“The city shall be under the ban, it and all that is in it belongs to the Lord; only Rahab the harlot and all who are with her in the house shall live, because she hid the messengers whom we sent.” —Joshua 6:17

Mary Surratt Executed, July 7, 1865

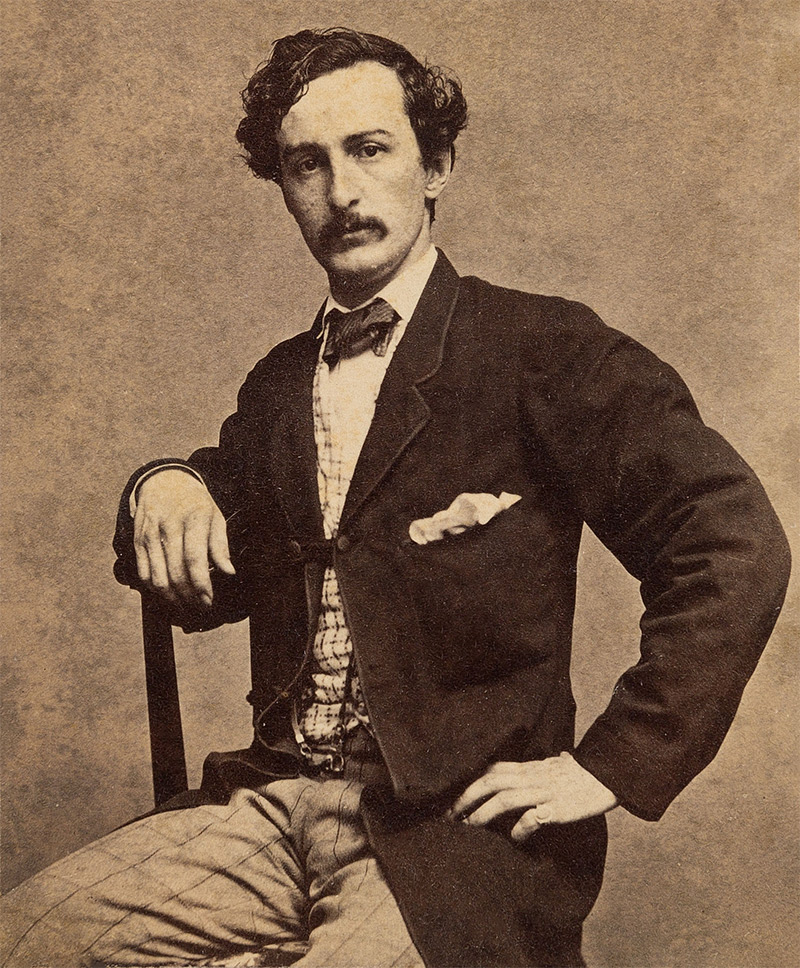

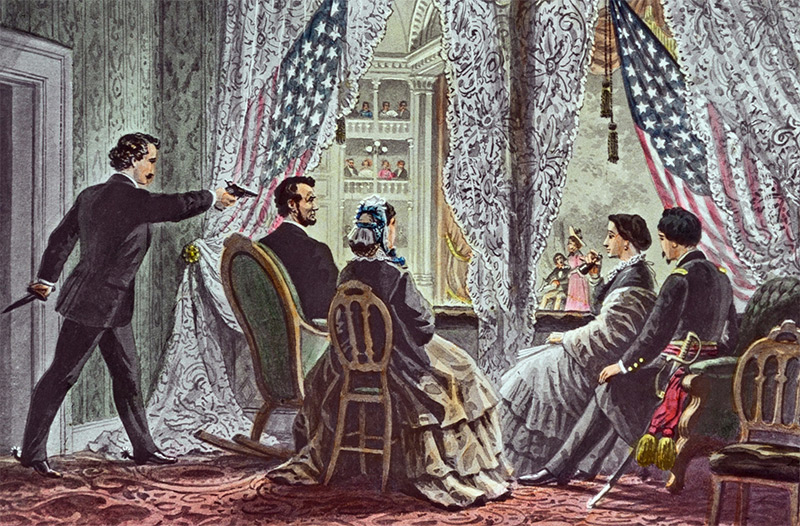

n April 14, 1865, the popular stage actor John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln. Booth was the leader of a conspiracy to kidnap the President and hold him for ransom to grant the Confederacy their independence and end the war. The madcap scheme went awry when the kidnap plot could not be pulled off. Booth and his fellow conspirators then determined to kill the President, plus the next two in line for the office, Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State, William H. Seward. After the kidnap plot failed, one of the conspirators, John Surratt, a courier for the Confederate Secret Service, dropped out of the gang and fled northward toward Canada. The others tried to carry out the assassinations. Only Booth succeeded.

n April 14, 1865, the popular stage actor John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln. Booth was the leader of a conspiracy to kidnap the President and hold him for ransom to grant the Confederacy their independence and end the war. The madcap scheme went awry when the kidnap plot could not be pulled off. Booth and his fellow conspirators then determined to kill the President, plus the next two in line for the office, Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State, William H. Seward. After the kidnap plot failed, one of the conspirators, John Surratt, a courier for the Confederate Secret Service, dropped out of the gang and fled northward toward Canada. The others tried to carry out the assassinations. Only Booth succeeded.

John Wilkes Booth (1838-1865)

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater in Washington, DC, April 14, 1865

