“Since the word of the king is authoritative, who will say to him, ‘what are you doing?’” —Ecclesiastes 8:4

Emancipation Proclamation Announced,

September 22, 1862

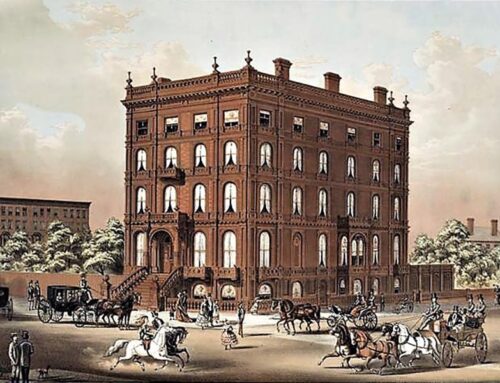

![]() n his First Inaugural Address, President Abraham Lincoln stated that “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” Eighteen months later, September 22, 1862, he issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation that if the “states in rebellion” do not stop fighting and return to the Union, he would declare all the slaves in the Confederacy to be free. The lack of a “lawful right” had not changed, but his inclination obviously had. Why? The slaves behind Union lines in Kentucky, Maryland, many counties in Virginia and parishes in Louisiana would remain enslaved in either case. Again, why? The answers to that complicated situation are interesting and controversial.

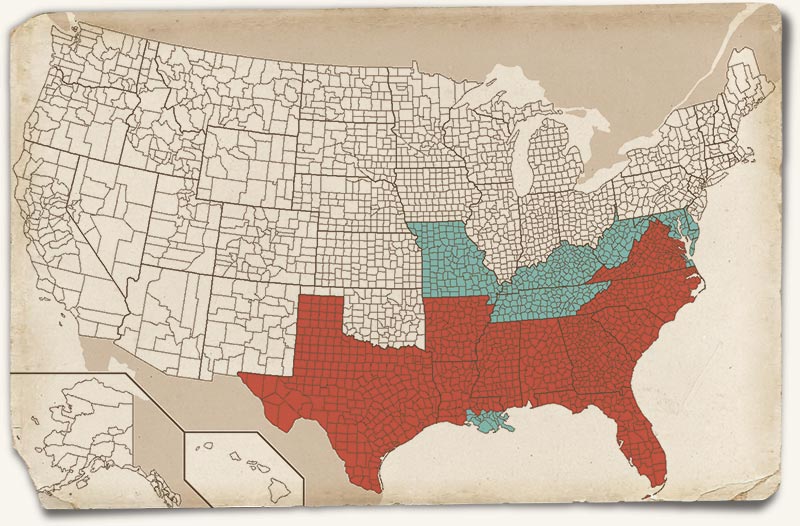

n his First Inaugural Address, President Abraham Lincoln stated that “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” Eighteen months later, September 22, 1862, he issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation that if the “states in rebellion” do not stop fighting and return to the Union, he would declare all the slaves in the Confederacy to be free. The lack of a “lawful right” had not changed, but his inclination obviously had. Why? The slaves behind Union lines in Kentucky, Maryland, many counties in Virginia and parishes in Louisiana would remain enslaved in either case. Again, why? The answers to that complicated situation are interesting and controversial.

