“And he changeth the times and the seasons: he removeth kings, and setteth up kings: he giveth wisdom unto the wise, and knowledge to them that know understanding.” —Daniel 2:21

The Birth of Robert the Bruce, July 11, 1274

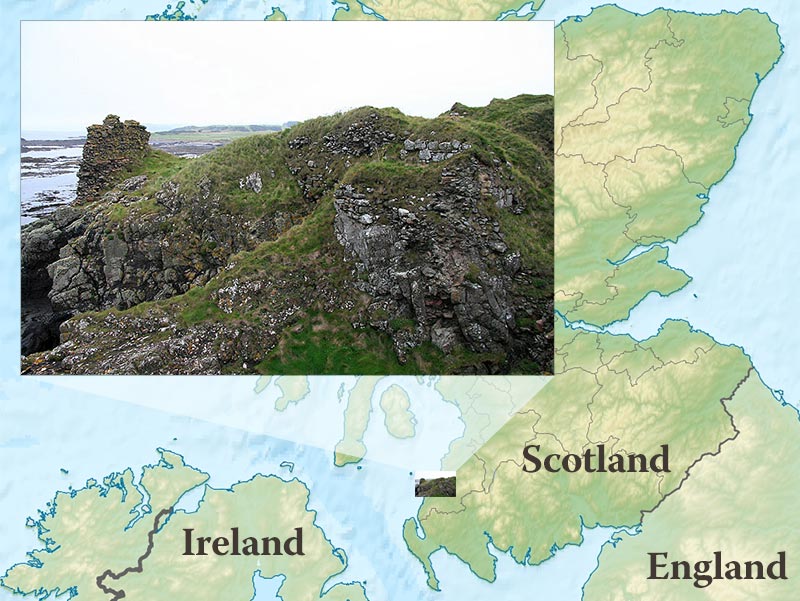

obert Bruce of Scotland was born in 1274, probably at Turnberry Castle, “of which the remains can still be seen perched on the cliffs which plunge steeply into the waters of the firth of Clyde.” His family claimed Anglo-Norman ancestry and served as tenets-in-chief of King David I (c. 1084-1153), who assumed the throne of Scotland from his brother in 1124. The father of Robert the Bruce was the 6th Robert of that name and a warrior who — along with his sixty-year-old father — fought in the Crusades. Robert the Crusader married the widowed Countess of Carrick, who bore him ten children, of whom Robert the Bruce, the 7th of that line, was the oldest son. Genealogies can become tedious very quickly, but when a claimant to the throne must prove his pedigree and be prepared to defend his right to the death, knowing one’s ancestors is of paramount importance. Genealogy is a handmaid of Providence.

obert Bruce of Scotland was born in 1274, probably at Turnberry Castle, “of which the remains can still be seen perched on the cliffs which plunge steeply into the waters of the firth of Clyde.” His family claimed Anglo-Norman ancestry and served as tenets-in-chief of King David I (c. 1084-1153), who assumed the throne of Scotland from his brother in 1124. The father of Robert the Bruce was the 6th Robert of that name and a warrior who — along with his sixty-year-old father — fought in the Crusades. Robert the Crusader married the widowed Countess of Carrick, who bore him ten children, of whom Robert the Bruce, the 7th of that line, was the oldest son. Genealogies can become tedious very quickly, but when a claimant to the throne must prove his pedigree and be prepared to defend his right to the death, knowing one’s ancestors is of paramount importance. Genealogy is a handmaid of Providence.

Ruins of Turnberry Castle, likely birthplace of Robert the Bruce

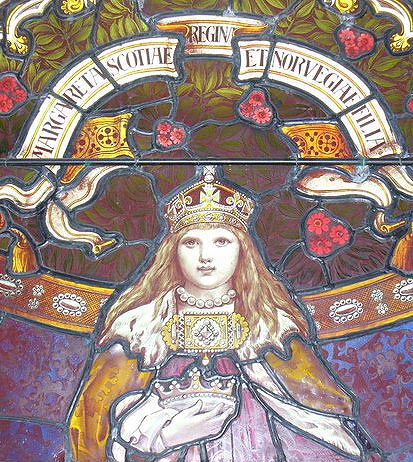

The accession to the throne of Scotland in 1289 depended on Margaret the “maid of Norway,” Alexander III’s seven-year-old granddaughter. King Alexander (1241-1286) had pitched from his horse and broken his neck in the dead of night, travelling home along the shore of Fife after a meeting with his counselors in Edinburgh. The Guardians of Scotland sent for Margaret, but she died of “seasickness” on the way to Scotland. The ambitious and acquisitive King of England, Edward I (1239-1307), who had arranged to marry his own son Edward to Alexander’s granddaughter, stepped in to select the next King of Scotland. Robert de Brus “the Competitor” and thirteen other claimants vied for position but, in 1292, Edward picked John Balliol as next in line to the Scottish throne (for more information on this, see the article Competitors for the Crown of Scotland ).

