“A horse is prepared for the day of battle, but victory is of the LORD.” —Proverbs 21:31

The Battle of Antietam, September 17, 1862

fter fifteen months of brutal combat—stretching from Arizona Territory to the eastern seaboard, as well as across the Atlantic Ocean—Union and Confederate armies met in the rolling countryside of western Maryland, in a small town named Sharpsburg, to fight a battle on a Wednesday, which proved to be the bloodiest single day in American history. It still is.

fter fifteen months of brutal combat—stretching from Arizona Territory to the eastern seaboard, as well as across the Atlantic Ocean—Union and Confederate armies met in the rolling countryside of western Maryland, in a small town named Sharpsburg, to fight a battle on a Wednesday, which proved to be the bloodiest single day in American history. It still is.

The Battle of Antietam, September 17, 1862

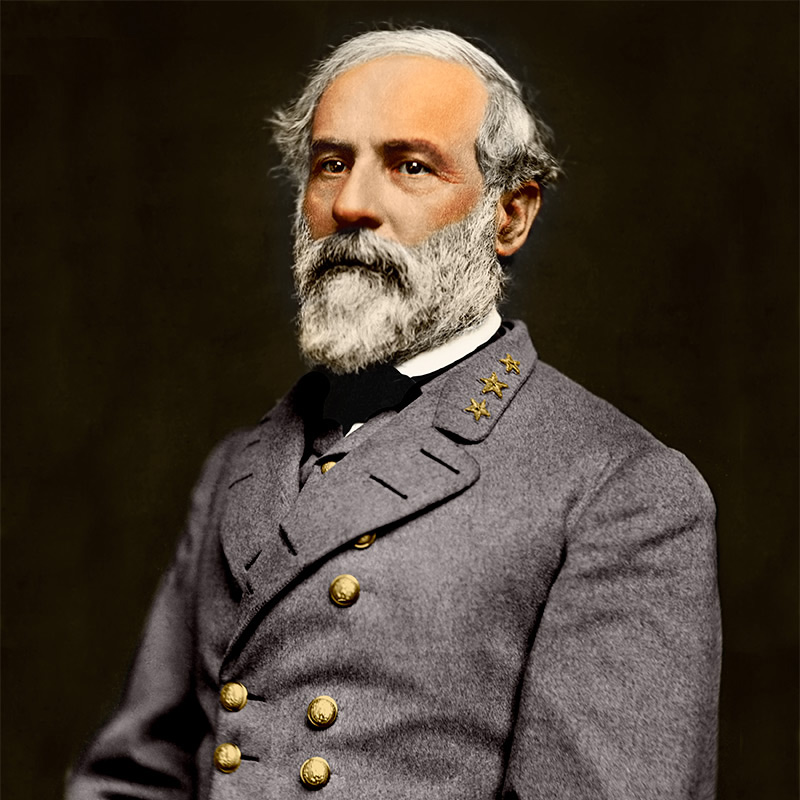

Following the Confederate victory at II Manassas in August of 1862, Robert E. Lee, in command of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, made the controversial decision to move his army into Union territory and take the war to the enemy’s ground. A persistent Southern hope throughout the war centered on making the Northerners so tired of the bloodshed that they would negotiate a peace and end the war. That was one thought President Abraham Lincoln could not and would not countenance.

