“And ye shall hear of wars and rumors of wars: see that ye be not troubled: for all these things must come to pass, but the end is not yet. For nation shall rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom: and there shall be famines, and pestilences, and earthquakes, in many places.” —Matthew 24: 6,7

Great Britain Grants India and Pakistan Independence, August 13 & 14, 1947

![]() he Mughal Empire ruled most of the Indian subcontinent, Afghanistan, and modern Pakistan and Bangladesh for about 200 years. In the 18th Century, Great Britain established hegemony over much of that Empire beginning in 1747, administered through the East India Company and its loyal Indian satraps known as rajahs. The Raj, or “Hindustan”, as the English typically called India, was also viewed as “the Crown Jewel” of the British Empire. A few thousand dedicated and competent British civil servants backed by the soldiers of the Company and, after 1858, several brigades of the Army, successfully administered the authority over millions of Indians for about 200 years. On August 13 and 14, 1947, Great Britain granted independence to India and Pakistan, leaving the mortal enemies, Moslems and Hindus, to fend for themselves. Chaos and massacre occurred throughout the former Raj, as predicted by the old India hands in the British government.

he Mughal Empire ruled most of the Indian subcontinent, Afghanistan, and modern Pakistan and Bangladesh for about 200 years. In the 18th Century, Great Britain established hegemony over much of that Empire beginning in 1747, administered through the East India Company and its loyal Indian satraps known as rajahs. The Raj, or “Hindustan”, as the English typically called India, was also viewed as “the Crown Jewel” of the British Empire. A few thousand dedicated and competent British civil servants backed by the soldiers of the Company and, after 1858, several brigades of the Army, successfully administered the authority over millions of Indians for about 200 years. On August 13 and 14, 1947, Great Britain granted independence to India and Pakistan, leaving the mortal enemies, Moslems and Hindus, to fend for themselves. Chaos and massacre occurred throughout the former Raj, as predicted by the old India hands in the British government.

