“I will lead the blind by a way they do not know, In paths they do not know I will guide them I will make darkness into light before them And rugged places into plains These are the things I will do, And I will not leave them undone.” —Isaiah 42:16

John Milton Ducks Charles II, August 27, 1660

unhill Fields Cemetery in London contains the earthly remains of many prominent dissenters or “non-conformists” of England’s history. As an almost unknown historic site to most people, among the two thousand or so markers, Bunhill’s tombs include those of John Bunyan, author of Pilgrim’s Progress, John Owen, renowned Puritan theologian and chaplain to Oliver Cromwell, novelist Daniel Defoe, George Fox, who is considered the father of “Quakerism,” Isaac Watts, the father of English hymnody, and Susannah Wesley, the twenty-fifth child in her family and mother of nineteen, including the preachers and hymn-writers John and Charles. Along with Bunyan, perhaps the most universally known denizen of Bunhill is John Milton, the Puritan poet, political polemicist, civil servant, and historian of the 17th century—the author of Paradise Lost.

unhill Fields Cemetery in London contains the earthly remains of many prominent dissenters or “non-conformists” of England’s history. As an almost unknown historic site to most people, among the two thousand or so markers, Bunhill’s tombs include those of John Bunyan, author of Pilgrim’s Progress, John Owen, renowned Puritan theologian and chaplain to Oliver Cromwell, novelist Daniel Defoe, George Fox, who is considered the father of “Quakerism,” Isaac Watts, the father of English hymnody, and Susannah Wesley, the twenty-fifth child in her family and mother of nineteen, including the preachers and hymn-writers John and Charles. Along with Bunyan, perhaps the most universally known denizen of Bunhill is John Milton, the Puritan poet, political polemicist, civil servant, and historian of the 17th century—the author of Paradise Lost.

John Milton (1608-1674)

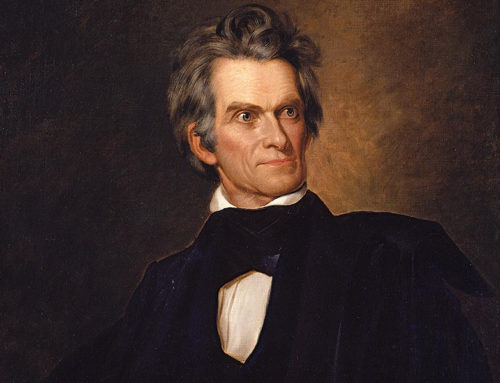

John Milton was born in London in 1608, which makes him a contemporary of Charles II, Samuel Rutherford, John Owen, Oliver Cromwell, and the men of the Westminster Assembly that produced the famous Confession of Faith. His father had abandoned the Roman Catholic religion of the Milton family and had prospered greatly as a scrivener in London. Young John’s education came from a Scottish private tutor who proved his worth and John’s native genius by qualifying him to enter Christ’s College, Cambridge in 1625, to prepare for ministry in the Church of England. He befriended Roger Williams, later of Rhode Island fame, who taught him Dutch in exchange for lessons in Hebrew.

An 1837 view of Cheapside street in London where Milton was born

Christ’s College, Cambridge, founded in 1437

Milton’s first publications date from this period, mostly poetry. Of serious demeanor, he also was unafraid of criticizing the curriculum of the college and would later serve as an educational reformer. From 1635-41 Milton’s autodidactic nature enabled him to conduct intensive study on his own at his father’s home, mastering at least six languages as well as history and philosophy, making him, perhaps, the most knowledgeable poet in history. He spent more than a year travelling across Europe, conversing with and learning from intellectuals, linguists, poets, and artists. He met Galileo, at the time under house arrest in Italy. He studied Roman Catholicism in practice, toured the Vatican library, and spent time in Geneva, Switzerland. The peripatetic genius was now providentially ready for his life’s work and literary immortality during the upheavals of the English Civil Wars, Interregnum and Restoration of the Stuart monarchy.

Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)

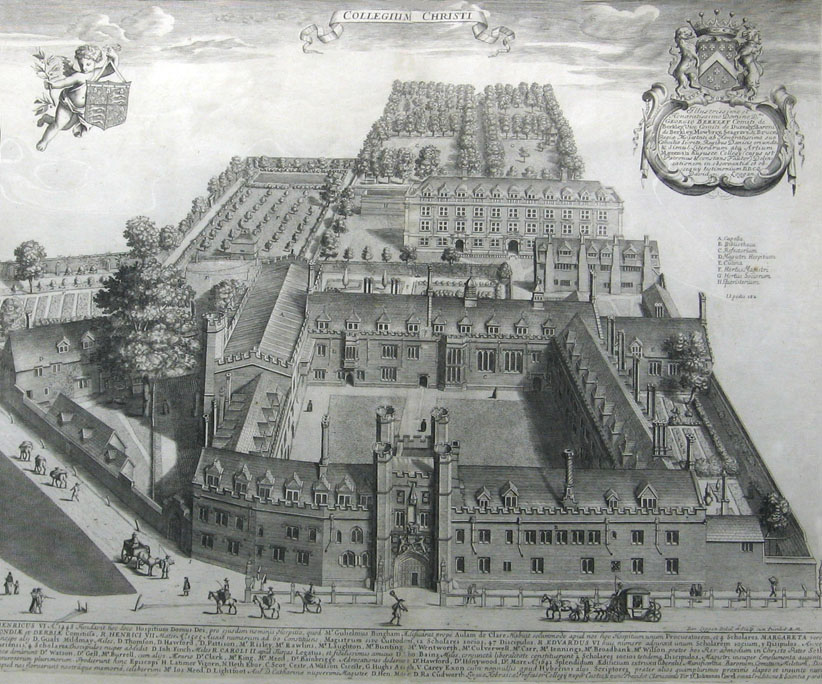

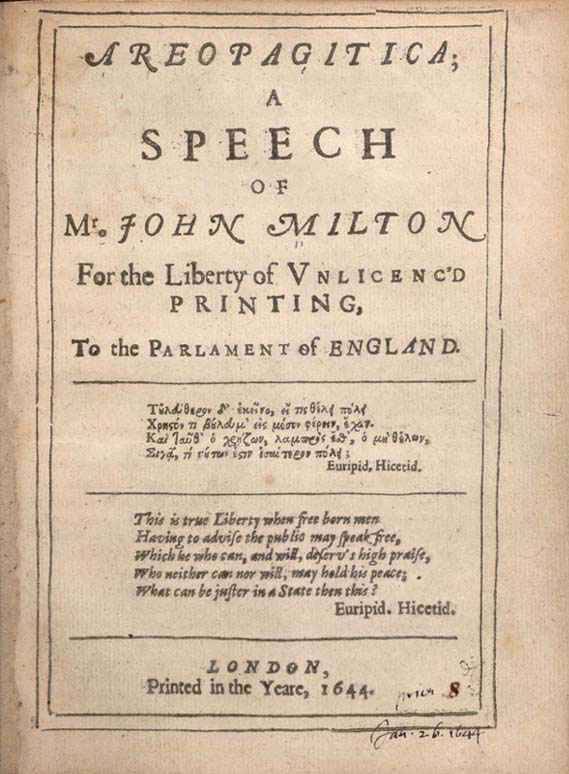

Milton’s Puritan convictions took immediate wings with written tracts against prelacy and Erastianism, and he taught in a school. The thirty-five-year-old poet and pamphleteer married a sixteen-year-old bride, who deserted him within thirty days. They reconciled and had four children together, although Milton published several controversial pamphlets arguing that divorce was biblical, a position for which he was roundly condemned. Among his most admired works was Areopagitica, a treatise on liberty which identified him with the views of Parliament in the ongoing controversy with King Charles I. Milton supported the Commonwealth and republican ideals regarding the King’s accountability to the people. Milton also agreed with and justified the regicide of Charles, in disagreement with his Scottish brethren. Parliament hired him in 1649 as a propagandist and correspondence secretary to foreign powers.

