“If the thief is caught while breaking in and is struck so that he dies, there will be no bloodguiltiness on his account.” —Exodus 22:2

Paul Revere’s Ride, April 18, 1775

![]() here are several famous horseback rides in American history, not counting at racetracks. Delegate Caesar Rodney made a midnight ride from Delaware to Philadelphia, arriving just in time to vote Delaware into the United States at the Continental Congress in 1776. In 1781, six-foot-four, 220-pound Jack Jouett—a Huguenot descendant of French aristocrats, and an ardent Virginia patriot—galloped through the night for forty miles to warn Governor Thomas Jefferson and the Virginia legislature that British troops under Banastre Tarleton were marching to Charlottesville to capture the lot of them. The most famous ride of all, because of a poem published in 1861 by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, belongs to silversmith Paul Revere, also the descendant of Huguenot exiles in America.

here are several famous horseback rides in American history, not counting at racetracks. Delegate Caesar Rodney made a midnight ride from Delaware to Philadelphia, arriving just in time to vote Delaware into the United States at the Continental Congress in 1776. In 1781, six-foot-four, 220-pound Jack Jouett—a Huguenot descendant of French aristocrats, and an ardent Virginia patriot—galloped through the night for forty miles to warn Governor Thomas Jefferson and the Virginia legislature that British troops under Banastre Tarleton were marching to Charlottesville to capture the lot of them. The most famous ride of all, because of a poem published in 1861 by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, belongs to silversmith Paul Revere, also the descendant of Huguenot exiles in America.

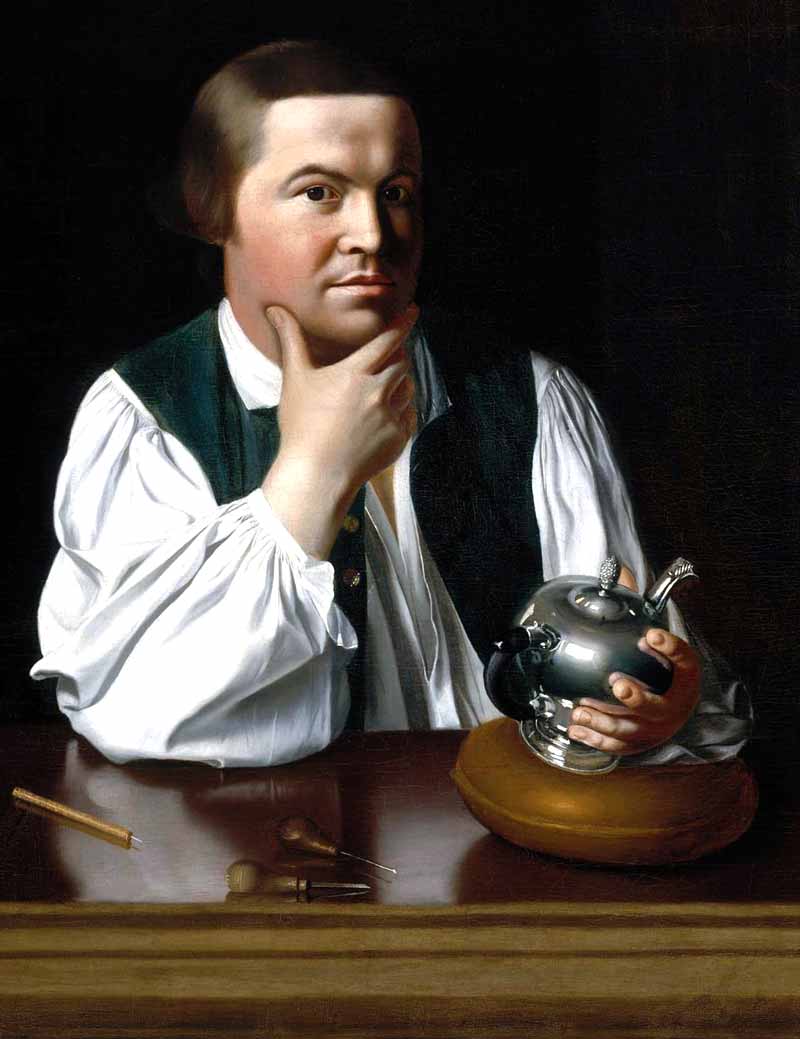

Paul Revere (1734-1818) was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, Sons of Liberty member, and Patriot, best known for his famous midnight ride

