Republican Party Holds First Convention,

June 17, 1856

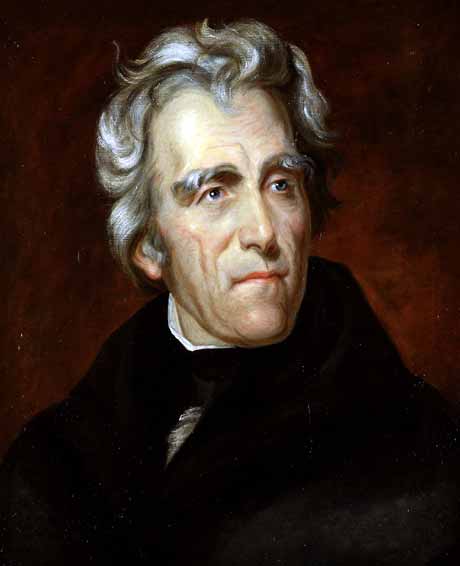

![]() he Presidency of Andrew Jackson changed the direction of American history in significant ways, so much so that his ascendancy has been called “The Age of Jackson” by many historians. His life accords many opportunities to view the Providence of God in action, from his miraculous victory at New Orleans to his survival of numerous duels. Jackson’s controversial political career gave birth to the Whig political party, based on hatred of the Tennessee hero and resistance to his policies. In a very real sense, Jackson is responsible for the two party system, providing a national platform to his opponents, like Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Abraham Lincoln, William Seward and John Quincy Adams. Nine years after Jackson’s death in 1845, the anti-Jackson party, with several other disaffected minor parties, combined to create the Republican Party in Ripon, Wisconsin.

