“Out of whose womb came the ice? and the hoary frost of heaven, who hath gendered it? The waters are hid as with a stone, and the face of the deep is frozen.” —Job 38:29-30

Roald Amundsen Arrives at the South Pole,

December 14, 1911

orwegian explorer Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen lived almost at the other end of the world. He defied the predictions that he would end up a failure or dead, as had all his predecessors in known history, by discovering the South Pole a week and a day before Christmas in 1911. It was a magnificent and almost fatal accomplishment; it made the unsmiling Amundsen the leader of the greatest Polar expedition in history. Cold but alive, Roald and his crew found the most inhospitable spot on planet earth.

orwegian explorer Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen lived almost at the other end of the world. He defied the predictions that he would end up a failure or dead, as had all his predecessors in known history, by discovering the South Pole a week and a day before Christmas in 1911. It was a magnificent and almost fatal accomplishment; it made the unsmiling Amundsen the leader of the greatest Polar expedition in history. Cold but alive, Roald and his crew found the most inhospitable spot on planet earth.

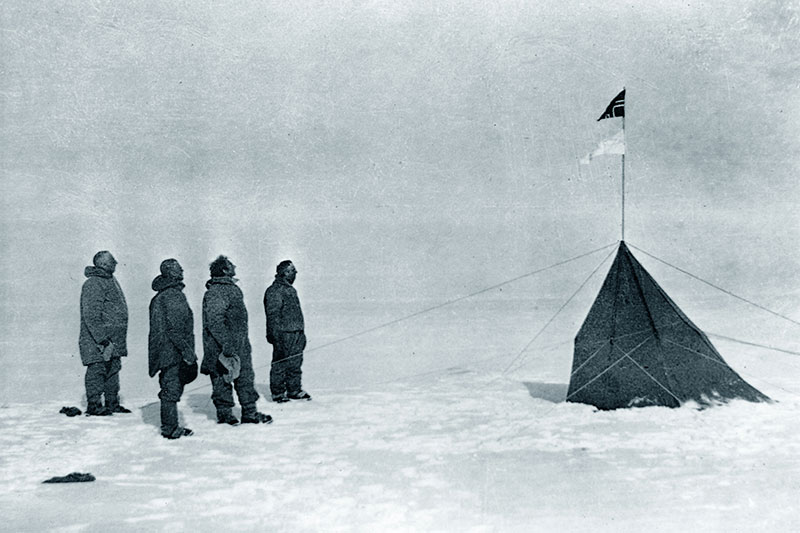

Members of Roald Amundsen’s South Pole expedition 1910-12 at the pole itself, December 1911, (from left to right): Roald Amundsen, Helmer Hanssen, Sverre Hassel and Oscar Wisting

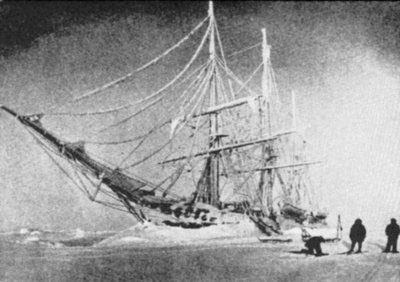

Although his mother did not want Roald, her fourth son, to enter the maritime world of his ancestors, and set him on a medical career, at the age of fifteen he read Sir John Franklin’s accounts of his overland Arctic expeditions, which subsequently, “shaped the whole course of my life.” Books sometimes have a way of defining the rest of a person’s life, especially in their teens. At the age of 25 in 1897 Amundsen joined a Belgian expedition to Antarctica as first mate on the Belgica.