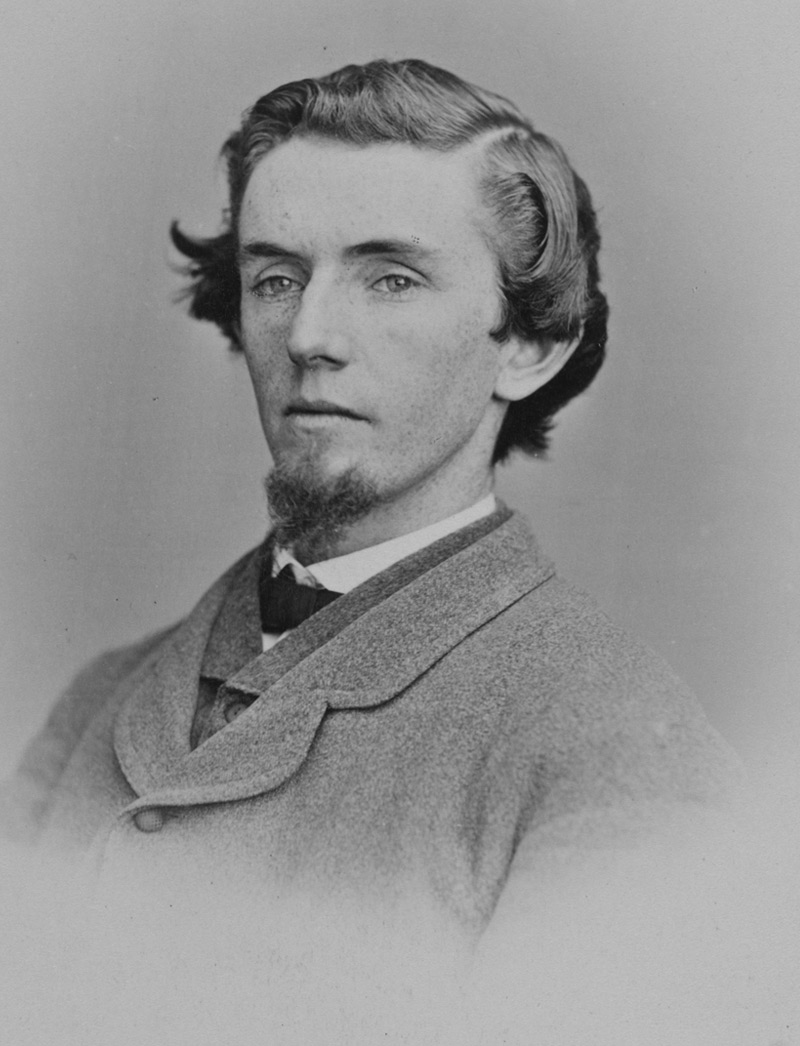

Upon the death of President Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton essentially seized control of both the government and the investigation, directing the officers who rounded up the would-be assassins and tracked the fleeing Booth through Virginia. Booth was trapped in a burning barn and shot to death by a trooper named Boston Corbett. The other suspects, including the rest of the gang who had been in on the kidnapping