The Battle of Fort Sumter Begins, April 12, 1861

pril 12, 1861 the United States Navy tried to resupply Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. The State of South Carolina claimed that ownership of the fort had defaulted to their state when the Federal government decided not to garrison the place over the previous several years. After a clandestine re-occupation of the bastion by Union troops from Fort Moultrie, the Lincoln government was put on notice that a resupply would be considered an act of war, and responded to accordingly. And so the first shots fired in anger after the creation of the new nation of the Confederate States, forever linked Fort Sumter with the beginning of the American “Civil War.”

pril 12, 1861 the United States Navy tried to resupply Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. The State of South Carolina claimed that ownership of the fort had defaulted to their state when the Federal government decided not to garrison the place over the previous several years. After a clandestine re-occupation of the bastion by Union troops from Fort Moultrie, the Lincoln government was put on notice that a resupply would be considered an act of war, and responded to accordingly. And so the first shots fired in anger after the creation of the new nation of the Confederate States, forever linked Fort Sumter with the beginning of the American “Civil War.”

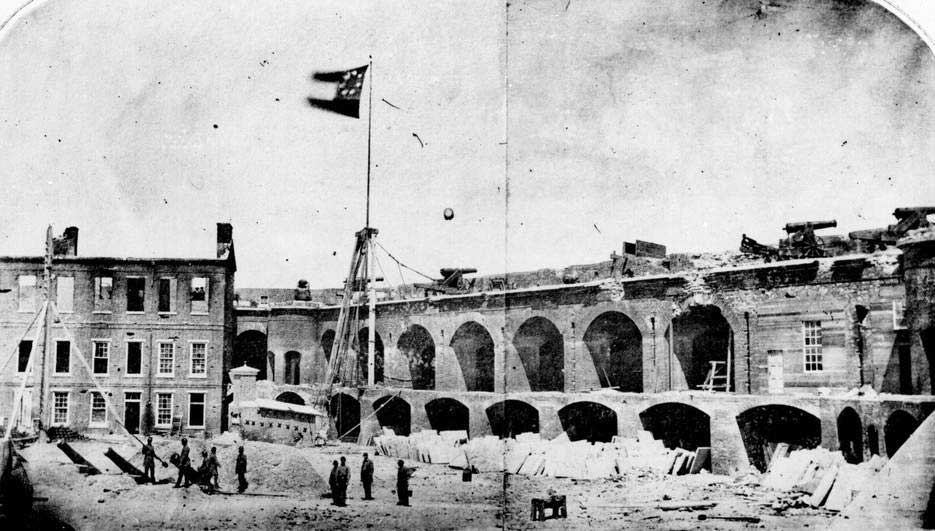

Fort Sumter, Charleston Harbor, South Carolina as photographed in 1861

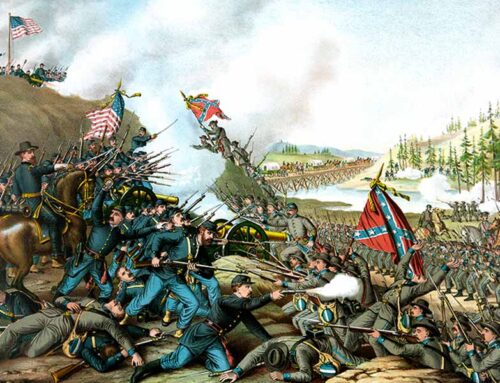

Four years later on April 9, 1865, with both countries having collectively suffered the loss of more than 700,000 dead and a half million wounded, the major army of the Southern Confederacy, led by General Robert E. Lee, surrendered to the Union forces of General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, thus, for all practical purposes, ending the War for Southern Independence. Several more battles were to be fought by other armies still in the field resisting the behemoth Union war machine, but the inevitability of full unconditional surrender by all the states “in rebellion” was grasped by all. American history changed forever; we live with the consequences to this day.

