“Mine enemies would daily swallow me up: for they be many that fight against me, O thou most High. What time I am afraid I will trust in thee.” —Psalm 56:2,3

The Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777

s Christmas approached, the cause of American independence seemed as bleak as the winter that descended on New Jersey and Pennsylvania. George Washington’s army lay frozen in their camps, riddled with disease and disintegrating by desertions. They had been driven from New York after serial defeats and heavy losses, with little or no prospects for improving their position near the Delaware River. Congress began planning to flee Philadelphia as soon as the weather cleared and the coming of the expected British campaign to take the American capitol. Patriotic morale was on its death bed when the General called his officers together to announce a secret winter attack.

s Christmas approached, the cause of American independence seemed as bleak as the winter that descended on New Jersey and Pennsylvania. George Washington’s army lay frozen in their camps, riddled with disease and disintegrating by desertions. They had been driven from New York after serial defeats and heavy losses, with little or no prospects for improving their position near the Delaware River. Congress began planning to flee Philadelphia as soon as the weather cleared and the coming of the expected British campaign to take the American capitol. Patriotic morale was on its death bed when the General called his officers together to announce a secret winter attack.

On the night of December 25, Washington and 2,400 men stealthily cross the Delaware River in preparation for a morning attack on the Hessian garrison in Trenton

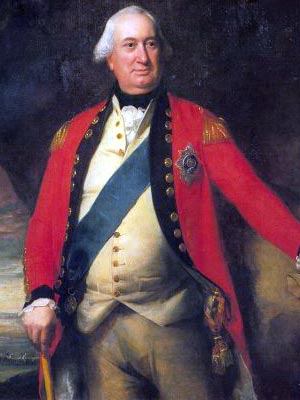

During the night of December 25-26 Washington’s army rowed across the Delaware River to New Jersey and charged into Trenton, surprising the Hessian garrison there. The mercenaries were routed and the British army commander, Lord Cornwallis, discomfited, though safe behind his New York defenses. Smashing a major British outpost in a surprise attack, at the most unlikely moment, cheered Americans as no other event could have done.

The Capture of the Hessians at Trenton, December 26, 1776

Cornwallis left his cozy billet in New York City and marched a 9,000-man force south to crush Washington’s brazen 6,000. On the night of the 2nd of January, the Americans left their campfires burning and a token force to skirmish with the British over Assunpink Creek, and slipped around Cornwallis’s flank, silently marching the back roads to surprise the 1,400-man force the British had left at Princeton, New Jersey. Again, Washington had surprised an inferior number of men with a preponderance of his own forces. As Providence would have it, Colonel Mawhood in command of the British regiments, had called off the patrols along the very roads from which the Americans were approaching the British lines.

Lord Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805)

Unknown to Washington, on the other hand, Cornwallis had called for Mawhood to bring his troops to join with the main body of the army. Two British regiments spotted Washington’s men approach to Princeton and turned on them. American Brigadier General Hugh Mercer’s troops were suddenly outnumbered and overrun by the British light infantry. Mercer died fighting. When the militia under Colonel Cadwalader came up to help and saw Mercer’s men fleeing, they joined in the stampede.

The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton

At the crucial moment, Washington rode up leading the Virginia Continentals and the Maryland Line, and he rallied the fleeing militia. With General Washington out front, both opponents’ battle lines halted and fired a volley at each other. The smoke obscured the field. When it cleared, Washington was untouched and waving his men forward with hat in hand. The British were driven from the field in disorder. In the town, some enemy soldiers barricaded themselves inside Nassau Hall on the Princeton College campus. They refused to give up until Alexander Hamilton had his three artillery pieces fire on the building as the infantry rushed forward. A white flag appeared and 194 redcoats came out with their hands up.

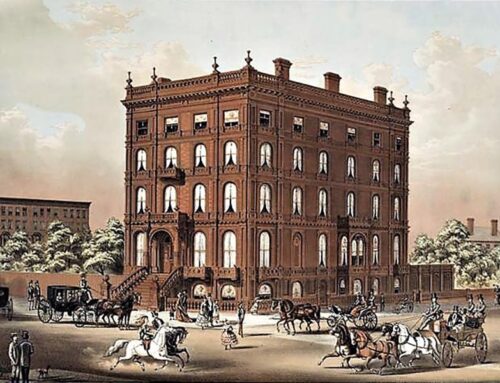

Built in 1756, Nassau Hall is the oldest building in what is now Princeton University

Washington rallies his troops at the Battle of Princeton

At a cost of less than a 100 men, Washington had caused 300-400 British casualties and bolstered American morale in incalculable ways. General Washington lost many battles, some of them very closely run, but his back-to-back victories in the harsh winter of ’77, proved that perseverance, overcoming hardship, and victory at the right moment can be of importance far beyond the disappointments of previous defeats.

English historian George Otto Trevelyan summed up the results of Trenton and Princeton this way:

“It may be doubted whether so small a number of men were ever employed in so short a space of time with greater and more lasting effects upon the history of the world.”

Save the Dates!

Join us September 17-22 when we visit Princeton, Brandywine, Valley Forge and the Delaware Crossing site as part of our 2018 Cradle of Liberty Tour! More tour details coming soon!