“Man proposes, but God disposes.” —Isaiah 46:9,10 (paraphrase)

Defeat of the Spanish Armada, August 8, 1588

dults and children alike complain that history teachers force students to memorize dates and the events therein associated, which “just turn the pupils away from learning history.” They assume such data is boring and irrelevant. Nonetheless, dates and timelines help pin those important past events to their era and help bring understanding to the flow and consequences of providence, as it relates to interpreting the past. In western European history, the year 1588 stands out as a hugely significant year; the Battle of Gravelines on August 8 insured the destruction of the Spanish Armada.

dults and children alike complain that history teachers force students to memorize dates and the events therein associated, which “just turn the pupils away from learning history.” They assume such data is boring and irrelevant. Nonetheless, dates and timelines help pin those important past events to their era and help bring understanding to the flow and consequences of providence, as it relates to interpreting the past. In western European history, the year 1588 stands out as a hugely significant year; the Battle of Gravelines on August 8 insured the destruction of the Spanish Armada.

English Ships and the Spanish Armada, August 1588

By the middle of the 16th Century, Habsburg Spain had established a global empire and created the only major standing army in Europe. While the Iberians conquered South America, Portugal, and the Caribbean, and consolidated their claims to the Philippines and other stations in the Far East, his “most Catholic Majesty,” King Philip II sent armies to punish and secure his claims to the Netherlands.

Philip II of Spain (1527-1598)

England had fought three wars with France under Henry VIII and had broken with the Papal Church, proclaiming the English King as the head of the Church. Upon Henry’s death and the elevation to the throne of the decidedly Protestant King Edward VI, who ruled from age 9-15, Protestantism was firmly entrenched in English society. Upon his premature death, Edward’s Roman Catholic half-sister Mary Tudor ascended the throne. She attempted to roll back the Protestant Reformation, with the support of the King of Spain, who married her in 1556. Mary sent English forces on a Spanish-inspired, ill-advised military campaign against France, at which time the French seized the Port of Calais, which had been an English enclave for five hundred years. With the death of Mary in 1558 (alas, another date!), Elizabeth became Queen of England and, although not an inveterate enemy of Spain, secretly supported her sea-dogs, like Francis Drake, preying on the Spanish treasure ships, for a share of the loot. The stage was set for Spanish reprisal against England.

Queen Mary I of England (1516-1558)

Queen Elizebeth I of England (1533-1603)

Philip worked secretly to put Mary Queen of Scots on the throne, which in the end, got her beheaded for treason. The Spanish ambassadors worked assiduously to get Queen Elizabeth to embrace Spain’s view of the world and take actions against English pirates, all to no avail. Beginning in 1583, Philip began entertaining the possibility of invading England, after Elizabeth supported the Dutch revolt against Spain and funded more piratical enterprises against Spain’s treasure fleets. Pope Sixtus V signaled his approval of an invasion of England to overthrow Elizabeth, and re-establish the True Faith. Plans got underway to build a fleet of powerful warships to destroy English privateers and to land a Spanish army on the shores of Britain.

Pope Sixtus V (1521-1590)

Álvaro de Bazán y Guzmán, 1st Marquis of Santa Cruz (1526-588)

Alonso Pérez de Guzmán y de Zúñiga-Sotomayor, 7th Duke of Medina Sidonia (1550-1615)

Philip chose the veteran warrior Marquis of Santa Cruz to lead the Armada. He died in February of 1588 and was replaced by a man with no naval experience, Medina Sidonia. The pope sent crusade money and indulgences for all the sailors and soldiers embarking on the expedition. Although Medina Sidonia expressed doubts about the enterprise, he was assured that God guaranteed success and Spain completed the Armada. Spain sailed 141 ships with 2,500 guns, and almost 10,000 sailors and 20,000 infantry for the shores of England. 30,000 more soldiers were mustered in the Netherlands for the invasion.

Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596)

Sir John Hawkins (1532-1595)

One hundred twenty-two ships managed to reach the English Channel and they were met by 226 English ships, only 34 of which were part of the “Royal Fleet.” Many of the rest were privateers, led by Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Hawkins. The English ships were lighter and faster but out-gunned two to one by the lumbering wooden castles, deemed by the captains and Spanish dons, invincible!