and murder plot, the doctor who set Booth’s broken ankle, and Mary Surratt, the proprietor of the boarding house where the plotters occasionally met, were rounded up and imprisoned. John Surratt, on an unrelated secret mission in New York, eluded pursuers, escaping to Canada and then to Europe.

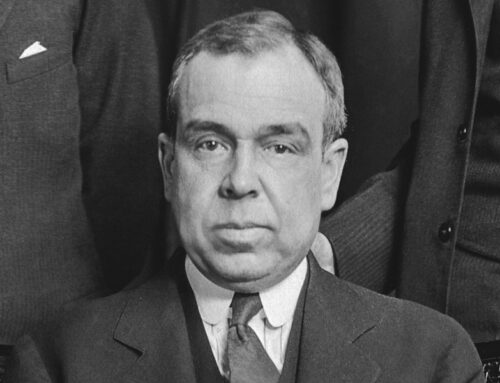

Edwin Stanton (1814-1869) United States Secretary of War (1862-68)

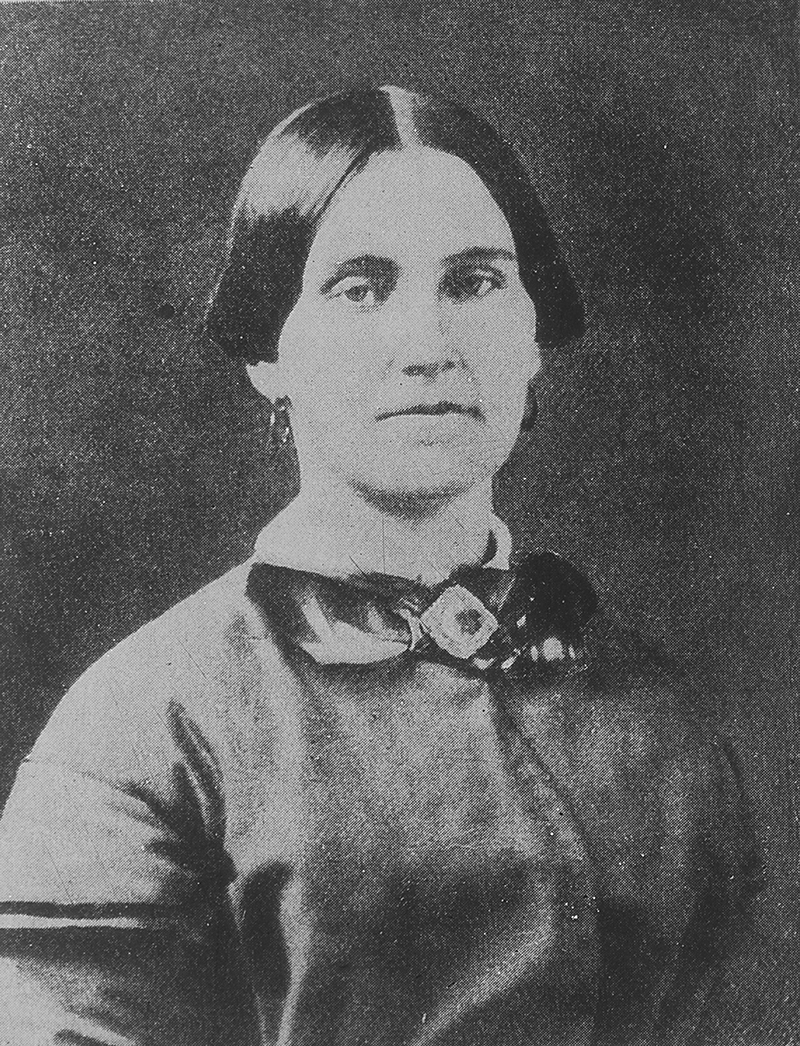

Mary Surratt (1820-1865)

