“Now these Jews were more noble than those in Thessalonica; they received the word with all eagerness, examining the Scriptures daily to see if these things were so.” —Acts 17:11

Anselm Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury,

December 4, 1093

![]() cholasticism is the term given to the theology of the Middle Ages (c.500-1500 AD). The Schoolmen “collected, analyzed and systematized” the doctrines of the Church worked out by the post-Apostolic Fathers, and argued their “reasonableness against all conceivable objections.” (Schaff, Vol. V, p. 587) They accepted the authority of the Scriptures but never attempted to discover the best ways to interpret them; they set out to confirm the traditions they had been handed by the Church Fathers and the papacy. The Scholastics made no contributions to exegesis and biblical theology but did pass on the dogmas developed by their predecessors. Most of them were monks, living in cloisters, devoted to God and scholarship. Their ultimate goal was to reconcile dogma and reason and to arrange the doctrines of the Church in an orderly system called summa theologiae. Anselm of Canterbury was the first of the great Scholastics. He was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury on December 4, 1093.

cholasticism is the term given to the theology of the Middle Ages (c.500-1500 AD). The Schoolmen “collected, analyzed and systematized” the doctrines of the Church worked out by the post-Apostolic Fathers, and argued their “reasonableness against all conceivable objections.” (Schaff, Vol. V, p. 587) They accepted the authority of the Scriptures but never attempted to discover the best ways to interpret them; they set out to confirm the traditions they had been handed by the Church Fathers and the papacy. The Scholastics made no contributions to exegesis and biblical theology but did pass on the dogmas developed by their predecessors. Most of them were monks, living in cloisters, devoted to God and scholarship. Their ultimate goal was to reconcile dogma and reason and to arrange the doctrines of the Church in an orderly system called summa theologiae. Anselm of Canterbury was the first of the great Scholastics. He was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury on December 4, 1093.

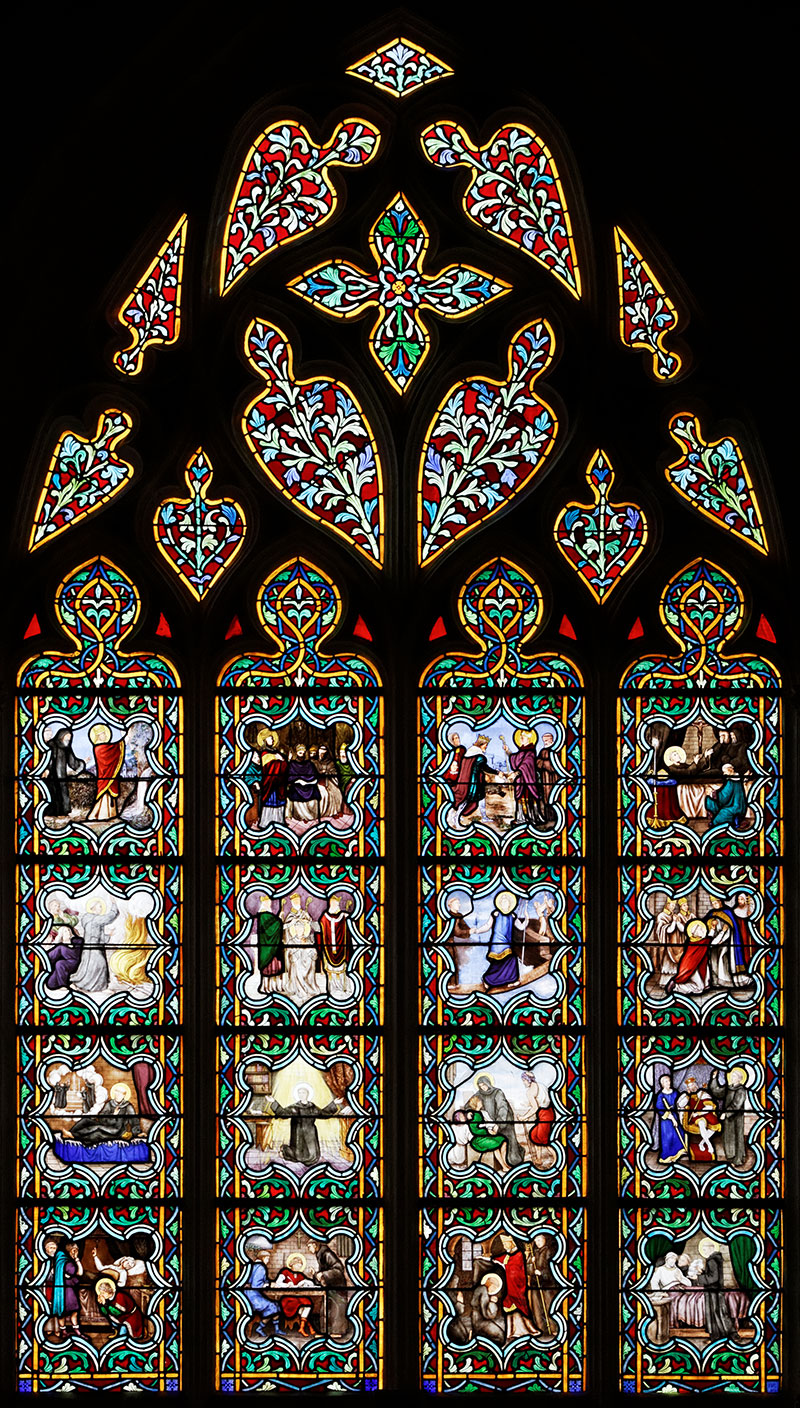

An ailing King William II of England (c. 1056-1100) forces the unwilling Anselm to take the crozier (shepherd’s crook) as a sign of his appointment to the position of