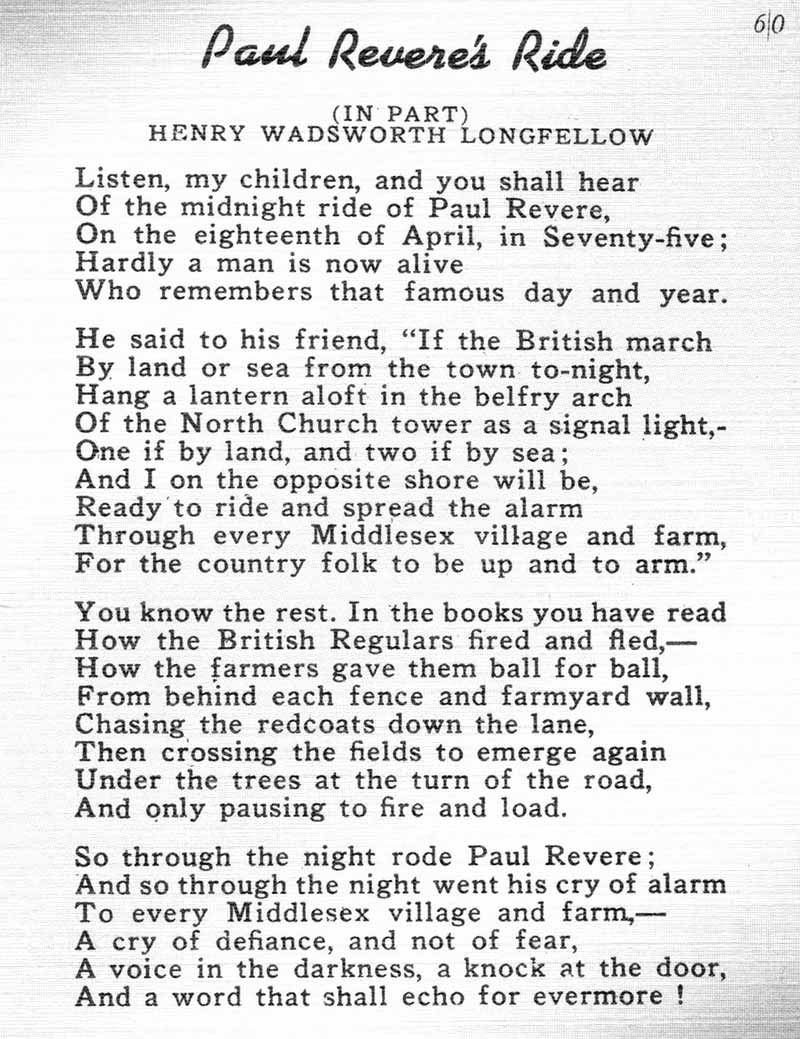

A portion of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, immortalizing Revere’s midnight ride

By 1775, the city of Boston, Massachusetts was under occupations by red-coated British soldiers. People of that city had been resisting the payment of taxes and had committed violence against government agents and English soldiers in the streets. They dumped tea in the harbor, made speeches against the Crown and organized a resistance movement through local militias and committees of correspondence, and sent representatives to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Parliament passed a number of Acts shutting down the Massachusetts government, closing the port, and quartering soldiers in civilian homes. American spies, from housemaids to businessmen, kept up a flow of information to the colonial leaders.