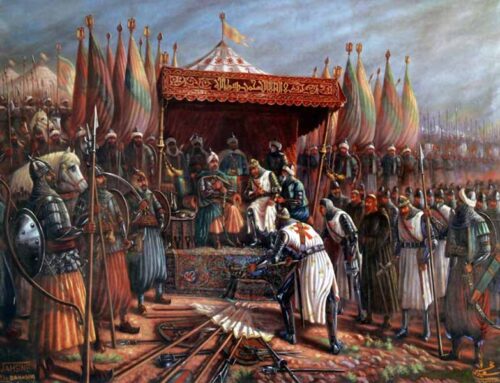

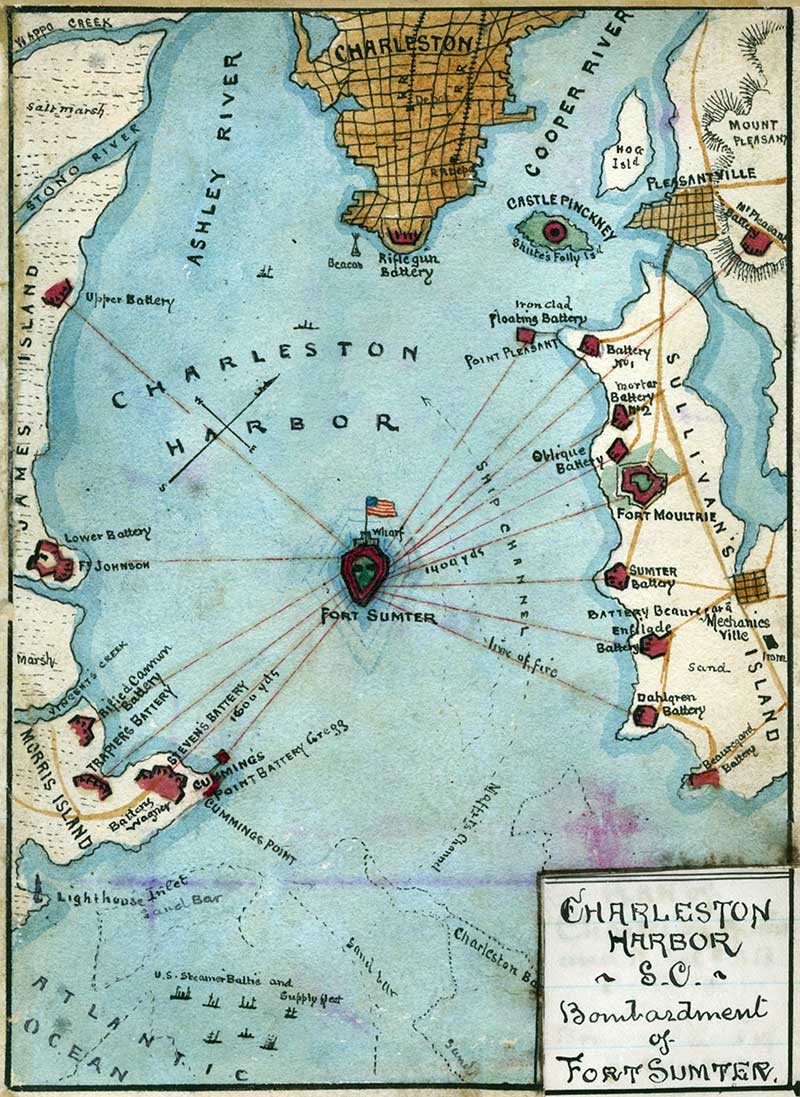

Regional view of Charleston Harbor showing the city of Charleston on the Ashley and Cooper rivers, Castle Pinckney on Shute’s Folly Island, Pleasantville and Mt. Pleasant Battery, Mechanicsville and batteries on Sullivan’s Island, and the Morris and James island batteries, and their distances from Fort Sumter

United States Army engineers constructed Fort Sumter during the War of 1812 as part of a chain of such forts and shore batteries to protect coastal harbors of the United States. Seventy thousand tons of granite were brought by sea from New England and piled on a sandbar in Charleston Harbor to form the two and a half acre base for the three-story brick pentagonal fortress. For a variety of reasons, the fort was never completed or strongly garrisoned, though the exterior was completed enough for use. With defense expenditure cutbacks and no serious threats to the United States, Sumter in 1860 was occupied only by a caretaker and about one hundred fifty workmen.

Officers of U.S. Garrison, Fort Sumter, April, 1861—front row, left to right: Capt. A. Doubleday, Major R. Anderson, Asst. Secretary. S. W. Crawford, Capt. J. S. Foster; back row, left to right: Capt. T. Seymour, Lt. G. W. Snyder, Lt. J. C. Davis, Lt. R. K. Meade, Capt. T. Talbot

South Carolina seceded from the Union on December 20, 1860, and state militias began assembling around Charleston with an eye on the Federal military post at Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island. The garrison commander, Major Robert Anderson, decided to quietly move his men and their families in the middle of the night on the day after Christmas to the more substantial and better armed Fort Sumter in the middle of the harbor. He immediately set about fortifying gun positions and closing unused embrasures. The furious Governor Pickens of South Carolina demanded that President Buchanan order Major Anderson to abandon the fort since it now belonged to the state and threatened the city from its position in the harbor. Major Anderson refused to surrender and awaited instructions from Washington. Anticipating a possible attempt by South Carolina troops to attack Fort Sumter, Union Lieutenant Davis said, in looking at the wooden doorway into the fort “Trust in Providence, and the main gate, after it’s bricked up.”