General Robert E. Lee (1807-1870), commander of the Army of Northern Virginia

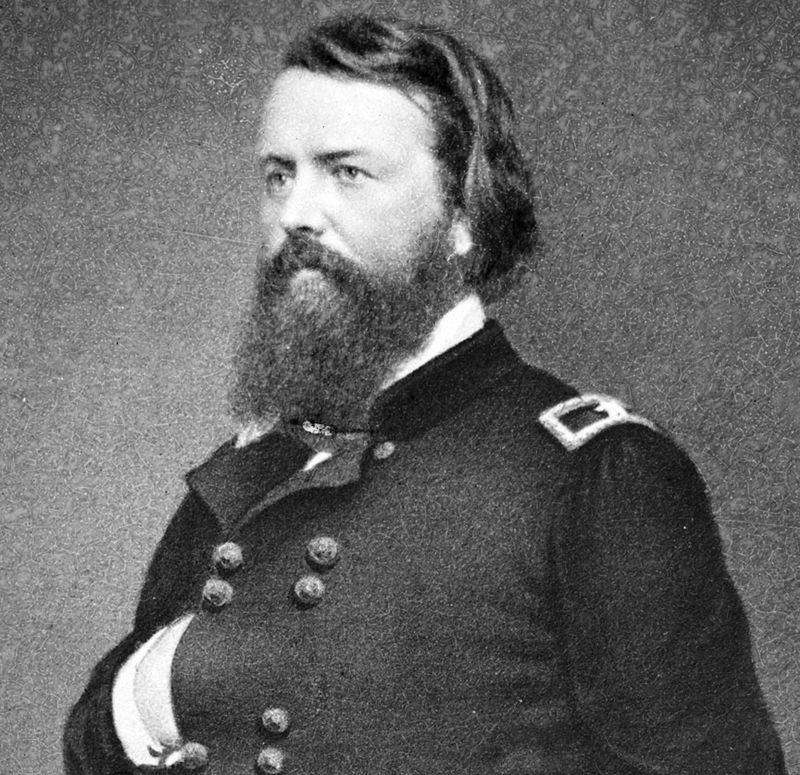

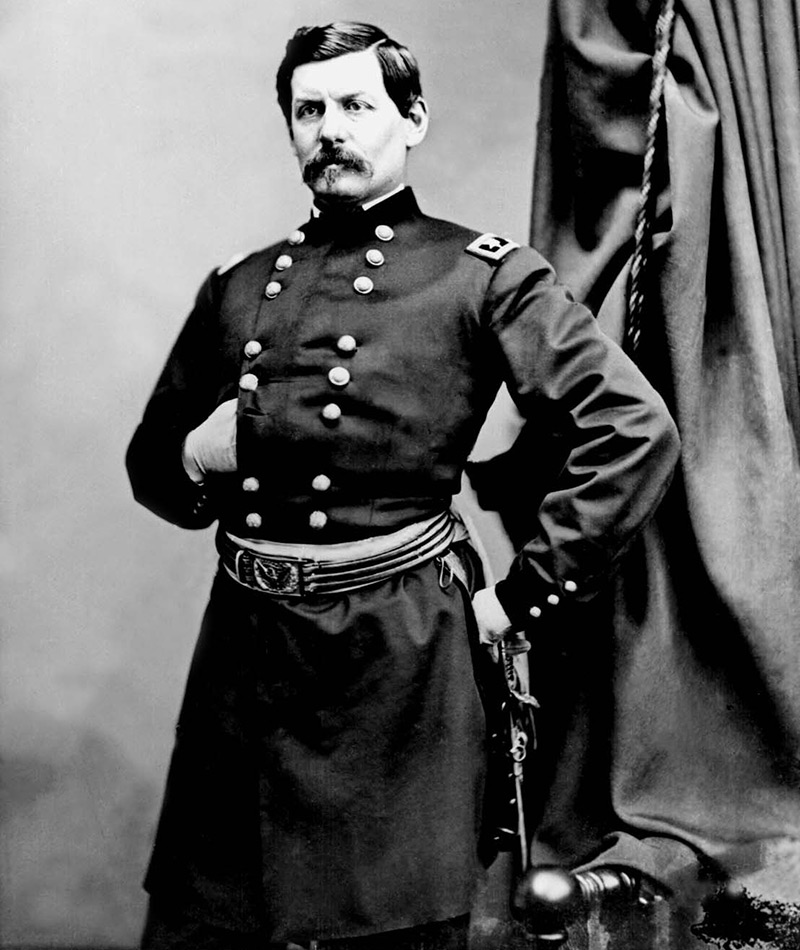

The President’s most recent hand-picked General, John Pope, had failed him at Manassas. He turned once again to George B. McClellan, a man whom Lincoln knew hated him and was a proven failure, though popular with the army itself. General McClellan knew that Lee was somewhere in Western Maryland, and his job was to track him down, bring the Confederates to battle, and put an end to that army. Providence handed McClellan the opportunity to do just that.

