The Battle of Shiloh, April 6-7, 1862

![]() he month of April being Confederate History Month, at least in Shenandoah County, Virginia, we would do well to remember the battle that shattered the preconceptions of both North and South, as to the cost that the War Between the States could exact. Smaller fights in numerous places around the periphery of the South had already been fought since the first major engagement at Manassas, Virginia. After the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee, and the subsequent capture of Nashville, a little known Ohio-born brigadier from Illinois—Ulysses S. Grant—had emerged as the new hero of the Union.

he month of April being Confederate History Month, at least in Shenandoah County, Virginia, we would do well to remember the battle that shattered the preconceptions of both North and South, as to the cost that the War Between the States could exact. Smaller fights in numerous places around the periphery of the South had already been fought since the first major engagement at Manassas, Virginia. After the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee, and the subsequent capture of Nashville, a little known Ohio-born brigadier from Illinois—Ulysses S. Grant—had emerged as the new hero of the Union.

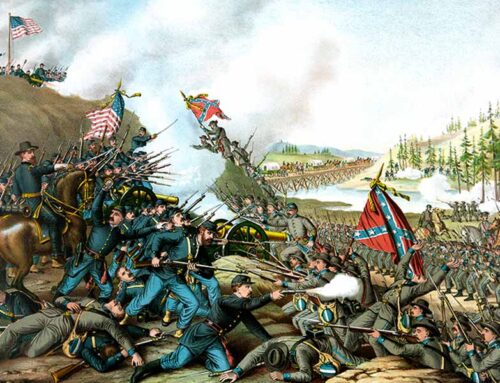

Battle of Shiloh, painting by Thure de Thulstrup, 1888

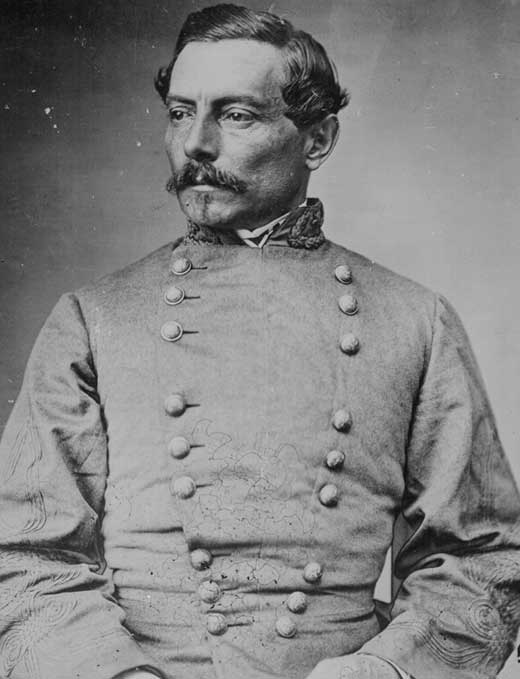

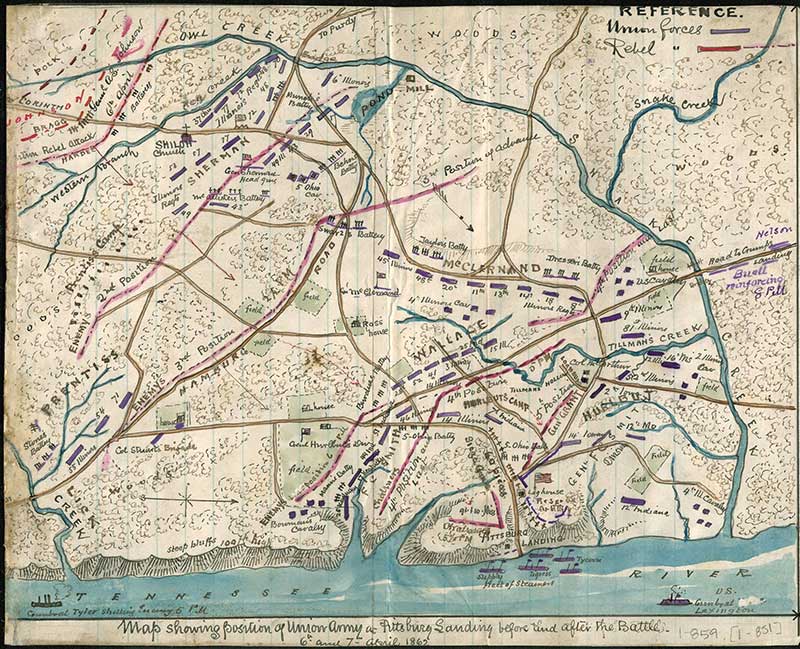

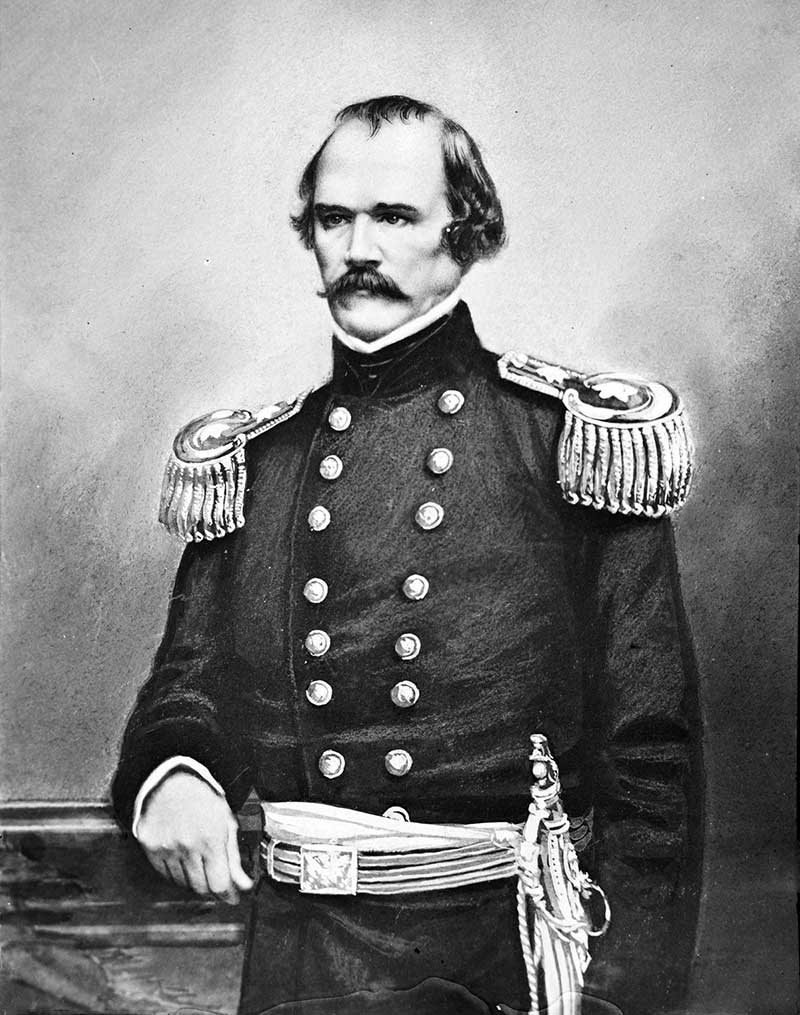

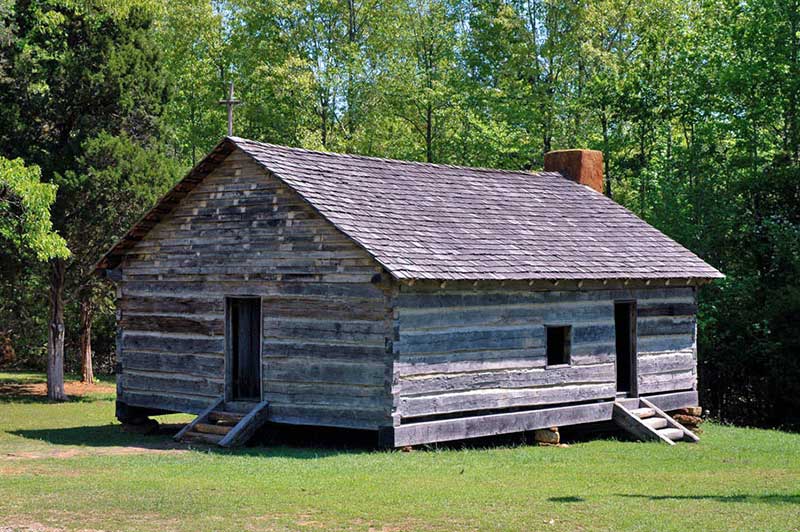

Grant moved his 49,000-man army down the Tennessee River and encamped just north of the Mississippi border at a place called Pittsburg Landing the following month. Spreading more than three miles inland past a little country chapel called Shiloh (meaning “place of peace”), the Union army sprawled in camps awaiting about 18,000 reinforcements on the way from Nashville under General Don Carlos Buell. Following the loss of the forts and the Tennessee capitol, the commander of the Confederate Tennessee Army, Albert Sydney Johnston, concentrated his forces at the rail and road junction of Corinth, Mississippi, about nineteen miles south of the Shiloh Meeting House. Johnston and his second in command, General P.G.T. Beauregard, prepared their 40,000-man force to surprise the unwary blue-coated invaders in the forest and fields where they slept.

