“And he gave some as apostles, and some as prophets, and some as evangelists, and some as pastors and teachers, for the equipping of the saints for the work of service to the building up of the body of Christ.” (Ephesians 4: 11, 12 NASB)

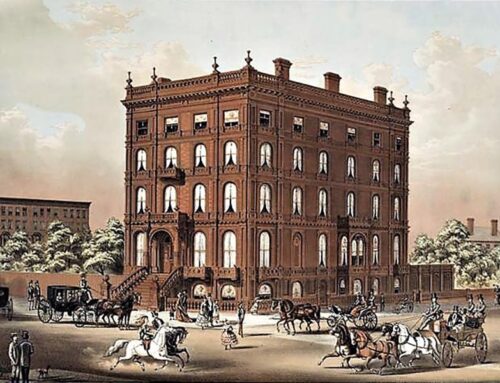

Whitefield Preaches in Philadelphia,

May 10, 1744

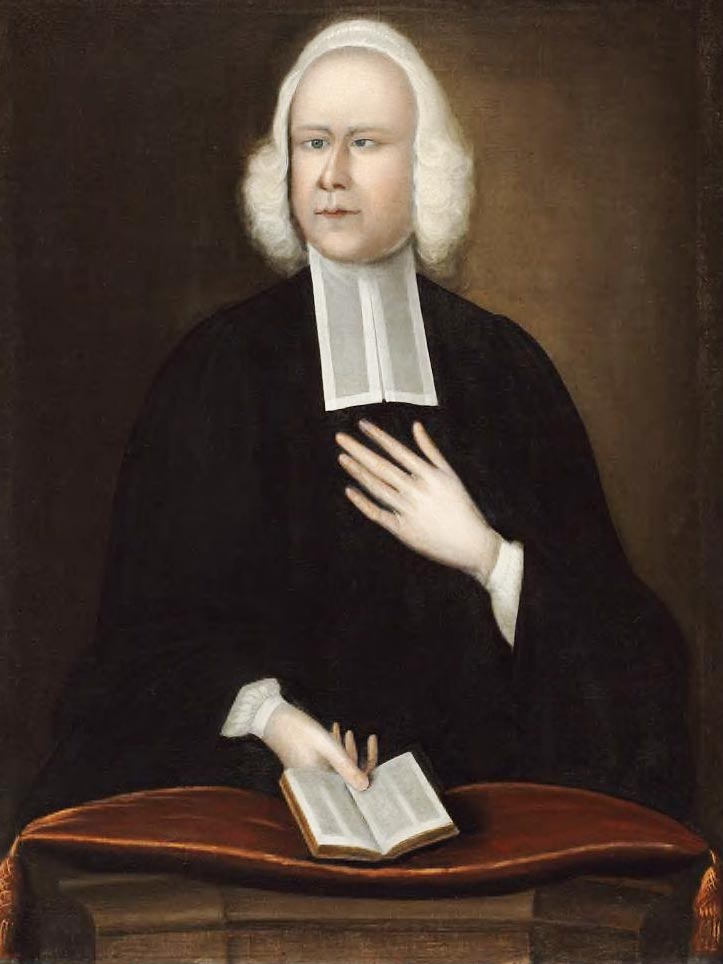

![]() n his lifetime he preached an estimated 18,000 times and reached about ten million hearers. His sermons were reprinted countless times, and people in frontier regions were converted and blessed without ever hearing his stentorian voice. He lived in the middle of the 18th century, so he spoke without electronic amplification or collecting his auditors in sports stadiums. He preached fourteen times in Scotland, once to a crowd estimated at 20,000. In Boston, Massachusetts he addressed about 20,000 people on Boston Commons in a colony with a total population of about 17,000. He was cross-eyed and mocked by his enemies as “Dr. Squintum”, and was consistently opposed by the mainstream clergy, both conservatives and liberals. He was a bold Calvinist in theology and gave no altar calls, only calls to repentance and faith. Multiple thousands came to sincere faith in Christ. He was evangelist George Whitefield, likely the most famous individual in American colonial history.

n his lifetime he preached an estimated 18,000 times and reached about ten million hearers. His sermons were reprinted countless times, and people in frontier regions were converted and blessed without ever hearing his stentorian voice. He lived in the middle of the 18th century, so he spoke without electronic amplification or collecting his auditors in sports stadiums. He preached fourteen times in Scotland, once to a crowd estimated at 20,000. In Boston, Massachusetts he addressed about 20,000 people on Boston Commons in a colony with a total population of about 17,000. He was cross-eyed and mocked by his enemies as “Dr. Squintum”, and was consistently opposed by the mainstream clergy, both conservatives and liberals. He was a bold Calvinist in theology and gave no altar calls, only calls to repentance and faith. Multiple thousands came to sincere faith in Christ. He was evangelist George Whitefield, likely the most famous individual in American colonial history.

George Whitefield (1714-1770)

George Whitefield was born the seventh child and fifth son of a Gloucester inn-keeper. He exhibited an academic aptitude, but due to his low estate, entered Oxford as a servitor. While there, he fell under the influence of John Wesley and became a member of The Holy Club, a group of students whose main concerns were prayer, Bible study and piety. Whitefield had been attracted to the theatre and considered acting as a career. A deep spiritual awakening deflected his thespian pursuits, but the skills of public speaking in dramatic fashion never left him. They would, in fact, characterize his impassioned preaching of the Gospel.