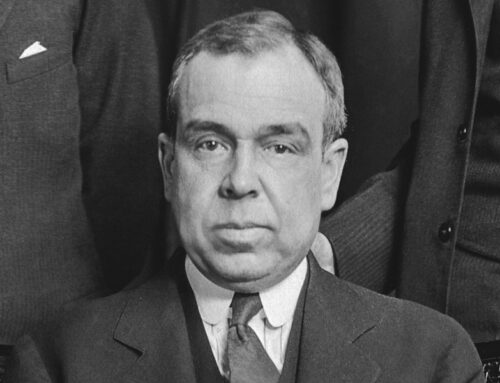

Union General John Pope (1822-1892)

Lee had divided his army into three parts, sending Stonewall Jackson and 13,000 men to capture the Union supply depot at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, defended by a force of about 12,700. General Longstreet and his Corps continued north to Hagerstown, Maryland, and General Lee with the remainder of his forces camped at Sharpsburg along Antietam Creek. The Union Army of the Potomac marched to Frederick, Maryland, the last known location of the Southern Army. While camping in the vicinity, two Yankee soldiers found General Lee’s entire strategic layout written on a General Order and wrapped around three cigars, carelessly dropped by a Confederate general. They rushed the information up the chain of command and McClellan suddenly possessed the opportunity to crush Lee’s army in detail and end the war.

Union General George B. McClellan (1826-1885)

Confederate observers on South Mountain, which screened Sharpsburg from the Northern army, saw the blue host emerge from Frederick and begin its march across South Mountain to destroy the Southern army. The outlying Southern troops were ordered to Sharpsburg, units were placed in the gaps of the mountain to slow down the overwhelming onslaught, and Lee prepared for the battle of his and his nation’s life. The Southern army had its back to the Potomac River, was outnumbered, 38,000 to 87,000 and was hungry and tired. McClellan, whose reputation was one of caution and slowness, did not disappoint, taking two days to get into position, allowing time for the gray-clad invaders to concentrate at Sharpsburg. The stage was set for the greatest effusion of blood in the history of the United States.

Union troops attack Confederate forces at Turner’s Gap during the Battle of South Mountain, three days before the Battle of Antietam