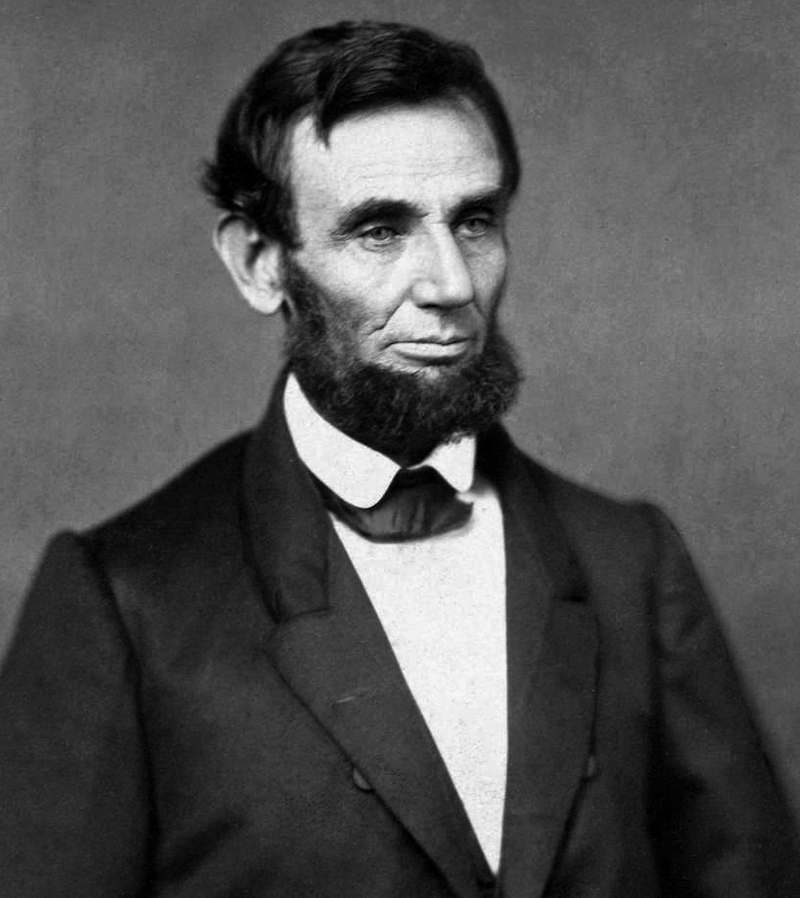

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865)

His first photographic presidential portrait

Crowds gather as Lincoln is sworn in as President at the yet unfinished US Capitol building, March 4, 1861. His First Inaugural Address followed this ceremony.