The basic tactics of the Spanish naval engagement called for a round of artillery fire, close the gap with the enemy, and board their ships with marines and soldiers to overwhelm them in hand-to-hand combat. In order to prevent boarding, the English ships, much quicker and lighter, would pound the enemy with artillery and keep moving, hoping to hole the big ships below the waterline and cause as many casualties as possible by raking the decks with cannon fire.

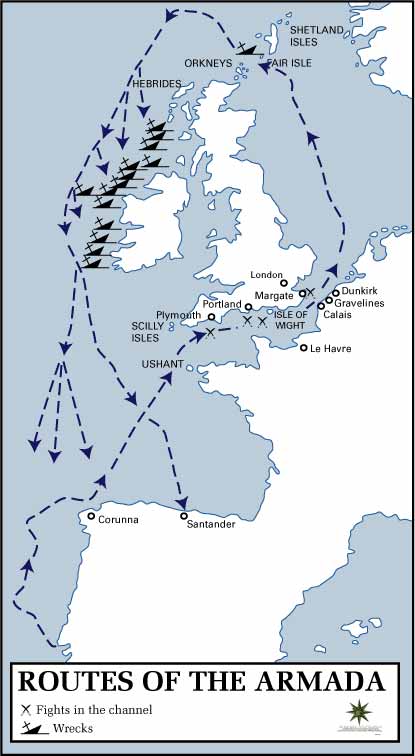

Route of the Spanish Armada

English fireships terrorize the Spanish Armada

The English sighted the Spanish fleet off Plymouth on July 29. As the tide turned, fifty-five English ships emerged from the harbor and engaged the Armada for the first time on July 31, avoiding close-quarters combat, neither side losing a ship. They re-engaged on August 1 off Portland, this time the Spanish losing several ships in accidental collisions and two captured. On August 1, the Armada anchored off Calais in a tight formation, expecting the Spanish army of Flanders to join them there. In the middle of the night of August 6 to 7, the English set alight eight fire-ships filled with pitch, tar, gunpowder, and brimstone, and turned them loose among the closely packed Armada. Most of the fleet cut their anchors and scattered. With the Armada out of fighting formation, the English attacked the next day off Gravelines.

The Surrender of Pedro de Valdés to Francis Drake aboard Revenge during the attack of the Spanish Armada, 1588

Closing to within one hundred yards of their prey, the English cannon pounded the lumbering galleons. The cannon on the Spanish decks were too close together, with ammunition packed in too close between the artillery, hampering the effectiveness of the Spanish rate of fire. Drake’s ships provoked Spanish fire but stayed out of range of boarding and fired broadsides into the Armada vessels, causing horrific casualties on some, and sinking others. Both sides were close enough for musket fire from the rigging. After eight hours, the English began to run out of ammunition and withdrew. Five Spanish and Portuguese ships sank and others ran aground, a few on the shoreline where they were set upon by Dutch and English soldiers.

A ship of the Spanish Armada lies wrecked off the coast

The next day the remainder of the Armada sailed north around Scotland and Ireland, a number of ships sinking in storms or from the battle damage. Spanish sailors who survived were usually killed by the Scots or the Irish, depending on where they happened to come ashore—too many providential circumstances arrayed against the Armada that even the Pope couldn’t overcome them . . .

Image Credits: 1 Spanish Armada (wikipedia.org) 2 Philip II of Spain (wikipedia.org) 3 Queen Mary of England (wikipedia.org) 4 Queen Elizabeth I of England (wikipedia.org) 5 Pope Sixtus V (wikipedia.org) 6 Marquis of Santa Cruz (wikipedia.org) 7 Duke of Medina Sidonia (wikipedia.org) 8 Sir Francis Drake (wikipedia.org) 9 Sir John Hawkins (wikipedia.org) 10 Route of the Spanish Armada (wikipedia.org) 11 Fireships (wikipedia.org) 12 Surrender (wikipedia.org) 13 Wreck (wikipedia.org)