Isabella MacDuff Crowns Robert the Bruce, 1306

Isabella MacDuff Crowns Robert the Bruce,

March 26, 1306

![]() ince the overthrow of the infamous Macbeth’s usurpation, Scotland’s rightful kings were crowned by a member of the clan MacDuff. From 1058 onward, one after another, members from this proud family had been given the honor of leading Scotland’s vanguard in battle and placing the crown on the head of God’s anointed. But in 1306, Scotland was running out of kings, lawful or potential.

ince the overthrow of the infamous Macbeth’s usurpation, Scotland’s rightful kings were crowned by a member of the clan MacDuff. From 1058 onward, one after another, members from this proud family had been given the honor of leading Scotland’s vanguard in battle and placing the crown on the head of God’s anointed. But in 1306, Scotland was running out of kings, lawful or potential.

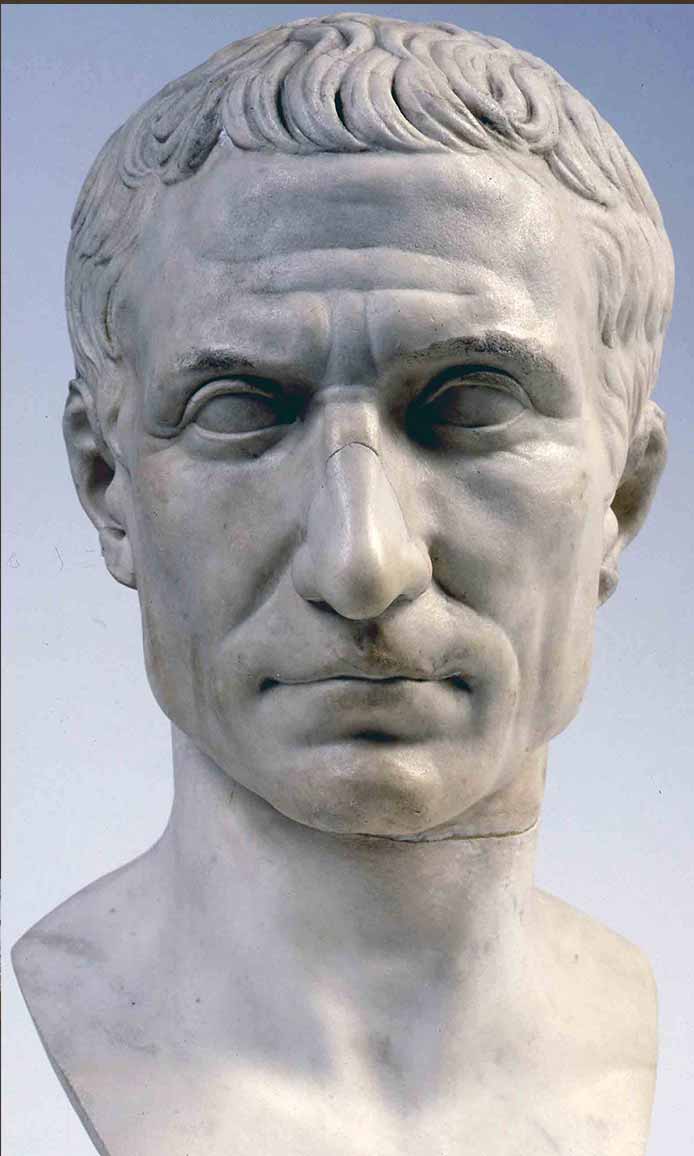

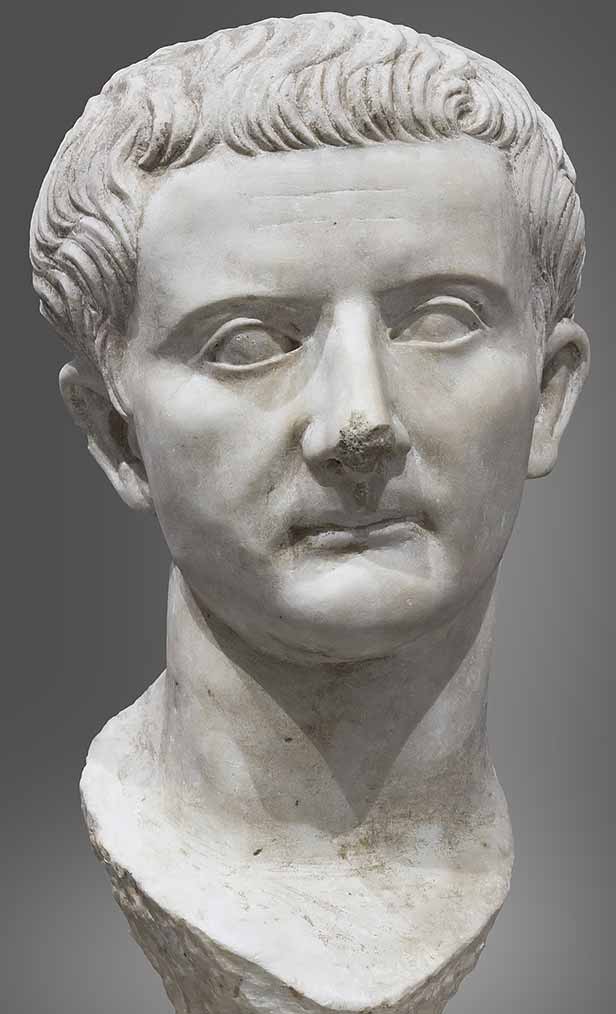

Robert the Bruce (1274-1329)