John Surratt (1844-1916)

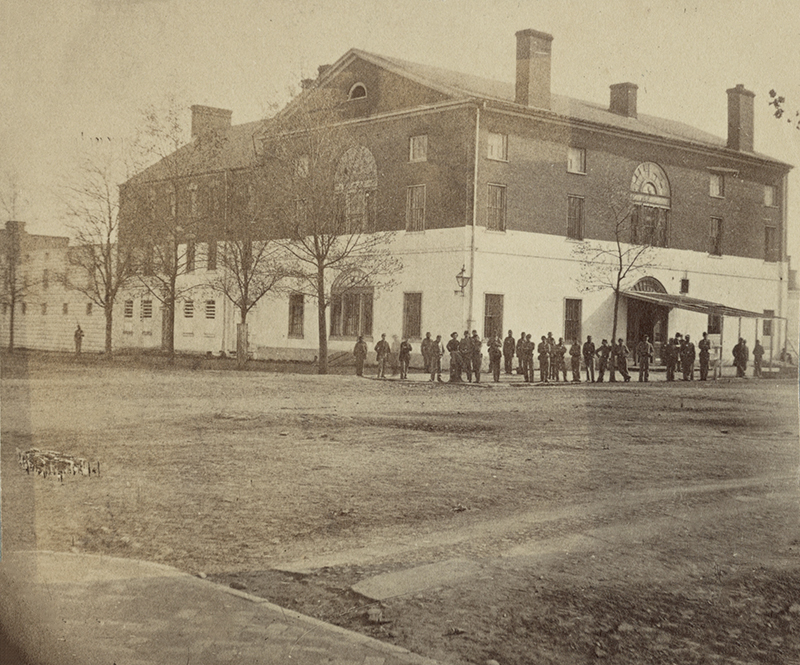

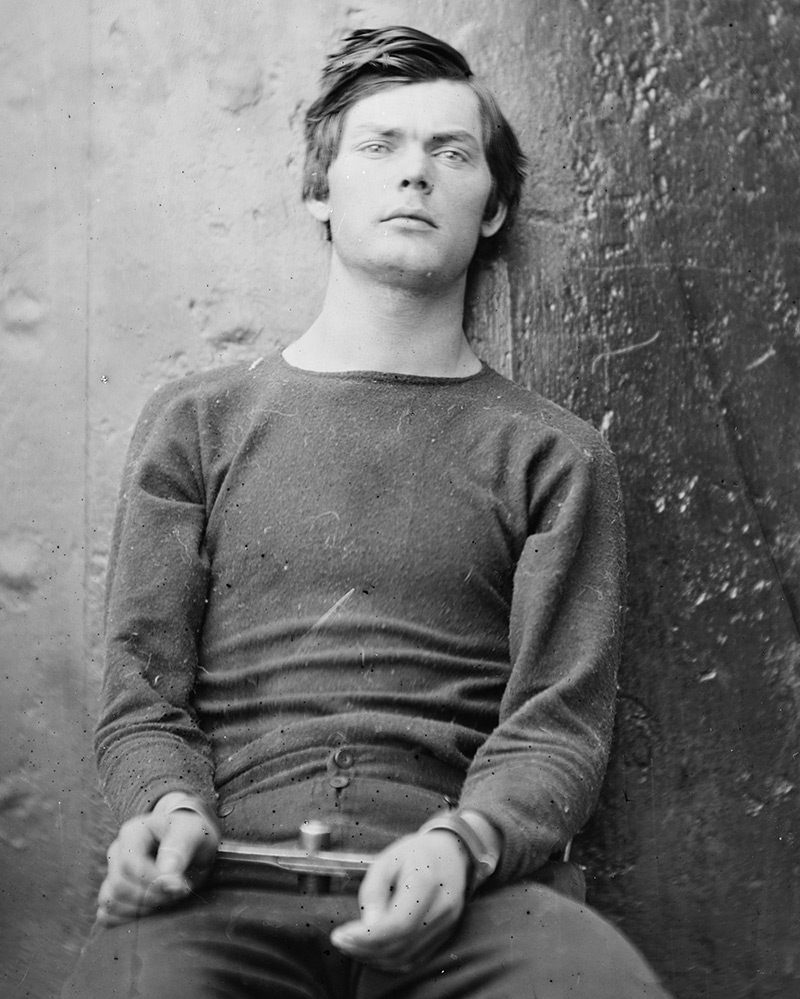

Stanton determined that all the accused civilians would receive a military trial, thus precluding how evidence could be gathered and waiving other rules normal to civilian courts. The suspects were kept shackled and hooded in isolation at Old Capitol Prison and the Washington Arsenal. Mary Surratt, mother of three, proved the most troubling case of all the accused conspirators. The Surratt family were Confederate-sympathizing Marylanders and the wife and children, devout Roman Catholics. Mary Surratt’s alcoholic husband had died in 1862 and she had moved to a D.C. townhouse and took in boarders. The Surratt family had offered shelter to spies and couriers in years past, and young John abandoned his studies for the priesthood to work for the Confederate Secret Service. The Booth cabal met at the boarding house periodically and three of them—Booth, Atzerodt and Powell—rented rooms at different times. The military tribunal had little or no direct evidence that confirmed Mary Surratt’s involvement in the assassination conspiracy. She admitted her Southern sympathies but denied she had any knowledge of the murder plot.

Temporarily serving as the Capitol of the U.S. (1815-1819) the Old Brick Capitol building in Washington, DC. also served as a private school, a boarding house, and, during the American Civil War, a prison known as the Old Capitol Prison.

Lewis Powell (1844-1865)