The Belgica during the Antarctic Expedition of 1897-1899

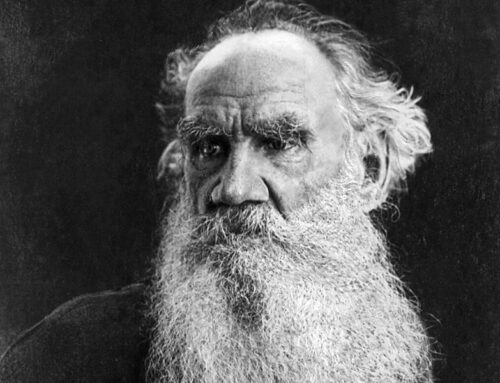

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (1872-1928) in 1906

He learned a great deal from this expedition that would come in handy in future endeavors, especially as they relate to diet and disease. In his first independent exploration command in 1903, Amundsen led the first successful expedition through Canada’s “Northwest Passage,” from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans. From local Inuit tribes he learned Arctic survival skills including wearing animal skins instead of wool in wet weather, and to use sled dogs to transport goods across snow-bound landscapes. Amundsen was one of a number of hard-core explorers determined to get their names in the history books for being the first to accomplish spectacular feats of discovery. Roald secretly planned to lead the way to the discovery of the South Pole. He left Oslo, Norway on June 3, 1910. On the Island of Medeira, he informed his discovery team of their destination—Antarctica—and sent a telegram to his chief competitor, Robert F. Scott, a British naval officer and fellow explorer, also heading for Antarctica in an attempt to get to the South Pole first.

Amundsen in a fur suit and snowshoes

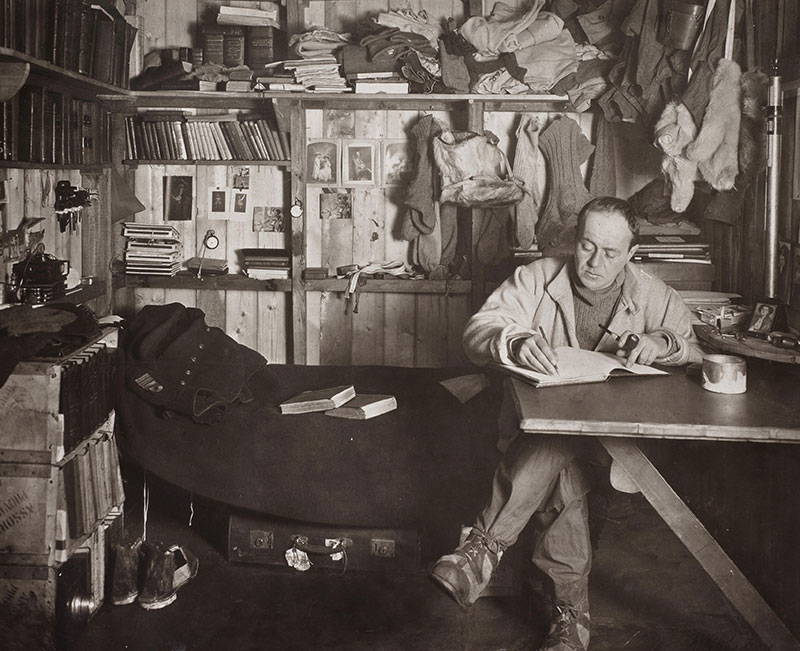

Captain Robert F. Scott journaling in his cabin on October 7, 1911, shortly before setting out on the race to the South Pole

The geographic South Pole is at the southern end of the Earth’s axis, in the Continent of Antarctica, which has no full-time inhabitants or “owners.” The South Pole is approximately 300 miles South of the Ross Ice Shelf at about 9,300 feet above sea level, though it is constantly changing in the 8,850 foot thick ice sheet. Like its opposite pole, the South Pole is in darkness six months of the year and bright sunlight six months. The continent of Antarctica is 5.275 million square miles.

The respective routes of the Scott and Amundsen expeditions

Amundsen had twenty men, all good skiers, and fifty-two sled dogs aboard the Fram. Scott took about sixty men, along with ponies, dogs, and sleds in his ship the Terra Nova. They began the hunt for the South Pole from the Bay of Whales and Camp Evens respectively. Amundsen prepared very carefully for the trek—mistakes in Antarctica could prove fatal very quickly. He positioned food caches along his route ahead of time to be sure he had supplies coming and going. On October 19, 1911, Roald Amundsen set out across the ice sheets and mountains of Antarctica with four of his men and the dogs; Scott and his men left on November 1 with the ponies, on a longer but safer route than that taken by Amundsen.

Amundsen’s South Pole party, en route to the pole, November, 1911

Braving the bottomless crevasses, mountains of ice, and temperatures that are much lower than the North Pole’s, the many pieces of knowledge Amundsen had acquired in previous expeditions came together to enable him to survive the trek to the Pole, arriving there on December 14. He planted the Norwegian flag and left a note for Captain Scott. The English Captain reached the South Pole on January 17, with four of his men. They had been forced to eat the ponies, and travelled many miles further than his Norwegian rival. The extreme cold killed two of his four companions on the return trip, and Scott himself with his fourth man got caught in a blizzard with high winds, and they both also perished.