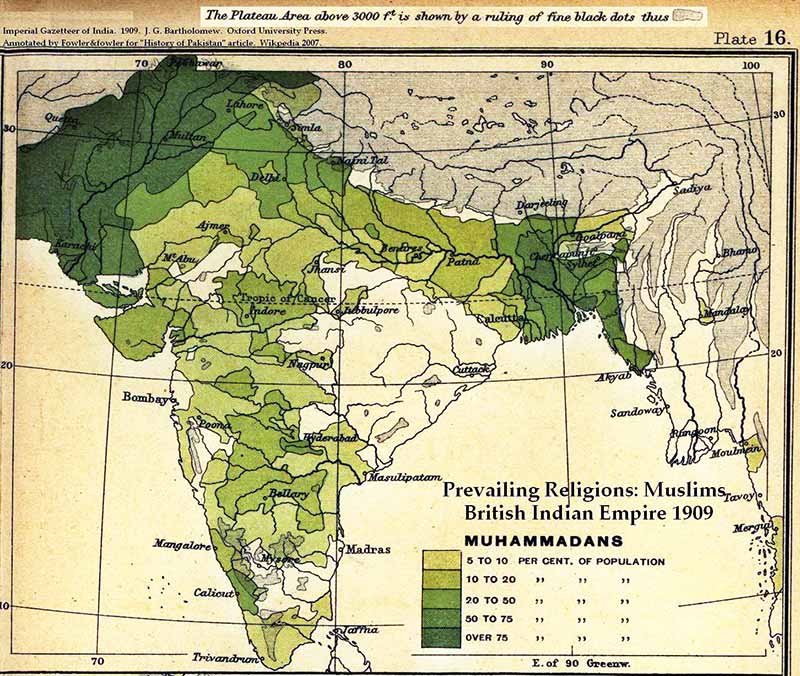

A 1909 Map of India portraying the population density of Muslims

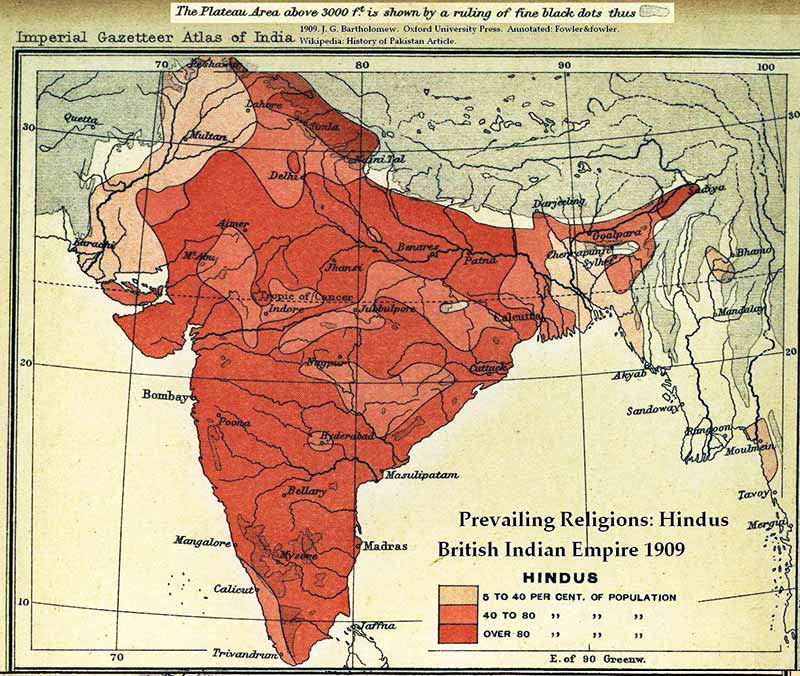

A 1909 Map of India portraying the population density of Hindus

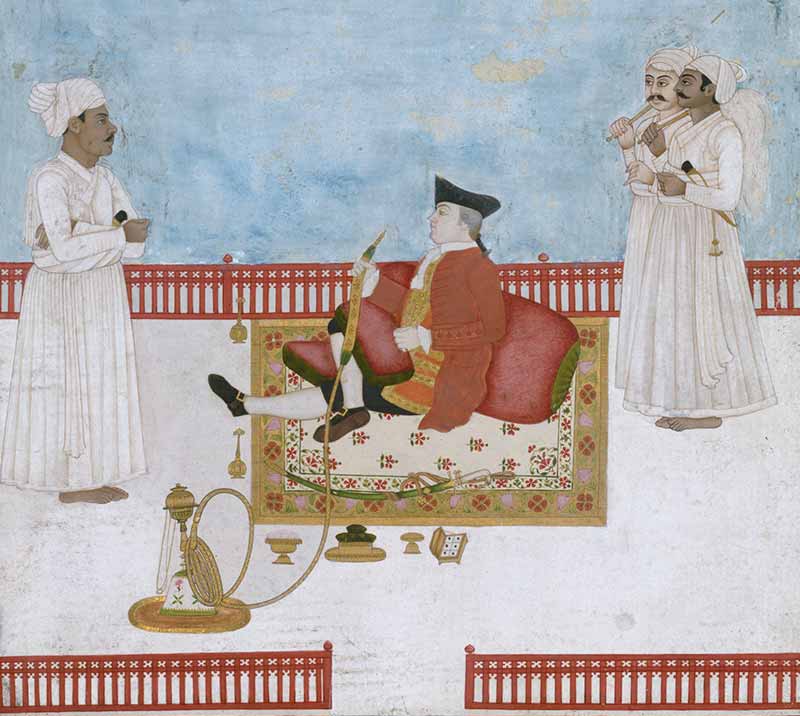

English traders established commercial relations in various regions of India in the 18th Century. The Mughal emperors ruled from Delhi, essentially a Sunni Muslim state. They were in constant conflict with the Maratha Empire, which held political sway over large swaths of the subcontinent, promoting Hindu culture. The East India Company was formed in 1600, initially to manage the spice trade with India. When Indian princes faced succession crises or attempted to increase their holdings, they sometimes allied with the English East India Company, who had their own forces stationed nearby and could step in and make a difference in local squabbles. By the early 19th Century, The Company had secured authority over tens of thousands of square miles, ruling through proxy princes and military conquest of major cities and provinces, forcing the Mughal emperors out of power and defeating the Marathas in three wars. The Company provided day-to-day administration of the “British Possessions” after the Battle of Plassey in 1757 until the British government ousted the Company in 1858.

An officer of the East India Company, circa 1760-1764

Artist’s depiction of the Battle of Plassey, 1757

In 1857, an uprising of both Muslim and Hindu Indian army units trained by the British, and supposedly loyal to the Crown, exploded in an uprising that resulted in massacres, atrocities, and the deaths of thousands of English and Indians. After brutally suppressing the rising, the British government took over administration the following year with Queen Victoria now proclaimed “The Empress of India.” Known as the British Raj, England ruled over what is today India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and parts of Afghanistan and Ceylon. They reorganized the army to exclude units of Brahmins and Muslims, replacing them with Sikhs and Baluchis, who had remained steadfast during the rebellion. The 1861 census “revealed that the English population in India was 125,945. Of these only about 41,862 were civilians as compared with about 84,083 European officers and men of the Army. In 1880, the standing Indian Army consisted of 66,000 British soldiers, 130,000 Natives, and 350,000 soldiers in the princely armies.”*

The 1857 mutiny was brutally suppressed and the leaders made an example of by execution

The Victoria Memorial Hall in Kolkata, India—the largest monument to a monarch anywhere in the world, standing in 64 acres of gardens—was built between 1906 and 1921 by the British government and is dedicated to the memory of Queen Victoria, Empress of India from 1876 to 1901

The British instituted reforms, one of which challenged the Church. Believing that the religions and traditions of the millions of Muslims and Hindus were too deeply imbedded and resistant to “social change” and conversion to Christianity—which often resulted in violent protest and riot—the government made it official policy to prevent mission work. Evangelism continued nonetheless, as it had when the Company tried to prevent proselytizing.