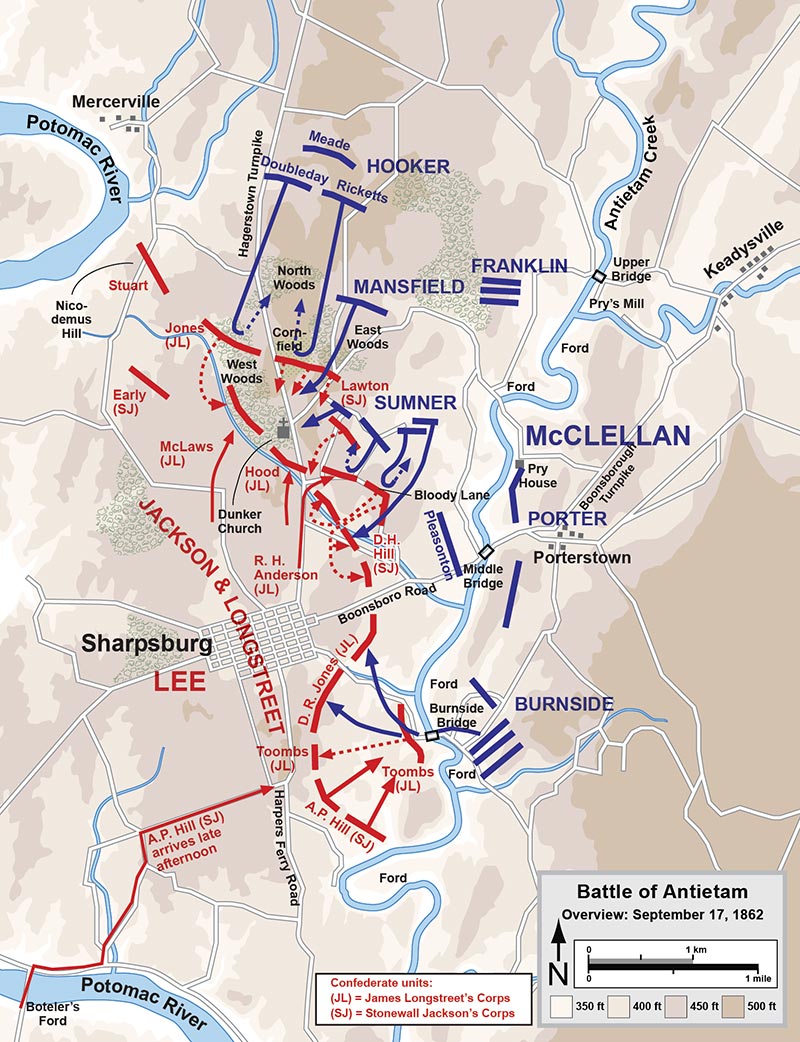

The battle began early in the morning of September 17 as 8,000+ veteran Union infantry advanced up the Hagerstown turnpike against an approximately equal number of Confederates awaiting them along the post and rail fences and open fields of the farms that lay in the path. Most of the men on both sides were veterans and had proven themselves courageous and deadly many times in the past year. Confederate artillery in front and on the right flank of the Union attack opened fire, as did the massed Union artillery across Antietam Creek. The thunder and lightning of the big guns was both deafening and deadly.

Overview of the Battle of Antietam

The first phase of the battle immortalized places called the Dunker Church, the East Woods, Miller’s Cornfield, and the West Woods. After the two armies exhausted themselves, leaving more than 13,000 men on the ground dead and wounded, including two Union Corps commanders, they shifted the fight to “the Sunken Road” later known as the Bloody Lane. Another six or seven thousand fell here, including several generals. The Confederate line bent but did not break.

Dunker Church behind a field of Union and Confederate dead

A monument marks the sunken road, later known as “Bloody Lane”