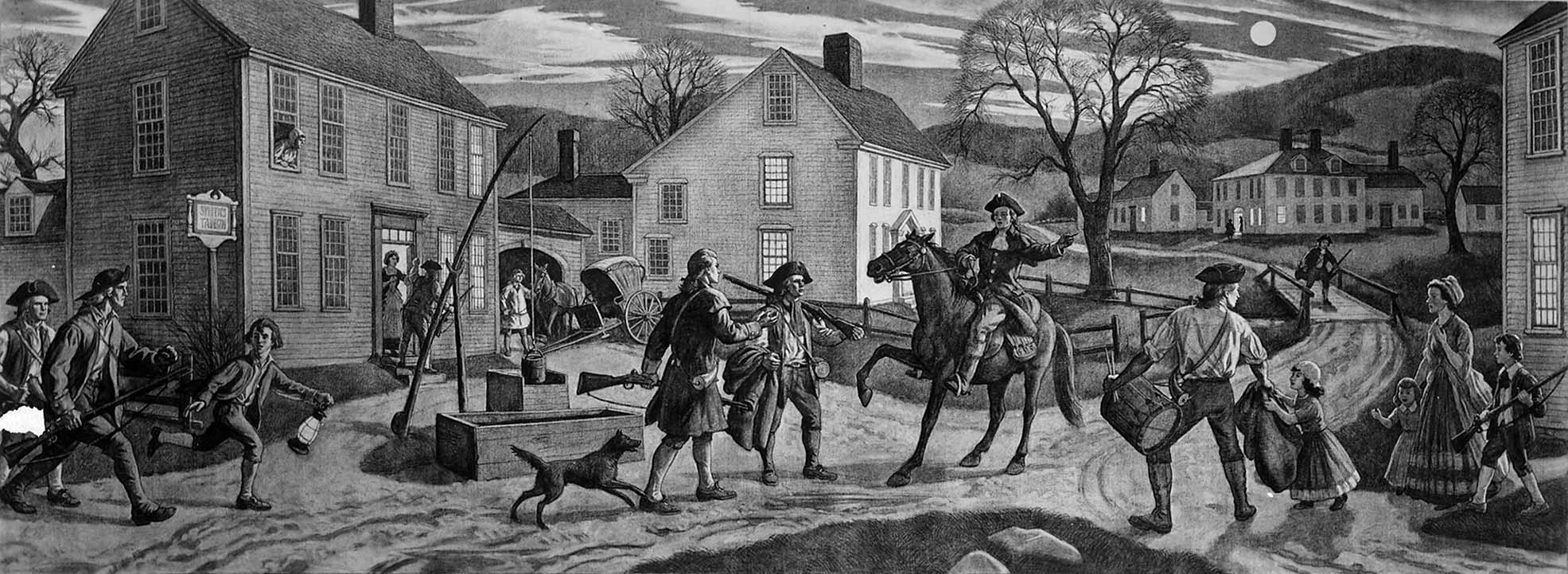

A depiction of Paul Revere riding through and rousing a village along his route

Orders were executed to arrest certain colonial radicals like Samuel Adams and John Hancock, and steal the “military stores” of artillery and gunpowder stocks in villages surrounding Boston. A military expedition was assembled by the British leaders to march through the night to grab the above men and supplies in Lexington and Concord on April 18, 1775.

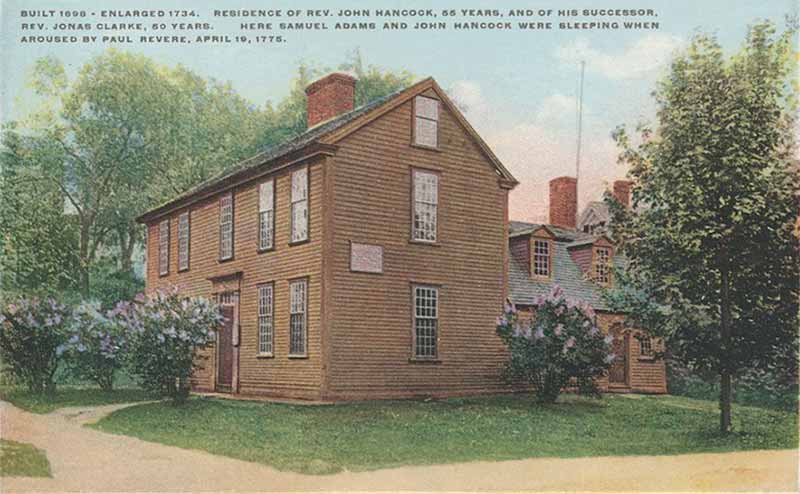

An early 1900s postcard depicting the Hancock-Clarke House in Lexington, Massachusetts where John Hancock and Samuel Adams were staying when Revere rode there to rouse and warn them to flee the coming British troops, intent on their capture

Paul Revere, a highly respected local silversmith and a friend to all, spent time with the British officers, gleaning information from careless talk. Intelligence data also came to him from his clandestine sources. When British General Thomas Gage appointed Lt. Colonel Francis Smith (whom some subordinates described as “fat, slow, stupid, and self-indulgent”) to assemble the strike force, Paul Revere, William Dawes, and an unknown number of other riders prepared to ride out and alert the countryside to the threat.