One of the last claimants was Robert the Bruce, an outlawed hero in his own terrorized country, he was in the midst of carrying on the bitter war against England that the martyred William Wallace had begun. Harried from his home, losing brothers to the English axe, excommunicated by the pope and facing charges of murder, Robert the Bruce had little to recommend his claim beyond his birthright and a promise to free his people once and for all from English rule. For himself it was a matter of winning the throne—or death.

He had the support of the bishop of St. Andrew, a wise and pious man who did not bow to the politics of Rome that censored all Scots as “rebels.” This was favorable for the Bruce as a bishop was needed for a coronation. A circle of gold was hastily made to replace the crown of Scotland that their enemy Edward I had carried off, along with the Stone of Destiny upon which Scottish kings were crowned. Painstakingly these customs were accumulated, recreated or forged to make Bruce a king. But what of the civic realm? Where were the essential and revered MacDuffs to validate the heir of choice?

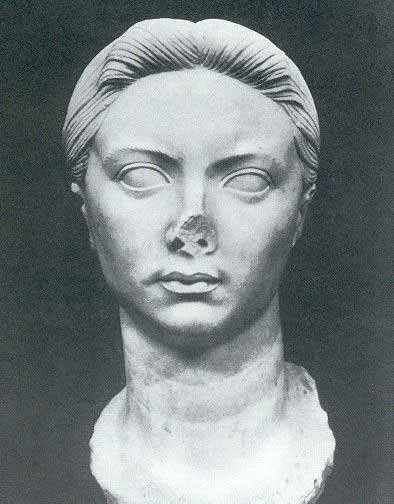

Bruce and his first wife, Isabella of Mar (1277-1296)