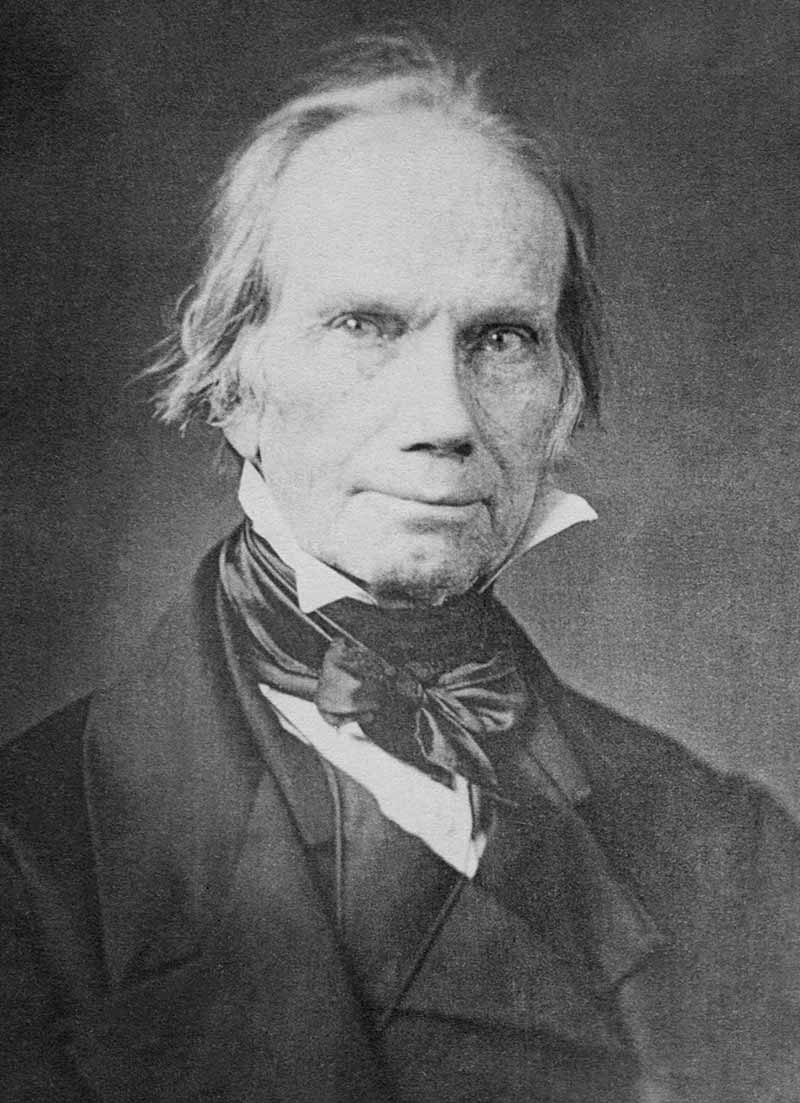

he Presidency of Andrew Jackson changed the direction of American history in significant ways, so much so that his ascendancy has been called “The Age of Jackson” by many historians. His life accords many opportunities to view the Providence of God in action, from his miraculous victory at New Orleans to his survival of numerous duels. Jackson’s controversial political career gave birth to the Whig political party, based on hatred of the Tennessee hero and resistance to his policies. In a very real sense, Jackson is responsible for the two party system, providing a national platform to his opponents, like Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Abraham Lincoln, William Seward and John Quincy Adams. Nine years after Jackson’s death in 1845, the anti-Jackson party, with several other disaffected minor parties, combined to create the Republican Party in Ripon, Wisconsin.

Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) in 1824, the year of his first campaign for President of the United States

Map of the states and territories of the United States as it was from 1850 to March 1853

The Whig vision of the American polity included a high tariff to bolster the central government coffers, so they could finance “infrastructure,” (railroads, canals, bridges, roads etc.), protect the industries of New England, and maintain a strong central banking system. Although unstated publicly, the Whigs hoped to continue the rising political dominance of the Northeast and Midwestern states, downgrading the influence of the Southern states in the national government. Even Southern Whigs would be marginalized if no slave-holding states were created from the territories acquired from Mexico in the War just concluded in 1848. Having failed to prevent Texas statehood, the Whigs were determined to save the newly acquired lands, for white people only.

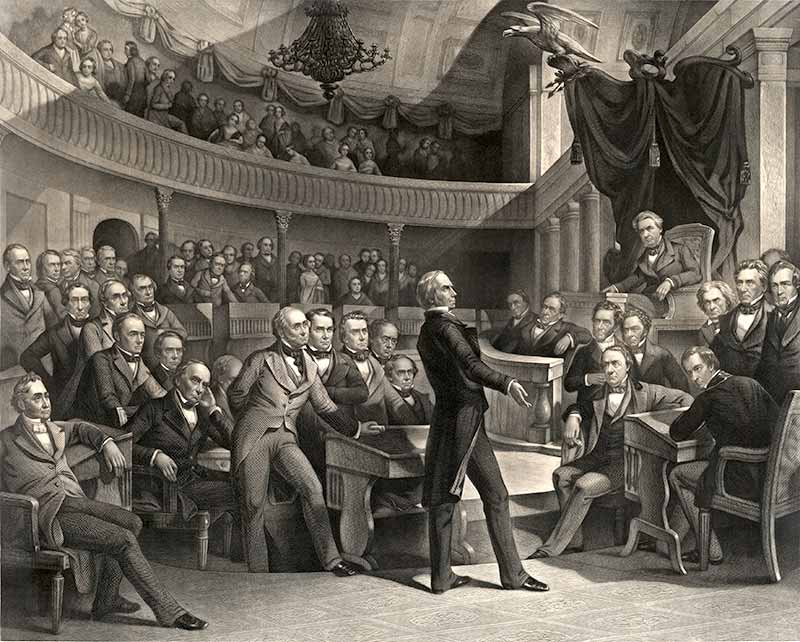

The United States Senate, A.D. 1850: Henry Clay takes the floor of the Old Senate Chamber; Vice President Millard Fillmore presides as John C. Calhoun (to the right of Fillmore’s chair) and Daniel Webster (seated to the left of Clay) look on

The basic core of the Whig (soon to be Republican) Party tended to include professionals, Southern plantation owners, social reformers, middle class entrepreneurs and merchants, and Northern evangelicals. They strongly opposed what they considered executive power overreach, although that issue would be set aside for four years after the first Republican electoral success. They did not take a strong stand on the slavery issue, though they would shortly be conjoined with single-issue political parties and people whose purpose for existence belied the Whig attempt to marginalize the slave issues—the abolitionists and the Free Soil Party, and the anti-immigrationists and the American Party (“Know-nothings”).