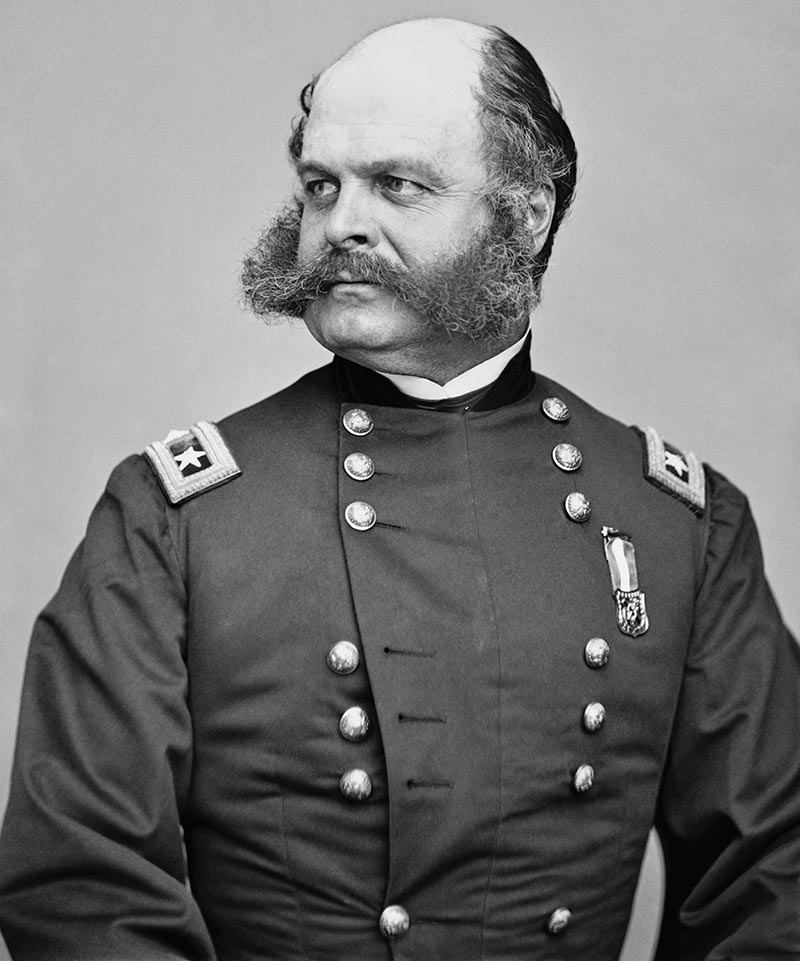

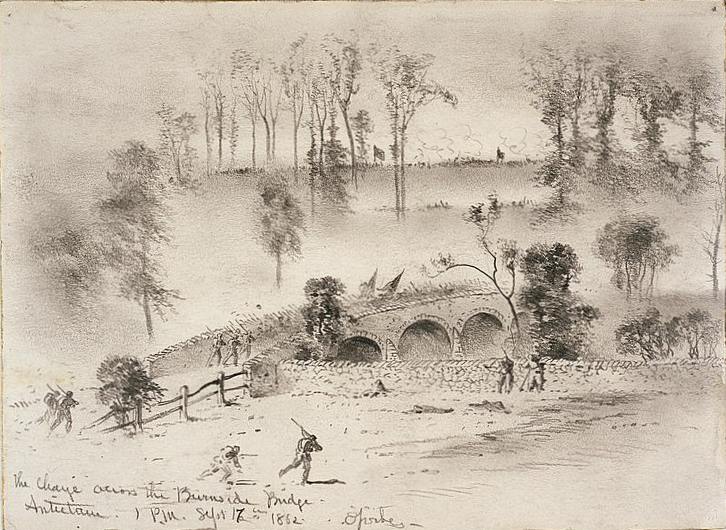

The final phase of the battle pitted some 300+ Georgia infantry defending the Rohrbach Bridge against the entire 9th Corps of some 12,000 men and fifty guns, commanded by General Ambrose P. Burnside, who took three hours to get across the bridge and finally breach the Confederate line. They were struck on the flank by the timely arrival of A.P. Hill’s Light Division who virtually ran to the battlefield after receiving the surrender of the Federal forces at Harper’s Ferry, only 26 miles away. While the Southern wounded were carried to Virginia hospitals, Lee remained in line of battle the next day, daring McClellan to attack. Thinking he was outnumbered, although he had an entire Corps of fresh troops, more than all the survivors of the CSA army, he allowed Lee to slip back to safety during the night. The cost of one day of battle shocked both nations: about 23,000 combined casualties with nearly 4,000 dead on the field. Northern photographers rushed to the battlefield and took dozens of photographs, bringing the grim horror of war home to the civilian population for the first time. The shocking truth of battle stunned the nation.