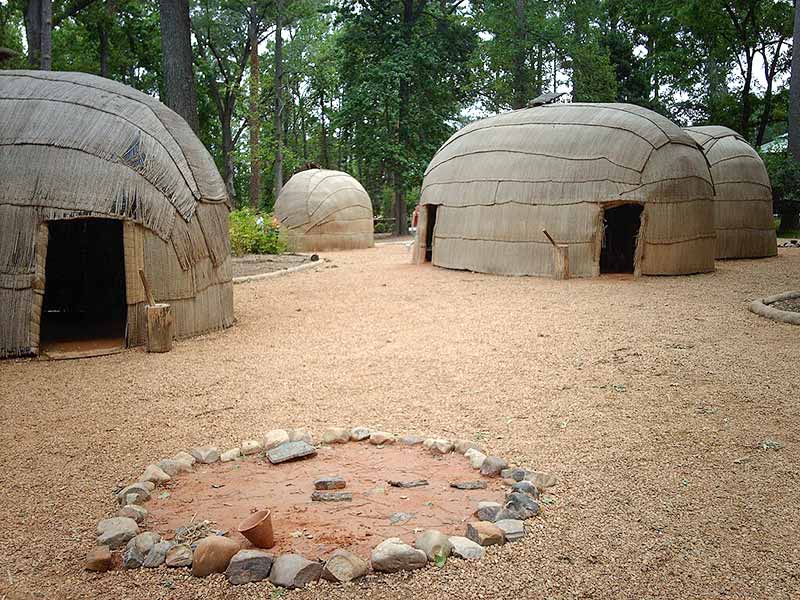

MacDuff Castle and the Wemyss Caves, Fife, Scotland

Many MacDuffs had been slain in the recent wars of independence, and some were imprisoned in England. Furthermore many had chosen sides with the English against the Bruce after his killing of their kinsman, The Red Comyn, in a feud. All seemed lost in regard to the MacDuffs and the Bruce’s hasty coronation at Scone Abby—ancient site of Scottish kings—appeared ever more presumptuous and invalid, until the arrival in his camp of a most unexpected validator: Isabella MacDuff.

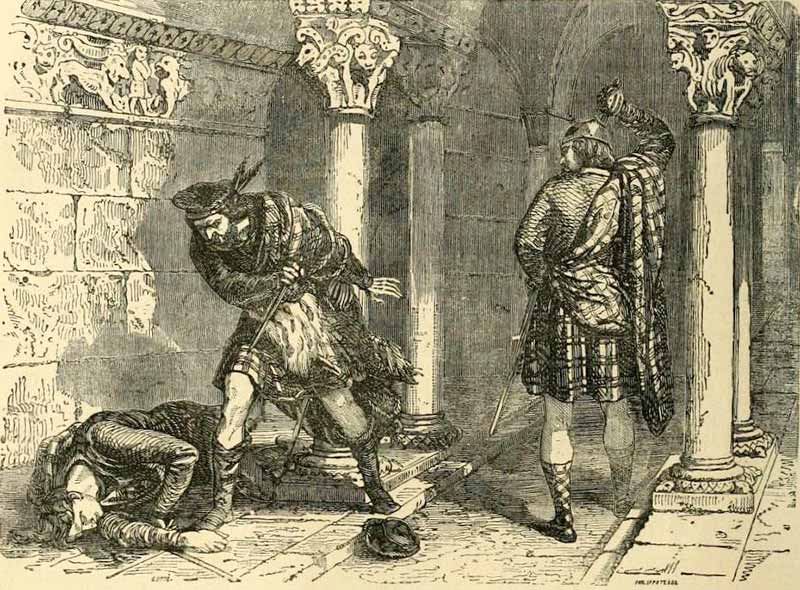

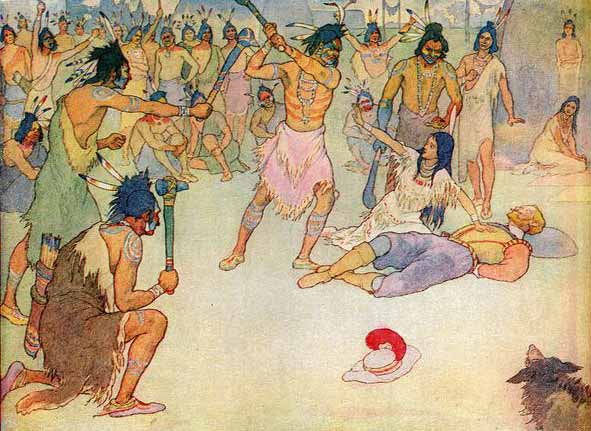

John Comyn is killed by Robert Bruce and Roger de Kirkpatrick, Greyfriars Church, Dumfries, Scotland, 1306