Francis Wilkinson Pickens (1807-1869), Governor of South Carolina at the time of Secession and the Battle of Fort Sumter

Painting depicting ‘Major Anderson Raising the Flag on the Morning of His Taking Possession of Fort Sumter, December 27, 1860’

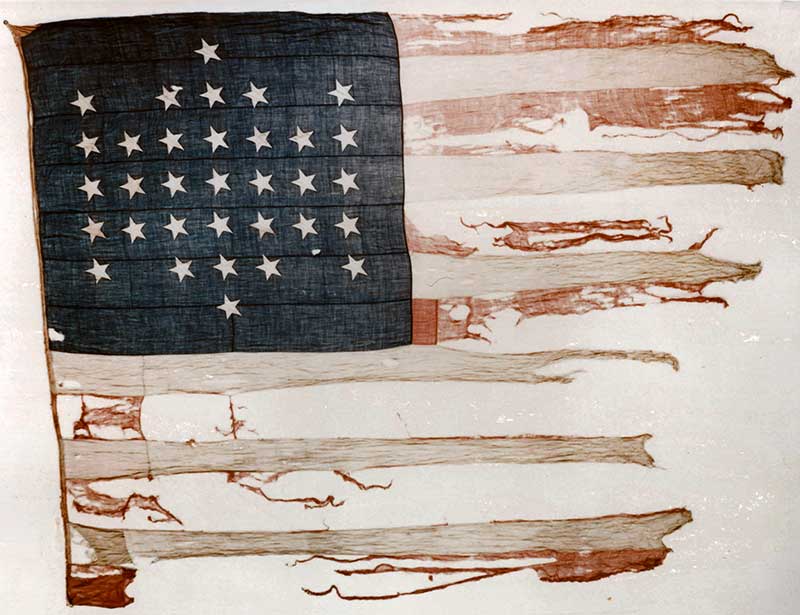

Anderson had about eighty men to defend a fort built to be manned by a thousand. The entire garrison, the workmen (mostly Irishmen), and their families assembled on the parade ground and took a knee as the chaplain prayed that the flag about to be raised would soon fly again over a reunited nation. In the coming events, the garrison flag (20 feet by 36 feet in size) and the storm flag (10 by 20 feet) would play an important role.

What remains of the garrison flag flown over Fort Sumter during the bombardment, now displayed at the Fort Sumter Visitor Center in Charleston, SC

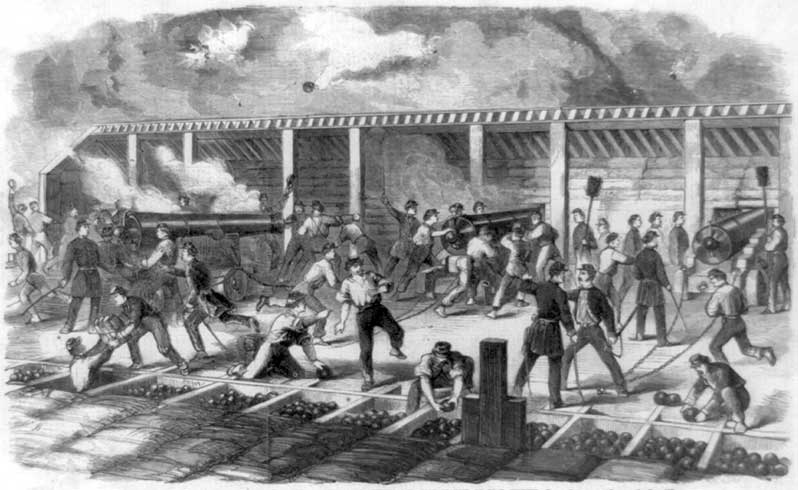

Sketch by an officer portraying the scene on the floating battery in Charleston Harbor, S.C., during the bombardment of Fort Sumter

