right understanding of the political importance of taverns in colonial America will help us understand the founding fathers better and give us a keener appreciation for that venerable location (ordinary, tavern, pub, bierstube, or dive) for good food (sometimes), conviviality (usually) and political intrigue (without which, no United States)!

right understanding of the political importance of taverns in colonial America will help us understand the founding fathers better and give us a keener appreciation for that venerable location (ordinary, tavern, pub, bierstube, or dive) for good food (sometimes), conviviality (usually) and political intrigue (without which, no United States)!

Historian Carl Bridenbaugh explained that “the tavern was conceived as a public institution which should provide all needed services, and which should be carefully regulated by law to prevent all usual sorts of abuses.” (Bridenbaugh, p. 114) The ordinary tavern sponsored games and other entertainments as well as provided overnight lodging along with food and drink. In some towns, the courts met in a room at the tavern; in many ordinaries, the merchants conducted their business and shared the latest news from home and abroad. The tavern’s significance in the founding era of our nation related to another main attraction: joining comrades and sometimes opponents in political discourse and debate.

While Boston, Salem, New York, Baltimore and Williamsburg all had their well-known taverns, Philadelphia provided the most establishments for its citizens. William Penn himself believed that taverns would “speed development by serving the needs of workmen and travelers and convincing settlers that Philadelphia was hospitable.” (Struzinski) By 1750 there were one hundred twenty legal taverns in that city alone. While tavern culture was not inherently opposed to civil authority, when the rebellious times came after the French and Indian War, the opportunity and desirability of political discourse increased, and the tavern offered the place for exchanging ideas and mobilizing activists to oppose British tyranny. One of the founding fathers, James Otis, was put upon by British soldiers and severely beaten in a tavern in Boston. In Williamsburg, Virginia, the House of Burgesses retired to the Raleigh tavern to plot their response to the royal Governor. The likes of George Washington, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson and others would reassemble again in Philadelphia as independence loomed, in conjunction with the other twelve colonies.

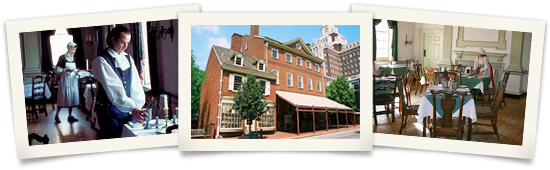

One of the most storied taverns in American history stands at the intersection of Walnut and 2nd Street in Philadelphia. On May 20, 1774 more than two hundred men met in the long gallery there to respond to the request by the patriots of Boston for assistance against the Boston Port Bill, which closed the Port of Boston. By September, the First Continental Congress was meeting in Philadelphia and in another few months, the committees of correspondence, the minute men, and the Patriots of Massachusetts fought the redcoats at Lexington and Concord. The Second Continental Congress began meeting in the summer of 1775 and would draw up the Declaration of Independence. Meeting often in the City Tavern, a place John Adams called “the most genteel tavern in America,” all the founding fathers gathered to discuss liberty, independence, and resistance to tyranny. Please join us July 3 at 7:30pm as we do no less.

You have walked where the Founders walked and have seen what they saw… now eat where they ate, and built a republic over a plate and a glass. Go back in time and discuss how to preserve our Liberty now.

You have walked where the Founders walked and have seen what they saw… now eat where they ate, and built a republic over a plate and a glass. Go back in time and discuss how to preserve our Liberty now.

Gather together with freedom-loving folks for an evening of rejoicing and remembering our nation’s journey to independence in the Historic City Tavern—location of the First Fourth of July Celebration in 1777.

“But a Constitution of Government once changed from Freedom, can never be restored. Liberty, once lost, is lost forever. —John Adams, letter to Abigail Adams, July 17, 1775.

First Course

Corn Chowder

Second Course

Tavern Country Salad

Entrée Choices

Medallions of Beef, Burgundy Mushroom, Demi Glacé

~ or ~

Crab Cake “Chesapeake Style”

~ or ~

Chicken Breast Madeira, Pennsylvania Mushrooms

Dessert

Seasonal Fruit Cobbler, Walnut Streusel