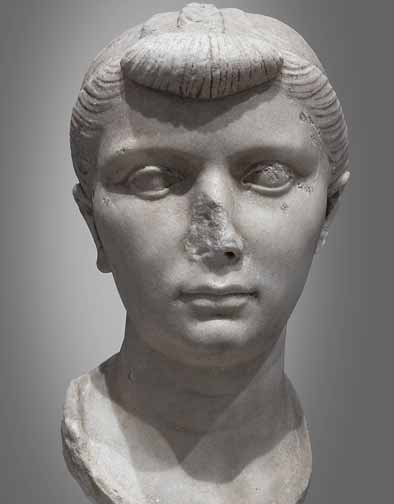

A day late, and without permission from her husband who had chosen the English side, the sudden support of Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan, was of such importance that Bruce agreed to run the whole ceremony again. The crowning of the day before was scrapped and with great to-do Bruce knelt once again to be charged before God and man to do his duty, with Isabella MacDuff carrying out her family’s role in placing the circlet on his head.

Isabella MacDuff places the crown upon the head of Robert the Bruce

The MacDuffs’ role in these ceremonies had great traditional and symbolic significance in substantiating the sovereign’s power as coming from the pleasure of the Scottish people, their subjects and their under-lords. Just as the first MacDuff had judged Macbeth to be a murdering usurper and crowned the ousted Prince Malcom instead, so Isabella refuted Edward I’s claim to Scotland’s throne and chose the most likely champion left her.

Notable Figures in the First Scottish War of Independence—(L-R) Robert the Bruce; Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan; William Wallace. Detail from a frieze in the entrance hall of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland

This defiance would cost both Isabella and the Bruce greatly in the coming years. No glorious reign commenced after she crowned him. Instead there were years of guerrilla fighting in the wilderness of Scotland, bounties on the heads of all who supported the new king, and abandonment by relatives.

Bruce entrusted his young wife and sisters to the care of Isabella as he traveled north into the highlands to gain support. Isabella intended to follow, but she and the Bruce ladies were betrayed to the English by a Scottish lord, the Earl of Ross, and were sent into captivity. Their enemy King Edward I of England was delighted at having such hostages: the Bruce’s wife, his daughter, two sisters and the woman who dared crown him. They were offered clemency if they renounced him. None would.

Chapel at Moot Hill, Scone, Scotland which was the inauguration site of the Scottish Kings

Edward’s punishment for this was to imprison them in cages, hung from the sides of various prestigious castles, exposed to weather, ridicule and constant observation. His own decree for Isabella’s treatment reads thus:

“Let her be closely confined in an abode of stone and iron made in the shape of a cross, and let her be hung up out of doors in the open air at Berwick, that both in life and after her death, she may be a spectacle and eternal reproach to travellers.”

Isabella MacDuff would endure such captivity for four long years. When Bruce finally gained support and won a series of victories in Scotland, her treatment and that of the Bruce ladies improved, their roles being turned from gruesome warnings to valuable bargaining chips—better alive than dead.

The earliest known depiction of the Battle of Bannockburn from a 1440s manuscript— Robert the Bruce is portrayed wielding a battleaxe and riding a red-festooned horse