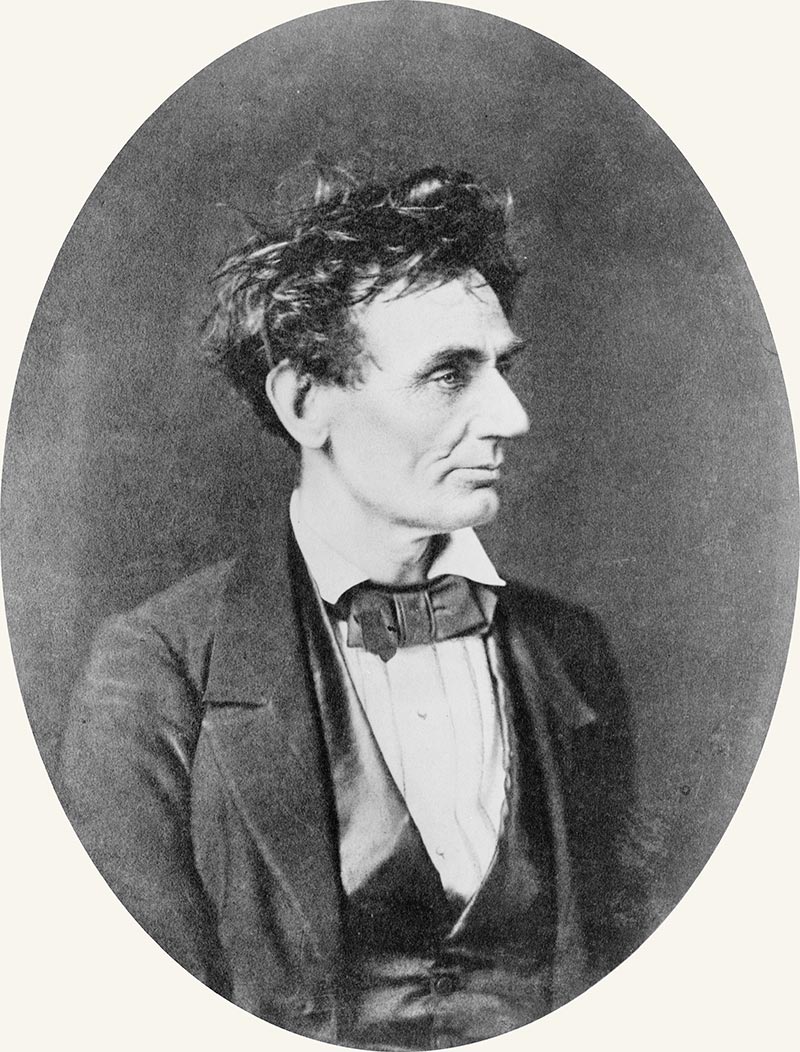

Lincoln in 1857 immediately prior to Senate nomination, Chicago, Illinois

Presumably, had the Confederates stopped fighting and rejoined the Union, there would have been no emancipation. Such an outcome would have been consistent with President Lincoln’s stated purpose for the war — to restore the Union only — and also in line with Republican policy since the Party’s creation in 1854. The issue of slavery for most Republicans focused on keeping slavery in the South and preventing its spreading to the territories. As Abraham Lincoln stated in one of the first addresses for the Party in Peoria, Illinois in 1854, “the whole nation is interested [in whether slavery goes into the new territories]. We want them [the territories] for the homes of free white people. This they cannot be to any considerable extent, if slavery shall be planted with them.” The Party platform of 1860 stated explicitly that they would not interfere with slavery in the southern states. The abolitionists did not like the moderate Lincoln. As a tiny but vocal minority, the abolitionists themselves were execrated by a large portion of the northern people. So what had changed since the election of 1860?

A US map depicting areas covered by the Emancipation Proclamation in red and slave-holding areas not covered in blue

The Union armies in the Eastern Theatre of the war had suffered a string of notable defeats — twice at Manassas, around Richmond in the failed Peninsula Campaign, and elsewhere. Finding a general whose strategic vision matched his own had proven elusive. Both Northern and Southern politicians believed that European powers were considering recognizing the Confederacy as a new nation. Mr. Lincoln — well known as a political pragmatist and under fire from a spectrum of Northern newspapers and politicians — found a way through a declaration of emancipation to theoretically damage the Confederate war effort, leave slaveholders outside Confederate-held territory in possession of their slave property, create a new motivation for fighting the war that might mollify both abolitionists and Britain, yet continue to move his plan ahead to restore the Union. When he floated the idea of the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet in July, some were strongly opposed; Secretary of State Seward suggested he wait till a significant Northern military victory could give credence to the idea that the North could still win the war.

First reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln to his cabinet.

Secretary of State William H. Seward is seated in the foreground, facing Lincoln.

In the famous open letter to newspaper editor Horace Greely of the New York Tribune in August, 1862, Lincoln reiterated his object of fighting the war:

“I would save the Union… the shortest way under the Constitution…. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union and is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it; if I could do it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps save the Union.”