Archbishop of Canterbury

Anselm (1033-1109) began life in Aosta in the region that divides Italy from western Switzerland. He claimed that as a child he conceived that God sat on a throne at the top of the Alps, and in a dream, Anselm climbed up the mountain to meet Him. He was served white bread and treated kindly and, in the morning believed he had actually been to Heaven and back. His father opposed his taking the cowl and leaving for a monastery, but Anselm did so anyway, settling in and taking orders at La Bec in Normandy, France. Anselm wrote most of his works at La Bec and became prior, and in 1078, abbot. He succeeded his friend and mentor Lanfranc as Archbishop of Canterbury in England, where he served until his peaceful death in 1109 at the age of seventy-one. He is venerated by Roman Catholics, Anglicans and Lutherans and respected by other Protestants as well.

The averred birthplace of Anselm in Aosta in what was formerly Upper Burgundy, now part of the Republic of Italy

Bec Abbey, western face—on the left, the old gatehouse and, on the right, the abbey dwelling

His writings were theological, pastoral, and personal, with several major treatises, homilies, meditations, and 412 letters to friends and colleagues. As was evident, “love to God was the soul of his daily life and love to God is the burning center of his theology.” One of his most famous theological aphorisms has been quoted a million times: fides praecedit intellectum—faith precedes knowledge, which churchmen have seen as a harmonization of supernaturalism and rationalism. He was so close in theology to St. Augustine that he has often been called “the second Augustine” and the “tongue of Augustine.” For Anselm, the two sources of knowledge were the Scriptures and the teachings of the Church, which were in perfect agreement, according to Anselm. That belief set the tone for all the other scholastics that followed him.

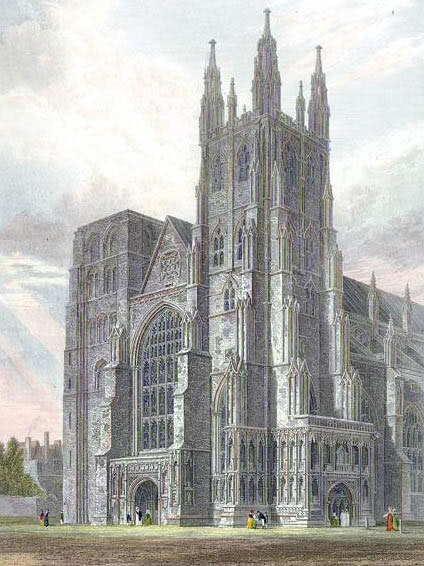

The west front of Canterbury Cathedral in 1821 showing the Norman north west tower prior to rebuilding

Canterbury Cathedral today

On November 29, 1943, the crew of Riki Tiki Tavi flew their fifth bombing mission—target: Bremen, Germany. After dropping their payload, the plane headed for home in England. For some reason, the plane fell behind the fleet—perhaps the engines had been struck by flak or machine gun fire. As the Riki Tiki Tavi fell behind, the German fighter planes pounced, machine guns and cannons firing. In the chaos of the fight, eight of the crew were killed, the navigator successfully bailed out, and Gene was severely wounded in both arms and his parachute shredded. The battle had been fought four miles above the earth so Gene’s arms bled little in the fifty-degrees-below-zero temperature. As he reached for his backup chute, the tail section broke off from the plane and began spinning toward the ground, four miles below, with nineteen-year-old Eugene Moran clinging to the seat. The speed and air pressure popped the gold teeth out of his head and blood pooled in his eyes, obscuring his vision.

