power, or transcendent skills — influenced or shaped history in decisive ways. Although that theory fell in to disuse and abuse in the past century, one can hardly deny that there are elements of truth in the idea. Scripture demonstrates that certain individuals were raised up by God to glorify Him in particular ways that determined — from a human perspective — the direction of history. Moses, the Pharaoh, King David, Nebuchadnezzar, among numerous others, illustrate the point. I would suggest that Winston Churchill’s influence on the 20th Century made a decisive difference in the direction of the world history.

he history of the world is but the biography of great men,” wrote Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle. He was articulating the widespread belief that certain historical characters — through their leadership, wisdom, political power, or transcendent skills — influenced or shaped history in decisive ways. Although that theory fell in to disuse and abuse in the past century, one can hardly deny that there are elements of truth in the idea. Scripture demonstrates that certain individuals were raised up by God to glorify Him in particular ways that determined — from a human perspective — the direction of history. Moses, the Pharaoh, King David, Nebuchadnezzar, among numerous others, illustrate the point. I would suggest that Winston Churchill’s influence on the 20th Century made a decisive difference in the direction of the world history.

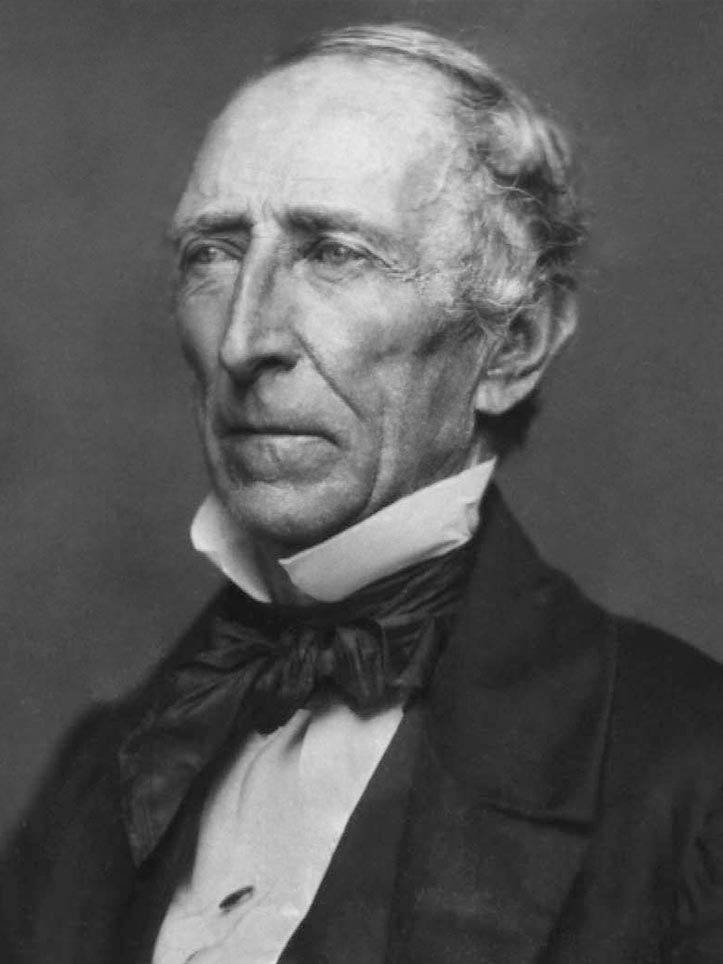

is funeral was the largest ever held in Richmond, Virginia. President John Tyler (1790-1862) was the only President who died not a citizen of the United States — he was serving in the Congress of the Confederacy at death. He is known in the presidential trivia contests for all of his firsts: first vice-president to accede to the office of president upon the death of the incumbent, first president to marry in the White House, certainly the number one family man president with fifteen children, “to whom he was an attentive and loving father.” Dig a little deeper than presidential trivia and you find one of the strictest Constitutionalists to hold that office, and groomed to be so by his father.

is funeral was the largest ever held in Richmond, Virginia. President John Tyler (1790-1862) was the only President who died not a citizen of the United States — he was serving in the Congress of the Confederacy at death. He is known in the presidential trivia contests for all of his firsts: first vice-president to accede to the office of president upon the death of the incumbent, first president to marry in the White House, certainly the number one family man president with fifteen children, “to whom he was an attentive and loving father.” Dig a little deeper than presidential trivia and you find one of the strictest Constitutionalists to hold that office, and groomed to be so by his father.

ith the election of President James K. Polk came Texas annexation and the advancement of American “Manifest Destiny,” a widely accepted theory that the United States was destined to control the North American continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans. After Mexico rebuffed the offer by the American government to purchase Mexican land — including California and the Southwest — American troops moved into the territory between the Rio Grande and Nueces Rivers, a much disputed area claimed by both Texas and Mexico. Fighting broke out between soldiers and civilians of the two nations, and Congress declared war on Mexico.

ith the election of President James K. Polk came Texas annexation and the advancement of American “Manifest Destiny,” a widely accepted theory that the United States was destined to control the North American continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans. After Mexico rebuffed the offer by the American government to purchase Mexican land — including California and the Southwest — American troops moved into the territory between the Rio Grande and Nueces Rivers, a much disputed area claimed by both Texas and Mexico. Fighting broke out between soldiers and civilians of the two nations, and Congress declared war on Mexico.

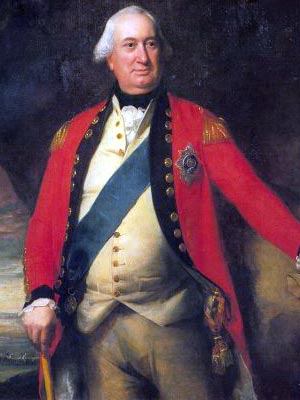

s Christmas approached, the cause of American independence seemed as bleak as the winter that descended on New Jersey and Pennsylvania. George Washington’s army lay frozen in their camps, riddled with disease and disintegrating by desertions. They had been driven from New York after serial defeats and heavy losses, with little or no prospects for improving their position near the Delaware River. Congress began planning to flee Philadelphia as soon as the weather cleared and the coming of the expected British campaign to take the American capitol. Patriotic morale was on its death bed when the General called his officers together to announce a secret winter attack.

s Christmas approached, the cause of American independence seemed as bleak as the winter that descended on New Jersey and Pennsylvania. George Washington’s army lay frozen in their camps, riddled with disease and disintegrating by desertions. They had been driven from New York after serial defeats and heavy losses, with little or no prospects for improving their position near the Delaware River. Congress began planning to flee Philadelphia as soon as the weather cleared and the coming of the expected British campaign to take the American capitol. Patriotic morale was on its death bed when the General called his officers together to announce a secret winter attack.