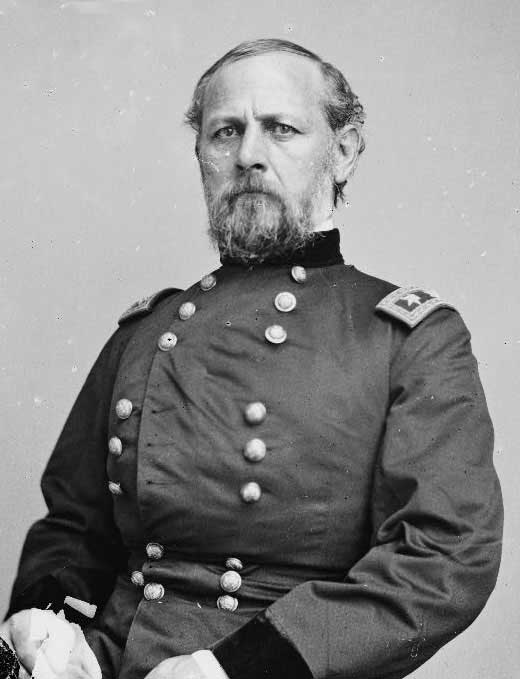

Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885), photographed in 1861

General Don Carlos Buell (1818-1898

General Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (1818-1893)

After an all-night march, the Southern Army lined up to assault the outermost Union troops at dawn on April 6. That day, Johnston had told his officers “tomorrow we will water our horses in the Tennessee River.” He was the highest-ranking Confederate general and the most highly thought of by the government, and his own staff had no doubt that his troops’ dispositions and Southern valor would carry them to victory. Of the seventy-nine regiments in the Confederate line of battle, only 14 had any previous combat experience. The Federal Army, about equal in number, had the advantage in numbers of veteran soldiers, but were unaware of the coming attack, and were mostly asleep when the assault began. The attack proved to be a big surprise. However, man proposes but God disposes.

A map of the Shiloh battlefield, hand drawn in 1865

The Confederate staff officers had little or no experience at war, and to them fell the proper disposition of the soaked and exhausted troops, streaming up the two narrow and foot-deep muddy country roads from Corinth to Pittsburg Landing. Federals on the outer picket lines exchanged fire with Confederate cavalry and infantry and reported to the Division commander William T. Sherman that the Rebel Army was hovering around the Union position. He ignored their warnings. General Johnston had his last dispatch read to the Southern troops along the three-mile long battle front:

I have put you in motion to offer battle to the invaders of your country, with the resolution and disciplined valor becoming men, fighting, as you are, for all worth living or dying for. You can but march to a decisive victory over agrarian mercenaries, sent to subjugate and dispoil you of your liberties, property and honor.

Remember the precious stake involved, remember the defense of your mothers, your wives, your sisters, and your children, on the result. Remember the fair, broad, abounding lands, the happy homes that will be desolated by your defeat. The eyes and hopes of 8,000,000 people rest upon you. You are expected to show yourselves worthy of your race and lineage, worthy of the women of the South, whose noble devotion in this war has never been exceeded in any time. With such incentives to brave deed, and with the trust that God is with us, your General will lead you confidently to the combat, assured of success. (Signed)

A.S. JOHNSTON, General Commanding.

General Albert Sidney Johnston (1803-1862)

A reproduction of Shiloh Church on the Shiloh Battlefield

As the attack rolled over the outer defenses, General Grant, always unflustered, ordered up reinforcements, especially Major General Buell’s 18,000 men beginning to arrive and ready for deployment the following day. The battle, like every huge, significant engagement of that war, gave to history a small lexicon of especially important or bloody places on the field. Bloody Pond, The Hornet’s Nest, the Peach Orchard, and Shiloh Church took their place more than a year before Little Round Top, Seminary Ridge, Cemetery Ridge, and Devil’s Den did at Gettysburg. And there were providences aplenty that defined the direction the battle would go. One of the most important events that may have defined the rest of the first day was the mortal wounding of General Johnston who received three wounds from shell fragments and, without an immediate realization of the seriousness of his condition, bled to death when his physician could not be found. The surgeon was on another part of the field treating wounded enemy soldiers.