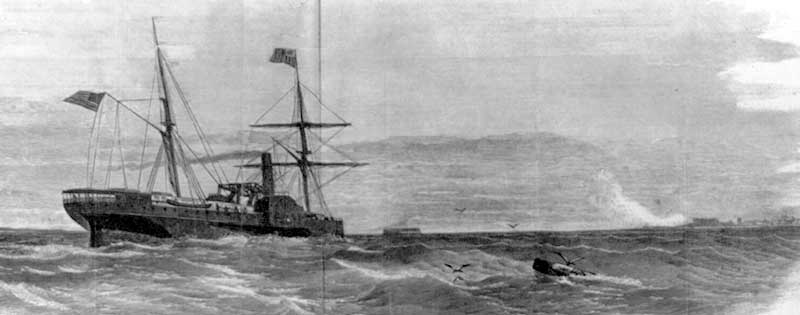

On January 9, nine cadets from the Citadel fired a cannon at The Star of the West, sent to resupply the fort. On February 1 the women and children were sent ashore. In early March, General P.G.T. Beauregard, a close pre-war friend of Major Anderson, arrived from the Confederate government in Montgomery, Alabama, to take charge of the defense of Charleston and the acquisition of Fort Sumter. He immediately sent a box of cigars out to Major Anderson and demanded he surrender the post.

The steamship The Star of the West with reinforcements for Major Anderson and Fort Sumter, under fire from Confederate batteries on Morris Island and Fort Moultrie

The President-elect kept his own counsel in Springfield, Illinois awaiting the action of President Buchanan, but made it clear in private correspondence that he would not only keep the fort, but would re-take it if the current chief executive gave it to the Confederates. As the March 4 inauguration approached, Lincoln’s comments remained somewhat ambiguous although he pronounced two non-negotiables: 1. No state could lawfully secede and 2. “The power confided in me will be used to hold, occupy and possess the property and places belonging to the government.”