The Paul Revere house—located at 19 North Square, Boston, Massachusetts—was built in 1680 and served as Revere’s home during the period of the American War for Independence

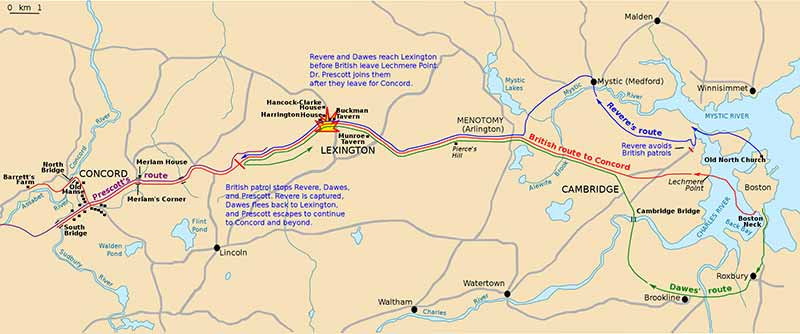

Revere ordered lanterns lit and signals sent from the tower of the Old North Church in Boston. Two friends rowed him across the Charles River to take to the roads of Middlesex County and raise the countryside. Deacon John Larking loaned him his best horse, Brown Beauty, “a joy to ride,” and Revere headed up the road toward Lexington. Spotting two British officers in ambush, Revere turned around and headed full-speed up another road, the enemy in hot pursuit. They could not catch Brown Beauty. Thus, providentially, Revere was forced to take a longer route to Lexington and avoided all the other traps set for him. After warning Adams and Hancock a little past midnight at the town parsonage of Jonas Clarke (and his twelve children) that the British regulars were on the way, Revere headed out for Concord, where the military stores were hidden. He was accompanied by William Dawes and Dr. Samuel Prescott, after a brief stop at the nearby Buckman tavern. They raised the militias in every town they encountered and individual houses as they appeared. Other riders fanned out, and before the next evening multiple thousands of armed men and boys were poaching the redcoats.

One of the signal lanterns used to alert Revere to the route of the British

Old North Church provides the backdrop to a statue of Revere in Boston, Massachusetts

About halfway to Concord, the three patriots were ambushed by four mounted British regulars, soon joined by six more. Doctor Prescott, knowing the backroads and trails, got safely away. The soldiers grabbed Paul Revere, however, and in the confusion Dawes also escaped (although shortly thereafter was thrown by his horse and forced to walk back to Boston).

Map depicting the routes of the British troops (shown in red), Paul Revere (blue), William Dawes (green), and Samuel Prescott (purple) on the night of April 18, 1775

Revere told the patrol about everything that was happening and that they themselves were in danger of being killed by local militia since the alarm had been raised. They abused him with words and took the reins of his horse so he could not escape, as they rode back toward Lexington. Revere kept up his psychological warfare through constant conversation, and his British captors decided to save their own skins after hearing shots fired in Lexington (the militia had fired a volley into the air to clear their barrels); they released the prisoner and galloped toward safety. Revere returned to Lexington around 3:00am and found Hancock and Adams still at the parsonage! The silversmith ran to the tavern and, with help, carried Hancock’s trunk full of important documents out to be transported with the two patriot leaders into the woods. As they drew away from Lexington, they heard a shot, then volleys of shots from the town. They were also heard around the world.

The site of Revere’s capture outside of Lexington, Massachusetts, from which point Samuel Prescott continued Revere’s route to Concord, Massachusetts

A silver tea and coffee service created by Paul Revere—commissioned by Dr. William Paine of Worcester for his bride, Lois Orne in 1773—is one of the highest achievements in design and craftsmanship credited to any eighteenth-century New England silversmith

For further study, read Paul Revere’s Ride by David Hackett Fischer, Oxford University, 1994.

Image Credits: 1 Paul Revere (wikipedia.org) 2 “Paul Revere’s Ride” Poem (wikipedia.org) 3 Rousing a village (wikipedia.org) 4 Hancock-Clarke House (wikipedia.org) 5 Paul Revere’s home (wikipedia.org) 6 Signal lantern (wikipedia.org) 7 Old North Church & Revere Statue (wikipedia.org) 8 Ride routes (wikipedia.org) 9 Site of Revere’s capture (wikipedia.org) 10 Revere silver service (wikipedia.org)