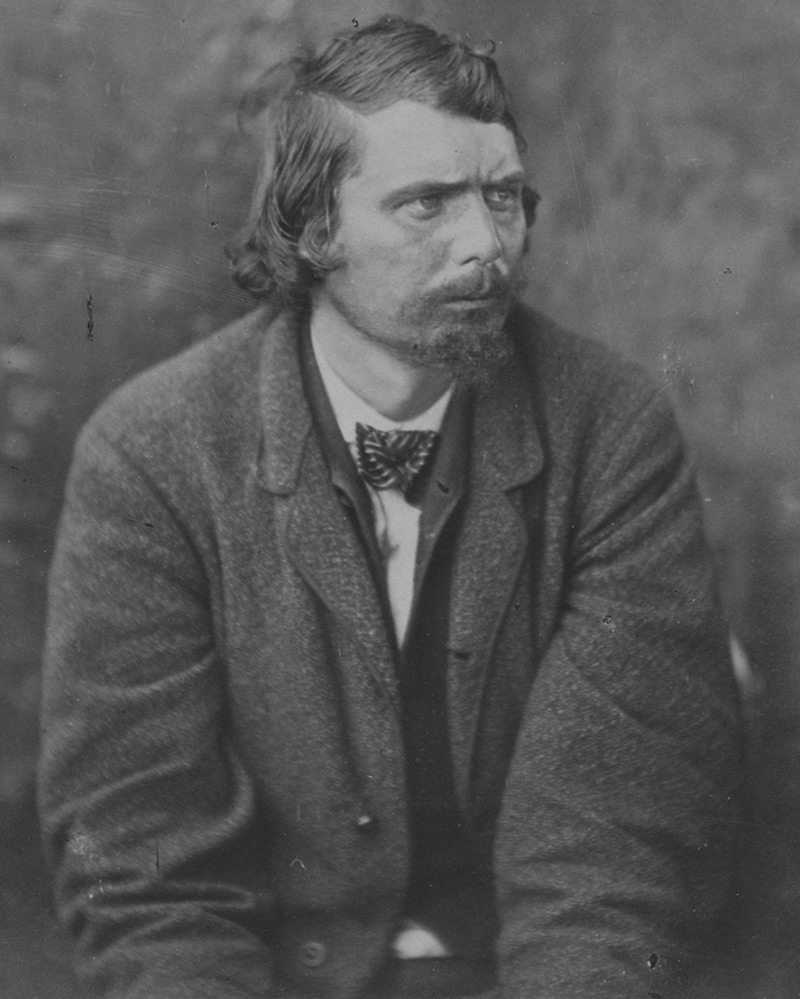

George Atzerodt (1835-1865)

Maryland Senator Reverdy Johnson took on Mary’s case, but the tribunal questioned his loyalty and “poisoned the well,” effectively damaging his ability to represent her. A Vermont journalist, recently turned attorney, Frederick Aiken, had offered his services to Jefferson Davis when the Confederacy was formed. However, he served in the Union army during the war, was wounded and returned home a brevet Colonel. He was a newly minted lawyer and was tapped by Johnson to take over the case. Woefully inexperienced and up against a military tribunal presided over by General David Hunter (known for disobeying superiors’ orders and whose career was filled with atrocities on behalf of the Union, burning homes and making war on civilians), Aiken’s case seemed doomed from the start.

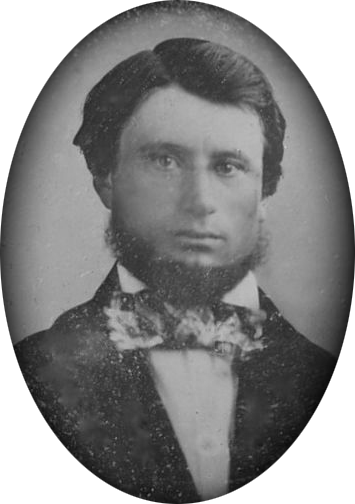

Frederick Aiken (1832-1878)