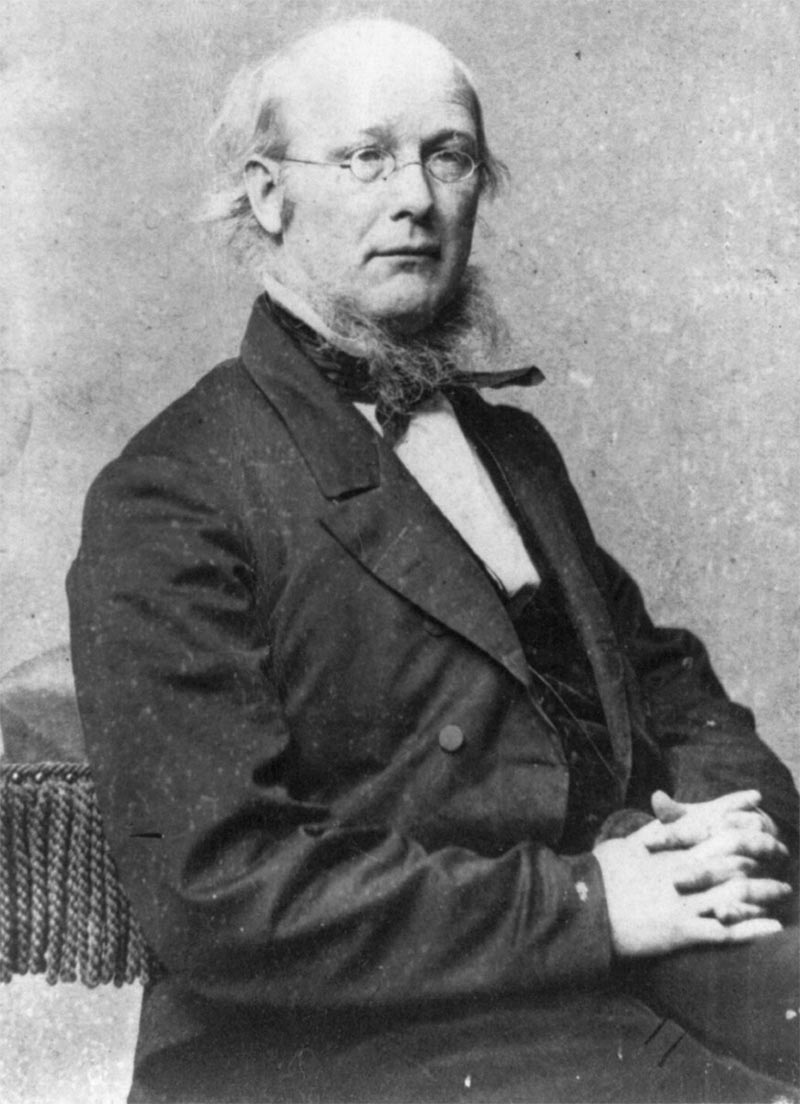

Horace Greeley (1811-1872), founder and editor of the New York Tribune

Upon issuing the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, a firestorm of protest descended on him from constitutionalists, the Northern press and politicians across the Union. Several Northern state legislatures passed laws prohibiting black people from crossing their borders. He responded that the “national emergency” required extraordinary measures and that the natural hostility of the North to slavery could be assuaged with a more activist policy. Indeed, as Lincoln biographer Lord Charnwood pointed out, “The Proclamation had indeed an indirect effect more far-reaching… it committed the North to a course from which there could be no turning back, except by surrender; it made it a political certainty that by one means or another slavery would be ended if the North won.”