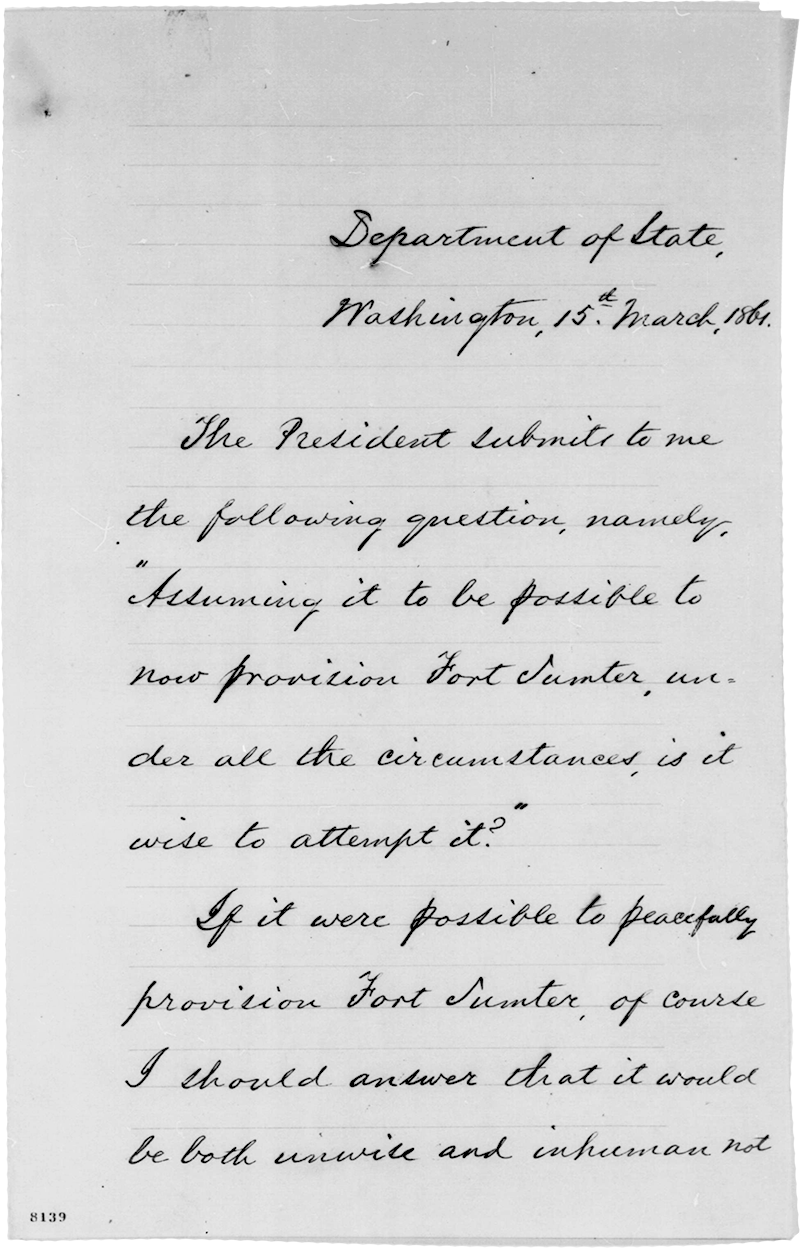

Nonetheless, the commander of the American Army, Winfield Scott, Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William Seward, and most of the President’s cabinet, including the Secretary of War, believed the Fort should be evacuated before the garrison ran out of food and were forced to surrender, arguing that trying to re-provision would likely cause war. Two emissaries from President Lincoln to Charleston confirmed South Carolina’s will to fight and the need to evacuate the fort before it came to that. While the government dithered, the Confederates constructed batteries facing the fort and the harbor entrance. Between March 30 and April 6 Captain Gustavus Fox, following President Lincoln’s express secret orders, assembled a relief squadron, “a little flotilla,” and set sail to rescue Fort Sumter.

A portion of a letter from Secretary of State William H. Seward to President Abraham Lincoln concerning the advisability of reprovisioning Fort Sumter, March 15, 1861

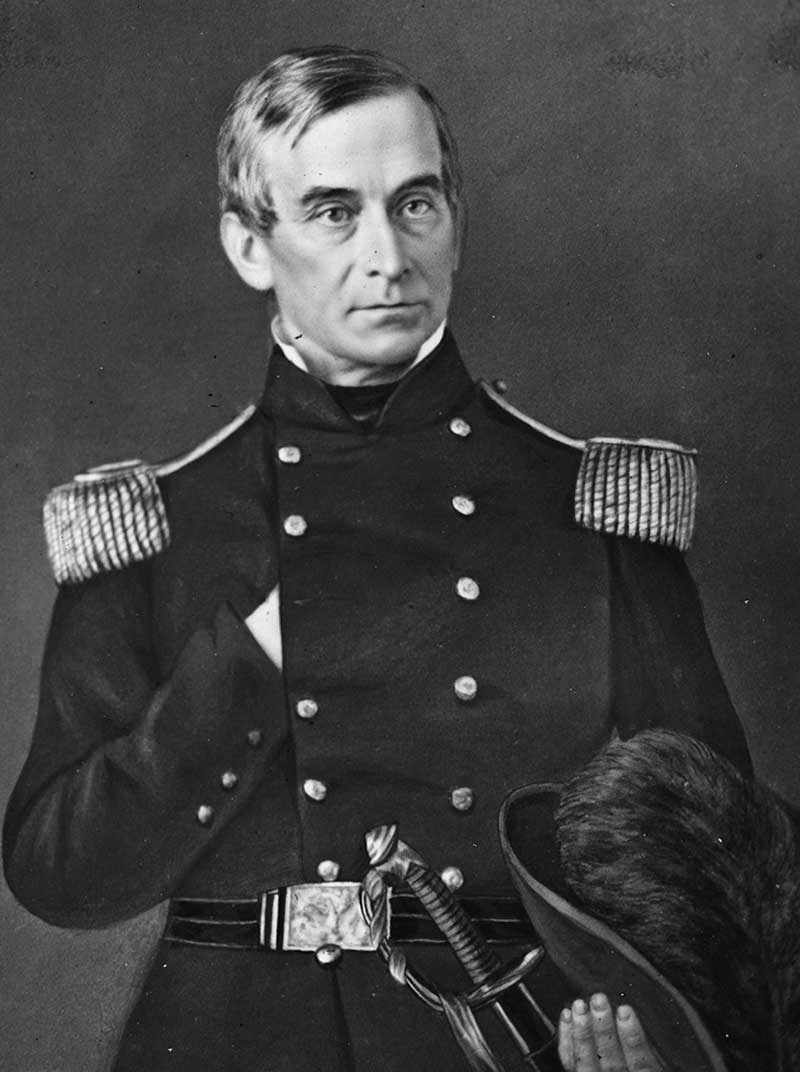

Major Robert Anderson (1805-1871)

General Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (1818-1893)

Major Anderson was stunned to learn from an official letter that a relief expedition was on the way. He had worked so hard to keep the peace and prevent a war from breaking out and knew that the appearance of Union warships would precipitate war. President Jefferson Davis was informed of the coming relief expedition and ordered General Beauregard to insist Major Anderson evacuate the fort. On April 11, three representatives of the CSA government delivered the ultimatum. Ever the gentleman, Anderson thanked Beauregard in writing “for the fair, manly, and courteous terms,” but rejected the offer. The Confederate artillerists crewing the forty-three guns ringing Fort Sumter at Fort Moultrie, James Island, and in the harbor opened fire at 4:30 A.M., April 12, 1861. The War was on in earnest.

