“The rich rules over the poor, and the borrower becomes the lender’s slave.” —Proverbs 22:7

Andrew Jackson Vetoes Bank Recharter,

July 5, 1832

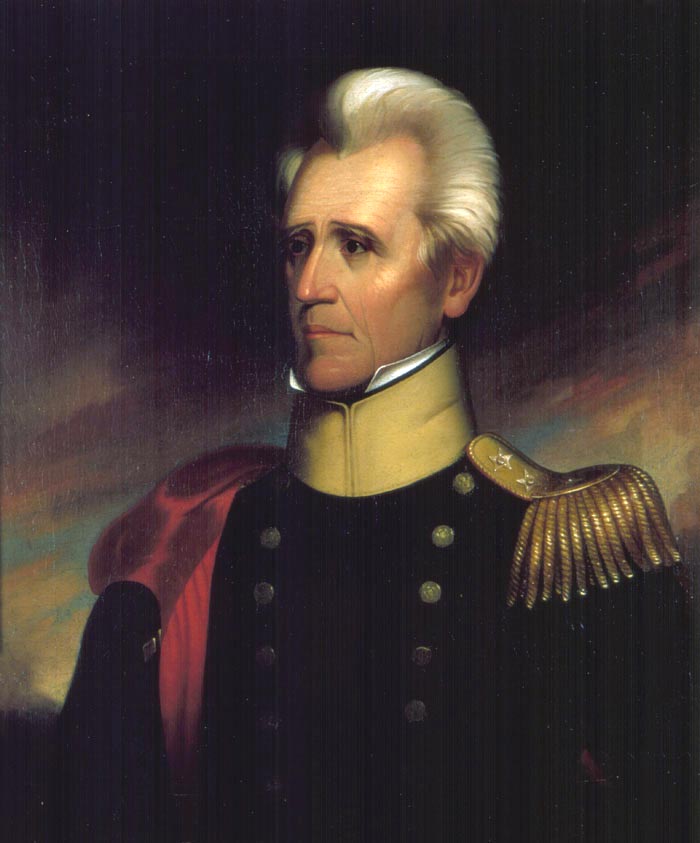

ndrew Jackson, seventh President of the United States, engendered hatred and opposition on a scale that previous chief executives never experienced. Jackson, in fact, still faces hatred and vilification one hundred seventy-three years later. Few people admire him for forcing the Cherokee and Creek tribes to vacate their lands in Georgia, North Carolina and Alabama and move to Oklahoma, though he was applauded for those measures in his own day. He was a slave-owning southerner, like four out of his six predecessors, but he opposed nullification of federal laws by the states, angering many of his original constituents. One of his presidential actions delights libertarians today but produces horror among the government elites, then and now—he vetoed re-chartering the Second National Bank, thus removing the control of the money supply and the economy from the hands of Federal bureaucrats and powerful foreign investors. In the first week of July, 1832 he was presented with the Bank Renewal Bill.

ndrew Jackson, seventh President of the United States, engendered hatred and opposition on a scale that previous chief executives never experienced. Jackson, in fact, still faces hatred and vilification one hundred seventy-three years later. Few people admire him for forcing the Cherokee and Creek tribes to vacate their lands in Georgia, North Carolina and Alabama and move to Oklahoma, though he was applauded for those measures in his own day. He was a slave-owning southerner, like four out of his six predecessors, but he opposed nullification of federal laws by the states, angering many of his original constituents. One of his presidential actions delights libertarians today but produces horror among the government elites, then and now—he vetoed re-chartering the Second National Bank, thus removing the control of the money supply and the economy from the hands of Federal bureaucrats and powerful foreign investors. In the first week of July, 1832 he was presented with the Bank Renewal Bill.

Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), c. 1837

In 1791 Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury, created a financial plan to pay the states’ Revolutionary War debts, mint new money to create a common currency, build a central bank to control the money and establish credit, public and private. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison led the opposition to the Central Bank and the Central government paying the states’ debts. They argued that further centralization of power by the Federal Government away from local banks and state control would primarily aggrandize northern business interests to the detriment of southern farmers, and that such a bank was unconstitutional. George Washington’s support for Hamilton’s plan proved decisive to its success.