Monument to General Johnston on the Shiloh Battlefield

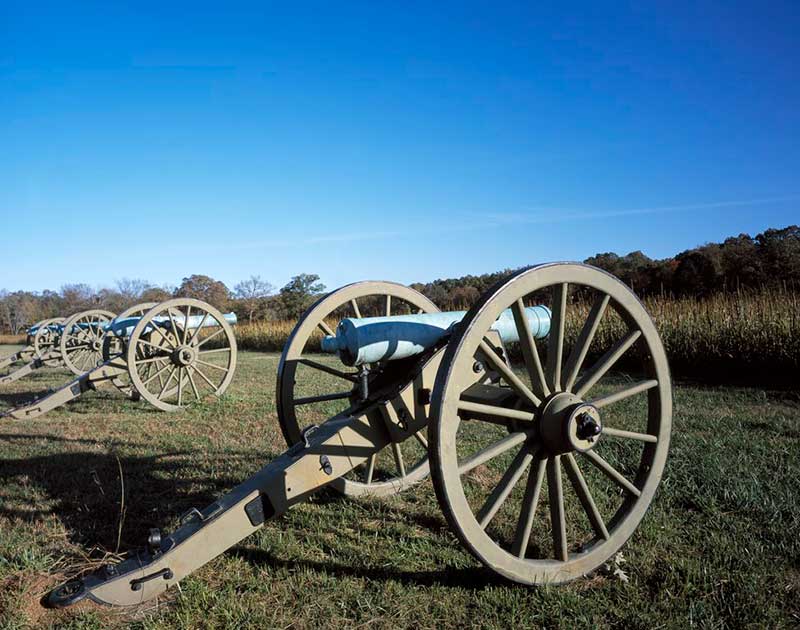

Union artillery facing the Peach Orchard, Shiloh Battlefield

The Sunken Road, Shiloh Battlefield

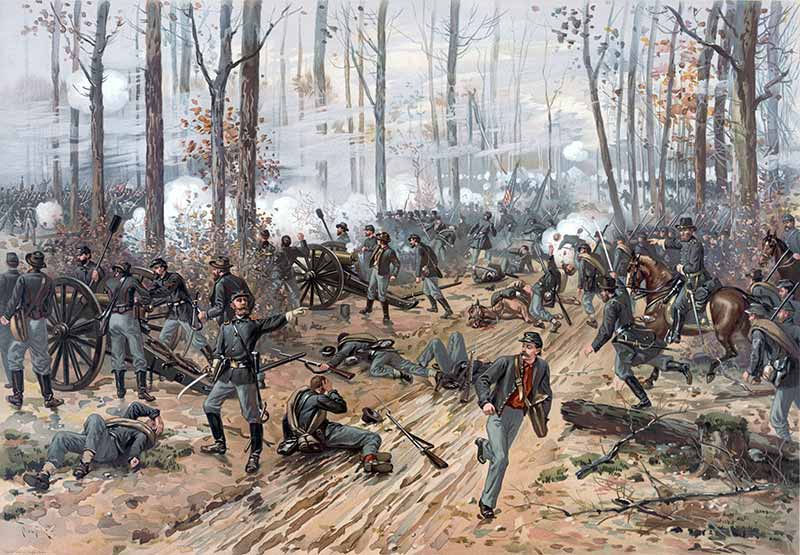

One of General Sherman’s subordinate generals made a heroic and almost suicidal stand in a copse of woods known forever after as the Sunken Road and the Hornets’ Nest for all the bullets that buzzed through the air, and for the stinging defense that threw back repeated Confederate attacks. The stand at the Hornets’ Nest gave the Union commanders time to shore up their broken lines and establish defenses that prevented their overthrow. As at Fort Donelson in the past and successive battles hereafter, Ulysses S. Grant lost the first day of battle, refused to give up or retreat, and won the contest on the second day. In the case of Shiloh, he received huge reinforcements during the night and counter-attacked to victory the next day, April 7.