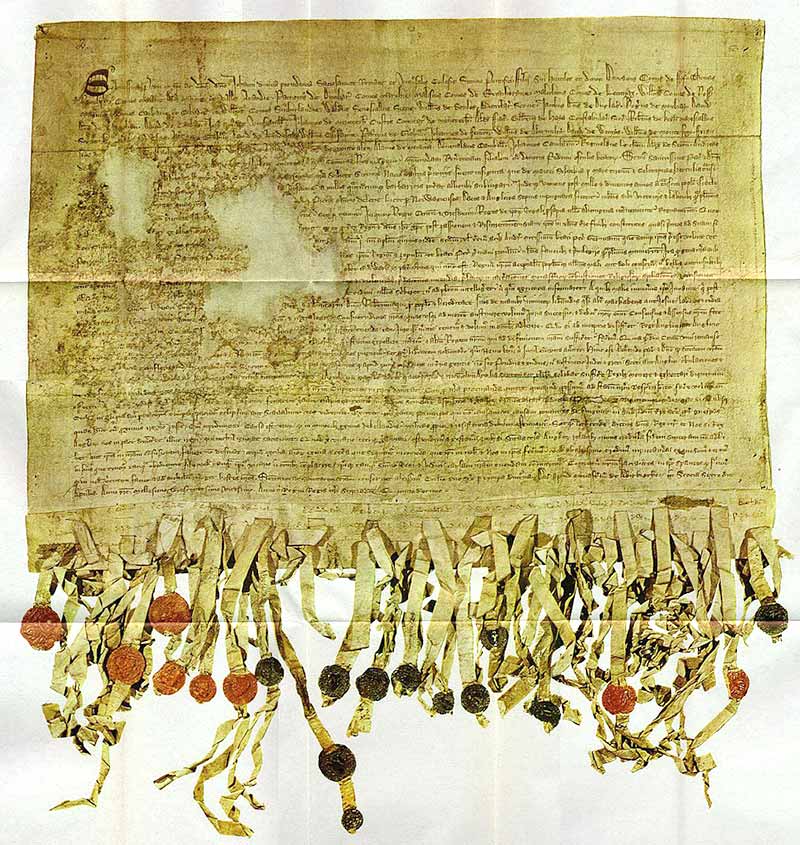

Whether such a happy turn of events saved Isabella’s life in the long run is lost to history. In 1314, after Bruce’s stunning victory over the English at Bannockburn, his female relations were sent home in return for certain English nobles he had captured. Isabella MacDuff is not mentioned in these exchanges, the presumption being she had died before seeing this successful outcome of her daring choice. But the legacy of Clan MacDuff lived on in Bruce’s extraordinary reign, canonized into the fabric of Scottish nationalism with the Declaration of Arbroath signed by the king and his Scottish lords. It declared God as Lord of all and the King of Scots His loyal subject, a willing servant of his under-lords, charged to defend and ensure the liberty of his people.

Statue of Bernard de Linton (then Abbot of Arbroath) and Robert the Bruce holding the Declaration of Arbroath aloft

Reproduction of the “Tyninghame” (1320 A.D) copy of the Declaration of Arbroath

Image Credits: 1 Bust of Robert the Bruce (wikipedia.org) 2 Robert and Isabella (wikipedia.org) 3 MacDuff Castle (wikipedia.org) 4 Death of John Comyn (wikipedia.org) 5 Isabella Crowns Bruce (wikipedia.org) 6 Scottish Independence Heroes (wikipedia.org) 7 Chapel at Moot Hill, Scone (wikipedia.org) 8 Battle of Bannockburn (wikipedia.org) 9 Arbroath Memorial (wikipedia.org) 10 Declaration of Arbroath (wikipedia.org)

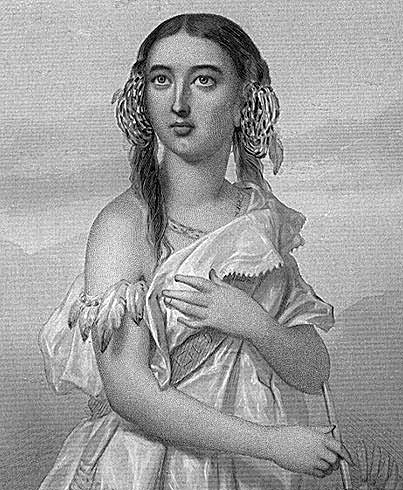

nce upon a time in Jamestown, Virginia, during the days of King James I when America was yet a wilderness, an Indian Princess was traded for a copper kettle. As is often the case with providence, the clumsy schemes of men in the life of Princess Pocahontas resulted in unforeseen blessing and relief for those who had come to establish our country.

nce upon a time in Jamestown, Virginia, during the days of King James I when America was yet a wilderness, an Indian Princess was traded for a copper kettle. As is often the case with providence, the clumsy schemes of men in the life of Princess Pocahontas resulted in unforeseen blessing and relief for those who had come to establish our country.

