“It is He who changes the times and the epochs; He removes kings and establishes kings. . .” —Daniel 2:21

Death of William the Conqueror,

September 9, 1087

![]() cottish writer and historian Thomas Carlyle during the 1840s, and especially in his book Heroes and Hero Worship, argued that history can largely be explained by the actions and leadership of great men of the past. He lauds but a few in his book — Napoleon, Cromwell, Knox, Luther, Rousseau, Shakespeare, etc. but the principle took hold among prominent historians and philosophers. The theory is largely debunked today in favor of economic forces, social factors, or just randomness and chaos. For the Christian, God controls history, and the past should be examined and explained through all the means He uses to further His purposes. I would suggest that that especially includes men of extraordinary ability and leadership. Duke William of Normandy, “The Conqueror”, was one of those men.

cottish writer and historian Thomas Carlyle during the 1840s, and especially in his book Heroes and Hero Worship, argued that history can largely be explained by the actions and leadership of great men of the past. He lauds but a few in his book — Napoleon, Cromwell, Knox, Luther, Rousseau, Shakespeare, etc. but the principle took hold among prominent historians and philosophers. The theory is largely debunked today in favor of economic forces, social factors, or just randomness and chaos. For the Christian, God controls history, and the past should be examined and explained through all the means He uses to further His purposes. I would suggest that that especially includes men of extraordinary ability and leadership. Duke William of Normandy, “The Conqueror”, was one of those men.

William “The Conqueror”, c. 1028 – September 9, 1087

In his time, the 11th century, William’s invasion of England seemed like just another dynastic struggle over who should rule England. With the death in 1066 of the last of the West Saxon kings, Edward the Confessor, three rival claimants to the throne fought to the death for the crown. Harold, the son of the Wessex Earl, Godwin, who had ruled de facto during Edward’s weak reign, was crowned King in Westminster Abbey. Tostig, Harold’s exiled and revengeful half-brother, joined forces with the Norwegian King Harold Hadraga and together they landed a large army in the late summer of 1066 at Stamford Bridge near York. King Harold of England and his own house-carls, of Viking blood themselves, defeated the Norwegians, killing both Hadraga and Tostig.

Battle of Stamford Bridge

In the meantime, William the Conqueror assembled his army and invaded England from Normandy. William’s reputation as a ferocious fighter developed early, since he was the illegitimate son of the Duke of Normandy. The Normans (Norsemen) were Vikings who settled on the coast of France a century earlier and eventually adopted the language and some of the cultural norms of the French, although they carried on constant warfare with them.

Harold raced south two hundred fifty miles to fight William, and they met at Hastings. Toward the end of the battle Harold was shot through the eye with an arrow, and the English were defeated and slaughtered; Duke William of Normandy became King William I of England. The Conqueror marched across England devastating every place that resisted, and building castles to secure his reign, including the Tower of London.

Reenactment of the Battle of Hastings

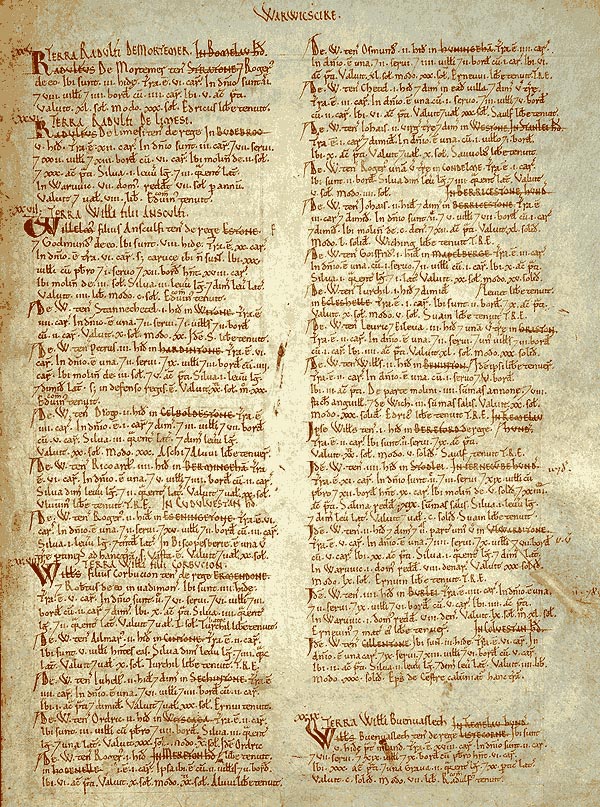

Internal opposition and revolts occurred throughout his kingdom but his knights and their castles kept the island under Norman control. Norman families came with the knights and soldiers to England and thus added another layer of culture to the Danish, Anglo-Saxon, Roman, and Briton heritages already in place. His rule extended into Scotland and Wales through the knightly Norman families. By all accounts William was also a pious churchman, endowing many abbeys and constructing churches. His marriage seems to have been loving and there is no account of unfaithfulness, unusual for men of his stature; his wife bore him ten children. The Domesday Book — his recording of all the land owned in England and by whom — is one of the most important and remarkable documents in English history.

William had to return to France constantly, to put down revolts and invasions of Norman territory, sometimes to fight his own sons. In a battle against the French at Mantes, William’s horse stumbled amidst the burning ashes of the town and somehow the King was desperately wounded by the pommel of his saddle, and perhaps thrown to the ground. He survived in agony at the priory of St. Gervase, at Rouen, for several months, but died from his wound on September 9, 1087, about the age of fifty-nine.

A page from the Domesday Book

Tomb of William “The Conqueror”, Abbaye-aux-Hommes, Caen

God raises up kings and puts them down. His choice of monarchs and the twists and turns they give to history can become the stuff of legends. The more we study them and the more we can understand of their times, may help us better see the effects of sin, redemption, accountability, justice, mercy, and other important matters in our own day. We also can see what God was doing among those of His church in the past. In Normandy, five hundred years later, many thousands embraced the Gospel and the old lands of William the Conqueror became some of the strongest area of the French Protestant Reformation.