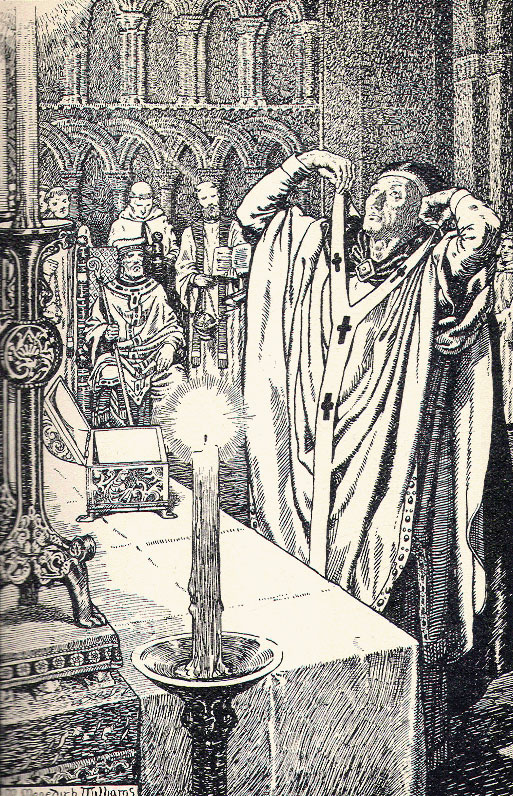

Anselm dons the pallium, a symbol of his position as Archbishop of Canterbury

The meeting of Countess Matilda and Anselm of Canterbury in the presence of Pope Urban II

—Matilda was a staunch and abiding supporter of Anselm

Anselm also set out to prove that Christ’s atonement was necessary using the processes of pure reason. Again, logical argument was the monk’s vehicle to prove that Christ’s satisfaction of justice for sin required the incarnation, crucifixion and resurrection. All sin must either receive punishment or be covered by satisfaction. Can man make this satisfaction? No. Only the God-man could provide atonement. Anselm’s desire was to provide the pagan with no logical way out but through Christ.

The Church historian Phillip Schaff summed up Anselm’s character and contribution to the Church:

“He was the first of the Great schoolmen, was one of the ablest and purist men of the medieval Church. He touched the history of his age at many points. He was an enthusiastic advocate of monasticism. He was archbishop of Canterbury, and fought the battle of the [papal] hierarchy against the State in England. His Christian meditations give him a high rank in the annals of piety. His profound speculations marks one of the leading epochs in the history of theology and won for him a place among the doctors of the Church. . . . He was the most original thinker the Church had seen since the days of Augustine [4th Century].”

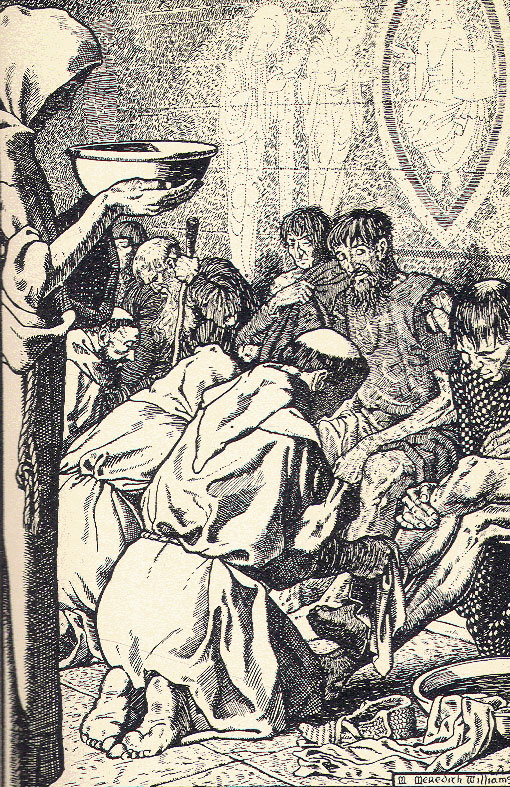

Anselm washes the feet of the poor

The Life of Anselm as told via a stained glass window in his honor, St. Corentin Cathedral in Quimper, Finistère, Brittany, France

Anselm laid the intellectual groundwork for those brilliant Scholastic churchmen who came after, as they systematized dogma and doctrine; the clergy were trained in logic and scholastic argument right up through the Protestant Reformers, who turned to the Scriptures themselves rather than just the early Fathers of the Church and their medieval exponents. After Anselm came Roscellinus, Abelard, Bernard, Hugo de St. Victor, and Gilbert of Poietiers. The second period provided Peter Lombard, Alexander Hales, Albertus Magnus, Bonaventura, Roger Bacon, Duns Scotus, Ockam, and the greatest of them all, Thomas Aquinas. In the fullness of time, by the marvelous Providence of God, they were all superseded by Luther, Calvin, Zwingli, and Knox who loved Augustine and Anselm and appreciated some of those who presented the Scholastic way, but returned to Sola Scriptura to reform the Church.

Anselm of Canterbury (1033/4–1109)

For a good introduction and succinct narrative of the Medieval Church Scholastics, we recommend Volume 5 of Phillip Schaff’s History of the Christian Church.

Image Credits: 1 Anselm receives the crozier (wikipedia.org) 2 Birthplace of Anselm (wikipedia.org) 3 Bec Abbey (wikipedia.org) 4 Norman Canterbury Cathedral (wikipedia.org) 5 Canterbury Cathedral today (wikipedia.org) 6 Anselm dons the pallium (wikipedia.org) 7 Anselm meets Matilda (wikipedia.org) 8 Anselm as a monk (wikipedia.org) 9 Stained glass window (wikipedia.org) 10 Anselm (wikipedia.org)