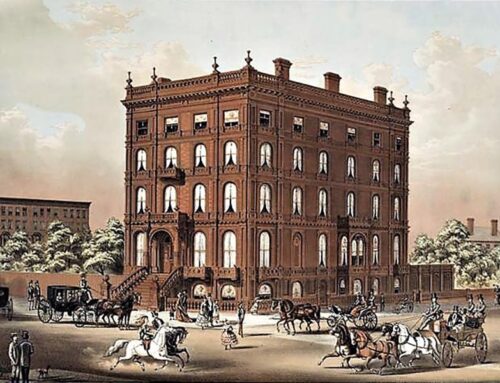

Second Bank of the United States in Philadelphia (built 1818-1824) served as the US Custom House from 1844-1935 after the recharter veto

The Bank of the United States was re-chartered in 1816 by James Madison’s administration, thus becoming the Second Bank of the United States, again headquartered in Philadelphia. Although the next re-authorization of the bank was not due till 1836, the bank president Nicholas Biddle and the leader of the “National Republicans,” a political faction led by Henry Clay and devoted to stopping President Andrew Jackson from reelection in 1832, decided to make the Bank a major political issue four years early. Jackson, who never saw a war he didn’t like, initiated “the Bank War” by vetoing the Bank Bill, thus putting an end to the National Bank. Not content with just stopping the enemies of the “planter, the farmer, the mechanic, and the laborer,” Jackson took measures to remove the deposits from the central bank to give to various state banks, which became known as “Jackson’s Pets.”

Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844)

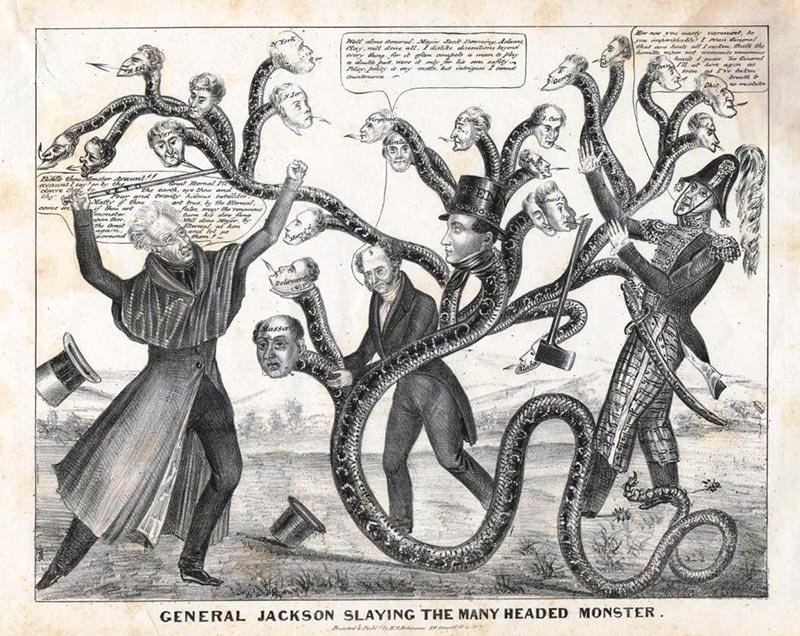

Satirical cartoon showing Jackson’s campaign to destroy the Bank of the United States. Nicholas Biddle is depicted in the middle with a top hat.

Because of what Jackson’s opponents considered his high-handedness, they organized a new political party known as the Whigs, whose main purpose was to defeat “King Andrew I” and all he stood for. Biddle, in an attempt to thwart Jackson, contracted credit, causing an economic downturn. The total dismantling of the Federal government bank, however, went forward until it finally ended in 1841. Jackson had won another war, as he believed, on behalf of the common man against the privileged wealthy northern elites:

“Most of the difficulties our Government now encounters and most of the dangers which impend over our Union have sprung from an abandonment of the legitimate objects of Government by our national legislation. Many of our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits, but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress . . . If we cannot at once, in justice to interests vested under improvident legislation, make our Government what it ought to be, we can at least take a stand against all new grants of monopolies and exclusive privileges, against any prostitution of our Government to the advancement of the few to the expense of the many, and in favor of compromise and gradual reform in our code of laws and system of political economy.” (Excerpt from Andrew Jackson’s veto message)