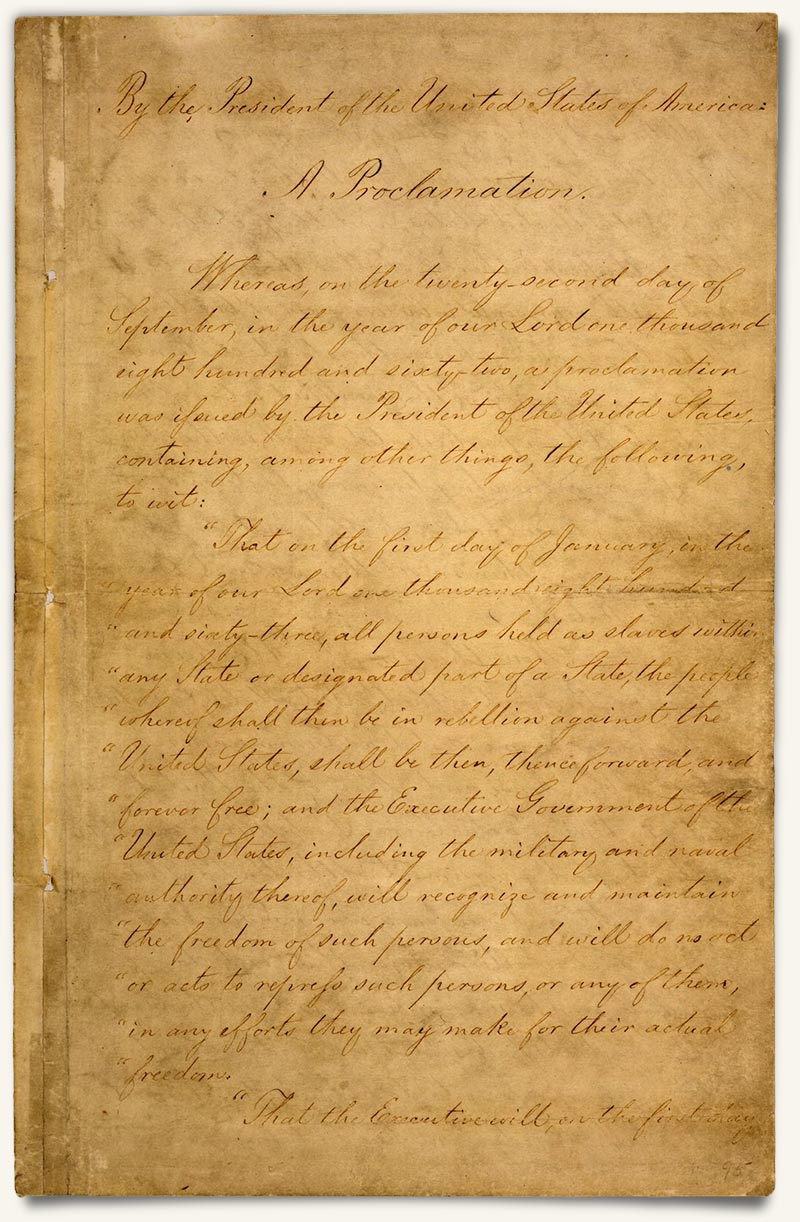

The five-page original document, held in the National Archives Building,

signed September 22, 1862 by Abraham Lincoln

The Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, the bloodiest single day in American military history, gave the President exactly what he was looking for — a Northern victory over Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The fact that the battle was fought on Union soil was icing on the cake, no matter that the battle was a tactical draw; Lee’s retreat to Virginia sealed the announcement of the Proclamation. The announcement did not cripple the South to the extent intended, although almost 200,000 black troops — most of them ex-slaves — enlisted in the Union Army before the war ended. However, it did set the course of the war in a new direction and ended any hopes the Confederacy may have had for British

Confederate dead at Bloody Lane after the Battle of Antietam

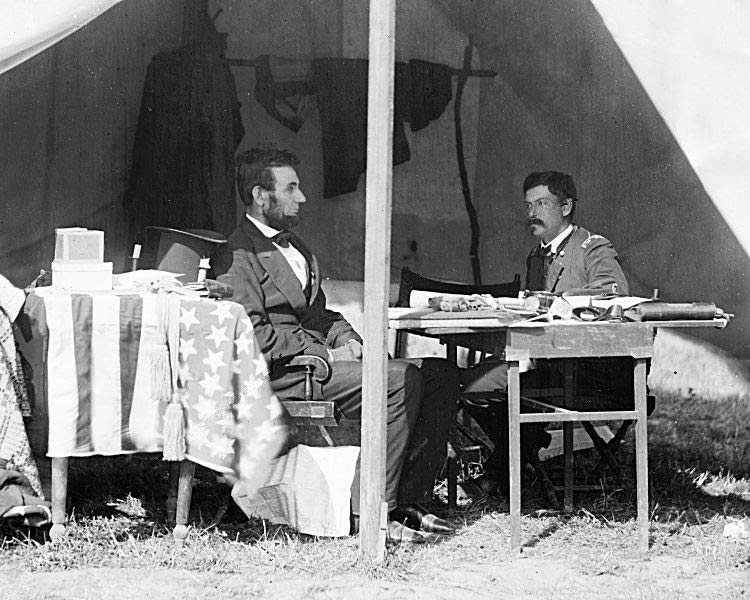

President Lincoln and General George McClellan meet near Antietam Battlefield

Image Credits: 1 Abraham Lincoln (Wikipedia.org) 2 Lincoln inauguration (Wikipedia.org) 3 Lincoln in 1857 (Wikipedia.org) 4 Emancipation map (Wikipedia.org) 5 Cabinet Meeting (Wikipedia.org) 6 Horace Greeley (Wikipedia.org) 7 Emancipation Proclamation (Wikipedia.org) 8 Confederate dead (Wikipedia.org) 9 Lincoln and McClellan (Wikipedia.org)