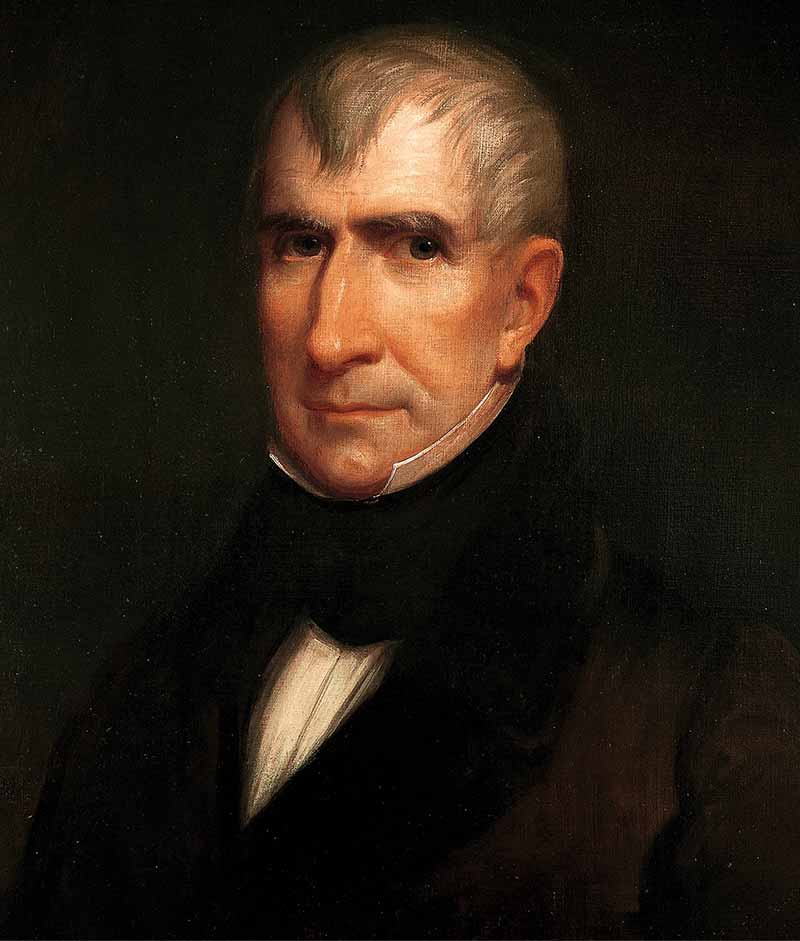

William Henry Harrison (1773-1841), 9th President

Zachary Taylor (1784-1850), 12th President

Whigs had been able to elect two presidents—William Henry Harrison in 1840 and General Zachery Taylor in 1848—but both men died early in office and were replaced with un-Whiggish Vice Presidents. The great leader of the party, Henry Clay, failed to ever get to the White House himself. Two major legislative compromises in 1850 and 1854 became the occasion for the rise of the Republican Party and the demise of the Whigs. The Compromise of 1850 was an omnibus bill combining five others, the most important of which brought California into the Union as a “free state” alienating southern Whigs, and strengthened the Fugitive Slave Laws, further angering northern anti-slavery groups. As Whig support deteriorated over the next four years, the Kansas-Nebraska Bill finished them off. The bill erased the Missouri Compromise of 1820 by turning the slavery issue for a territory becoming a state to the majority vote of the citizens. It triggered a Civil War in Kansas and caused a number of Whig politicians to embrace a new Party, to be known as the Republican Party.

Henry Clay Sr. (1777-1852)

Republican Party Birthplace Museum, Little White Schoolhouse, Blackburn and Blossom Streets, Ripon, Wisconsin