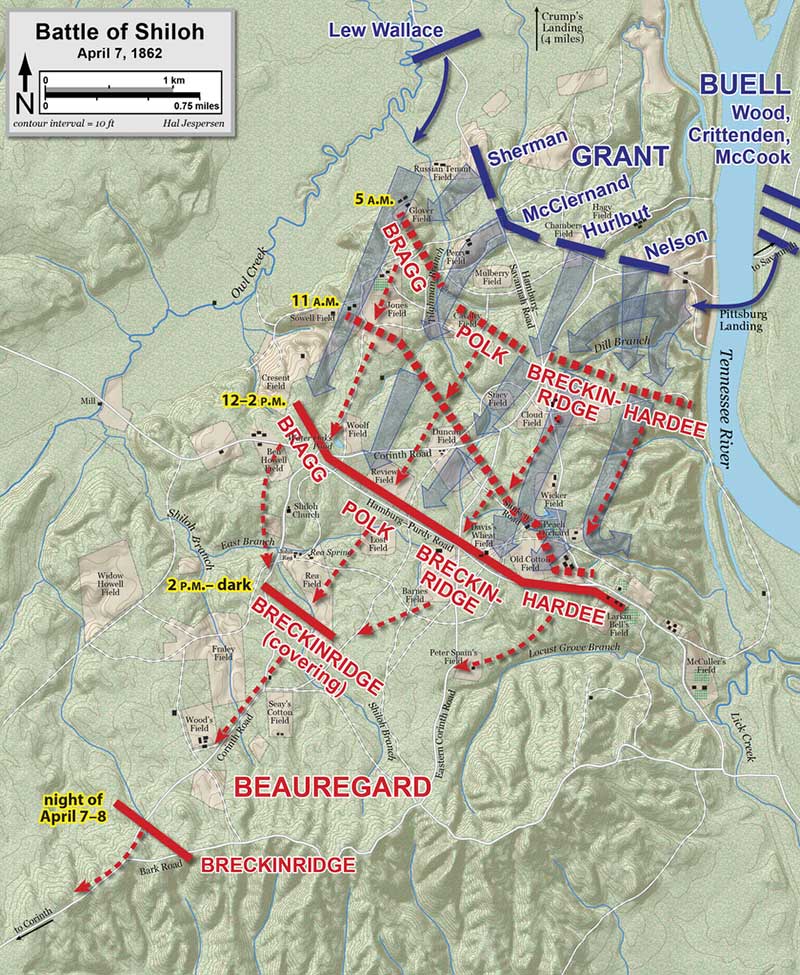

Overview of the second day of the Battle of Shiloh, April 7, 1862

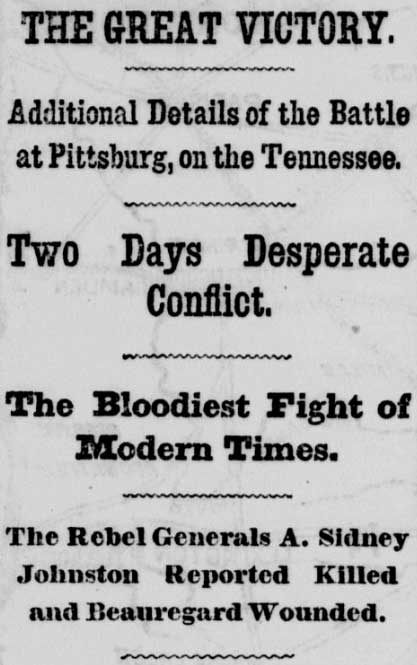

Nearly 24,000 men fell on those two days, more than 10,700 Confederates and 13,000 plus Union soldiers. Shiloh and Chickamauga have vied ever since as “the bloodiest two-day battle in American history.” Confederate reinforcements never arrived and their army withdrew back to Corinth the evening of the second day, leaving the Federal forces in command of the battlefield. The casualty lists absolutely shocked both countries—nothing of its magnitude had ever occurred on the continent in history, and both sides were put on notice that the cost in blood and treasure, and the duration of the war, would exceed all previous expectations. Along with a severe blow to Confederate morale with the loss of General Johnston and the retreat of the gray army, General Grant once more became the talk of the nation as the unbeatable and immovable general, although one who had been surprised by his enemy and sacrificed the lives of multiple thousands of young men on the altar of the nation. The invasion continued for more than two more years and the newfound hope in Grant was justified by those who desired preservation of the new imperial Union.

The New York Herald reporting on the Battle of Shiloh on April 10, 1862

A portion of Shiloh National Cemetery, final resting place of 3,584 Union dead (of whom 2,357 are unknown) and 2 Confederate dead—an unknown number of Confederate dead are buried in mass graves throughout the park

- Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862, by O. Edward Cunningham (2007)

Image Credits: 1 Battle of Shiloh painting (wikipedia.org) 2 General Grant (wikipedia.org) 3 General Buell (wikipedia.org) 4 General Beauregard (wikipedia.org) 5 General Johnston (wikipedia.org) 6 Battlefield Map (wikipedia.org) 7 Shiloh Church (wikipedia.org) 8 Johnston Monument (wikipedia.org) 9 Peach Orchard (wikipedia.org) 10 Sunken Road (wikipedia.org) 11 Battle Overview (wikipedia.org) 12 New York Herald (wikipedia.org) 13 Shiloh National Cemetery (wikipedia.org)