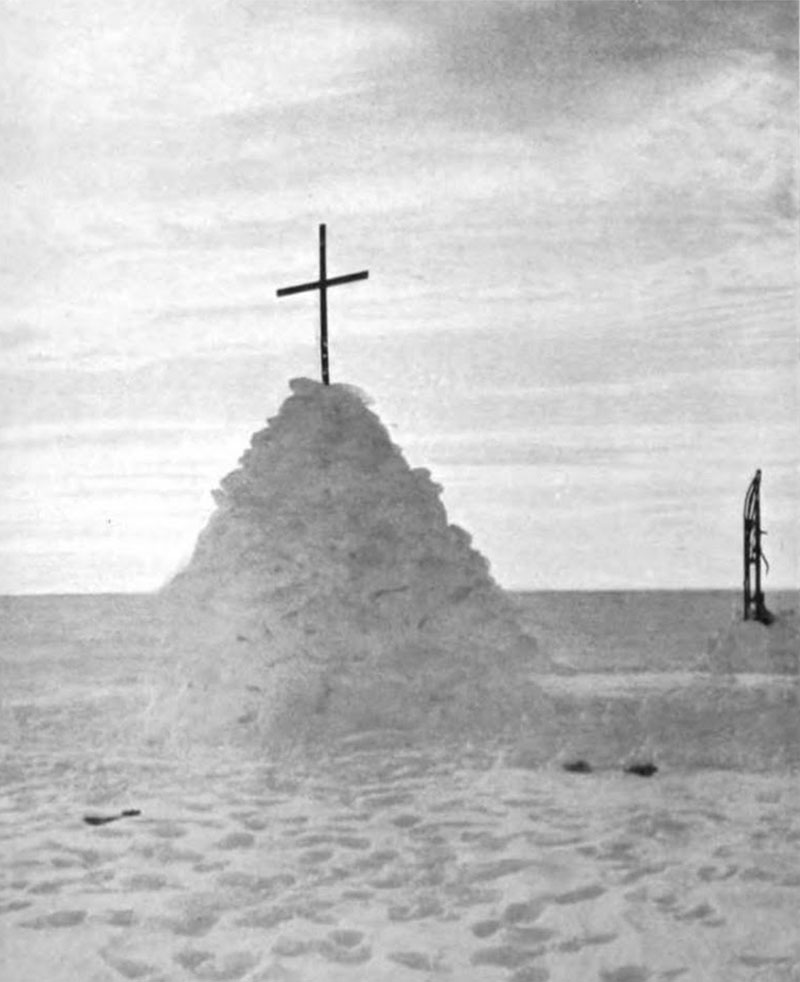

Cairn over the tent containing the bodies of Scott, Wilson, and Bowers

The crew of Scott’s ill-fated South Pole expedition at the Pole, from left to right: Oates (standing), Bowers (sitting), Scott (standing in front of Union Jack flag on pole), Wilson (sitting), Evans (standing), photo by Bowers who took this photograph using a piece of string to operate the camera shutter.

Roald Amundsen became the toast of the world of explorers and the subject of front page news around the world. With the fame and popularity came enough money to start his own shipping business. His book entitled The South Pole proved a commercial success. In 1928 Amundsen died at the age of fifty-six, when his plane went down over the ocean on the way to rescue a friend whose derigible had crashed, but his reputation was secure as the man who first found the South Pole. The United States built a station on the South Pole, with an airstrip known internationally as Amundsen-Scott. The quest for adventure and discovery has moved from earth to space. Who will be the first man to land on Mars?

Amundsen and Hanssen at the South Pole, marked by their Norwegian Flag

Image Credits: 1 Amundsen Expedition at the Pole (wikipedia.org) 2 Belgica in ice (wikipedia.org) 3 Amundsen in 1906 (wikipedia.org) 4 Fur suit (wikipedia.org) 5 Scott journaling (wikipedia.org) 6 Routes (wikipedia.org) 7 Amundsen party (wikipedia.org) 8 Scott party graves (wikipedia.org) 9 Scott Expedition (wikipedia.org) 10 Amundsen & Hanssen (wikipedia.org)