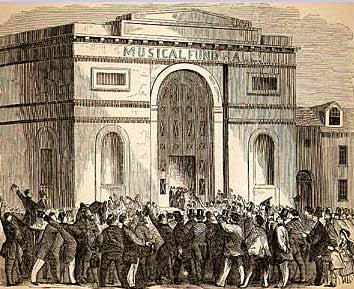

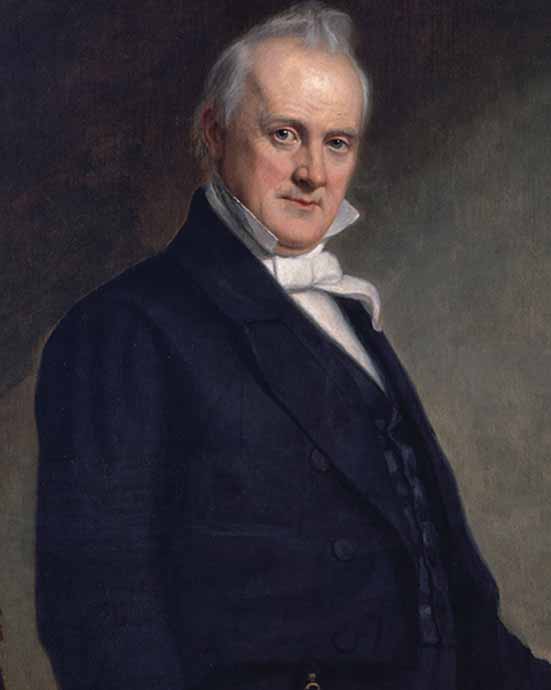

They were joined by Free Soil Party members, most Northern Whigs, former Anti-Masons, anti-slavery members of the American Party and disaffected Northern Democrats. In a shorter than two-year period, the new Party was able to challenge for the Presidency. They held their first meeting in “The Little White Schoolhouse” in Ripon, Wisconsin in March of 1854 in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the idea of popular sovereignty. They also picked apart the anti-immigrant arguments and declared their party for all American voters. On June 17, 1856 they held their first presidential nominating convention in Philadelphia. The National Committee’s determination to keep slavery out of the territories and safely locked in the South, united the new Party as they met to choose their first standard-bearer. They called for congressional sovereignty over the territories and for Federal funding and assistance to build a transcontinental railroad. The delegates—which included only those from Kentucky from below the Mason-Dixon Line—overwhelmingly chose the famous explorer, “The Pathfinder” John C. Fremont of California as the standard-bearer. The Democrats nominated James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, a highly experienced former congressman, senator, Secretary of State, and current Minister to Great Britain, and a strong advocate of States Rights.

A crowd gathers outside the meeting place of the 1856 Republican Convention in Philadelphia

John Charles Frémont (1813-1890), Senator from California, was the Republican candidate for the Presidency in 1856

James Buchanan Jr. (1791-1868)—prominent and experienced politician under multiple Presidents—was the Democratic candidate for the Presidency in 1856, and upon winning the election, 15th President of the United States

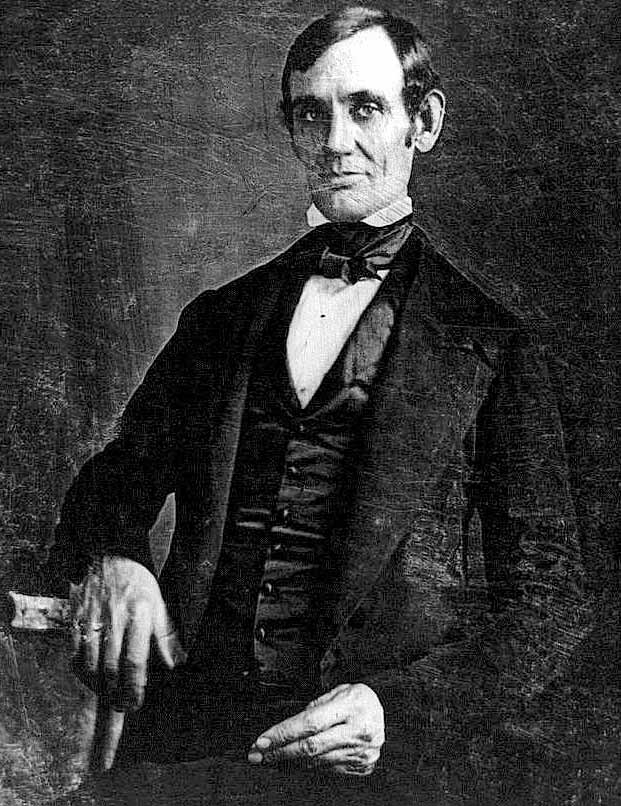

Buchanan won the election, but the new Republican Party garnered 114 electoral votes, more than 33%. It would be the last time Pennsylvania voted Democratic until 1936, and the last time a Democrat won the presidency, with the exception of Grover Cleveland, until 1913. Four years after the 1856 election, the Republicans swept to power with less than 40% of the popular vote, but overwhelmingly in the electoral college. Their candidate was not even on the ballot in the Southern states. The first successful Republican presidential candidate? The old Whig and disciple of Henry Clay, Abraham Lincoln.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) in 1846 as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives

Image Credits: 1 Andrew Jackson (wikipedia.org) 2 1850s Map (wikipedia.org) 3 Senate (wikipedia.org) 4 William Henry Harrison (wikipedia.org) 5 Zachary Taylor (wikipedia.org) 6 Henry Clay (wikipedia.org) 7 Little White Schoolhouse (wikipedia.org) 8 1856 Republican Convention (wikipedia.org) 9 John Charles Frémont (wikipedia.org) 10 James Buchanan (wikipedia.org) 11 Abraham Lincoln (wikipedia.org)