First addition title page of Miltson’s Areopagitica from 1644

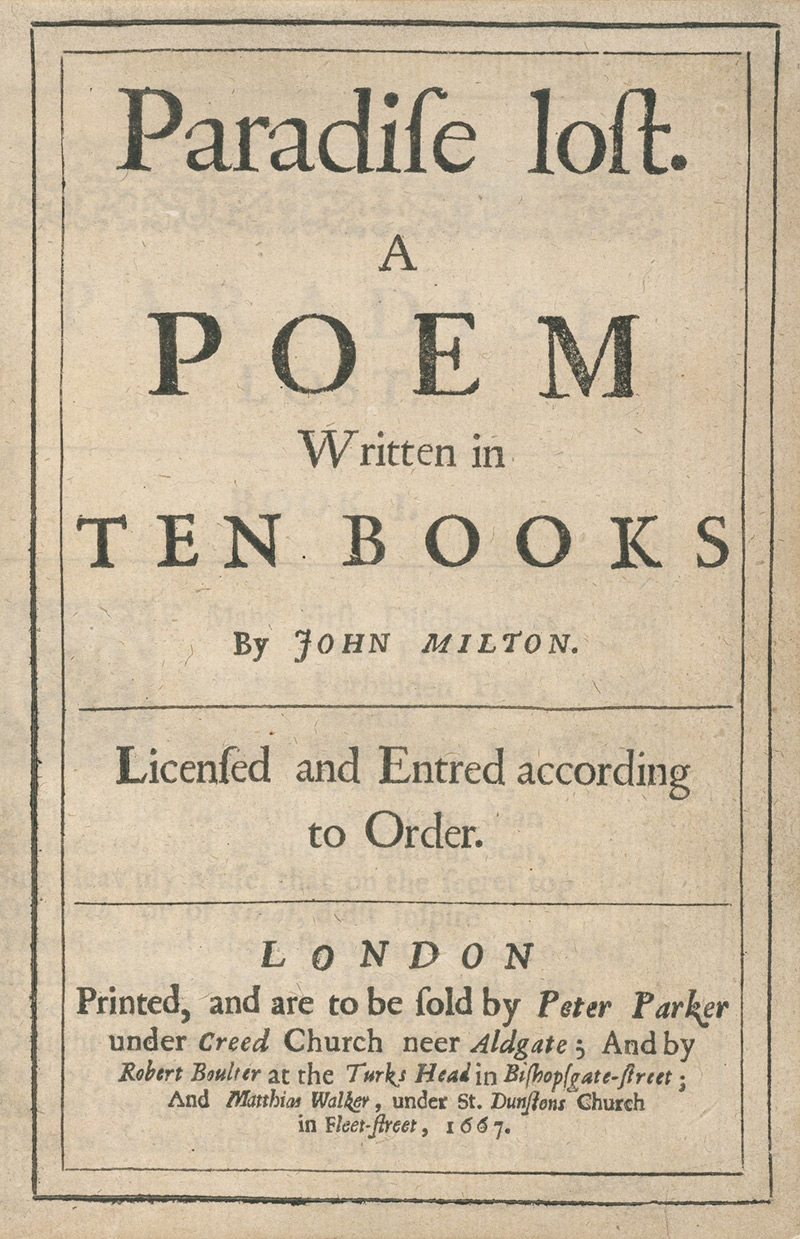

Although Milton wrote, often in Latin, polemical defenses of the English revolt against the king and in justification of Parliament’s actions, his eyesight declined until he was totally blind by 1652 (age 44). He nonetheless continued writing poetry and propaganda, with great success, by dictation to an amanuensis. His greatest work, the blank-verse epic poem Paradise Lost and the follow up Paradise Regained were produced over a six-year period through dictation to copyists and to his own daughters.

Having become totally blind by 1652, Milton is shown dictating Paradise Lost to his daughters

The collapse of the Commonwealth did not deter Milton from continued political writing against the monarchy and the new public sentiment that brought about its Restoration under Charles II.

As a supporter of the regicide, Milton would become a target of the new king, whose refusal to pardon anyone who had played any role in the execution of his father placed the blind poet in mortal jeopardy. His friends forced him into hiding when Charles arrived in England. They held a mock funeral for Milton on August 27, 1660. Charles II commented that he “applauded his [Milton’s] policy in escaping the punishment of death by a reasonable show of dying,” but insisted on a public spectacle nonetheless by having Milton’s writings burned by the public hangman.

The coronation of King Charles II of England (1630-1685)

The Puritan poet reemerged after a general pardon, was imprisoned, and released, likely due to political friends in high places. He died, aged sixty-four in 1674. His theological views were sometimes considered heterodox by the best Puritans and his political views came close to getting him executed. His poetry, however, has endured as some of the greatest works in the English language, especially Paradise Lost; much of his greatest work was written during his twenty-two years of blindness.

Title page from Milton’s Paradise Lost, 1667

Image Credits: 1 John Milton (Wikipedia.org) 2 Cheapside (Wikipedia.org) 3 Christ’s College (Wikipedia.org) 4 Galileo Galilei (Wikipedia.org) 5 Areopagitica (Wikipedia.org) 6 Milton dictating (DigitalCommonwealth.org) 7 Coronation of Charles II (Wikipedia.org) 8 Paradise Lost title page (Wikipedia.org)