A painting showing an open-air restaurant in Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan, opposite the Wazir Khan Mosque

Britain exported the industrial revolution to India, building railroads, canals, bridges, roads, and establishing telegraph communication across the subcontinent. Much of the cost of “infrastructure” was borne by the Indians themselves, but the upper echelons of control remained in the hands of Europeans. With the sixty-year boom in industry came agricultural change, both good and bad. Food-grains, tea, and cotton flowed into world markets. When parts of India suffered from famine and drought—as had been the case in the past and exacerbated by the export of food in the present, as had happened in Ireland—multitudes of small farmers lost their animals and land from disease and debt; peasants and city-dwellers alike died by the “tens of millions.” Recent historians claim that more than fifty million people died, and blame it all on British imperialism and control of transportation and export, arguments hotly disputed by the older historians of the period.

The Delhi Durbar elephant carriage of the Maharaja of Rewa during the Great Durbar of 1902-3, organized by the Viceroy Lord Curzon, and which was as much a celebration of British rule in India as a commemoration of the Coronation of Edward VII, Queen Victoria’s son and successor to the throne of Great Britain, and thus Emperor of India

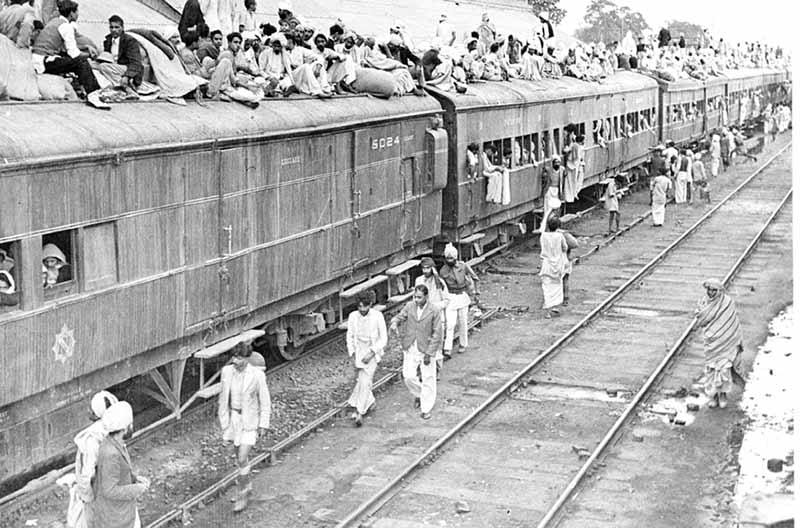

A huge middle class arose during the period of the Raj and some British viceroys pursued efficiency and reform. By the 20th Century, Indian laborers and soldiers could be found everywhere in the empire. Growing dissatisfaction with British rule in India accompanied the early years of the 20th Century and talk of independence grew accordingly. Home rule leagues grew and leaders such as Mohandas Gandhi stepped forward for reform and independence, particularly during the First World War and the following two decades. Conservative British politicians dug in their heels against dissolution of the empire, but reforms were never enough to quell the nationalist movements advocating independence. Muslim politicians had been given political control over a number of provinces as the movement for independence increased with the prosecution of the Second World War. Military mutinies in India accelerated the machinery of the post-war Labor Government in Britain to move forward with independence and dissolution of the British Empire. Extreme violence broke out between Muslims and Hindus in the Punjab and Bengal, and continued unabated with the transfer of power from Parliament in London to the two new states in August of 1947—India and Pakistan.

Gandhi in 1947, with Lord Louis Mountbatten, Britain’s last Viceroy of India, and his wife Lady Edwina Mountbatten

A refugee special train at Ambala Station, Haryana, India during the Partition of India in 1947

Recent demographic and census studies have declared India the most populous nation on earth, or nearly so. They possess a burgeoning hi-tech and medical industry, the sixth largest number of millionaires in the world, the sixth largest number of nuclear warheads, and a continuing stratified population, with millions in almost absolute poverty, speaking twenty-two different languages. India is still home to Muslims (14.2%) and Hindus (c. 80%), with a growing Christian Church of thirty-two million (less than 2% of the population). The first two religions still hate each other and Christians, and prove it from time to time with mortal conflicts. In Pakistan, 96.5% of the people are Muslim. The blessings of independence have come at great cost—a price India and Pakistan accepted as the price of doing business with the world without John Company or Her/His Majesty’s interference.

Lord Mountbatten swears in Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru as the first Prime Minister of free India at a ceremony held on August 15, 1947

*Cited in Robinson, Ronald Edward, & John Gallagher. 1968. Africa and the Victorians: The Climax of Imperialism. Garden City, NY: Doubleday

Image Credits: 1 Map of Muslims (wikipedia.org) 2 Map of Hindus (wikipedia.org) 3 East India Company official (wikipedia.org) 4 Battle of Plassey (wikipedia.org) 5 Execution of mutineers (wikipedia.org) 6 Victoria Memorial Hall (wikipedia.org) 7 Lahore, Pakistan (wikipedia.org) 8 Elephant carriage (wikipedia.org) 9 Ghandi with Lord and Lady Montbatten (wikipedia.org) 10 Refugee train (wikipedia.org) 11 First Prime Minister of Free India (wikipedia.org)