Union General Ambrose Burnside (1824-1881)

Infantry regiments cross Rohrbach Bridge, later known as Burnside’s Bridge

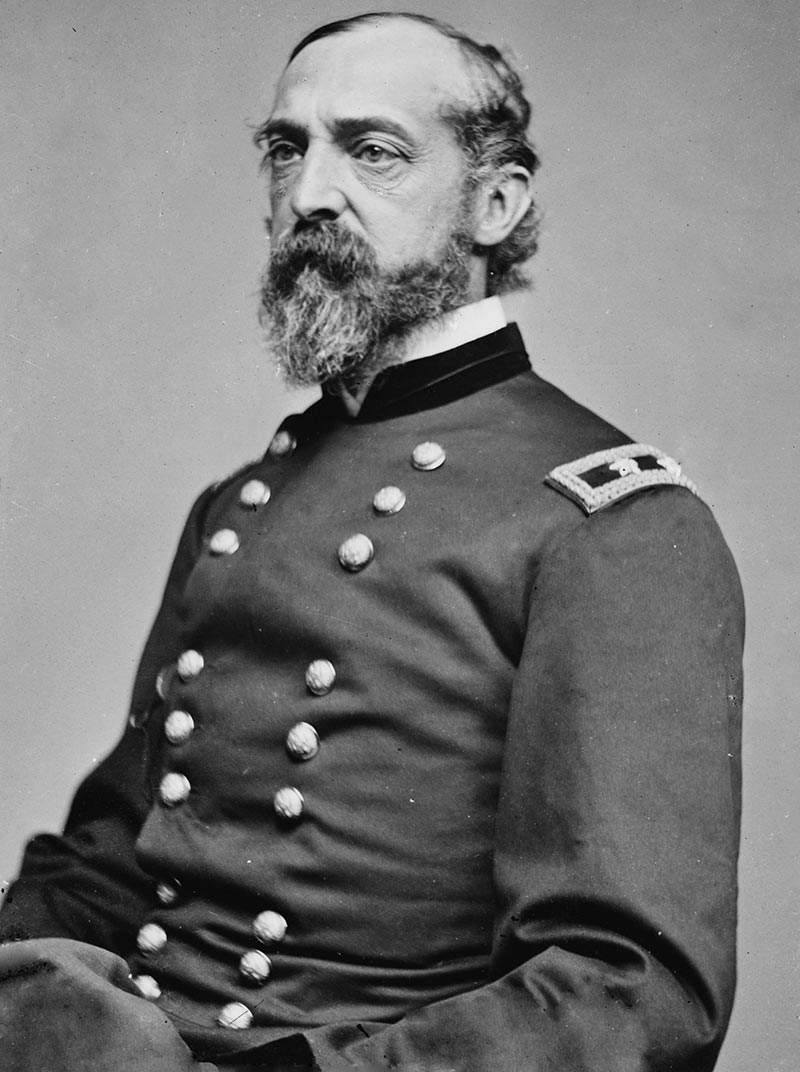

President Lincoln declared Antietam a Union victory and issued the Emancipation Proclamation, adding a new goal to the war—the emancipation of slaves behind the Confederate lines. His move had diplomatic repercussions in England, preventing them forever from recognizing the Confederacy. He also sacked McClellan for not chasing after the retreating Confederates. He replaced him with Ambrose Burnside, who would lead the Union Army to be slaughtered at Fredericksburg, Virginia three months later. As a micro-manager, the President’s ill-starred choices would continue until he brought in George Meade. Lee soon recovered from his losses, won two more huge battles before trying another invasion of the north, the second time paying a visit to another small town, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Union General George Meade (1815-1872)

Image Credits: 1 The Battle of Antietam (Wikipedia.org) 2 General Robert E. Lee (Wikipedia.org) 3 General John Pope (Wikipedia.org) 4 George B. McClellan (Wikipedia.org) 5 Battle Overview Map (Wikipedia.org) 6 Turner’s Gap (Wikipedia.org) 7 Dunker Church (Wikipedia.org) 8 Sunken Road (Wikipedia.org) 9 Ambrose Burnside (Wikipedia.org) 10 Rohrbach Bridge (Wikipedia.org) 11 George Meade (Wikipedia.org)