Margaret, the “maid of Norway” (1283-1290)

King Edward I of England (1239-1307)

Edward treated Scotland as an English vassal and compromised the rule of King John Balliol, who was deposed by the Scottish nobles and replaced with a Council of 12, who promptly made a treaty with France. In response, Edward invaded Scotland in 1296. All through the controversies, the Bruce family remained aloof and loyal to Edward, hoping that the crown of Scotland could still be theirs. When attacked in their castle by rival Scottish forces, the Bruces held fast for Edward. The English King attacked the fortified town of Berwick and killed every man, woman, and child — burying them in a mass grave and replacing them with English families. After conquering Scotland, most of the nobles made their abeyance to Edward who declared Scotland part of England.

John Balliol (c. 1249-1314) and his wife

William Wallace (c. 1270-1305)

The great nobleman North of the Tay, who never pledged obeisance to Edward, Andrew Moray armed his vassals and joined with outlawed William Wallace and his men to defy the English, who brought a Royal army against them. Moray and Wallace defeated them at Stirling Bridge in September of 1297, and the War for Scottish Independence kicked into high gear. Robert the Bruce became a guardian of Scotland with John Comyn, whom he stabbed to death in a church in Dumfries in 1306. He declared himself King of Scotland and was crowned at Scone, the ancient site of the crowning of Kings. He was excommunicated by the Pope, outlawed by Edward, and then driven from his lands by English troops. His wife and daughters were imprisoned in England and his three brothers murdered by Edward. After a brief sojourn in Ireland, Bruce returned to wage a guerrilla war against the English, culminating in a great victory over Edward II at Bannockburn in June, 1314.

As King Robert I, the Bruce served until his death in 1329, fighting more battles with the English, but cementing an alliance with France and securing the Pope’s approval of Scottish independence, for the foreseeable future. An imperfect man who was guided by both pragmatism and principle and who used deception and murder when it suited his purposes, Robert the Bruce never wavered from his goal of securing the independence of Scotland, and the crown, and is still celebrated by some today as Scotland’s greatest hero. How history hinged on the health of a young girl who failed to survive a brief voyage from Norway to Scotland; Providence remains inscrutable.

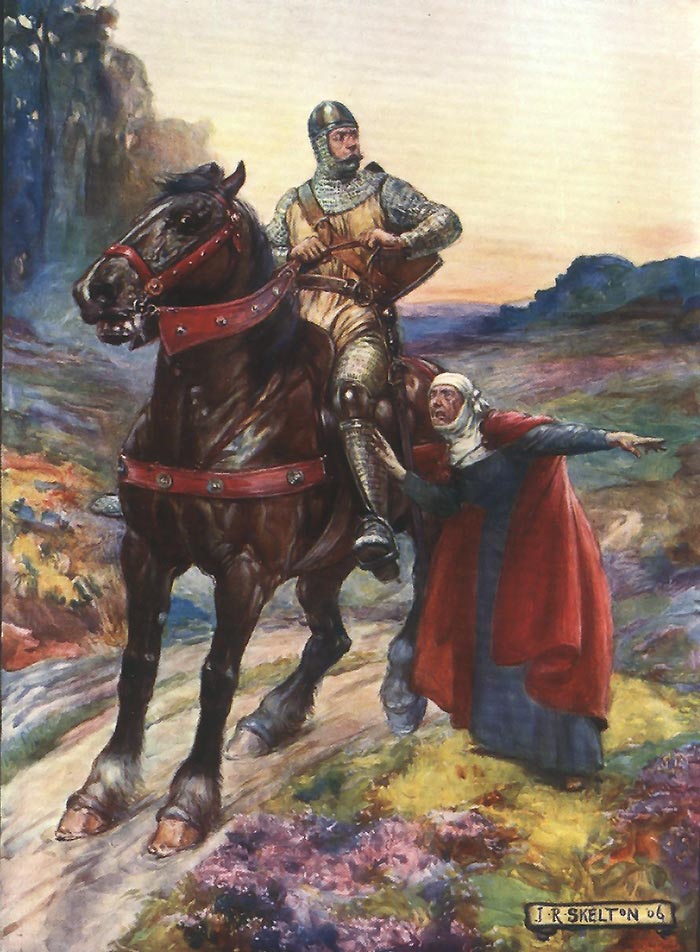

Robert the Bruce (1274-1329) defeats de Bohun on the eve of Bannockburn