“The wicked accept bribes in secret to pervert the course of justice.” —Proverbs 17:23

The Execution of the Rosenbergs, June 19, 1953

![]() ollowing the Second World War, the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics waged a “Cold War” to bring the “third-world” nations into the political orbit of the West or of the USSR. Both sides were determined to thwart the other, by whatever means. Throughout the 1930s, 40s, and 50s the Russians had subverted Americans sympathetic to international communist goals to spy for them. Communist spies insinuated themselves into Hollywood, the political bureaucracy, the scientific community and industry. They attempted to penetrate the FBI and the CIA. Some of them got caught and went on trial. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg’s trials for espionage and subsequent executions proved to be the most spectacular and controversial of the cold war.

ollowing the Second World War, the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics waged a “Cold War” to bring the “third-world” nations into the political orbit of the West or of the USSR. Both sides were determined to thwart the other, by whatever means. Throughout the 1930s, 40s, and 50s the Russians had subverted Americans sympathetic to international communist goals to spy for them. Communist spies insinuated themselves into Hollywood, the political bureaucracy, the scientific community and industry. They attempted to penetrate the FBI and the CIA. Some of them got caught and went on trial. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg’s trials for espionage and subsequent executions proved to be the most spectacular and controversial of the cold war.

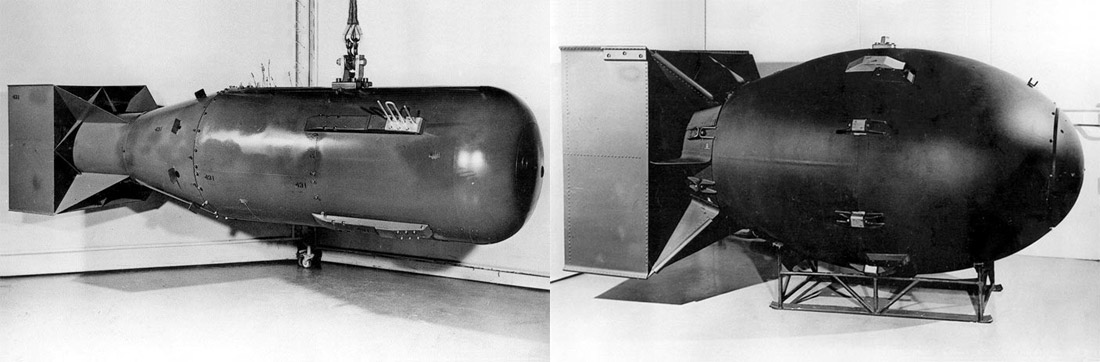

Replicas of the atomic bombs that were detonated over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima Aug 6, 1945 (left) and Nagasaki Aug 9, 1945 (right)

Other than a robust capitalist economy, the United States had one major military advantage over the Soviets — the atomic bomb. Keeping the blueprints for building such a weapon proved impossible when American scientists clandestinely stole the secrets and passed them on to Soviet spies. The Rosenbergs were part of the network of traitors who contributed to Russia’s acquiring the knowledge to build nuclear weapons.

Mushroom cloud from Russia’s first air-dropped atomic bomb test in 1951

Born in New York City in 1918 to a family of Jewish immigrants, Julius Rosenberg formally joined the Communist Party in the 1930s. He was recruited as a Soviet spy in 1942 and, as an electrical engineer for a company making war materials, was able to pass along thousands of classified documents, including the upgraded proximity fuse. Rosenberg’s Russian handler encouraged Julius to recruit more spies, a task at which he proved quite adept, signing up men in strategic industries, from which they passed along all sorts of classified military secrets to the NKVD (Russian secret police). Rosenberg’s foremost recruit proved to be his own brother-in-law, David Greenglass, who worked on the Manhattan Project — the atomic bomb. After the Soviets tested their first nuclear device in 1949, the United States realized that there had to be high-level information leaks in the nuclear program.

Julius Rosenberg (1918-1953)

Ethel Rosenberg née Greenglass (1915-1953)

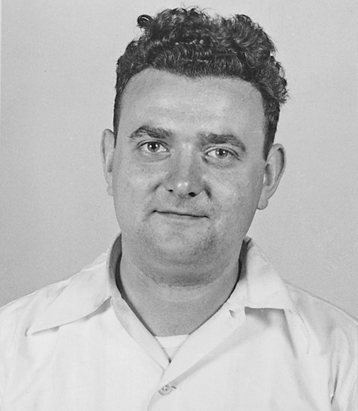

David Greenglass (1922-2014), brother of Ethel Rosenberg

After identifying Klaus Fuchs as a deeply placed spy who passed on secrets of the Manhattan Project all throughout World War II, the FBI began uncovering a whole nest of spies and traitors, including Greenglass. Their confessions and other evidence led to Julius Rosenberg and his wife as the key links in the conspiracy to steal American military secrets. A grand jury settled on eleven counts of espionage against the Rosenbergs and Ethel was arrested and incarcerated to await trial, based on the testimony of her brother and sister-in-law.

German Physicist Klaus Fuchs (1911-1988)

The Rosenbergs refused to “give up” any of their co-conspirators or plead guilty themselves. Julius was accused of passing on the blueprint of an implosion atomic bomb and Ethel of typing up the notes. The couple remained defiant throughout the trial and pled the Fifth Amendment when asked about their involvement with the Communist Party. On March 29, 1951, the Rosenbergs were convicted of espionage and sentenced to death by electrocution. A campaign began immediately to prevent their execution.

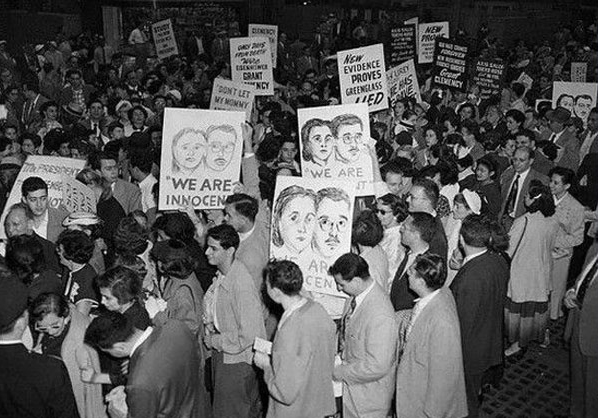

Demonstrators carry signs pleading for clemency for Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Mainstream Jewish organizations refused to come to their aid; even the ACLU claimed no violations had been committed by the prosecution. Others, however, saw the entire episode as a set-up to perpetuate a “red scare” and use the Rosenbergs as scapegoats. The nation was not at war with the Soviets, though they were supporting the North Koreans in that conflict. Prominent Communists and some non-Communists protested long and loud to no avail. President Eisenhower refused amnesty and the Rosenbergs were electrocuted at Sing Sing Prison in New York on June 19, 1953. They were the only two American civilians executed during the cold war. Five hundred people attended their funeral and ten thousand stood outside. The two Rosenberg sons have spent their lifetime trying to get their parents exonerated, or at least their mother. No President has complied. Some scientists estimate that the Rosenbergs and their confederates shortened the Soviet acquisition of the atomic bomb by about one year.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg separated by a wire screen as they leave the U.S. Court House after being found guilty

Espionage can be a dangerous game, but the possibility of executing a spy today in the United States is virtually unthinkable. There are a number of them, however, who have been caught having revealed the names of foreign agents, intelligence “assets,” who were then executed by the Russians or other foreign enemies. Men like Aldrich Ames and Robert Hanson are incarcerated for the rest of their lives.