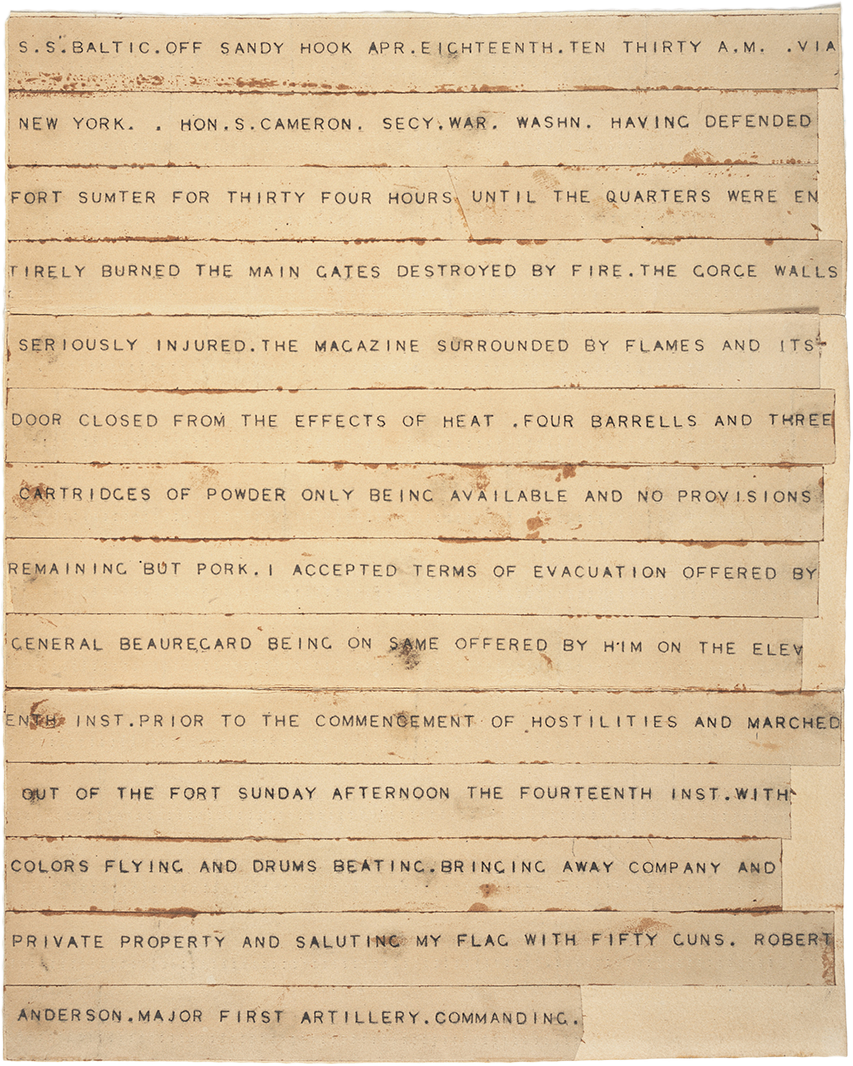

Telegram sent by Major Robert Anderson at 10:30am, April 18, 1861, announcing the surrender of Forst Sumter to confederate General Beauregard

Fort Sumter as photographed on April 15, 1861, after the siege

- For further reading, the best book on the subject is Allegiance: Fort Sumter, Charleston, and the Beginning of the Civil War by David Detzer (2001).

Image Credits: 1 Fort Sumter, before (wikipedia.org) 2 Map of Charleston Harbor, 1861 (wikipedia.org) 3 Officers of Fort Sumter (wikipedia.org) 4 Governor Pickens (wikipedia.org) 5 Raising the Flag (wikipedia.org) 6 Remains of the Garrison Flag (wikipedia.org) 7 Battle Scene (wikipedia.org) 8 Steamship Star of the West (wikipedia.org) 9 Letter from Seward to Lincoln (wikipedia.org) 10 Major Anderson (wikipedia.org) 11 General Beauregard (wikipedia.org) 12 Telegram (wikipedia.org) 13 Fort Sumter, after (wikipedia.org)