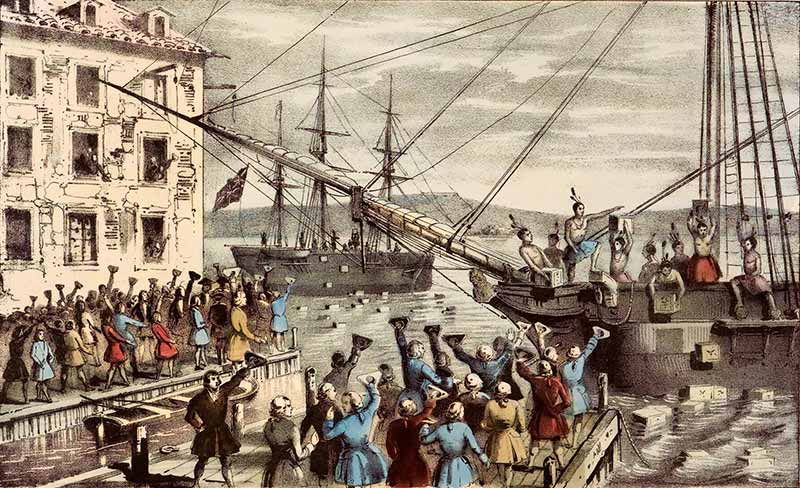

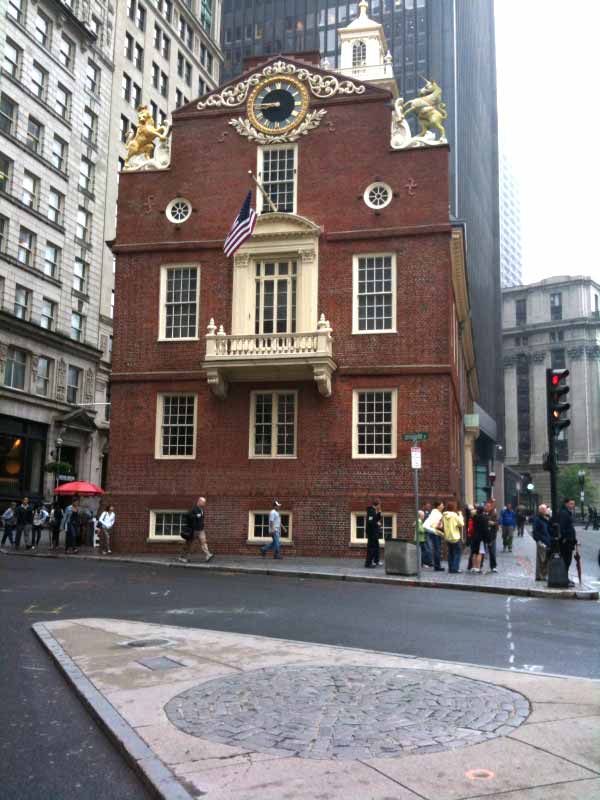

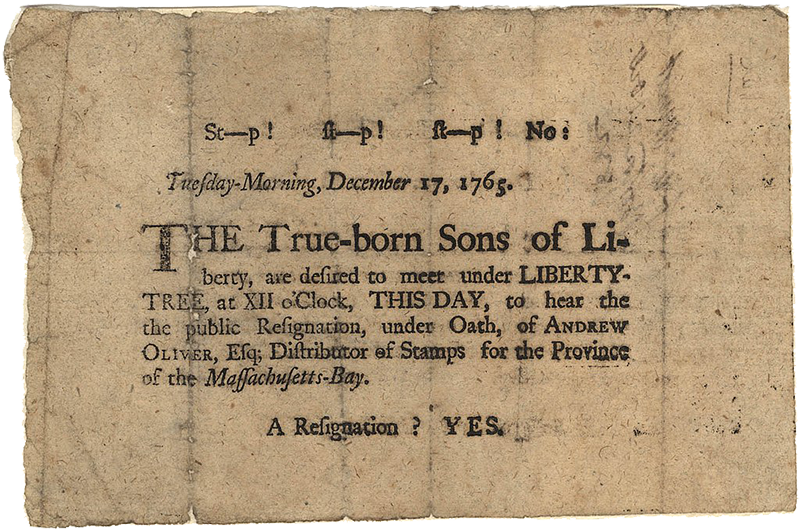

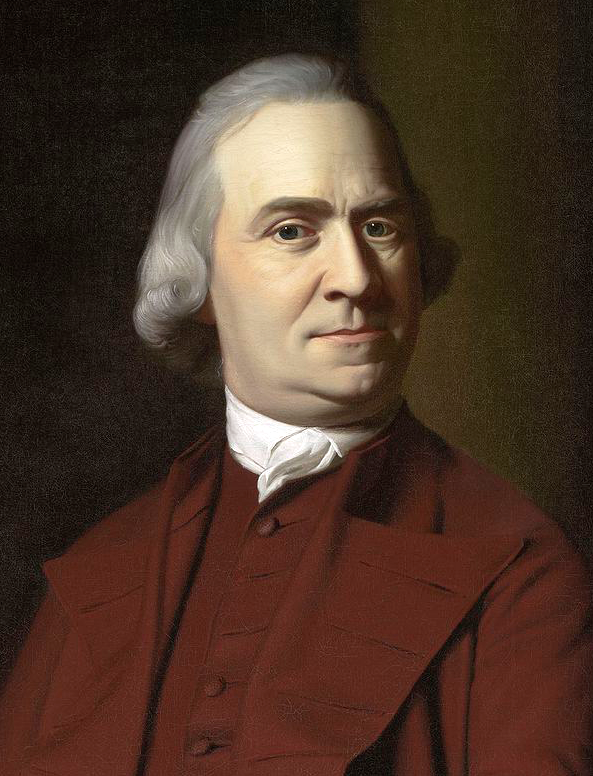

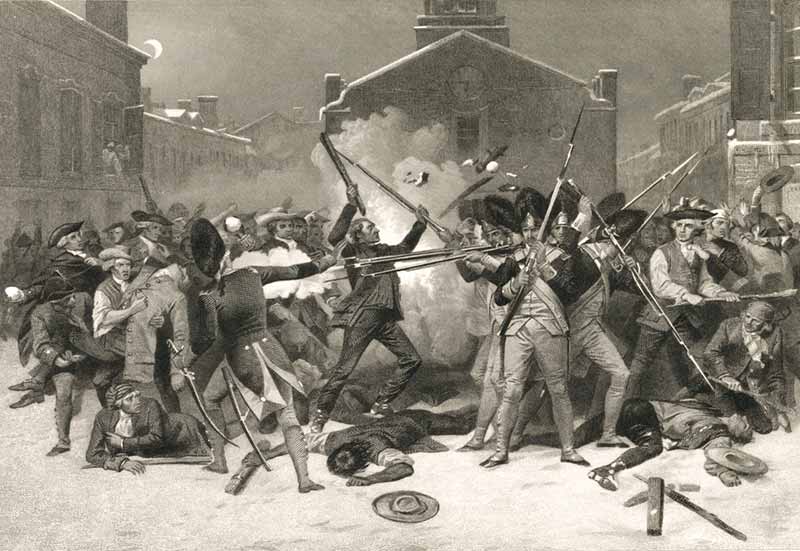

hen looking back at our nation’s road to independence, there were a number of inciting incidents considered to be formative in setting the tone for the manner in which such an unprecedented endeavor would proceed. A string of emotionally-charged battles for the loyalties and conscience of the colonies were engaged in, long before the war of bullets and bayonets.

hen looking back at our nation’s road to independence, there were a number of inciting incidents considered to be formative in setting the tone for the manner in which such an unprecedented endeavor would proceed. A string of emotionally-charged battles for the loyalties and conscience of the colonies were engaged in, long before the war of bullets and bayonets.