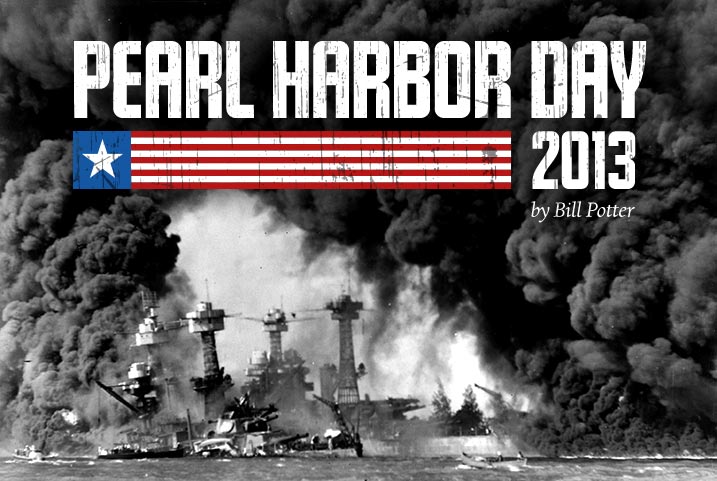

Two years ago I had the privilege of visiting Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on the 70th Anniversary of the battle. I visited the USS Arizona Memorial where more than 1,000 American sailors died in the Japanese surprise attack. I visited the Punch Bowl Cemetery, the final resting place of more than 53,000 American servicemen. I strode around the Battleship USS Missouri anchored at Ford Island—the ship upon which the Japanese formally surrendered to General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral Chester Nimitz to end World War II. Finally, I attended the formal memorial service for the men who died on that day in which the future of the world seemed to hang in the balance.

During that memorable visit I interviewed or assisted in interviewing about twenty five survivors from that “day that will live in infamy.” Each one had a different story and role to play, however small, in that history-changing event. The experiences of each man were seared into their memory and each one knew one, sometimes many, men who lost their lives in the attack. The oldest sailor I met was the last surviving officer of the Arizona, then ninety-six years old. His son had brought him there one last time to visit the scene of the most dramatic part of his life. He was dressed in uniform and told amazing stories of survival and sacrifice in minute detail. He also was suffering from Alzheimer’s and would not remember any of us an hour after the interview.

One of my favorite interviews was with a sailor aboard the Battleship USS California, with a crew that was renowned for its athletic prowess in defeating other ships in sports competitions. The man who told me his story said he had gotten up early on that Sunday morning and dressed in his football uniform for a game scheduled with another battleship team. When the call to battle rang out, all sailors, no matter their stage of dress or undress, had to race to their duty stations. His was in the crows nest. There he sat throughout the battle in his football gear, at eye level with the Japanese torpedo bombers, whose pilots waved at him as they dropped their tin fish to destroy American vessels. The California settled into the mud of Pearl Harbor only to be resurrected, reconstructed and sent to battle again more than two years later.

Another sailor was responsible for raising the signal flags on his ship by climbing the ropes in full view of the attacking planes. He told me that a Japanese plane flew directly at him firing; in the micro-second he had left wondered if he should face his attacker or be shot in the back. In the event, the machine gun bullets bracketed his position and he survived the battle.

Perhaps the most striking and surprising information that came from those interviews had nothing to do with the courage and perseverance of the men, nor their remarkable memories, nor their longevity having come through the ardors of combat in the World War. What impressed me most, was most distressing for me, was their uniform denial that God had anything to do with their survival (some of them almost miraculous) or their lives, in any way. They almost uniformly denied providence and embraced luck and chance as the only explanation for their being alive today. Some of them still used profane language. Only a few attended church services. I realized that these ninety-something-year-old veterans were as spiritually lost as the day they were born.

We can never take for granted that men—and women for that matter—who have lived long lives, perhaps done great deeds, and come close to death, have ever humbled themselves before God’s almighty sovereignty over their lives and sought His divine Mercy and Grace. He has provided many years to repent and believe in Christ; yet they have remained spiritually dead, attributing their survival to good luck, false gods, or their own fiercely independent sovereign will. Now is the day of repentance; having survived withering fire of Pearl Harbor, or any other near miss, our days are still only as long as the withering grass.