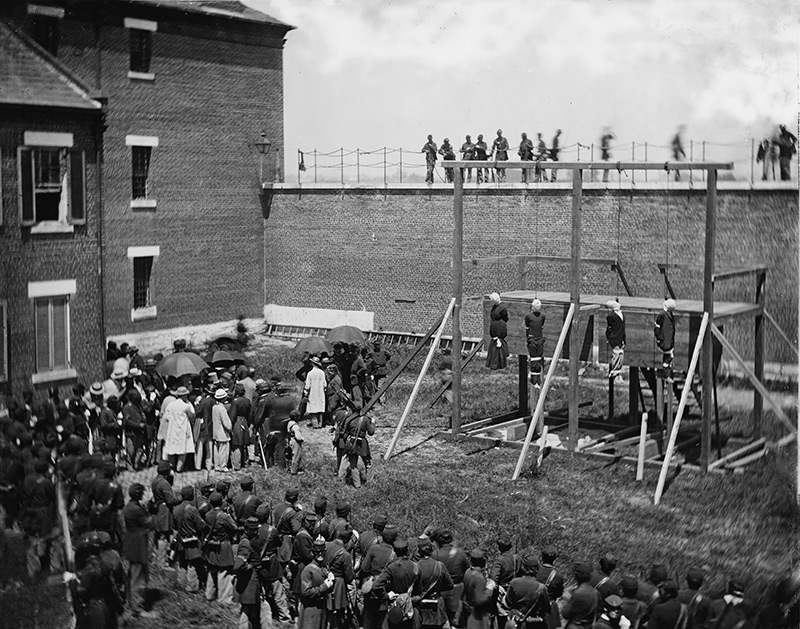

The case against Mary hinged on two witnesses, John Lloyd, a drunken tenant on property owned by the Surratts and Louis Weichmann, a friend of John Surratt, boarder at the Surratt house, and clerk in Stanton’s War Department. Both men implicated Mary Surratt in the conspiracy, their questionable character and suspected perjury mishandled by the defense. Lloyd had supplied Booth with weapons and supplies but escaped punishment for his testimony against Mary. Of the dozens of people arrested and examined, four received the death penalty, including Mary. The majority of the tribunal voted to not hang Mary, in an attempt to intervene in her becoming the first woman officially executed by the United States government. President Johnson did not rescind the tribunal’s sentence for her; some historians believe he never received the amended appeal, others believe he was frightened of the power of the War Department. John Surratt was run to ground in Egypt by agents of the American Government. He stood trial eighteen months after his mother was hanged, but in a civilian court. Eight of the twelve jurors declared him not guilty for the assassination of President Lincoln, the jury was thus hung, and not Johnny Surratt. He was released and lived until 1916, dying at the age of 72.

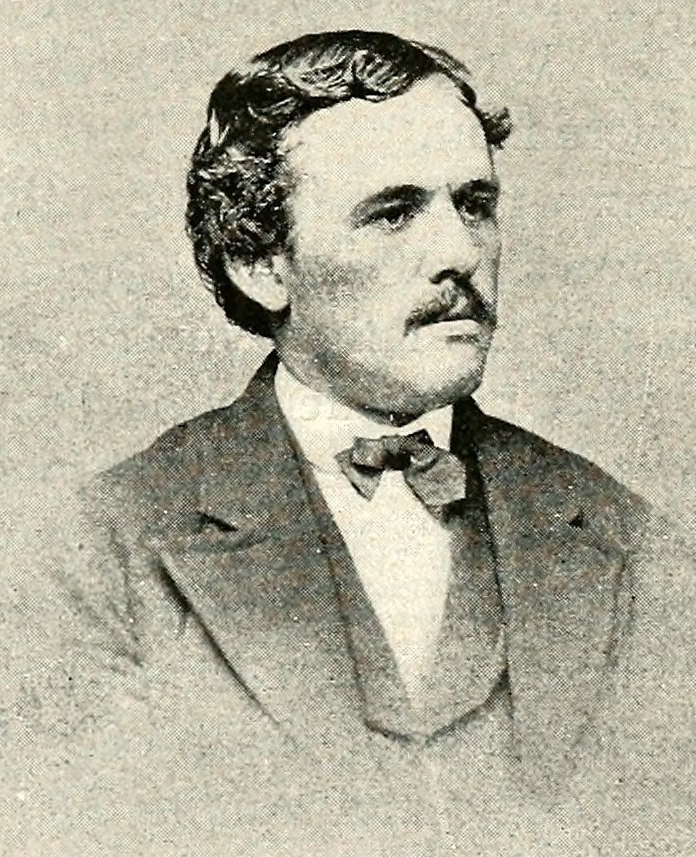

Louis Weichmann (1842-1902), one of the primary witnesses for the prosecution in the trial of the alleged assassination conspirators

Execution by hanging of four convicted conspirators: Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt

Note: There are good modern biographies of both Mary and John Surratt, as well as a cottage industry of books on the Lincoln assassination.

Image Credits: 1 John Wilkes Booth (Wikipedia.org) 2 Lincoln Assassination (Wikipedia.org) 3 Edwin Stanton (Wikipedia.org) 4 Mary Surratt (Wikipedia.org) 5 John Surratt (Wikipedia.org) 6 Old Capital Prison (Wikipedia.org) 7 Lewis Powell (Wikipedia.org) 8 George Atzerodt (Wikipedia.org) 9 Frederick Aiken (Wikipedia.org) 10 Louis Weichmann (Wikipedia.org) 11 Conspirator executions (Wikipedia.org)