Aerial view of the University of Oxford

Ordained as a minister in the Church of England, Whitefield early on sailed to Savannah, Georgia as parish priest. He would become closely associated with Bethesda Orphanage there his entire life. After a short tenure, he returned to England and began an evangelistic preaching ministry throughout the United Kingdom. With his powerful voice and animated style, Whitefield expounded the Scriptures, especially those regarding repentance and faith. Along with the Wesley brothers, these revivals within Anglicanism and among dissenting denominations resulted in what would eventually be known as Methodism, an entirely new denomination in itself. Their appeals for “heart religion” often met with an outpouring of emotional responses and professed conversions to Christ, and the formation of new chapels and churches where none existed before.

George Whitefield preaches to a crowd gathered in Bolton, England in June 1750

( CC BY-NC-ND ArtUK.org )

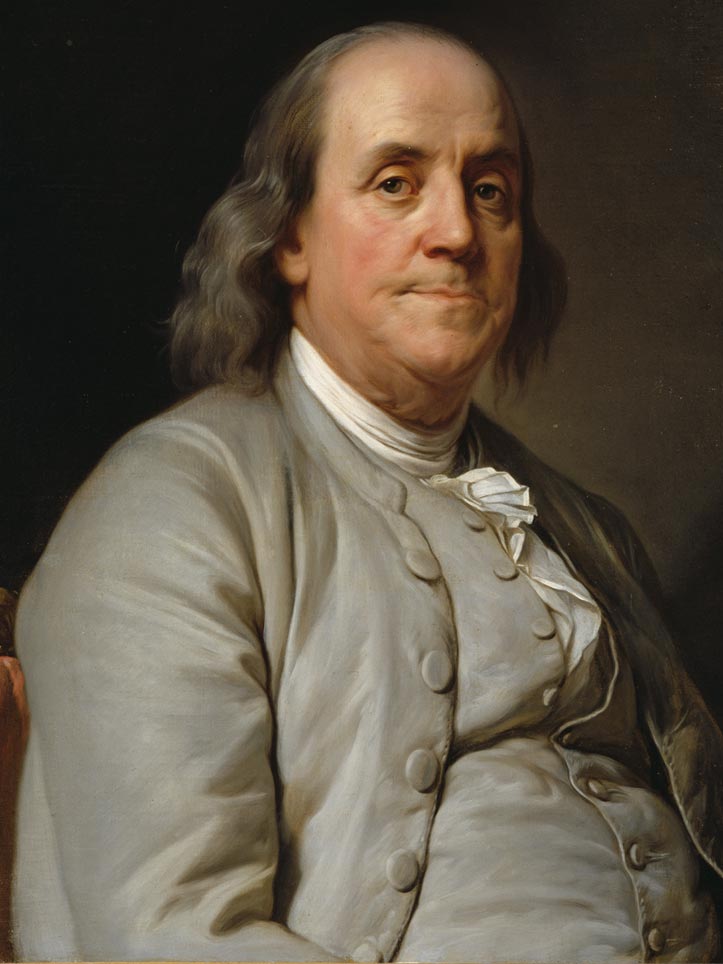

Whitefield returned to America in 1739 where, it turned out, the fields were “white unto harvest.” His first tour extended from New York to Savannah, with perhaps his most successful preaching stop in Philadelphia. Sensing a potential economic opportunity for his printing business, Benjamin Franklin negotiated the right to print the twenty-four-year-old Whitefield’s sermons and books, and though not a believer himself, also attended the services. The two men remained correspondents and close friends till Whitefield’s death in 1770. Whitefield crossed the Atlantic thirteen times and became the central figure of the “Great Awakening” in America.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790)

As historian Thomas Kidd observed:

“Whitefield played a key role in the emerging Anglo-American evangelical movement, but we should remember that the majority of conversions and revivals of the Great Awakening happened without him.

George Whitefield at the pulpit

Nonetheless, his trips to America, Scotland, and England resulted in multiple thousands of conversions. Sometimes churches were split, in other cases, pastors guided converts into the churches and continued preaching the new birth after the itinerant left. Controversy followed in the wake of the unapologetically Calvinistic Whitefield throughout his years of ministry, resulting in a break with John and Charles Wesley over their intransigent Arminian theology and perfectionism. Whitefield was also the most vocal advocate of preaching the Gospel to the slaves and took every opportunity to do so himself. He was mocked, beaten, and publicly ridiculed, but never lost sight of his calling as an evangelist. Lionized as the greatest preacher of his day, Whitefield holds a unique place in the history of revivals and the effect of the Gospel in America. Whitefield died in 1770, age fifty-five and was buried in Newburyport in Massachusetts. Few men in history have been so used of God to lead multitudes of people to personal faith in Christ. Would that more Whitefields be raised up and bring a new spiritual awakening in our country today.

Whitefield’s grave in the crypt of Old South Presbyterian Church, Newburyport, MA

( (CC) Dr Digby L. James )